Michelle Cottle had a NYT column headlined “What Voters Want That Trump Seems to Have.” She needed to make up a few facts to push her case. For example, she tells us that people don’t like Biden because crime is high. But, crime rose sharply in 2020 when Donald Trump was in the White House, it has fallen since Biden took office.

If people are actually unhappy about crime then they should be voting for Biden, not Trump. If they prefer Trump on this issue it is because they are confused about the timing of recent patterns in crime, perhaps because people like Ms. Cottle have been misleading them.

There is a similar story with Cottle’s pronouncements on inflation. She told readers that in the last year of Trump’s term, just before the pandemic:

“Inflation was practically nonexistent.”

That’s actually not what our friends at the Bureau of Labor Statistics say. Year-over-year inflation was 2.5 percent as of January of 2020, just before the pandemic hit.

That isn’t exactly frightening, but hardly nonexistent. In fact, with lower rental inflation pretty much baked into the data (we know this from patterns in housing units that turn over), the inflation rate is likely to be lower than this by Election Day.

Cottle also has advice for those of us who try to connect how people feel about the economy to economic data.

“The degree to which Mr. Biden’s policies have helped or hurt does not much matter, especially on the economy. He owns it. And here’s the thing: You can’t argue with voters’ feelings. Even if you win the debate on points, you’re not going to convince people that they or the nation is actually doing swell. Trying, in fact, often just makes you look like a condescending, out-of-touch jerk.”

This is true, people feel how they feel. We can ask why they feel the way they do (I suspect endless trashing of the economy in often dishonest ways by the media has a lot to do with it), but we can’t tell them how they should feel.

So, we can point out that real wages for many workers, especially those at the bottom, have risen in spite of the massive hit from the pandemic. We can point out that homeownership rates for young people, Blacks, Hispanics, and moderate-income homeowners have all risen under Biden. But yeah, people still feel how they feel.

However, we may want to look more broadly when asserting how people feel. According to the Conference Board, people report a higher level of workplace satisfaction currently than at any point in the nearly forty years that they have done their survey.

I don’t think it takes a huge amount of economic training to believe that workplace satisfaction has something to do with the economy. The workplace is where workers spend close to half of their waking hours, so if workers say they are more satisfied now than ever before, that seems like a really good story about the economy

But, I guess that New York Times columnists get to be condescending, out-of-touch jerks when they want to make their case. If they insist that people think the economy is awful, we can’t let what people say get in the way.

Michelle Cottle had a NYT column headlined “What Voters Want That Trump Seems to Have.” She needed to make up a few facts to push her case. For example, she tells us that people don’t like Biden because crime is high. But, crime rose sharply in 2020 when Donald Trump was in the White House, it has fallen since Biden took office.

If people are actually unhappy about crime then they should be voting for Biden, not Trump. If they prefer Trump on this issue it is because they are confused about the timing of recent patterns in crime, perhaps because people like Ms. Cottle have been misleading them.

There is a similar story with Cottle’s pronouncements on inflation. She told readers that in the last year of Trump’s term, just before the pandemic:

“Inflation was practically nonexistent.”

That’s actually not what our friends at the Bureau of Labor Statistics say. Year-over-year inflation was 2.5 percent as of January of 2020, just before the pandemic hit.

That isn’t exactly frightening, but hardly nonexistent. In fact, with lower rental inflation pretty much baked into the data (we know this from patterns in housing units that turn over), the inflation rate is likely to be lower than this by Election Day.

Cottle also has advice for those of us who try to connect how people feel about the economy to economic data.

“The degree to which Mr. Biden’s policies have helped or hurt does not much matter, especially on the economy. He owns it. And here’s the thing: You can’t argue with voters’ feelings. Even if you win the debate on points, you’re not going to convince people that they or the nation is actually doing swell. Trying, in fact, often just makes you look like a condescending, out-of-touch jerk.”

This is true, people feel how they feel. We can ask why they feel the way they do (I suspect endless trashing of the economy in often dishonest ways by the media has a lot to do with it), but we can’t tell them how they should feel.

So, we can point out that real wages for many workers, especially those at the bottom, have risen in spite of the massive hit from the pandemic. We can point out that homeownership rates for young people, Blacks, Hispanics, and moderate-income homeowners have all risen under Biden. But yeah, people still feel how they feel.

However, we may want to look more broadly when asserting how people feel. According to the Conference Board, people report a higher level of workplace satisfaction currently than at any point in the nearly forty years that they have done their survey.

I don’t think it takes a huge amount of economic training to believe that workplace satisfaction has something to do with the economy. The workplace is where workers spend close to half of their waking hours, so if workers say they are more satisfied now than ever before, that seems like a really good story about the economy

But, I guess that New York Times columnists get to be condescending, out-of-touch jerks when they want to make their case. If they insist that people think the economy is awful, we can’t let what people say get in the way.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The Republican Party, which now likes to call itself the party of working people, is demanding that President Biden agree to give the rich a license to steal and make life more difficult for ordinary workers. That may sound like a caricature, but unfortunately it isn’t.

Now that the Republicans finally have a Speaker, and the House of Representatives can go back to work, they immediately set about carrying through with their priorities. Top on this list is cutting funding for the I.R.S. so that it will not have the resources needed to go after rich tax cheats.

The Republicans apparently believe that rich people should not have to pay taxes if they don’t want to. And, many of them don’t. The government loses hundreds of billions of dollars a year in revenue because rich people get away with not paying the taxes they owe.

The Biden administration included a provision in the Inflation Reduction Act that increased funding for the I.R.S. so that it would be better able to catch people who are cheating on their taxes. The Republicans decided to make rescinding this funding a top priority by attaching it to a supplemental aid bill for Israel that has wide support in Congress.

The Republicans are claiming that reducing the I.R.S. funding will cover the cost of the funding for Israel. But this is beyond absurd. It would be like a store reducing its security against shoplifting in order to increase its profits.

Even a Republican politician understands that stores will not have higher profits if they don’t have any security against shoplifting. And, they know that we will collect less tax revenue if we don’t have anyone at the I.R.S. to ensure that rich people pay their taxes.

And, we have to be clear that this is about rich people paying their taxes. Most of us have the bulk of our taxes deducted directly from our paychecks. Not paying taxes is not an option for ordinary workers. It is only rich people, who have large amounts of income from selling stock, dividends, and business income that are able to evade paying the taxes they owe.

That may sound bad, but it gets worse. The Biden administration has instructed the I.R.S. to develop a system that would allow people to file their taxes for free using simple software available directly from I.R.S. This would save ordinary taxpayers billions of dollars a year that they now spend on tax filing services like H&R Block and Quicken.

That is exactly why the Republicans have made eliminating the Biden administration’s direct file option a top target. They included this provision in a House bill for funding a wide range of government functions. They apparently want to make sure that the money keeps going into the pockets of the tax filing services rather than staying in the pockets of ordinary workers.

It’s good that the Republicans keep telling us that they are the party of working people. Since their main priorities seem to be giving ever more money to the rich, and making life more difficult for ordinary workers, the rest of us would probably never know that they are the party of working people if they didn’t tell us.

The Republican Party, which now likes to call itself the party of working people, is demanding that President Biden agree to give the rich a license to steal and make life more difficult for ordinary workers. That may sound like a caricature, but unfortunately it isn’t.

