September 02, 2011

Matt Yglesias offers some “Cynical Thoughts on The Minimum Wage.” Cynical is fine, but informed would be better.

Most of the post focuses on what Yglesias believes are enforcement problems with the minimum wage. He recites an anecdote about a magazine that reclassified workers as interns rather than pay them the minimum wage; links to a series of exemptions to the federal minimum wage; and offers some hypothetical scenarios that might allow employers to sidestep the law.

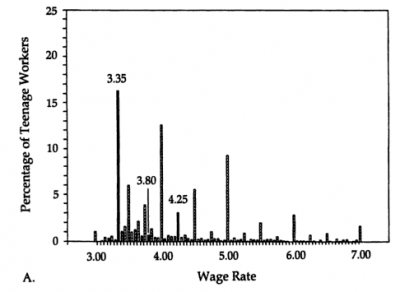

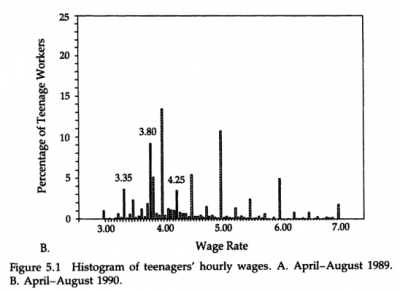

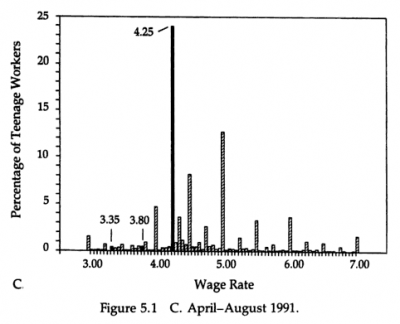

But, we actually have good empirical evidence on what happens after the minimum wage goes up. The series of three graphs below, taken from David Card and Alan Krueger’s landmark 1995 book on the minimum wage, are just one example.

Source: Card and Krueger, 1995.

Source: Card and Krueger, 1995.

Source: Card and Krueger, 1995.

As Card and Krueger explain:

These figures show the proportion of teenage workers whose wages fell within each 5-cent interval between $3.00 and 7.00 per hour, with the intervals containing $3.35, 3.80, and 4.25 per hour highlighted. The wage data pertain to the months of April through August of 1989, 1990, and 1991. During 1989, the minimum wage was $3.35 per hour, and, in Figure [A], a sizable spike in the wage distribution is apparent at $3.35. After the minimum wage increased to $3.80 per hour on April 1, 1990, the spike at $3.35 decreased, and a new spike arose at $3.80. The spike at $3.80 is especially significant in view of the fact that very few workers were paid $3.80 per hour prior to the increase in the minimum… Figure [C] shows that the spike in the wage distribution moved again, to $4.25 per hour in 1991, after the minimum wage was increased to that level on April 1, 1991.

The minimum wage may not be fully enforced, but the data demonstrate that the law does have an obvious and substantial impact on wages at the bottom.

None of this is to say that non-enforcement and evasion of labor law are not a problem. The National Employment Law Project, for example, has done excellent work documenting widespread violations –see, most recently, their report, “Broken Laws, Unprotected Workers” (pdf). But, as economist Arin Dube explains in the comments section to the Yglesias post, a helpful metaphor for thinking about this is the speed limit: “of course a lot of people drive above the speed limit. However, if the speed limit goes from 65 to 55, even offenders adjust their speed. Same thing is true for wage theft.”

Yglesias ends his post wondering whether another reason why the minimum wage might not have much impact on employment could be that employers “push low-skill workers into a greater mix of cash to non-cash forms of compensation.” This may happen, but both the non-enforcement issue and this compensation-mix argument accept the perfectly competitive labor-market model and try to make that simple model fit the inconvenient fact that the employment effects of moderate increases in the minimum wage seem to be pretty consistently close to zero.

The main driver of almost all of the “New Minimum Wage Research” since the early 1990s is the idea that the textbook model of the low-wage labor market is wrong, and wrong in ways that matter. What look to be small realities of the actual labor market –workers don’t have perfect information about jobs or hiring workers is costly, for instance– can end up making a big difference.

Just one example. Some firms pay their workers a bit above the going rate. As a result, they find it easier to recruit workers when they have a vacancy, and they also have fewer vacancies because workers stick around longer. In the standard perfectly competitive labor-market model, these “high road” firms would quickly go bankrupt. In more realistic models, such as the ones that motivate much of the new research on the minimum wage, the inclusion of real-world features such as turnover costs makes clear that higher wage costs might pay for themselves in other ways.

An important implication of these alternative models is that equally profitable “high road” and “low road” firms can exist side-by-side in the same labor market. From an economic point of view, both work. From a social point of view, however, the “high road” firms works better. In this light, the minimum wage “nudges” firms (well, more likely, drags them kicking and screaming) from one profitable way of doing business to another.

And to be clear about one final point. Nothing in these alternative models suggests that we could raise the minimum wage indefinitely without any impact on employment. What the theory and the empirical research suggest is that increases in the minimum wage in the range of our historical experience in the United States have not been associated with any significant employment losses. Note that even after the 2007-2009 increases in the minimum wage, we are still well below the historical level of the minimum-wage, in inflation-adjusted terms or as a share of the average wage.

This post originally appeared on John Schmitt’s blog, No Apparent Motive.