October 14, 2022

There was not much positive news in the September CPI report that came out yesterday. So, since I don’t have anything good to say on inflation, let’s change the topic to health care. (Actually, there is some basis for optimism on inflation, which I will get to in the next couple of days.)

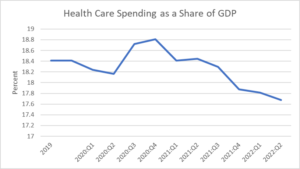

Anyhow, apart from the issues with inflation, there is an important story with health care that has gotten little attention. Health care spending has slowed sharply from its pre-pandemic path. In fact, measured as a share of GDP it was actually lower in the second quarter of 2022 than in 2019, as shown below.[1]

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis and author’s calculations, see text.

By my calculations, health care spending as share of GDP was 0.7 percent of GDP less in the second quarter of 2022 than it had been in 2019. This is especially impressive because the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) had projected that the health care spending share of GDP would rise by roughly 0.2 percentage points a year. That puts current spending roughly 1.3 percentage points below what CMS had projected before the pandemic.

This is a big deal. This falloff in spending corresponds to $325 billion annually in the current economy. That comes to roughly $1,000 a year per person, or $4,000 for a family of four, that is freed up for other purposes.

Of course, not all this money will show up in family budgets. Some of this is savings to the government on health care programs like Medicare and Medicaid. Some of this will be savings to employers, who presumably are paying somewhat less to insure their workers than they would have if health care spending had followed its projected path. But, some of this translates into savings to households who are paying less for medical services and insurance than would have been the case if health care costs had stayed on its pre-pandemic course.

It is important to recognize that the savings on health care is not all a positive story. One major source of savings is the million plus people who have died from COVID-19. The people who died from COVID-19 were on average older and less healthy than the population as a whole, and therefore likely received more medical care than most people. Their deaths meant less demand for medical services, but this is not how we want to save money.

It may also be the case that people are still getting fewer services than they might have before the pandemic. For example, spending on visits to dentists fell sharply during the pandemic for obvious reasons, but it seems to be largely on track at present.

There may be some efficiencies in the provision of services, which allow people to get the same quality care at a lower cost. For example, the use of telemedicine has exploded since the pandemic. A survey conducted by the Department of Health and Human Services found that one-in-four people reported having a remote visit with a health care provider in the prior four weeks. Since most people will not visit any health care provider in a random four-week period, this figure indicates that a very large share of the people needing health care are now taking advantage of remote visits. Home therapeutic devices may also substitute for visits to doctors or other health care professionals.

There is a possibility that these substitutions are jeopardizing the quality of care. We will only find this out after more time, if we discover a deterioration in health status. But, it is important to remember that what we value is health, not visits to the doctor or various medical tests and procedures. If we can have fewer services, and not have a deterioration in the public’s health, that is a positive for society.

This is not the first time that a sharp slowing in health care spending has passed unnoticed. The growth of health care spending slowed sharply after the passage of “Obamacare” in 2010. In 2009, the CMS projected that in 2019 we would spend $4.5 trillion, or 19.3 percent of GDP, on health care. In fact, we spent $3.8 trillion, or 17.7 percent of GDP, on health care in 2019. The difference of 1.6 percent of GDP is almost half of the military budget.

For some reason, the Democrats never took credit for this slowing in health care cost growth. While Obamacare surely was not the only factor leading to slower spending growth, it almost certainly played a role. And, there is no doubt that if spending growth had accelerated, even for reasons that had nothing to do with Obamacare, the Republicans and the media would have hyped this fact endlessly.

Anyhow, the reduction in the share of GDP going to health care spending since the start of the pandemic is a big deal. It deserves more attention than it has received.

[1] I know these numbers are slightly higher than what the CMS report for health care spending as a share of GDP. I assume this is due to some double counting, where I may have some government health care spending, which also shows up as consumption. For those wanting to check, I added lines 64, 119, 170, and 273 from NIPA Table 2.4.5U and line 32 from NIPA Table 3.12U. These are therapeutic equipment, pharmaceuticals and other medical products, health care services, and net health care insurance. Line 32 is the government spending on Medicaid and other health care provision. While my sum for this spending is obviously somewhat higher than the share CMS shows, which was 17.6 percent of GDP for 2019, presumably the changes since 2019 are following medical spending as defined by CMS reasonably closely.

Comments