• InequalityLa DesigualdadUnited StatesEE. UU.Wall StreetEl Mundo Financiero

Okay, that may not be as dramatic as imagining world peace, but hey, I’m an economist. And, as I will argue, more reasonably paid CEOs would be a pretty big deal.

Just to set the table, CEOs have always been well-paid. At least in principle, it is a demanding job requiring skills in many areas. I said “in principle” because the corporate scandals of the last few decades have surfaced many examples of CEOs whose primary skill seems to be in the art of bullshitting. But there can be little doubt that maintaining a well-run company does require serious skills and hard work.

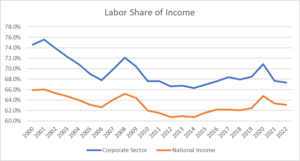

However, being a well-paid CEO means something very different today than it did fifty years ago. Back then, CEO pay was twenty to thirty times the pay of a typical worker. That would translate into roughly $2 million to $3 million a year given current pay structures.

Today, the average CEO of a major company is paid almost 400 times what an average worker earns, or roughly $25 million a year. There are issues of measurement that could make this figure higher or lower, but there is little doubt about the basic story where CEO pay has soared relative to the pay of ordinary workers and even relative to most other highly paid workers. [1]

While many of us might be offended by $25 million paychecks (the pay of 800 workers putting in a full year at the federal minimum wage) even if CEOs in some sense “earned” their pay, there is good reason to believe they don’t. There have been many studies showing that CEO pay does not closely correspond to returns to shareholders. A few examples are here, here, and here. Lucian Bebchuk and Jesse Fried’s book, Pay Without Performance, presents a wide range of evidence on this issue.

There is a simple story as to how CEO pay could become so divorced from their actual value to the companies they run. The basic picture is that there is no one to hold their pay down. We all understand how the pay of ordinary workers — retail clerks, assembly line workers, table servers in restaurant — are held down. Managers are supposed to keep their pay as low as possible, in order to maximize corporate profits.

If a company finds that they are paying their workers more than their competitors, they are likely to cut their pay to bring it into line. If current managers aren’t up to the task, the bosses find managers who will cut pay.[2]

But there is no remotely corresponding mechanism for CEO pay. The people who are supposed to hold their pay in check are the corporate boards of directors. The boards of directors ostensibly answer to shareholders, who elect the members of the board at regular intervals. However, as a practical matter, it is very difficult for shareholders to displace board members. More than 99 percent of the board members who are nominated by the rest of the board for re-election win their seats.

Being a board member is a very cushy job, typically paying well over $100,000 a year, and sometimes $300,000 or $400,000, for less than 400 hours of work, so board members generally want to keep their jobs. Since being re-nominated by the board virtually guarantees re-election, the best way to ensure that you get to hold onto your seat is to stay on good terms with other board members.[3]

This likely means not asking pesky questions like “can we pay our CEO less money?” Since top management plays a large role in selecting board members, it is not surprising that corporate boards tend to identify with them rather than shareholders. In fact, a recent survey of corporate directors found that the overwhelming majority did not even see limiting CEO pay as part of their job. Instead, they viewed their main role as serving the goals of management.

In this context, it is easy to tell a story where CEO pay can spiral upward almost without limit. Corporate boards are sitting on huge piles of money. They like their CEO and want to keep them happy. This means that they want to make sure their CEOs are paid at least as much as CEOs at their competitors. They do surveys so that they know what their competitors pay, and then add a ten or twenty percent premium.

And then their competitors do the same thing. They repeat this process every few years. In this story, CEO pay can only go up.

CEO Pay and Other High Earners

There has been much research in recent years showing how the pay of ordinary workers might bear little relationship to their actual output. There are two main stories. First, it appears that monopsonistic employment relationships are far more common than had previously been appreciated.

Rather than being an exceptional case, where for example there is one large employer in a small town, it seems many, if not most, employers have some degree of monopsony power. This means that rather than facing a horizontal supply curve, where they can hire as many workers as they want at the prevailing wage, paying one worker more money will also require paying other workers more money as well. In this context, workers will typically get paid less than their marginal product.

The other issue is that it seems workers may not typically be aware of their actual value in the labor market. They may not recognize how much they could earn at a different job, and therefore may accept pay that is less than their marginal product.

In both of these stories we can get situations persisting indefinitely where large numbers of workers may be earning substantially less than their marginal product. While this view is increasingly accepted for workers at the middle and bottom of the wage distribution, it is worth asking whether we may see comparable distortions at the high end, although in this case it would be a story with workers earning above their marginal product.

It is relatively easy to tell this story for CEOs and other top management, as discussed above. There basically is no market mechanism that would ensure CEO is kept in check. The corporate boards, that are supposed to work for shareholders in restraining in pay, tell us that they don’t even see this as part of their job. Of course, even if they said they were trying to rein in CEO pay, that is no guarantee they succeed, but when they tell us they are not even trying, we can be reasonably certain that they are not succeeding.[4]

But if pay for CEOs and other top managers is out of line with their marginal products, is it reasonable to believe that this is also likely the case for other highly paid workers. The story here is that the pay of CEOs and other top managers are a point of reference for other top-tier executives and high-level workers outside of the corporate sector.