Now that the Republicans finally have a Speaker, and the House of Representatives can go back to work, they immediately set about carrying through with their priorities. Top on this list is cutting funding for the I.R.S. so that it will not have the resources needed to go after rich tax cheats.

The Republicans apparently believe that rich people should not have to pay taxes if they don’t want to. And, many of them don’t. The government loses hundreds of billions of dollars a year in revenue because rich people get away with not paying the taxes they owe.

The Biden administration included a provision in the Inflation Reduction Act that increased funding for the I.R.S. so that it would be better able to catch people who are cheating on their taxes. The Republicans decided to make rescinding this funding a top priority by attaching it to a supplemental aid bill for Israel that has wide support in Congress.

The Republicans are claiming that reducing the I.R.S. funding will cover the cost of the funding for Israel. But this is beyond absurd. It would be like a store reducing its security against shoplifting in order to increase its profits.

Even a Republican politician understands that stores will not have higher profits if they don’t have any security against shoplifting. And, they know that we will collect less tax revenue if we don’t have anyone at the I.R.S. to ensure that rich people pay their taxes.

And, we have to be clear that this is about rich people paying their taxes. Most of us have the bulk of our taxes deducted directly from our paychecks. Not paying taxes is not an option for ordinary workers. It is only rich people, who have large amounts of income from selling stock, dividends, and business income that are able to evade paying the taxes they owe.

That may sound bad, but it gets worse. The Biden administration has instructed the I.R.S. to develop a system that would allow people to file their taxes for free using simple software available directly from I.R.S. This would save ordinary taxpayers billions of dollars a year that they now spend on tax filing services like H&R Block and Quicken.

That is exactly why the Republicans have made eliminating the Biden administration’s direct file option a top target. They included this provision in a House bill for funding a wide range of government functions. They apparently want to make sure that the money keeps going into the pockets of the tax filing services rather than staying in the pockets of ordinary workers.

It’s good that the Republicans keep telling us that they are the party of working people. Since their main priorities seem to be giving ever more money to the rich, and making life more difficult for ordinary workers, the rest of us would probably never know that they are the party of working people if they didn’t tell us.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

We all know about Donald Trump’s “Big Lie” that he won the 2020 election. This is of course laughable, there is nothing in the real world to support Trump’s fantasies of massive voter fraud.

However, there is arguably an even bigger lie that enjoys near universal acceptance in intellectual circles. It is the claim the huge rise in inequality over the last half century was due to market forces.

The usually insightful Peter Coy plays along with this Big Lie in his New York Times column today. Coy lays out the argument of a new NBER paper, by Ilyana Kuziemko, Nicolas Longuet Marx, and Suresh Naidu, that the Democrats have been hurt politically because they adopted a strategy, beginning in the seventies, of compensating losers from market outcomes.

The model of this story is that removing protectionist barriers in a movement towards free trade invariably creates winners and losers. According to standard theory, the winners are supposed to get more than the losers lose, so in principle we can tax the winners and pay the losers and make everyone better off.

The paper argues that this strategy is a political loser because people don’t want to see themselves as beneficiaries of government handouts. It’s also the case that there were never any serious proposals to tax the winners within an order of magnitude of what would be needed to compensate the losers.

However, the more important point, ignored by Coy, is that how we chose to move to “free trade” was itself a political choice. We could have moved to free trade by radically reducing the barriers that prevent doctors and dentists trained in India and other developing countries (or even rich countries) from practicing medicine in the United States. This could have still involved meeting U.S. standards, but medical students could train and test in other countries rather than the United States.

If we had gone this route, our doctors and dentists would likely be paid more in line with what they get in other rich countries, (e.g. around $150,000 a year rather than $350,000 a year) saving us close to $200 billion a year in health care expenses ($1,600 a family). We could have aggressively applied the quest for free trade to all highly paid professions, making highly paid professionals losers and blue collar workers winners.

The same story applies to patent and copyright monopolies. We have made these government-granted monopolies longer and stronger in the last half-century. Our elites have turned language and logic on its head and called these protections “free-trade.” They redistribute massive amounts of income upward, more than $400 billion a year ($3,200 per family) in the case of prescription drugs alone. Democrats have been fully complicit in making these protections longer and stronger, having supported the Bayh-Dole Act (approved under Carter) and a variety of other measures that meant greater protection both domestically and internationally.

In short, the issue is not just that the Democrats have supported a regime where the winners are supposed to compensate the losers from a “free market.” They have supported structuring the free market in ways that make the working-class losers. (Yes, this is my book, Rigged [it’s free.])

This means the working-class has very good reasons for not liking the modern Democratic Party, even if the Republicans are no better on this score. But, they won’t let you make these points in the New York Times, it hits too close to home.

We all know about Donald Trump’s “Big Lie” that he won the 2020 election. This is of course laughable, there is nothing in the real world to support Trump’s fantasies of massive voter fraud.

However, there is arguably an even bigger lie that enjoys near universal acceptance in intellectual circles. It is the claim the huge rise in inequality over the last half century was due to market forces.

The usually insightful Peter Coy plays along with this Big Lie in his New York Times column today. Coy lays out the argument of a new NBER paper, by Ilyana Kuziemko, Nicolas Longuet Marx, and Suresh Naidu, that the Democrats have been hurt politically because they adopted a strategy, beginning in the seventies, of compensating losers from market outcomes.

The model of this story is that removing protectionist barriers in a movement towards free trade invariably creates winners and losers. According to standard theory, the winners are supposed to get more than the losers lose, so in principle we can tax the winners and pay the losers and make everyone better off.

The paper argues that this strategy is a political loser because people don’t want to see themselves as beneficiaries of government handouts. It’s also the case that there were never any serious proposals to tax the winners within an order of magnitude of what would be needed to compensate the losers.

However, the more important point, ignored by Coy, is that how we chose to move to “free trade” was itself a political choice. We could have moved to free trade by radically reducing the barriers that prevent doctors and dentists trained in India and other developing countries (or even rich countries) from practicing medicine in the United States. This could have still involved meeting U.S. standards, but medical students could train and test in other countries rather than the United States.

If we had gone this route, our doctors and dentists would likely be paid more in line with what they get in other rich countries, (e.g. around $150,000 a year rather than $350,000 a year) saving us close to $200 billion a year in health care expenses ($1,600 a family). We could have aggressively applied the quest for free trade to all highly paid professions, making highly paid professionals losers and blue collar workers winners.

The same story applies to patent and copyright monopolies. We have made these government-granted monopolies longer and stronger in the last half-century. Our elites have turned language and logic on its head and called these protections “free-trade.” They redistribute massive amounts of income upward, more than $400 billion a year ($3,200 per family) in the case of prescription drugs alone. Democrats have been fully complicit in making these protections longer and stronger, having supported the Bayh-Dole Act (approved under Carter) and a variety of other measures that meant greater protection both domestically and internationally.

In short, the issue is not just that the Democrats have supported a regime where the winners are supposed to compensate the losers from a “free market.” They have supported structuring the free market in ways that make the working-class losers. (Yes, this is my book, Rigged [it’s free.])

This means the working-class has very good reasons for not liking the modern Democratic Party, even if the Republicans are no better on this score. But, they won’t let you make these points in the New York Times, it hits too close to home.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The New York Times seems to really love telling readers that China is facing a demographic crisis because its population is falling. It is not clear why the NYT thinks this amounts to a crisis for China, since many other countries have declining populations without experiencing any obvious crisis.

