June 23, 2016

In the 1970s, economist Arthur Okun coined the term “misery index.” The misery index was meant to calculate the amount of economic misery by adding the unemployment rate to the annual inflation rate. This treats a one percentage-point rise in the unemployment rate as being no worse than a one percentage rise in the inflation rate.

In a sense, the Federal Reserve actually adheres to a version of Okun’s misery index when setting monetary policy. As part of its dual mandate, the Fed pursues the twin goals of “maximum employment” and “stable prices.” While the mandate allows room for ambiguity, many Fed officials seem to assign greater importance to inflation than unemployment.

However, as Binyamin Appelbaum reported three years ago in The New York Times, consumer surveys from both the U.S. and Europe indicate that unemployment creates about four times as much misery as inflation. This result has been attested to in a host of academic studies (see pages 1–3).

A properly constructed misery index would therefore place four times as much weight on a one percentage point rise in the unemployment rate as on a one percentage point rise in the inflation rate. In terms of promoting well-being, an economy with low unemployment will usually beat an economy with low inflation.

This is especially important today given the debate about whether the Fed should raise interest rates. In general terms, an interest rate hike would raise unemployment (at least compared to a situation without a rate hike) while decreasing the risk of higher inflation. If the Fed were to keep interest rates low, job growth would be stronger but the probability of higher inflation would rise.

On the other hand, it is not clear that inflation will overshoot the Fed’s 2.0 percent target even if policymakers wait to raise rates. Therefore the Fed must weigh the question: to what degree are they willing to increase unemployment in order to decrease the possibility of higher inflation?

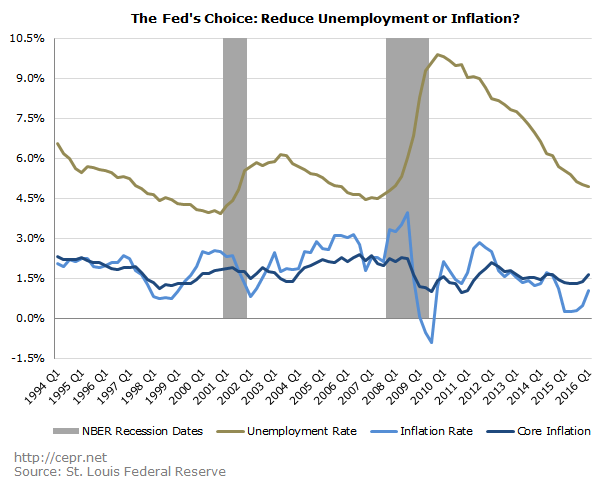

The figure below shows the unemployment rate and the inflation rate from 1994 to present. Also included is the “core” inflation rate, a measure which excludes volatile food and energy prices and is generally seen as a good predictor of future inflation. Today’s economy is experiencing low inflation and average unemployment. In the first quarter of 2016, unemployment was 4.9 percent (one-tenth of a percentage point lower than the average from 1994 to 2007), but inflation was 1.0 percent, far lower than the 1994–2007 average of 2.0 percent. The period of greatest well-being since 1970 (according to the properly constructed misery index) was from 1998 to 2000, when the unemployment rate averaged 4.2 percent and the inflation rate was 1.6 percent. If the Fed wants to reduce economic misery, it will tolerate the risk of slightly higher inflation in order to let the unemployment rate keep falling.