We can think that workers enjoy a pay premium above their marginal product based on how close they are to corporate CEOs, both in the corporate hierarchy, and also in society more generally for people working outside the corporate sector. For other top-level executives this premium may be a large fraction of the CEO’s premium — say, something like 50 percent. This would mean that if the CEO gets $20 million more than their real value to the company, the chief financial officer and other C-suite executives get $10 million more than their real value.

For the next tier, the fraction might be something like 10 percent. In this case where the CEO is overpaid by $20 million, the third-tier executives will end up with $2 million more than their value to the company. There may still be some premium lower down, but once you get to the assembly line worker, it’s a safe bet it is zero.

To be clear, a third-tier executive is not getting inflated pay directly as a result of the inflated pay going to the CEO. Rather the CEO’s inflated pay is setting a pay structure (we use to talk about “wage contours”), that leads both workers and the people setting pay to think that the work of the third-tier executive is worth more than it actually is.

The same would apply to people working outside of the corporate sector. A university president may get something like an 8 percent CEO pay premium, which would mean that $20 million in excess pay for the average CEO is raising their pay by $1.6 million. The next level of university administration may get something like a 4 percent CEO premium, with excessive CEO pay adding $800,000 a year to their paychecks.

If this story is accurate, then it would not be easy to disrupt the pay structure. If a top university decided to pay its president $1 million rather than $2 million, it would be seen as an insult, given prevailing pay scales. An incumbent president would likely leave if they faced this sort of pay cut and many potential candidates for an open position offering half of the prevailing pay for university presidents would opt not to seek the job.

The norms around pay have real power in the world. If workers, and especially high-end workers, don’t feel they are being paid fairly, it is likely to show up in their performance. And, even if the pay for CEOs may exceed their value, a CEO or high-end worker who is trying to sabotage their employer is definitely in a situation to do considerable damage. This means it is difficult for an individual company to try to make the pay of their higher-level employees more closely reflect their actual value.

This suggests that bringing the exorbitant pay of CEOs, and other high-level workers, back in line with their value, will have to involve a process that takes place through time, similar to the process that led to the run-up in pay over the last five decades, but in the opposite direction. And, it should start at the top.

Setting the Ship Straight – Getting the Incentives Right

There have been various proposals for lowering the pay of CEOs, many of which involve some form of direct government intervention, such as a tax penalty for companies with overpaid CEOs. While corporations, with or without overpaid CEOs, can certainly afford to pay more taxes, I respect their enormous ability to avoid taxation. (Here’s my scheme for cracking down on corporate tax avoidance/evasion.)

I prefer a route that changes incentives. At it stands now, the corporate boards that most directly determine CEO pay have essentially zero incentive to try to lower pay. We should take seriously what these boards tell us; they see their jobs as serving top management. They are sitting on piles of money, which are not theirs. They know that they can keep top management happy by giving them generous paychecks. In this context, bloated CEO pay should not surprise us.

But we can change the incentives. The Dodd-Frank financial reform legislation included a “Say on Pay” provision, which required companies to send out their CEO pay package for shareholder approval at three-year intervals. The vote is simply a yes or no vote. There is no direct consequence for a pay package being voted down, but presumably it is an embarrassment to both the CEO and the board.

As it stands, very few pay packages are voted down. Less than 3.0 percent of Say on Pay votes lose. It is very difficult to organize diffuse shareholders, and since there is little consequence to a “no” vote, there is not much incentive for anyone to try.

However, we could put some meat on the bones. Suppose that the board of directors would lose their pay for the year if a CEO package was voted down. This would be a clear substantive outcome that might encourage more shareholders, who are disturbed by an excessive pay package, to make the effort to try organize among shareholders.

It is also likely that this would get the attention of corporate boards. My guess is that once two or three boards were forced to sacrifice their paychecks as a result of losing a Say on Pay vote, directors would become far more careful in dishing out dollars to top executives. In that world, they may decide it is actually a good thing if their CEO was paid somewhat less than their peer group. And, over time, we might see CEO pay fall back in line with their actual productivity.

While many people seem to view this plan to punish directors for excessive CEO pay as a left-wing proposal, it is hard to understand what is radical about giving shareholders more control over the company they ostensibly own. Presumably, this is exactly what fans of the free market would want.

After all, what possible incentive would shareholders have for paying a CEO less than their true value? This would mean that they would get lower returns on their stock if they ended up with an inept CEO because they weren’t paying the market price for a competent one.

Of course, it is hard to say how corporate boards would respond, and maybe CEOs really are worth their eight-figure paychecks, in spite of the evidence to the contrary. But it seems worth a try. We know that under the current system, there is no one who has the job of keeping CEO pay in check, and we pay a high price in the form of inequality, and less money for everyone else, as a result of the bloated pay structure at the top.

There seems little harm in trying to get the market to function as the textbooks say it does, and have the CEOs actually work for shareholders.

[1] The analysis cited, by Josh Bivens and Jori Kandra, excludes the pay of Tesla CEO Elon Musk. In 2021, the year analyzed, he cashed out stock options worth $23.5 billion. Had this been included in the sample of CEOs, it would have pushed average CEO pay for the sample to almost $100 million. On the other hand, Bivens and Kandra use the realized value of stock options rather than the value at the point where they are issued. Arguably, the latter is a better measure of compensation, since that is most immediately what the CEO is paid.

[2] There are exceptions, like Costco, who quite explicitly pay their workers more than competitors, but this is done with the idea that they will get more loyalty and more productive workers. This is a deliberate policy — it is not an accident.

