October 03, 2012

Journalists, pundits, politicians and the public will undoubtedly pay a lot of attention to the unemployment numbers that will be released this Friday. It’s important to understand whether the reasons for current unemployment are mainly structural — that worker’s skills or geographic location don’t match up to available jobs — or cyclical — that there just aren’t enough jobs out there.

CEPR, along with plenty of other economic experts, agree that no matter how you look it, current unemployment is mostly cyclical — there just isn’t enough demand in the economy. CEPR’s John Schmitt and Kris Warner explain why it’s so important to get this right:

The distinction between structural and cyclical unemployment has crucial implications for economic policy. If unemployment is “structural” then government policy that seeks to increase demand – low interest rates or fiscal stimulus, for example – will have little or no effect on the national unemployment rate and could even make matters worse by igniting inflation. If unemployment is “cyclical,” however, then expansionary macroeconomic policy can lower unemployment substantially with little or no risk of inflation.

Their detailed paper, “Deconstructing Structural Unemployment,” looks at 2 arguments for structural unemployment, and find little support for either:

The first argument is that if unemployment is structural, then there would be evidence that the large supply of unemployed construction workers lack the skills needed to find new jobs in other sectors of the economy. While construction workers have indeed suffered disproportionately in the downturn (due to the bursting of the housing bubble), it turns out that they have also been at least as successful in coping with the hostile labor market of recent years as workers displaced from other sectors. And construction workers’ skills are at least as well matched to the available jobs as workers displaced elsewhere in the economy.

The second argument is that falling house prices have reduced the mobility of unemployed workers — creating a “house lock” in which unemployed workers, who would otherwise relocate to regions with jobs, are stuck in high unemployment areas.The downturn in the housing market also appears to have had no measurable effect on the geographical mobility of displaced workers, but the economic effects are small, raising the pool of the unemployed by only a few percent (and the unemployment rate, by a much smaller amount).

Addressing more arguments for structural unemployment CEPR’s Dean Baker blogs:

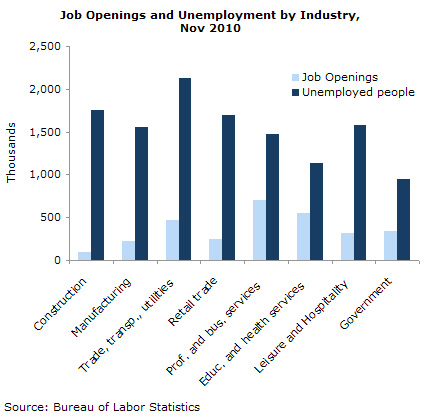

First, if there is a serious issue of structural unemployment then there should be some major sector(s) of the economy where the number of job openings outstrips the number of available workers. There is no major sector where the number of job openings is even half as large the number of unemployed workers from the industry.

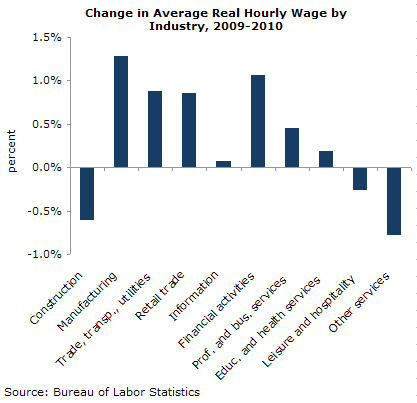

Second, if there is a serious issue of structural unemployment then the sectors that are having trouble finding workers should be bidding up wages. There is no sector that has a rate of real compensation growth that is even close to productivity growth or the 1.5 percent average over the years from 1996 to 2000.

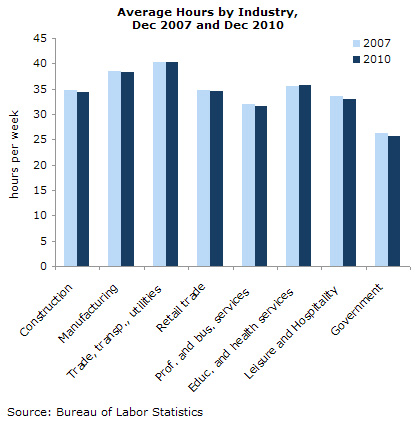

Third, if there is a serious issue of structural unemployment then employers would be working their existing workforce more hours because they are unable to find more workers to fill job openings. Only the financial industry reports average weekly hours that are higher today than at the onset of the recession. Even here the increase has been just 0.8 percent.

Fourth, if the current unemployment in the U.S. economy were structural then we should expect to see lower than normal rates for these college grads whose labor is in short supply. Instead, we see that their unemployment rate is more than twice the pre-recession level and close two and half times its 2000 level.

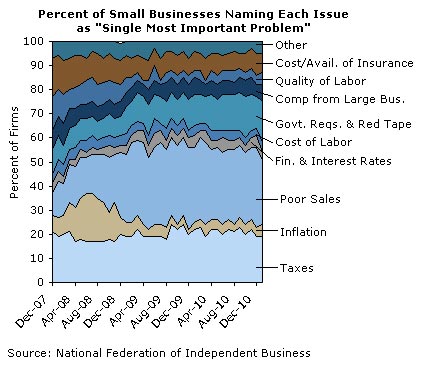

Dean also points out that “The evidence for the structural unemployment argument has mostly been anecdotal — interviews with managers who complained that they could not hire people at the wage they wanted to pay.” CEPR looked to the National Federation of Independent Businesses’ widely-cited survey of their own members and found that:

Since the recession began, respondents overwhelmingly have cited “poor sales,” suggesting that today’s unemployment is primarily due to a lack of demand. “Quality of labor,” the factor most consistent with structural unemployment, barely made the list.

And if you don’t believe CEPR, there are plenty of other experts that who’ve also thoroughly taken apart the structural unemployment myth. For example:

- Even Edward Lazear, who was chairman of George W. Bush’s Council of Economic Advisers, writes in the Wall Street Journal that “There is No ‘Structural’ Unemployment Problem.”

- The Economic Policy Institute’s work on this topic includes a commentary “Debunking the claim of structural unemployment” and a report on “Reasons for Skepticism About Structural Unemployment.”

- Nobel Laureate Paul Krugman regularly blogs on this topic, explaining why current unemployment is not structural.

- He includes some great work by Mike Konzcal at the Roosevelt Institute that knock down the structural unemployment myth.

As Dean Baker has explained again and again:

The real story of this downturn seems very simple. We had a huge housing bubble that was driving the economy through its effect on consumption and residential construction. When it collapsed, it created a gap in demand on the order of $1.2-$1.5 trillion. There is no easy way for private sector demand to fill this gap.

This means that we have to rely on government deficits to fill the demand gap in the short-term. In the longer term we should be looking to reducing the trade deficit. Residential construction should also help as it gradually returns to its trend levels from the extraordinarily depressed levels that resulted from the overbuilding of the bubble years.

Anyhow, the housing bubble story provides a simple answer as to why we are not creating jobs.