The most obvious examples are two of China’s neighbors, Japan and Korea, both of which are seeing modest drops in population. In both countries, per capita income is continuing to rise, in spite of a shrinking workforce. In fact, in South Korea, per capita income has risen at a 2.0 percent annual rate in the last four years, a faster pace than in the United States.

This growth figure actually understates improvements in living standards, since a smaller population also means less congestion and less pollution, factors that are not picked up in GDP. It is not clear why China should be worried if it experiences a similar decline in population.

The New York Times seems to really love telling readers that China is facing a demographic crisis because its population is falling. It is not clear why the NYT thinks this amounts to a crisis for China, since many other countries have declining populations without experiencing any obvious crisis.

The most obvious examples are two of China’s neighbors, Japan and Korea, both of which are seeing modest drops in population. In both countries, per capita income is continuing to rise, in spite of a shrinking workforce. In fact, in South Korea, per capita income has risen at a 2.0 percent annual rate in the last four years, a faster pace than in the United States.

This growth figure actually understates improvements in living standards, since a smaller population also means less congestion and less pollution, factors that are not picked up in GDP. It is not clear why China should be worried if it experiences a similar decline in population.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Understanding the economy is often like putting together a jigsaw puzzle. You try to put together the pieces in a way where they fit together and give a clear picture. Unfortunately, the data do not always cooperate with this effort.

That is very much the case with the October jobs report released yesterday. On the one hand, we can look to the 150,000 job growth reported in the establishment survey and say that we had another month of very solid, albeit slowing, job growth. The figure is especially impressive when we add in the roughly 30,000 workers who were not counted because of the UAW strike. These workers will show up in the November data, now that the strike has ended.

However, we get a very different picture from the household survey. This showed another 0.1 percentage point rise in the unemployment rate to 3.9 percent. While this is still very low by historical measures, it is an increase of 0.5 percentage points from the April level. Furthermore, the household survey showed an actual drop in employment, with the number of people reporting that they are employed down by 348,000 from the September level.

This divergence continues a pattern since April. Over the last six months, the establishment survey showed a gain of 1,234,000 jobs. The household survey showed an increase in the number of people employed of just 191,000.

The two surveys are often out-of-line, that has been especially the case in the pandemic recovery. Many of us were very troubled by the discrepancy that was reported last year. In the eleven months from January 2022 to December, 2022 the establishment survey showed the economy created 4,430,000 jobs. The household survey showed employment had increased by just 2,120,000, creating a gap of more than 2,300,000 jobs.

This gap was hugely reduced when the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) introduced new population controls in January, based on Census data, which added 954,000 to the employment figure. Job growth in the establishment survey was also revised down by around 300,000 in the annual benchmarking to state unemployment insurance filings. That still left a substantial gap, but considerably less than had previously been reported. (Some of this gap is due to differences in definitions. There was a fall in self-employment in 2022. This would lower employment in the household survey, but it would not show up in the establishment data.)

When the surveys do diverge, to my view it is always better to go with the establishment survey. It has a much larger sample and far higher response rate. It surveys 651,000 establishments every month. By contrast the household survey only covers 60,000 households.

The response rate to the household survey has fallen sharply over the last three decades and it is now just over 70 percent. This raises serious issues of non-response bias, since there is reason to believe that people who are not employed are less likely to respond to the survey.

The response rate to the establishment survey has also fallen somewhat. The advance report, which is the basis for the employment report for the month, only has a response rate around 65 percent. However, BLS continues to collect responses for two subsequent months. The response rate by the third month is over 93 percent. Given its size and high response rate, at least by the third month, the establishment survey should be a much more reliable gage of the labor market.

We can also look to try to reconcile what we see in these surveys with other data on the economy. We saw truly extraordinary productivity growth in the second and third quarters, 3.6 percent and 4.7 percent, respectively. The productivity data are highly erratic, and also subject to large revisions, but it is definitional that if employment grew less than reported in the establishment survey, productivity growth would have been even higher than reported.

We also have other labor market surveys, notably the Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey (JOLTS). This survey measures job openings listed by companies, as well as hiring, firing, and quits. The JOLTS data have shown some weakening over the last nine months, but this is consistent with the sort of slowing in job growth we have seen in the establishment data. It is not consistent with the virtual halting of employment growth implied by the household data. Private measures, like the Indeed data on new hires and listings, is also consistent with gradual slowing in a still strong labor market, rather than the grim story in the household data.

The household survey also regularly gives us anomalies that clearly did not actually happen in the economy. In the October report, the data on employment rates for college educated workers implied that the number of college-educate people in the country increased by 1.1 million from September to October.[1] The Biden administration has tried to push policies that will make it easier for people to go to college, but I doubt that it will be taking credit for this one-month jump in the number of college grads.

What Does the Establishment Survey Tell Us?

If we can largely dismiss the grim picture from the household survey, we then have to ask what does the establishment survey tell us about the state of the economy? It is generally a good story, but there are some grounds for concern.

The rate of employment growth is clearly slowing, but 180,000 new jobs is hardly cause for concern. The Fed had been raising interest rates with the goal of slowing the rate of job growth. The argument is that with unemployment below 4.0 percent, there are not very many people still looking to be employed, and the number of new entrants to the labor market is not over 200,000 a month. Therefore, if we had continued to see the rapid job growth of 2022 and the first half of 2023, we would see substantial upward pressure on wages, which would be inflationary.[2] From this standpoint, the slower rate of job growth is just what the Fed was looking for, and should be the basis for it easing up on interest rates, or at least not raising them further.

In this vein, the establishment data also showed that the rate of growth of the hourly wage has slowed sharply. The annual rate over the last three months is just 3.2 percent. With inflation slowing to rates below 3.0 percent, this will still allow for real wage growth, but should not cause concerns about inflationary pressure in the economy. Wage growth by this measure averaged 3.4 percent in 2018-2019, when inflation was at the Fed’s 2.0 percent target.

All of this looks very good from the standpoint of a sustainable recovery. Strong job growth, combined with modest growth in real wages, should allow for consumption growth to remain healthy. And, consumption is by far the largest component of GDP.

However, there is some basis for concern in the establishment survey. The job growth for October was heavily concentrated in a small number of sectors. Health care added 58,400 jobs, and the larger category health care and social assistance added 77,200 jobs, more than half of the employment growth reported for the month. (It’s still 43 percent of job growth if we adjust for the UAW strike.) The government sector, mostly state and local governments, added 51,000 jobs in October. This doesn’t leave much room for job growth in other sectors.

Retail, which accounts for almost 10.0 percent of payroll employment, added just 700 jobs. Restaurants, which have added an average of 31,000 jobs a month over the last year, lost 7,500 jobs in October. The transportation and warehousing sector, which is responsible for moving stuff around, lost 12,100 jobs, mostly in the category of warehousing and storage. And, the financial sector lost 2,000 jobs, driven by a drop in credit intermediation (e.g. mortgage issuance) of 10,000 jobs.

These are all somewhat worrying signs, since a recovery that is driven by a small number of sectors may not have long to live. In keeping with this concern, the one-month employment diffusion index, which measures the percentage of industries adding workers, fell from 61.4 in September to 52.0, the lowest level since the lockdowns. So, there is some ground for concern.