[3] The board dynamics around CEO pay are discussed in Steven Clifford’s great book, the CEO Pay Machine.

[4] It is sometimes argued that the pay of CEOs at companies owned by private equity provides a good test of the true worth of CEOs, since there is no issue of diffused shareholder ownership. The pay of CEOs at private equity owned companies tends to be comparable or higher than their pay at publicly traded companies. However, the meaning of this comparison is questionable. Private equity firms usually look to hold a company for only a few years, working a major restructuring and then reselling it as a publicly traded company. This means both that they are likely making extraordinary demands on a CEO during this period, and that they face exceptional risk from bad performance. If they paid less than prevailing CEO salaries, they might get poor performing CEOs who would doom their project.

Okay, that may not be as dramatic as imagining world peace, but hey, I’m an economist. And, as I will argue, more reasonably paid CEOs would be a pretty big deal.

Just to set the table, CEOs have always been well-paid. At least in principle, it is a demanding job requiring skills in many areas. I said “in principle” because the corporate scandals of the last few decades have surfaced many examples of CEOs whose primary skill seems to be in the art of bullshitting. But there can be little doubt that maintaining a well-run company does require serious skills and hard work.

However, being a well-paid CEO means something very different today than it did fifty years ago. Back then, CEO pay was twenty to thirty times the pay of a typical worker. That would translate into roughly $2 million to $3 million a year given current pay structures.

Today, the average CEO of a major company is paid almost 400 times what an average worker earns, or roughly $25 million a year. There are issues of measurement that could make this figure higher or lower, but there is little doubt about the basic story where CEO pay has soared relative to the pay of ordinary workers and even relative to most other highly paid workers. [1]

While many of us might be offended by $25 million paychecks (the pay of 800 workers putting in a full year at the federal minimum wage) even if CEOs in some sense “earned” their pay, there is good reason to believe they don’t. There have been many studies showing that CEO pay does not closely correspond to returns to shareholders. A few examples are here, here, and here. Lucian Bebchuk and Jesse Fried’s book, Pay Without Performance, presents a wide range of evidence on this issue.

There is a simple story as to how CEO pay could become so divorced from their actual value to the companies they run. The basic picture is that there is no one to hold their pay down. We all understand how the pay of ordinary workers — retail clerks, assembly line workers, table servers in restaurant — are held down. Managers are supposed to keep their pay as low as possible, in order to maximize corporate profits.

If a company finds that they are paying their workers more than their competitors, they are likely to cut their pay to bring it into line. If current managers aren’t up to the task, the bosses find managers who will cut pay.[2]

But there is no remotely corresponding mechanism for CEO pay. The people who are supposed to hold their pay in check are the corporate boards of directors. The boards of directors ostensibly answer to shareholders, who elect the members of the board at regular intervals. However, as a practical matter, it is very difficult for shareholders to displace board members. More than 99 percent of the board members who are nominated by the rest of the board for re-election win their seats.

Being a board member is a very cushy job, typically paying well over $100,000 a year, and sometimes $300,000 or $400,000, for less than 400 hours of work, so board members generally want to keep their jobs. Since being re-nominated by the board virtually guarantees re-election, the best way to ensure that you get to hold onto your seat is to stay on good terms with other board members.[3]

This likely means not asking pesky questions like “can we pay our CEO less money?” Since top management plays a large role in selecting board members, it is not surprising that corporate boards tend to identify with them rather than shareholders. In fact, a recent survey of corporate directors found that the overwhelming majority did not even see limiting CEO pay as part of their job. Instead, they viewed their main role as serving the goals of management.

In this context, it is easy to tell a story where CEO pay can spiral upward almost without limit. Corporate boards are sitting on huge piles of money. They like their CEO and want to keep them happy. This means that they want to make sure their CEOs are paid at least as much as CEOs at their competitors. They do surveys so that they know what their competitors pay, and then add a ten or twenty percent premium.

And then their competitors do the same thing. They repeat this process every few years. In this story, CEO pay can only go up.

CEO Pay and Other High Earners

There has been much research in recent years showing how the pay of ordinary workers might bear little relationship to their actual output. There are two main stories. First, it appears that monopsonistic employment relationships are far more common than had previously been appreciated.

Rather than being an exceptional case, where for example there is one large employer in a small town, it seems many, if not most, employers have some degree of monopsony power. This means that rather than facing a horizontal supply curve, where they can hire as many workers as they want at the prevailing wage, paying one worker more money will also require paying other workers more money as well. In this context, workers will typically get paid less than their marginal product.

The other issue is that it seems workers may not typically be aware of their actual value in the labor market. They may not recognize how much they could earn at a different job, and therefore may accept pay that is less than their marginal product.

In both of these stories we can get situations persisting indefinitely where large numbers of workers may be earning substantially less than their marginal product. While this view is increasingly accepted for workers at the middle and bottom of the wage distribution, it is worth asking whether we may see comparable distortions at the high end, although in this case it would be a story with workers earning above their marginal product.

It is relatively easy to tell this story for CEOs and other top management, as discussed above. There basically is no market mechanism that would ensure CEO is kept in check. The corporate boards, that are supposed to work for shareholders in restraining in pay, tell us that they don’t even see this as part of their job. Of course, even if they said they were trying to rein in CEO pay, that is no guarantee they succeed, but when they tell us they are not even trying, we can be reasonably certain that they are not succeeding.[4]

But if pay for CEOs and other top managers is out of line with their marginal products, is it reasonable to believe that this is also likely the case for other highly paid workers. The story here is that the pay of CEOs and other top managers are a point of reference for other top-tier executives and high-level workers outside of the corporate sector.

