October 20, 2012

In his latest blogpost Paul Krugman makes the point that the recoveries from financial crises have in general been slow and difficult, but that they need not be. The point is that this downturn is not like the severe downturns in the 74-75 or 81-82, because they were both driven by the Fed raising interest rates to combat inflation. That left the obvious corrective step of lowering interest rates, which in both cases prompted a swift recovery.

That option does not exist today because this downturn was brought about a collapsed housing bubble, not the Fed raising interest rates. Okay, I just gave my addendum to the Krugman story. Yes, we did have a financial crisis in the fall of 2008. This crisis did hasten the pace of the downturn, but it was and is not the story of the recession. We would be in pretty much the same place today even if the financial crisis had not happened.

It is difficult to see any obvious way in which the current state of the financial system is seriously impeding recovery at this point. Unlike Japan, mid and large size firms in the United States have direct access to capital markets and are now able to borrow at record low interest rates. While some potential homebuyers are finding it more difficult to get mortgages than in the mid-90s (that’s the relevant comparison, not the nuttiness of the bubble years), the impact of restoring 90s era credit conditions for homeowners on the housing market would be trivial, especially if it went with mid-90s interest rates. In short, the problems of the economy are not directly related to the financial crisis.

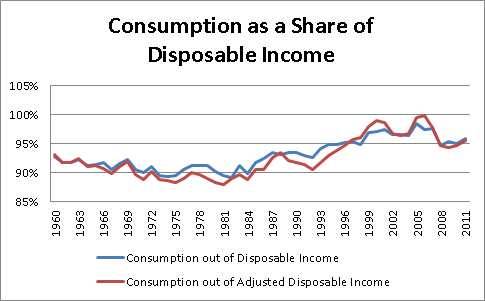

Nor are they directly related to indebtedness. The ratio of current consumption to disposable income is still high by historical standards, not low. While the consumption share of disposable income is not at the peak of the stock bubble of the housing bubble, when the saving rate was near zero, it remains far above the average for the 60s, 70s, the 80s or even the 90s. There is simply no reason to expect consumption to return to bubble levels when the bubble wealth that drove it has disappeared.

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis.

This gets to the more fundamental story of a recession driven by a collapsed housing bubble. We were able to reach near full employment at the peak of the bubble as a result of demand created by an extraordinary construction boom and consumption boom. The overbuilding of the bubble years led housing construction to fall well below trend levels. With the excess supply now being eroded by a growing population, housing construction will return to trend levels, but not the levels of the bubble years. This leaves a gap in demand of roughly 2 percentage points of GDP or $300 billion.

Consumption has already returned to a reasonable, if not excessive, share of disposable income. Are most households saving enough for retirement? The answer is almost certainly not, especially given the stated desire of the leadership of both parties to cut Social Security and Medicare benefits. This means that we have zero reason for expecting the consumption share of disposable income to go still higher, absent the return of another bubble.

The difference between a saving rate of 5 percent of disposable income and 0 is $500 billion in annual demand. Added to the $300 billion of missing demand from the residential construction sector, we need $800 billion or 5.4 percentage points of GDP, in additional demand from other sectors of the economy.

While the Romney crew might sing the praises of the job creators, only in Republican fantasy land could this demand possibly come from investment. There continues to be substantial excess supply in most categories of non-residential real estate, which leaves investment in equipment and software as the only source for additional demand any time soon. This sector of the economy has averaged less than 8 percent of GDP through the last four decades. It would take a real wild investment boom to see this share rise enough to fill the gap created by the collapse of the bubble, especially considering the large amounts of excess capacity in many sectors of the economy.

This leaves government and net exports. That is why those of us who believe in national income accounting and arithmetic praise the budget deficits every day of the week. In the short-term there is no alternative way to drive demand. The folks pushing for lower budget deficits are calling for less growth and more unemployment.

In the longer term we will need more net exports, which will only be brought about by a lower dollar. The trade agreement story pushed by both President Obama and Governor Romney is just silliness for children and economic reporters. These deals will not reduce the trade deficit and quite likely will increase it.

Anyhow, that is the quick story on the recession. My difference with Krugman is that it is the story of a collapsed bubble, not a financial crisis. (I recall in 2009 hearing folks like Stiglitz praise the well-regulated Spanish financial system and how this had allowed Spain to avoid a financial crisis. Well, maybe that wasn’t quite right.) Furthermore, deleveraging will not get us back to full employment. We will need more fiscal stimulus or a lower dollar. Alternatively, we can go the German route of using work sharing to sustain full employment even in an economy that is operating below its potential.

Comments