However, we can find some positives looking by industry. Construction, which is historically the most cyclically sensitive sector, along with manufacturing, added a healthy 23,000 jobs in October. And manufacturing employment would have been pretty much flat, had it not been for the impact of the UAW strike.

Also, the information sector lost 9,000 jobs in October, primarily due to a decline in employment of 5,400 in the motion picture industry. This is largely due to the ongoing strike by the Screen Actors Guild, which has caused most movie production to grind to a halt. Presumably this strike will end at some point and we will see a jump in employment in the sector.

Overall Picture: Things Look Good, but We Need to Worry

I suppose we should always be worried about the possibility of bad events on the horizon. For example, it is certainly possible to envision scenarios in which the wars in Ukraine and the Middle East expand in ways that have large economic impacts, in addition to an enormous human toll. High long-term interest rates have both put a huge cramp on the housing market (existing home sales are down more than 30 percent) and have created the basis for more of the financial instability that we saw with the collapse of Silicon Valley Bank. A Fed rate cut, or even a signal that one is on the horizon, could be a huge help here.

But for now, most aspects of the economy are looking pretty good. There have been few times in the last half-century where we could tell a better story about the state of the economy.

[1] The September data showed an employment-to-population ratio for college grads of 71.9 percent, with employment of 62,907,000. This implies a population of college grads of 87,492,000. The October data showed the employment-to-population ratio had fallen to 71.3 percent, but the number of employed college grads had increased to 63,172,000. That implies a total population of college grads of 88,600,000, a gain of more than 1.1 million from September.

[2] There are two arguments on wages and inflation that should be distinguished. One is that rapid wage growth caused the jump in inflation we saw in 2021 and 2022. This can be easily dismissed, since prices outpaced wages, at least through the first half of 2022. However, there is a second argument that needs to be taken seriously. If we sustain a rapid rate of wage growth going forward (wages had been growing at more than a 6.0 percent annual rate at the start of 2022), it will lead to inflation. Wages can outpace prices in line with productivity growth, and we can have some period where wages rise at the expense of profits, reversing some of the increase in the profit share since the pandemic and in prior years. However, wages cannot persistently outpace profits by an amount in excess of productivity growth, without leading to serious problems with inflation.

Understanding the economy is often like putting together a jigsaw puzzle. You try to put together the pieces in a way where they fit together and give a clear picture. Unfortunately, the data do not always cooperate with this effort.

That is very much the case with the October jobs report released yesterday. On the one hand, we can look to the 150,000 job growth reported in the establishment survey and say that we had another month of very solid, albeit slowing, job growth. The figure is especially impressive when we add in the roughly 30,000 workers who were not counted because of the UAW strike. These workers will show up in the November data, now that the strike has ended.

However, we get a very different picture from the household survey. This showed another 0.1 percentage point rise in the unemployment rate to 3.9 percent. While this is still very low by historical measures, it is an increase of 0.5 percentage points from the April level. Furthermore, the household survey showed an actual drop in employment, with the number of people reporting that they are employed down by 348,000 from the September level.

This divergence continues a pattern since April. Over the last six months, the establishment survey showed a gain of 1,234,000 jobs. The household survey showed an increase in the number of people employed of just 191,000.

The two surveys are often out-of-line, that has been especially the case in the pandemic recovery. Many of us were very troubled by the discrepancy that was reported last year. In the eleven months from January 2022 to December, 2022 the establishment survey showed the economy created 4,430,000 jobs. The household survey showed employment had increased by just 2,120,000, creating a gap of more than 2,300,000 jobs.

This gap was hugely reduced when the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) introduced new population controls in January, based on Census data, which added 954,000 to the employment figure. Job growth in the establishment survey was also revised down by around 300,000 in the annual benchmarking to state unemployment insurance filings. That still left a substantial gap, but considerably less than had previously been reported. (Some of this gap is due to differences in definitions. There was a fall in self-employment in 2022. This would lower employment in the household survey, but it would not show up in the establishment data.)

When the surveys do diverge, to my view it is always better to go with the establishment survey. It has a much larger sample and far higher response rate. It surveys 651,000 establishments every month. By contrast the household survey only covers 60,000 households.

The response rate to the household survey has fallen sharply over the last three decades and it is now just over 70 percent. This raises serious issues of non-response bias, since there is reason to believe that people who are not employed are less likely to respond to the survey.

The response rate to the establishment survey has also fallen somewhat. The advance report, which is the basis for the employment report for the month, only has a response rate around 65 percent. However, BLS continues to collect responses for two subsequent months. The response rate by the third month is over 93 percent. Given its size and high response rate, at least by the third month, the establishment survey should be a much more reliable gage of the labor market.

We can also look to try to reconcile what we see in these surveys with other data on the economy. We saw truly extraordinary productivity growth in the second and third quarters, 3.6 percent and 4.7 percent, respectively. The productivity data are highly erratic, and also subject to large revisions, but it is definitional that if employment grew less than reported in the establishment survey, productivity growth would have been even higher than reported.

We also have other labor market surveys, notably the Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey (JOLTS). This survey measures job openings listed by companies, as well as hiring, firing, and quits. The JOLTS data have shown some weakening over the last nine months, but this is consistent with the sort of slowing in job growth we have seen in the establishment data. It is not consistent with the virtual halting of employment growth implied by the household data. Private measures, like the Indeed data on new hires and listings, is also consistent with gradual slowing in a still strong labor market, rather than the grim story in the household data.

The household survey also regularly gives us anomalies that clearly did not actually happen in the economy. In the October report, the data on employment rates for college educated workers implied that the number of college-educate people in the country increased by 1.1 million from September to October.[1] The Biden administration has tried to push policies that will make it easier for people to go to college, but I doubt that it will be taking credit for this one-month jump in the number of college grads.

What Does the Establishment Survey Tell Us?

If we can largely dismiss the grim picture from the household survey, we then have to ask what does the establishment survey tell us about the state of the economy? It is generally a good story, but there are some grounds for concern.

The rate of employment growth is clearly slowing, but 180,000 new jobs is hardly cause for concern. The Fed had been raising interest rates with the goal of slowing the rate of job growth. The argument is that with unemployment below 4.0 percent, there are not very many people still looking to be employed, and the number of new entrants to the labor market is not over 200,000 a month. Therefore, if we had continued to see the rapid job growth of 2022 and the first half of 2023, we would see substantial upward pressure on wages, which would be inflationary.[2] From this standpoint, the slower rate of job growth is just what the Fed was looking for, and should be the basis for it easing up on interest rates, or at least not raising them further.

In this vein, the establishment data also showed that the rate of growth of the hourly wage has slowed sharply. The annual rate over the last three months is just 3.2 percent. With inflation slowing to rates below 3.0 percent, this will still allow for real wage growth, but should not cause concerns about inflationary pressure in the economy. Wage growth by this measure averaged 3.4 percent in 2018-2019, when inflation was at the Fed’s 2.0 percent target.

All of this looks very good from the standpoint of a sustainable recovery. Strong job growth, combined with modest growth in real wages, should allow for consumption growth to remain healthy. And, consumption is by far the largest component of GDP.

However, there is some basis for concern in the establishment survey. The job growth for October was heavily concentrated in a small number of sectors. Health care added 58,400 jobs, and the larger category health care and social assistance added 77,200 jobs, more than half of the employment growth reported for the month. (It’s still 43 percent of job growth if we adjust for the UAW strike.) The government sector, mostly state and local governments, added 51,000 jobs in October. This doesn’t leave much room for job growth in other sectors.