We can think that workers enjoy a pay premium above their marginal product based on how close they are to corporate CEOs, both in the corporate hierarchy, and also in society more generally for people working outside the corporate sector. For other top-level executives this premium may be a large fraction of the CEO’s premium — say, something like 50 percent. This would mean that if the CEO gets $20 million more than their real value to the company, the chief financial officer and other C-suite executives get $10 million more than their real value.

For the next tier, the fraction might be something like 10 percent. In this case where the CEO is overpaid by $20 million, the third-tier executives will end up with $2 million more than their value to the company. There may still be some premium lower down, but once you get to the assembly line worker, it’s a safe bet it is zero.

To be clear, a third-tier executive is not getting inflated pay directly as a result of the inflated pay going to the CEO. Rather the CEO’s inflated pay is setting a pay structure (we use to talk about “wage contours”), that leads both workers and the people setting pay to think that the work of the third-tier executive is worth more than it actually is.

The same would apply to people working outside of the corporate sector. A university president may get something like an 8 percent CEO pay premium, which would mean that $20 million in excess pay for the average CEO is raising their pay by $1.6 million. The next level of university administration may get something like a 4 percent CEO premium, with excessive CEO pay adding $800,000 a year to their paychecks.

If this story is accurate, then it would not be easy to disrupt the pay structure. If a top university decided to pay its president $1 million rather than $2 million, it would be seen as an insult, given prevailing pay scales. An incumbent president would likely leave if they faced this sort of pay cut and many potential candidates for an open position offering half of the prevailing pay for university presidents would opt not to seek the job.

The norms around pay have real power in the world. If workers, and especially high-end workers, don’t feel they are being paid fairly, it is likely to show up in their performance. And, even if the pay for CEOs may exceed their value, a CEO or high-end worker who is trying to sabotage their employer is definitely in a situation to do considerable damage. This means it is difficult for an individual company to try to make the pay of their higher-level employees more closely reflect their actual value.

This suggests that bringing the exorbitant pay of CEOs, and other high-level workers, back in line with their value, will have to involve a process that takes place through time, similar to the process that led to the run-up in pay over the last five decades, but in the opposite direction. And, it should start at the top.

Setting the Ship Straight – Getting the Incentives Right

There have been various proposals for lowering the pay of CEOs, many of which involve some form of direct government intervention, such as a tax penalty for companies with overpaid CEOs. While corporations, with or without overpaid CEOs, can certainly afford to pay more taxes, I respect their enormous ability to avoid taxation. (Here’s my scheme for cracking down on corporate tax avoidance/evasion.)

I prefer a route that changes incentives. At it stands now, the corporate boards that most directly determine CEO pay have essentially zero incentive to try to lower pay. We should take seriously what these boards tell us; they see their jobs as serving top management. They are sitting on piles of money, which are not theirs. They know that they can keep top management happy by giving them generous paychecks. In this context, bloated CEO pay should not surprise us.

But we can change the incentives. The Dodd-Frank financial reform legislation included a “Say on Pay” provision, which required companies to send out their CEO pay package for shareholder approval at three-year intervals. The vote is simply a yes or no vote. There is no direct consequence for a pay package being voted down, but presumably it is an embarrassment to both the CEO and the board.

As it stands, very few pay packages are voted down. Less than 3.0 percent of Say on Pay votes lose. It is very difficult to organize diffuse shareholders, and since there is little consequence to a “no” vote, there is not much incentive for anyone to try.

However, we could put some meat on the bones. Suppose that the board of directors would lose their pay for the year if a CEO package was voted down. This would be a clear substantive outcome that might encourage more shareholders, who are disturbed by an excessive pay package, to make the effort to try organize among shareholders.

It is also likely that this would get the attention of corporate boards. My guess is that once two or three boards were forced to sacrifice their paychecks as a result of losing a Say on Pay vote, directors would become far more careful in dishing out dollars to top executives. In that world, they may decide it is actually a good thing if their CEO was paid somewhat less than their peer group. And, over time, we might see CEO pay fall back in line with their actual productivity.

While many people seem to view this plan to punish directors for excessive CEO pay as a left-wing proposal, it is hard to understand what is radical about giving shareholders more control over the company they ostensibly own. Presumably, this is exactly what fans of the free market would want.

After all, what possible incentive would shareholders have for paying a CEO less than their true value? This would mean that they would get lower returns on their stock if they ended up with an inept CEO because they weren’t paying the market price for a competent one.

Of course, it is hard to say how corporate boards would respond, and maybe CEOs really are worth their eight-figure paychecks, in spite of the evidence to the contrary. But it seems worth a try. We know that under the current system, there is no one who has the job of keeping CEO pay in check, and we pay a high price in the form of inequality, and less money for everyone else, as a result of the bloated pay structure at the top.

There seems little harm in trying to get the market to function as the textbooks say it does, and have the CEOs actually work for shareholders.

[1] The analysis cited, by Josh Bivens and Jori Kandra, excludes the pay of Tesla CEO Elon Musk. In 2021, the year analyzed, he cashed out stock options worth $23.5 billion. Had this been included in the sample of CEOs, it would have pushed average CEO pay for the sample to almost $100 million. On the other hand, Bivens and Kandra use the realized value of stock options rather than the value at the point where they are issued. Arguably, the latter is a better measure of compensation, since that is most immediately what the CEO is paid.