Retail, which accounts for almost 10.0 percent of payroll employment, added just 700 jobs. Restaurants, which have added an average of 31,000 jobs a month over the last year, lost 7,500 jobs in October. The transportation and warehousing sector, which is responsible for moving stuff around, lost 12,100 jobs, mostly in the category of warehousing and storage. And, the financial sector lost 2,000 jobs, driven by a drop in credit intermediation (e.g. mortgage issuance) of 10,000 jobs.

These are all somewhat worrying signs, since a recovery that is driven by a small number of sectors may not have long to live. In keeping with this concern, the one-month employment diffusion index, which measures the percentage of industries adding workers, fell from 61.4 in September to 52.0, the lowest level since the lockdowns. So, there is some ground for concern.

However, we can find some positives looking by industry. Construction, which is historically the most cyclically sensitive sector, along with manufacturing, added a healthy 23,000 jobs in October. And manufacturing employment would have been pretty much flat, had it not been for the impact of the UAW strike.

Also, the information sector lost 9,000 jobs in October, primarily due to a decline in employment of 5,400 in the motion picture industry. This is largely due to the ongoing strike by the Screen Actors Guild, which has caused most movie production to grind to a halt. Presumably this strike will end at some point and we will see a jump in employment in the sector.

Overall Picture: Things Look Good, but We Need to Worry

I suppose we should always be worried about the possibility of bad events on the horizon. For example, it is certainly possible to envision scenarios in which the wars in Ukraine and the Middle East expand in ways that have large economic impacts, in addition to an enormous human toll. High long-term interest rates have both put a huge cramp on the housing market (existing home sales are down more than 30 percent) and have created the basis for more of the financial instability that we saw with the collapse of Silicon Valley Bank. A Fed rate cut, or even a signal that one is on the horizon, could be a huge help here.

But for now, most aspects of the economy are looking pretty good. There have been few times in the last half-century where we could tell a better story about the state of the economy.

[1] The September data showed an employment-to-population ratio for college grads of 71.9 percent, with employment of 62,907,000. This implies a population of college grads of 87,492,000. The October data showed the employment-to-population ratio had fallen to 71.3 percent, but the number of employed college grads had increased to 63,172,000. That implies a total population of college grads of 88,600,000, a gain of more than 1.1 million from September.

[2] There are two arguments on wages and inflation that should be distinguished. One is that rapid wage growth caused the jump in inflation we saw in 2021 and 2022. This can be easily dismissed, since prices outpaced wages, at least through the first half of 2022. However, there is a second argument that needs to be taken seriously. If we sustain a rapid rate of wage growth going forward (wages had been growing at more than a 6.0 percent annual rate at the start of 2022), it will lead to inflation. Wages can outpace prices in line with productivity growth, and we can have some period where wages rise at the expense of profits, reversing some of the increase in the profit share since the pandemic and in prior years. However, wages cannot persistently outpace profits by an amount in excess of productivity growth, without leading to serious problems with inflation.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The New York Times ran a piece noting the huge increase in China’s use of solar power, but also highlighted concerns about its decision to build more coal-powered electricity plants. (The headline was “China Is Winning in Solar Power, but Its Coal Use Is Raising Alarm”) The piece talked about how John Kerry, President Biden’s special envoy for climate change, plans to raise the issue of coal with his Chinese counterpart at a meeting that starts Friday and that the issue is also likely to come up at a summit meeting with Biden and Xi next month.

While it is discouraging to see China continuing to build coal-powered plants, it is continuing to add wind and solar generation capacity at an incredibly fast pace. It is adding almost as much as the rest of the world combined, as this article notes.

The pace at which it adds capacity shows no evidence of slowing and may in fact accelerate if Xi decides to incorporate clean energy in a stimulus package. As a result of its rapid adoption of clean energy, its greenhouse gas emissions may peak next year, well ahead of its 2030 target. As it continues to add wind and solar capacity, its emissions will fall, especially in the context of its widely touted growth slowdown.

This raises the question of why it continues to build coal-powered plants. If China’s wind and solar capacity is growing more than its demand for electricity, this would imply less need for energy from coal-power plants, not more. And, once you have wind and solar capacity in place, it is far cheaper to get energy from these sources than from a coal-powered plant.

I can’t claim much knowledge of China’s politics, but I can see an analogous story in the United States. The Biden administration is pushing ahead with leasing large amounts of federal land for oil and gas development, even as it has put in place by far the most aggressive program for promoting clean energy the country has seen.

If the push for solar and wind energy is successful, there will be little demand for oil and gas from the land now being put up for lease. In that context, the leasing of land is an empty gesture to the oil and gas industry that will have little impact on future greenhouse gas emissions. (If it seems hard to imagine that major companies would put up tens of millions of dollars for leases that may never be used, consider that venture capitalists put up billions of dollars to finance We Work, a company whose great innovation was renting office space.)

If Xi faces comparable political considerations in China, it may make sense to allow politically connected interest groups to build coal-powered plants, even if there will be very little demand for their electricity once they are completed. Again, I have no way of knowing if Xi is making this sort of political calculation, but I do know that it is much cheaper to get electricity from wind and solar capacity that is already installed than from a coal-powered plant. Unless the plan is to subsidize the use of electricity from coal, most of these plants will never generate much electricity. From that standpoint, if China continues to aggressively add wind and solar capacity, we don’t really have to worry much about its construction of coal-powered plants.

The New York Times ran a piece noting the huge increase in China’s use of solar power, but also highlighted concerns about its decision to build more coal-powered electricity plants. (The headline was “China Is Winning in Solar Power, but Its Coal Use Is Raising Alarm”) The piece talked about how John Kerry, President Biden’s special envoy for climate change, plans to raise the issue of coal with his Chinese counterpart at a meeting that starts Friday and that the issue is also likely to come up at a summit meeting with Biden and Xi next month.

While it is discouraging to see China continuing to build coal-powered plants, it is continuing to add wind and solar generation capacity at an incredibly fast pace. It is adding almost as much as the rest of the world combined, as this article notes.

The pace at which it adds capacity shows no evidence of slowing and may in fact accelerate if Xi decides to incorporate clean energy in a stimulus package. As a result of its rapid adoption of clean energy, its greenhouse gas emissions may peak next year, well ahead of its 2030 target. As it continues to add wind and solar capacity, its emissions will fall, especially in the context of its widely touted growth slowdown.

This raises the question of why it continues to build coal-powered plants. If China’s wind and solar capacity is growing more than its demand for electricity, this would imply less need for energy from coal-power plants, not more. And, once you have wind and solar capacity in place, it is far cheaper to get energy from these sources than from a coal-powered plant.

I can’t claim much knowledge of China’s politics, but I can see an analogous story in the United States. The Biden administration is pushing ahead with leasing large amounts of federal land for oil and gas development, even as it has put in place by far the most aggressive program for promoting clean energy the country has seen.

If the push for solar and wind energy is successful, there will be little demand for oil and gas from the land now being put up for lease. In that context, the leasing of land is an empty gesture to the oil and gas industry that will have little impact on future greenhouse gas emissions. (If it seems hard to imagine that major companies would put up tens of millions of dollars for leases that may never be used, consider that venture capitalists put up billions of dollars to finance We Work, a company whose great innovation was renting office space.)