[2] There are exceptions, like Costco, who quite explicitly pay their workers more than competitors, but this is done with the idea that they will get more loyalty and more productive workers. This is a deliberate policy — it is not an accident.

[3] The board dynamics around CEO pay are discussed in Steven Clifford’s great book, the CEO Pay Machine.

[4] It is sometimes argued that the pay of CEOs at companies owned by private equity provides a good test of the true worth of CEOs, since there is no issue of diffused shareholder ownership. The pay of CEOs at private equity owned companies tends to be comparable or higher than their pay at publicly traded companies. However, the meaning of this comparison is questionable. Private equity firms usually look to hold a company for only a few years, working a major restructuring and then reselling it as a publicly traded company. This means both that they are likely making extraordinary demands on a CEO during this period, and that they face exceptional risk from bad performance. If they paid less than prevailing CEO salaries, they might get poor performing CEOs who would doom their project.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

• Intellectual PropertyPropiedad IntelectualUnited StatesEE. UU.

There has been a lot of concern in recent days about the impact of AI on people’s intellectual property. The latest AI programs screen millions of documents, songs, pictures, and videos posted to the web and freely grab any portion that seems to fit the commands given the program. As it stands, the creators of the material are not compensated, even if a large portion of their work appears in the AI product.

This raises serious questions about how AI will affect the future of intellectual property. To my mind, we should keep the focus on three distinct points:

Compensating Creative Workers

Starting with the first point, we have long recognized that a market that does not have some explicit mechanism for subsidizing creative work will underproduce creative work. People write, sing, paint, and do other creative work because they enjoy it, but we cannot expect to get as much of these products as society wants if we don’t pay people to do them. A musician or writer who has to spend eight hours a day bussing tables to pay the rent is not going to be able to devote themselves fully to developing their talents in these areas.

For this reason, we have long recognized the need for mechanisms to support creative work. This is the logic of copyright monopolies. By granting creative workers a legally enforceable monopoly on their work, we give them more of an opportunity to get compensated than if everything was immediately available in a free market. If a song could be immediately copied endlessly, with no compensation to the songwriters or musicians, they would get no compensation for any recorded work. The same would apply to writers, photographers, and many other creative workers.

Copyright monopolies can enable creative workers to get compensation, and possibly substantial compensation, if their work is popular. This is the logic of the clause in the Constitution allowing Congress to grant copyright monopolies.

It is important to recognize that the provision in the Constitution providing the basis for copyright quite explicitly describes it as serving a public purpose; it is not an individual right. The provision, Article 1, Section 8, clause 8, sets it out as a power of Congress:

“To promote the progress of science and useful arts, by securing for limited times to authors and inventors the exclusive right to their respective writings and discoveries.”

This appears alongside other powers of Congress, such as the power to tax and the power to declare war. The logic is quite clear: copyright is to serve the public purpose of promoting the “progress of science and art.” It is not a right of individuals included in the Bill of Rights along with freedom of speech or freedom of the press. This is an important point to keep in mind when assessing the merits of copyrights and alternatives in the AI age.

The Cost of Copyright Enforcement

Copyright enforcement has always been expensive, meaning that the costs of policing copyright, including legal fees and related costs, are high relative to the money actually given to creative workers. At the most immediate level, the creative workers who are ostensible beneficiaries of copyright monopolies often have to pay substantial sums to have their copyrights enforced.

The American Society of Composers, Authors, and Musicians (ASCAP), which is the major agent for collecting royalties for creative workers, reports that it pays out 90 percent of the money it collects in royalties. While that may sound pretty good, the money that a creative worker might have to pay to lawyers and agents comes out of this 90 percent. While creative workers are likely to need agents in any case, any legal fees they face will likely be associated with copyright issues. If legal fees associated with copyrights average 10 percent of their royalties for creative workers, then copyright related costs would be around 25 percent of their income from copyrights.

It’s also worth noting the sort of money involved. In 2021, ASCAP took in $1,335 million in royalty payments. The organization has 900,000 members, which means the average amount was less than $1,500 per person. Given the enormous skewing of these payments, with a relatively small number of creative workers getting a grossly disproportionate share of royalties, it is likely that the annual royalties for many ASCAP members are in the double or even single digits.

While copyright monopolies may mean little income for the vast majority of creative workers, they can impose large costs on society. This is largely due to how we have chosen to structure copyright law. In addition to actual damages, a person alleging copyright infringement is also eligible for statutory damages. These can run into the thousands, or even tens of thousands, of dollars. The person alleging infringement can also win attorney fees, which can run into the thousands of dollars as well.[1]

Spotify pays musicians between 0.3-0.5 cents per stream. Suppose someone posts infringing material on a website, which allows for 10,000 people to hear a copyrighted song. The actual damages in this case would be in the neighborhood of $30 to $50. Nonetheless, the infringer could end up paying many thousand dollars in damages and legal fees, an amount that could be easily hundreds of times the actual damage.

The Digital Millennial Copyright Act (DMCA) applies copyright law to the Internet. The DMCA requires Internet intermediaries, like Facebook or Twitter, to promptly remove content posted by third parties after being notified by a copyright holder, or their agent, of risk liability. According to several analyses, intermediaries typically err on the side of over-removal, taking down items which are arguably allowable under Fair Use, or where the infringement allegation does not come from someone who had a clear copyright claim.[2]

As a result, people go to great lengths to avoid inadvertently using copyrighted material. For example, anyone producing a movie or television show would thoroughly screen all the material to ensure that none of it is copyright protected. An independent producer would likely have to pay for insurance before a television station or streaming service would circulate their movie or show.

There also are undoubtedly many cases where material is altered due to ambiguities on copyright. Since there is no registration requirement, it can be almost impossible to determine if a copyright is applicable.

For example, if someone producing a documentary on the Sixties uncovered an old photograph, with no obvious commercial value, that would be useful for making a particular point, they would be taking a risk to include it. The person who took the photograph, or a family member, may be able to claim copyright ownership, and file a suit for an amount that exceeds whatever the filmmaker hoped to earn from the documentary.

Copyright can also impose a cost by obstructing the production of derivative works. There have been endless battles over people seeking to write fiction, parodies, songs, or other types of creative work based on famous fictional characters, such as Harry Potter or Sherlock Holmes. Arguably, we suffer a loss as a society by preventing these creative ventures. Fortunately, William Shakespeare’s work was no longer copyright protected when Tom Stoppard wrote “Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are Dead.”

There are also endless examples of copyright enforcement absurdities, such as when the Girls Scouts were threatened by ASCAP with a lawsuit for singing copyrighted songs around campfires without permission. (ASCAP later backed down and apologized.) More recently, Carol Highsmith, a photographer, got a cease and desist letter from Getty Images for posting her own photograph, which she had placed in the public domain and donated to the Library of Congress, on her own website.

There is a pretty much endless supply of these sorts of stories, but the point should be clear: copyright enforcement creates all sorts of issues that would not exist in a copyright free world, where basically all digital material could be obtained immediately at zero cost. Copyright is a way to support creative work, but arguably not a very good one. The Internet already raised the costs associated with copyright enforcement substantially. If we have to impose all sorts restrictions on AI, in order to protect copyrights, then the cost to society of copyright enforcement will rise further.

Alternatives to Copyright Monopolies for Supporting Creative Work

There are many other ways we can and do support creative work. The most obvious is with direct government subsidies. These subsidies are far more common in Europe than in the United States, but governments can pay out money to musicians, movie producers, writers and other creative workers. Even in the United States, we do commit relatively small amounts of money for this purpose through agencies like the National Endowment for the Arts.

However, having government agencies support creative work does raise political issues about what work should be supported. Fortunately, we have an alternative that already exists, even if it is not generally considered as a mechanism for supporting creative work.

The charitable contribution tax deduction is a way the government supports a wide variety of non-profit organizations. In many cases, such as orchestras, operas, art and culture programs, these contributions support people doing creative work. As it stands of course, the vast majority of these deductions are not for creative work, and the bulk of the benefit goes to high income people who both itemize on their tax returns and also are in the top marginal income bracket, which means the deduction would be worth more.

However, the charitable contribution tax deduction can serve as useful model. Instead of having a tax deduction, we could create a tax credit, say $100 to $200 per person. And, we could stipulate that the credit can only be used to support creative workers or organizations that support creative work. The latter could be organizations that commit themselves to supporting say, mystery writers or country music singers, which would serve as intermediaries for people who don’t want to use their credit for supporting specific individuals.

To be eligible to receive the funding, a person or organization would have to register in the same way that an organization has to register now with the I.R.S. to get tax exempt status. This would mean effectively saying what it is they do, as in write music, or play guitar. As is the case now, there would no effort to determine whether a particular individual or organization is good at what they do, just as the I.R.S. doesn’t try to determine if a church is a good church or a museum is a good museum. The only issue is preventing fraud, ensuring that they do what they claim to do. [3]

The other condition of eligibility is that workers would lose copyright protection for the time they are in the tax credit system and a substantial period (e.g. five years) afterwards. The point is that we only subsidize creative work once. If we pay the worker to produce a book or movie or song, we don’t have to pay them a second time by granting them a copyright monopoly.

The logic of having a ban on copyright protection for a period after being in the system is to avoid having people using the tax credit system as an effective farm system, where they develop a reputation and then join the copyright system. They would still have the option to change systems, but they would have to wait for a period of time.

A nice feature of this provision is that it is effectively self-enforcing. If a person breaks the rules and seeks to get a copyright for their work a year after they leave the tax credit system, they would find themselves unable to enforce the copyright. If they attempted to take legal action against someone for infringement, the defendant need only point to the fact that they had been registered in the tax credit system the prior year. Therefore, their copyright is not valid. (I discuss this system in somewhat more detail in chapter 5 of Rigged [it’s free].)

This sort of system could produce a vast amount of creative work that could be freely reproduced and transferred without any concerns about copyright. If AI programs wanted to scrape them to create new works, there would be no issue of compensation, the producers having already been compensated. A rule that could be applied (obviously this requires more thought) is some sort acknowledgement in an AI-produced work, much as any scholarly article includes a reference section for work that it draws on. This would prevent outright plagiarism by an AI program and also give credit to the creative workers who it relied upon for a derivative work. This is also something that presumably could be very easily programmed into any AI system.

I have heard people complain about the fact that this tax credit system would mean that creative workers would lose control over their work. For example, if some racist politician wanted to use their song at a campaign rally, they would have no way to stop them. This is true, but there are a couple of points worth keeping in mind.