If Xi faces comparable political considerations in China, it may make sense to allow politically connected interest groups to build coal-powered plants, even if there will be very little demand for their electricity once they are completed. Again, I have no way of knowing if Xi is making this sort of political calculation, but I do know that it is much cheaper to get electricity from wind and solar capacity that is already installed than from a coal-powered plant. Unless the plan is to subsidize the use of electricity from coal, most of these plants will never generate much electricity. From that standpoint, if China continues to aggressively add wind and solar capacity, we don’t really have to worry much about its construction of coal-powered plants.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

I was sorry to hear that Ady Barkan died today. He was just 39 years old. He had ALS, a terrible disease that progresses gradually, impairing more and more of the body’s functions over time.

I first met Ady before he was diagnosed with the disease. He was a tireless and creative organizer. He led the Fed Up campaign, an effort to force the Federal Reserve Board to focus on full employment, and not just fighting inflation. Full employment is in fact a part of its legal mandate, in spite of what many economists might tell you.

Ady pushed the Fed to take the full employment part of its mandate seriously. He organized among community groups, labor unions, and others to press the case.

As research shows, full employment is not just a question of getting the overall unemployment rate down, it is an issue that disproportionately affects Blacks, Hispanics, the less-educated, people with criminal records, and others who face discrimination in the labor market. When the labor market is tight, employers have to hire those whomthey may not otherwise consider employing.

Not only does unemployment fall most for these disadvantaged groups in a tight labor market, a strong labor market also enables them to secure real wage gains. This is a story we have seen well-supported in the pandemic recovery.

Ady pressed this case with then Fed Chair, and current Treasury Secretary, Janet Yellen, who took the argument seriously and encouraged the members of the Fed’s policy setting Open Market Committee to meet with Fed Up. Yellen’s successor, the current Chair Jerome Powell, often sounded like he was reading from Fed Up’s hymn book when he touted the praises of low unemployment.

This shift in Fed policy towards promoting full employment, and not just obsessing about inflation, was a remarkable victory. It improved the lives of tens of millions of workers.

Unfortunately, Ady’s disease progressed and he had to cut back on his work. But he insisted on still trying to do what he could and took on a new cause, promoting national health care insurance, and in particular, Medicare for All.

Ady famously confronted Arizona Senator Jeff Flake on an airplane, and urged him to vote to keep Obamacare. Flake, a relatively moderate Republican, engaged politely, but ultimately could not be persuaded to vote against his party.

I had the privilege to testify alongside Ady on the first Congressional panel ever devoted to a discussion of Medicare for All. At that point, Ady was in a wheelchair and had to rely on a mechanical voice, since he could no longer speak without assistance.

Nonetheless, he made the case forcefully. The United States is a rich country. It can afford universal Medicare. The problem is it needs the political will.

It is a tragedy for the country, but obviously first and foremost for his family, that Ady’s disease continued to progress and has now taken his life. He had a tremendous amount to offer, and he has much to show, even in his short life.

My best wishes to his family and those close to him. This is a huge loss.

I was sorry to hear that Ady Barkan died today. He was just 39 years old. He had ALS, a terrible disease that progresses gradually, impairing more and more of the body’s functions over time.

I first met Ady before he was diagnosed with the disease. He was a tireless and creative organizer. He led the Fed Up campaign, an effort to force the Federal Reserve Board to focus on full employment, and not just fighting inflation. Full employment is in fact a part of its legal mandate, in spite of what many economists might tell you.

Ady pushed the Fed to take the full employment part of its mandate seriously. He organized among community groups, labor unions, and others to press the case.

As research shows, full employment is not just a question of getting the overall unemployment rate down, it is an issue that disproportionately affects Blacks, Hispanics, the less-educated, people with criminal records, and others who face discrimination in the labor market. When the labor market is tight, employers have to hire those whomthey may not otherwise consider employing.

Not only does unemployment fall most for these disadvantaged groups in a tight labor market, a strong labor market also enables them to secure real wage gains. This is a story we have seen well-supported in the pandemic recovery.

Ady pressed this case with then Fed Chair, and current Treasury Secretary, Janet Yellen, who took the argument seriously and encouraged the members of the Fed’s policy setting Open Market Committee to meet with Fed Up. Yellen’s successor, the current Chair Jerome Powell, often sounded like he was reading from Fed Up’s hymn book when he touted the praises of low unemployment.

This shift in Fed policy towards promoting full employment, and not just obsessing about inflation, was a remarkable victory. It improved the lives of tens of millions of workers.

Unfortunately, Ady’s disease progressed and he had to cut back on his work. But he insisted on still trying to do what he could and took on a new cause, promoting national health care insurance, and in particular, Medicare for All.

Ady famously confronted Arizona Senator Jeff Flake on an airplane, and urged him to vote to keep Obamacare. Flake, a relatively moderate Republican, engaged politely, but ultimately could not be persuaded to vote against his party.

I had the privilege to testify alongside Ady on the first Congressional panel ever devoted to a discussion of Medicare for All. At that point, Ady was in a wheelchair and had to rely on a mechanical voice, since he could no longer speak without assistance.

Nonetheless, he made the case forcefully. The United States is a rich country. It can afford universal Medicare. The problem is it needs the political will.

It is a tragedy for the country, but obviously first and foremost for his family, that Ady’s disease continued to progress and has now taken his life. He had a tremendous amount to offer, and he has much to show, even in his short life.

My best wishes to his family and those close to him. This is a huge loss.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Back in the 1990s, whining about the impending disaster from the retirement of baby boomer cohorts was all the rage. Private equity billionaire Peter Peterson’s polemics were big sellers, as very serious people struggled with how we could deal with this tidal wave of retirees. The basic story was that a rising ratio of retirees to workers would create a crushing burden for the younger people that were still in the labor force.

This argument went somewhat out of style over time. In part, the projection of exploding healthcare costs that drove the horror story turned out not to happen. Back in 2000, the long-term projections showed that healthcare would account for roughly one-third of total consumption spending by now. In fact, actual healthcare spending is less than 25.0 percent of total consumption. The difference between the 2000 projection and actual healthcare spending leaves about $1.5 trillion on the table (around $12k per family, each year) for us to spend on other things.

The second reason this demographic horror story went out of style was the slow recovery from the Great Recession. It took us over a decade to return to full employment following the collapse of the housing bubble. The problem for the economy in this decade was not that spending was too high, but rather that it was too low. (This is known as the “which way is up?” problem in economics.) If we had larger deficits during the last decade it would have provided a boost to growth and led to less unemployment.

Finally, the impending retirement of the baby boomers was no longer impending as they began to retire in the last decade. At the start of the decade the oldest baby boomers were already age 64. By 2020, the oldest baby boomers were age 74 and the youngest were already age 56. A substantial portion of the baby boom generation was already retired and the world had not ended.

The Return of the Demographic Crisis

But, as they say in Washington, no bad idea ever stays dead for long. In recent months the demographic crisis from retiring baby boomers seems to be everywhere. The major news outlets are filled with piece after piece telling us that we are running out of workers, at least when they are not telling us how the spread of robots and AI will create mass unemployment. (Yes, those claims are contradictory, but don’t tell any elite intellectual type.)

Anyhow, the basic story of the aging crisis is that workers will have to turn over a large portion of their paycheck to cover the costs of a growing population of retirees. This concern is supposed to lead us to cut Social Security and Medicare benefits and tell workers that they have to work later in life.