First, even under the copyright system many creative workers sign over the rights to their work, so they already would not have the ability to prevent their work from being used in ways they found distasteful. Second, most people in society don’t have the ability to control what is done with their work. For example, jokes can’t be copyrighted. If someone writes a joke that a racist politician decided is the perfect line to start their campaign stump speech, there is nothing the joke writer can do about it, except complain. It’s hard to see why a musician or songwriter should have more right to control what is done with their work than a comedy writer.

Second, many people find their work used for purposes of which they strongly disapprove. Many of the physicists whose discoveries laid the groundwork for the development of the atomic bomb were pacifists. They were appalled that their work could be used to create a weapon of mass destruction. But there was nothing they could do about it. That seems a more serious complaint that a distasteful politician using a song without permission.

Copyright with a Tax Credit System

In principle, there is no reason that a tax credit system could not exist side by side with the copyright system. There could be many creative workers, which would likely include many well-established stars, who would opt to stay in the copyright system. In any case, there would still be a vast amount of material already protected by copyright.

As a general matter of principle, it is a good policy to respect property rights after they have been granted, even if it may have been a bad idea to grant those rights in the first place. For this reason, it would be appropriate to continue to respect existing copyrights. However, we can make an important change in the rules.

Copyright suits need not be eligible for statutory damages. If my neighbor knocks over my fence with their SUV, I can sue them for the cost of repairing my fence. I don’t also get statutory damages and usually would not be able to collect attorney fees. We don’t have to give this special status to those bringing lawsuits for copyright infringement.

This is likely to mean far fewer occasions for lawsuits for copyright infringement, which means fewer resources would be wasted contesting these suits and taking steps to prevent them. This could also make the copyright system less attractive relative to the tax credit system. If that turned out to be the case, that seems like a great outcome.

Time to Re-evaluate Copyright Monopolies, not AI

This is obviously a very superficial discussion of issues arising with AI. It also only a portion of the copyright related issues. For example, copyright also comes up with software and there are likely to be many instances where AI programs arguably infringe on copyrighted software.

However, the key point is that we should not treat our current rules on intellectual property as set in stone. When the Internet first became an important development in the 1990s, at the urging of the music industry, Congress rushed to pass the Digital Millennial Copyright Act, to ensure that copyrights would be enforced on the web. This limited the potential of the Internet as a means to freely transfer information, articles, books, music, and movies and other digital material.

Now we are hearing similar concerns about how AI will affect the value of copyrighted material. Rather than limiting AI, it might be more appropriate to reconsider copyright and determine whether it is still the best mechanism for supporting creative work. As I argue here, there are good reasons for thinking that is not the case.

[1] A provision in the Trans-Pacific Partnership would have required countries to have criminal penalties for copyright infringement.

[2] Note that the law with regard to copyright enforcement is the exact opposite of what it holds for third party content with regards to allegations of defamation. As a result of Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act, Facebook, Twitter and other Internet intermediaries can freely host defamatory material, and even profit from it directly when they sell ads, without any risk of legal consequences.

[3] It would be necessary to have rules to prevent simple scams. For example, in order to be able to receive the credit, there could be a requirement that a person gets at least $3,000. This would prevent any simple trading scheme where people exchange credits with each other. While it would still be possible have some pooling and kickbacks even with a $3,000 or similar size minimum, this would require a lot of work for relatively little money. Furthermore, it is much easier to organize a much larger kickback scheme with the current chartable deduction.

There has been a lot of concern in recent days about the impact of AI on people’s intellectual property. The latest AI programs screen millions of documents, songs, pictures, and videos posted to the web and freely grab any portion that seems to fit the commands given the program. As it stands, the creators of the material are not compensated, even if a large portion of their work appears in the AI product.

This raises serious questions about how AI will affect the future of intellectual property. To my mind, we should keep the focus on three distinct points:

Compensating Creative Workers

Starting with the first point, we have long recognized that a market that does not have some explicit mechanism for subsidizing creative work will underproduce creative work. People write, sing, paint, and do other creative work because they enjoy it, but we cannot expect to get as much of these products as society wants if we don’t pay people to do them. A musician or writer who has to spend eight hours a day bussing tables to pay the rent is not going to be able to devote themselves fully to developing their talents in these areas.

For this reason, we have long recognized the need for mechanisms to support creative work. This is the logic of copyright monopolies. By granting creative workers a legally enforceable monopoly on their work, we give them more of an opportunity to get compensated than if everything was immediately available in a free market. If a song could be immediately copied endlessly, with no compensation to the songwriters or musicians, they would get no compensation for any recorded work. The same would apply to writers, photographers, and many other creative workers.

Copyright monopolies can enable creative workers to get compensation, and possibly substantial compensation, if their work is popular. This is the logic of the clause in the Constitution allowing Congress to grant copyright monopolies.

It is important to recognize that the provision in the Constitution providing the basis for copyright quite explicitly describes it as serving a public purpose; it is not an individual right. The provision, Article 1, Section 8, clause 8, sets it out as a power of Congress:

“To promote the progress of science and useful arts, by securing for limited times to authors and inventors the exclusive right to their respective writings and discoveries.”

This appears alongside other powers of Congress, such as the power to tax and the power to declare war. The logic is quite clear: copyright is to serve the public purpose of promoting the “progress of science and art.” It is not a right of individuals included in the Bill of Rights along with freedom of speech or freedom of the press. This is an important point to keep in mind when assessing the merits of copyrights and alternatives in the AI age.