There are a couple of important points to be made at the start of any serious discussion. First, we have already raised the age at which people are eligible for full Social Security benefits. It had been 65 for people born before 1940. It has been gradually raised to 67 for people born after 1960. So, we have already taken account of people’s increased longevity in setting the parameters for Social Security.

The second point is that the gains in life expectancy have not been evenly shared. For people born in 1930 the gap in life expectancy, at age 50, between the top income quintile and the bottom income quintile for men was 5.0 years, and for women was 3.9 years. For the cohort born in 1960, the gap had increased to 12.7 years for men and 13.6 years for women. This means that almost all the gains in life expectancy over the last half century have been for those at the top of the income ladder. Those further down have seen little or no gains in life expectancy.

Next, it is important to have some idea of the dimensions of the aging “crisis.” We all know about the widely touted projected shortfalls in Social Security and Medicare. Let’s imagine that we made them up by raising the payroll tax. (That’s not the best way to deal with the problem, but this is just a hypothetical exercise.)

Suppose we raised the payroll tax by 4.0 percentage points tomorrow. Given current projections, this would be roughly enough to make the Social Security and Medicare trust funds solvent forever.

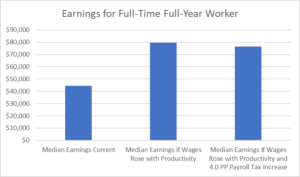

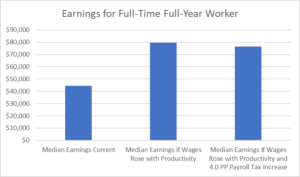

The graph below shows the current annual wage for a person getting the median wage, working full-time full year (50 weeks at 40 hours a week). It also shows what this worker would be getting if the median wage had kept pace with productivity growth, as it did in the long post-war boom from 1947 to 1973. And, it shows what this pay would have been if, in this scenario, we increased the payroll tax by 4.0 percentage points.[1]

Source: Economic Policy Institute, BEA, BLS, and author’s calculations.

Given the current median wage of just over $24 an hour, the full-year pay, net of payroll taxes (7.65 percent on the worker’s side) would be just under $46,600. By contrast, if their pay had kept pace with productivity growth over the last half-century, it would be over $79,700 net of payroll taxes.

If we said that it was necessary to raise the payroll tax by 4.0 percentage points (half on the employer and half on the employee) to deal with the cost of supporting an aging population, then the annual wage would fall to $76,500.[2] That would still be more than 70 percent above its current level.

The reality is that most workers stand to lose an order of magnitude more income due to upward redistribution than what they could conceivably risk from the changing demographics of the country. If we think that an aging population poses a risk to the living standards of younger workers, then upward redistribution is a disaster.

The Causes of Inequality

The hawkers of the demographic crisis story seem to want us to believe that inequality just happened and we just have to live with it. Of course, that is a lie. Inequality was the result of deliberate policy choices. We could have pursued different policies that would have not led to the rise in inequality we have seen over the last half century.

My book, Rigged, goes through the story in more detail, but I will quickly outline the basic picture. First, we have redistributed a massive amount of income upward with longer and stronger patent and copyright monopolies and related protections. Bill Gates would likely still be working for a living (actually, he could be collecting Social Security) if the government didn’t threaten to imprison people who made copies of Microsoft software without his permission.

It is common for economists to claim that technology was a major factor in upward redistribution. That is not true, it was our rules on technology that drove the upward redistribution. There are other, arguably more efficient, mechanisms for supporting innovation and creative work. These would likely not lead to as much inequality.

We also have pursued a narrow path of globalization where we quite deliberately put our manufacturing workers in direct competition with low-paid workers in the developing world. This had the predicted and actual effect of lowering the wages of manufacturing workers and non-college-educated workers more generally.

At the same time, we maintained or even increased the protections for highly educated professionals, like doctors and dentists. As a result, our doctors earn twice as much as doctors in other wealthy countries.

If we didn’t want to increase inequality, we could have pursued a course of globalization that focused foremost on reducing the barriers that protected our most highly paid workers. But these professionals, unlike manufacturing workers, have enough political power to ensure that trade deals will not be structured in ways that threaten their livelihood.

Our financial sector is a cesspool of waste and corruption. An efficient financial sector is a small financial sector. Instead of pursuing policies to promote efficiency, we have pursued policies that have encouraged bloat in this sector, which is the source of many of the biggest fortunes in the country.

When the market would have massively downsized the financial industry in the financial crisis, leaders of both political parties could not move quickly enough to rush to its rescue. There were no market fundamentalists when the great fortunes in the industry were in jeopardy.

We have also structured rules on corporate governance in ways that allow CEOs to rip off the companies they work for. The corporate directors, who are ostensibly charged with making sure CEOs and top management aren’t overpaid, for the most part, don’t even see this as part of their job description.

The bloated pay for CEOs warps the pay structure more generally. When a CEO can get $30 million and third-tier execs can get $2-$3 million, it creates a situation where even heads of charities and universities can command multi-million dollar paychecks.

High unemployment has also been a tool for lowering the pay of the typical worker. The only times where the pay of the median worker has outpaced inflation in the last half century have been when the unemployment rate was close to or below 4.0 percent.

The fact that anti-trust policy has been little used in the last four decades has likely also played a role in the recent shift from wages to profits. It will be interesting to see if the more aggressive policies pursued by the Biden administration have any effect in this area.

In short, we have made a series of policy decisions that have led to a massive upward redistribution of income in the last half-century. The impact of this upward redistribution on the income of young workers dwarfs the impact of demographics. Unfortunately, our news outlets seem more interested in highlighting the demographic issue than the causes of inequality.

There is one final point. We absolutely should be spending more money on daycare, healthcare for pregnant women and young children, early childhood education, and a variety of other areas that would benefit the young. However, there is no reason to believe that spending on the elderly is the obstacle preventing more spending in these areas.

[1] The median wage is taken from the Economic Policy Institute’s State of Working America data library. The 2022 was adjusted for the increase in the personal consumption expenditure deflator from 2022 to September of 2023 to get current dollars. Productivity growth since 1973 was adjusted for differences in deflators and the distinction between net and gross income, as well as the declining wage share of compensation to get the 2023 wage figure.

[2] Much of the projected shortfall in Social Security is a direct result of the upward redistribution of income since a larger share of wage income falls over the cap on taxable wage income (currently $186,600), as well as the shift from wages to profits in the last two decades.

Back in the 1990s, whining about the impending disaster from the retirement of baby boomer cohorts was all the rage. Private equity billionaire Peter Peterson’s polemics were big sellers, as very serious people struggled with how we could deal with this tidal wave of retirees. The basic story was that a rising ratio of retirees to workers would create a crushing burden for the younger people that were still in the labor force.

This argument went somewhat out of style over time. In part, the projection of exploding healthcare costs that drove the horror story turned out not to happen. Back in 2000, the long-term projections showed that healthcare would account for roughly one-third of total consumption spending by now. In fact, actual healthcare spending is less than 25.0 percent of total consumption. The difference between the 2000 projection and actual healthcare spending leaves about $1.5 trillion on the table (around $12k per family, each year) for us to spend on other things.

The second reason this demographic horror story went out of style was the slow recovery from the Great Recession. It took us over a decade to return to full employment following the collapse of the housing bubble. The problem for the economy in this decade was not that spending was too high, but rather that it was too low. (This is known as the “which way is up?” problem in economics.) If we had larger deficits during the last decade it would have provided a boost to growth and led to less unemployment.

Finally, the impending retirement of the baby boomers was no longer impending as they began to retire in the last decade. At the start of the decade the oldest baby boomers were already age 64. By 2020, the oldest baby boomers were age 74 and the youngest were already age 56. A substantial portion of the baby boom generation was already retired and the world had not ended.

The Return of the Demographic Crisis

But, as they say in Washington, no bad idea ever stays dead for long. In recent months the demographic crisis from retiring baby boomers seems to be everywhere. The major news outlets are filled with piece after piece telling us that we are running out of workers, at least when they are not telling us how the spread of robots and AI will create mass unemployment. (Yes, those claims are contradictory, but don’t tell any elite intellectual type.)

Anyhow, the basic story of the aging crisis is that workers will have to turn over a large portion of their paycheck to cover the costs of a growing population of retirees. This concern is supposed to lead us to cut Social Security and Medicare benefits and tell workers that they have to work later in life.

There are a couple of important points to be made at the start of any serious discussion. First, we have already raised the age at which people are eligible for full Social Security benefits. It had been 65 for people born before 1940. It has been gradually raised to 67 for people born after 1960. So, we have already taken account of people’s increased longevity in setting the parameters for Social Security.

The second point is that the gains in life expectancy have not been evenly shared. For people born in 1930 the gap in life expectancy, at age 50, between the top income quintile and the bottom income quintile for men was 5.0 years, and for women was 3.9 years. For the cohort born in 1960, the gap had increased to 12.7 years for men and 13.6 years for women. This means that almost all the gains in life expectancy over the last half century have been for those at the top of the income ladder. Those further down have seen little or no gains in life expectancy.

Next, it is important to have some idea of the dimensions of the aging “crisis.” We all know about the widely touted projected shortfalls in Social Security and Medicare. Let’s imagine that we made them up by raising the payroll tax. (That’s not the best way to deal with the problem, but this is just a hypothetical exercise.)

Suppose we raised the payroll tax by 4.0 percentage points tomorrow. Given current projections, this would be roughly enough to make the Social Security and Medicare trust funds solvent forever.

The graph below shows the current annual wage for a person getting the median wage, working full-time full year (50 weeks at 40 hours a week). It also shows what this worker would be getting if the median wage had kept pace with productivity growth, as it did in the long post-war boom from 1947 to 1973. And, it shows what this pay would have been if, in this scenario, we increased the payroll tax by 4.0 percentage points.[1]

Source: Economic Policy Institute, BEA, BLS, and author’s calculations.

Given the current median wage of just over $24 an hour, the full-year pay, net of payroll taxes (7.65 percent on the worker’s side) would be just under $46,600. By contrast, if their pay had kept pace with productivity growth over the last half-century, it would be over $79,700 net of payroll taxes.

If we said that it was necessary to raise the payroll tax by 4.0 percentage points (half on the employer and half on the employee) to deal with the cost of supporting an aging population, then the annual wage would fall to $76,500.[2] That would still be more than 70 percent above its current level.

The reality is that most workers stand to lose an order of magnitude more income due to upward redistribution than what they could conceivably risk from the changing demographics of the country. If we think that an aging population poses a risk to the living standards of younger workers, then upward redistribution is a disaster.

The Causes of Inequality

The hawkers of the demographic crisis story seem to want us to believe that inequality just happened and we just have to live with it. Of course, that is a lie. Inequality was the result of deliberate policy choices. We could have pursued different policies that would have not led to the rise in inequality we have seen over the last half century.

My book, Rigged, goes through the story in more detail, but I will quickly outline the basic picture. First, we have redistributed a massive amount of income upward with longer and stronger patent and copyright monopolies and related protections. Bill Gates would likely still be working for a living (actually, he could be collecting Social Security) if the government didn’t threaten to imprison people who made copies of Microsoft software without his permission.

It is common for economists to claim that technology was a major factor in upward redistribution. That is not true, it was our rules on technology that drove the upward redistribution. There are other, arguably more efficient, mechanisms for supporting innovation and creative work. These would likely not lead to as much inequality.

We also have pursued a narrow path of globalization where we quite deliberately put our manufacturing workers in direct competition with low-paid workers in the developing world. This had the predicted and actual effect of lowering the wages of manufacturing workers and non-college-educated workers more generally.

At the same time, we maintained or even increased the protections for highly educated professionals, like doctors and dentists. As a result, our doctors earn twice as much as doctors in other wealthy countries.

If we didn’t want to increase inequality, we could have pursued a course of globalization that focused foremost on reducing the barriers that protected our most highly paid workers. But these professionals, unlike manufacturing workers, have enough political power to ensure that trade deals will not be structured in ways that threaten their livelihood.

Our financial sector is a cesspool of waste and corruption. An efficient financial sector is a small financial sector. Instead of pursuing policies to promote efficiency, we have pursued policies that have encouraged bloat in this sector, which is the source of many of the biggest fortunes in the country.

When the market would have massively downsized the financial industry in the financial crisis, leaders of both political parties could not move quickly enough to rush to its rescue. There were no market fundamentalists when the great fortunes in the industry were in jeopardy.

We have also structured rules on corporate governance in ways that allow CEOs to rip off the companies they work for. The corporate directors, who are ostensibly charged with making sure CEOs and top management aren’t overpaid, for the most part, don’t even see this as part of their job description.

The bloated pay for CEOs warps the pay structure more generally. When a CEO can get $30 million and third-tier execs can get $2-$3 million, it creates a situation where even heads of charities and universities can command multi-million dollar paychecks.

High unemployment has also been a tool for lowering the pay of the typical worker. The only times where the pay of the median worker has outpaced inflation in the last half century have been when the unemployment rate was close to or below 4.0 percent.

The fact that anti-trust policy has been little used in the last four decades has likely also played a role in the recent shift from wages to profits. It will be interesting to see if the more aggressive policies pursued by the Biden administration have any effect in this area.

In short, we have made a series of policy decisions that have led to a massive upward redistribution of income in the last half-century. The impact of this upward redistribution on the income of young workers dwarfs the impact of demographics. Unfortunately, our news outlets seem more interested in highlighting the demographic issue than the causes of inequality.

There is one final point. We absolutely should be spending more money on daycare, healthcare for pregnant women and young children, early childhood education, and a variety of other areas that would benefit the young. However, there is no reason to believe that spending on the elderly is the obstacle preventing more spending in these areas.

[1] The median wage is taken from the Economic Policy Institute’s State of Working America data library. The 2022 was adjusted for the increase in the personal consumption expenditure deflator from 2022 to September of 2023 to get current dollars. Productivity growth since 1973 was adjusted for differences in deflators and the distinction between net and gross income, as well as the declining wage share of compensation to get the 2023 wage figure.

[2] Much of the projected shortfall in Social Security is a direct result of the upward redistribution of income since a larger share of wage income falls over the cap on taxable wage income (currently $186,600), as well as the shift from wages to profits in the last two decades.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Mark Twain famously quipped that everyone always talks about the weather, but no one ever does anything about it. (This was before global warming.) In the same vein, it is common for people to rant about billionaires, like Rupert Murdoch and Elon Musk, controlling major media outlets and using them to advance their political whims. But, no one seems to do anything about it.