The Cost of Copyright Enforcement

Copyright enforcement has always been expensive, meaning that the costs of policing copyright, including legal fees and related costs, are high relative to the money actually given to creative workers. At the most immediate level, the creative workers who are ostensible beneficiaries of copyright monopolies often have to pay substantial sums to have their copyrights enforced.

The American Society of Composers, Authors, and Musicians (ASCAP), which is the major agent for collecting royalties for creative workers, reports that it pays out 90 percent of the money it collects in royalties. While that may sound pretty good, the money that a creative worker might have to pay to lawyers and agents comes out of this 90 percent. While creative workers are likely to need agents in any case, any legal fees they face will likely be associated with copyright issues. If legal fees associated with copyrights average 10 percent of their royalties for creative workers, then copyright related costs would be around 25 percent of their income from copyrights.

It’s also worth noting the sort of money involved. In 2021, ASCAP took in $1,335 million in royalty payments. The organization has 900,000 members, which means the average amount was less than $1,500 per person. Given the enormous skewing of these payments, with a relatively small number of creative workers getting a grossly disproportionate share of royalties, it is likely that the annual royalties for many ASCAP members are in the double or even single digits.

While copyright monopolies may mean little income for the vast majority of creative workers, they can impose large costs on society. This is largely due to how we have chosen to structure copyright law. In addition to actual damages, a person alleging copyright infringement is also eligible for statutory damages. These can run into the thousands, or even tens of thousands, of dollars. The person alleging infringement can also win attorney fees, which can run into the thousands of dollars as well.[1]

Spotify pays musicians between 0.3-0.5 cents per stream. Suppose someone posts infringing material on a website, which allows for 10,000 people to hear a copyrighted song. The actual damages in this case would be in the neighborhood of $30 to $50. Nonetheless, the infringer could end up paying many thousand dollars in damages and legal fees, an amount that could be easily hundreds of times the actual damage.

The Digital Millennial Copyright Act (DMCA) applies copyright law to the Internet. The DMCA requires Internet intermediaries, like Facebook or Twitter, to promptly remove content posted by third parties after being notified by a copyright holder, or their agent, of risk liability. According to several analyses, intermediaries typically err on the side of over-removal, taking down items which are arguably allowable under Fair Use, or where the infringement allegation does not come from someone who had a clear copyright claim.[2]

As a result, people go to great lengths to avoid inadvertently using copyrighted material. For example, anyone producing a movie or television show would thoroughly screen all the material to ensure that none of it is copyright protected. An independent producer would likely have to pay for insurance before a television station or streaming service would circulate their movie or show.

There also are undoubtedly many cases where material is altered due to ambiguities on copyright. Since there is no registration requirement, it can be almost impossible to determine if a copyright is applicable.

For example, if someone producing a documentary on the Sixties uncovered an old photograph, with no obvious commercial value, that would be useful for making a particular point, they would be taking a risk to include it. The person who took the photograph, or a family member, may be able to claim copyright ownership, and file a suit for an amount that exceeds whatever the filmmaker hoped to earn from the documentary.

Copyright can also impose a cost by obstructing the production of derivative works. There have been endless battles over people seeking to write fiction, parodies, songs, or other types of creative work based on famous fictional characters, such as Harry Potter or Sherlock Holmes. Arguably, we suffer a loss as a society by preventing these creative ventures. Fortunately, William Shakespeare’s work was no longer copyright protected when Tom Stoppard wrote “Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are Dead.”

There are also endless examples of copyright enforcement absurdities, such as when the Girls Scouts were threatened by ASCAP with a lawsuit for singing copyrighted songs around campfires without permission. (ASCAP later backed down and apologized.) More recently, Carol Highsmith, a photographer, got a cease and desist letter from Getty Images for posting her own photograph, which she had placed in the public domain and donated to the Library of Congress, on her own website.

There is a pretty much endless supply of these sorts of stories, but the point should be clear: copyright enforcement creates all sorts of issues that would not exist in a copyright free world, where basically all digital material could be obtained immediately at zero cost. Copyright is a way to support creative work, but arguably not a very good one. The Internet already raised the costs associated with copyright enforcement substantially. If we have to impose all sorts restrictions on AI, in order to protect copyrights, then the cost to society of copyright enforcement will rise further.

Alternatives to Copyright Monopolies for Supporting Creative Work

There are many other ways we can and do support creative work. The most obvious is with direct government subsidies. These subsidies are far more common in Europe than in the United States, but governments can pay out money to musicians, movie producers, writers and other creative workers. Even in the United States, we do commit relatively small amounts of money for this purpose through agencies like the National Endowment for the Arts.

However, having government agencies support creative work does raise political issues about what work should be supported. Fortunately, we have an alternative that already exists, even if it is not generally considered as a mechanism for supporting creative work.

The charitable contribution tax deduction is a way the government supports a wide variety of non-profit organizations. In many cases, such as orchestras, operas, art and culture programs, these contributions support people doing creative work. As it stands of course, the vast majority of these deductions are not for creative work, and the bulk of the benefit goes to high income people who both itemize on their tax returns and also are in the top marginal income bracket, which means the deduction would be worth more.

However, the charitable contribution tax deduction can serve as useful model. Instead of having a tax deduction, we could create a tax credit, say $100 to $200 per person. And, we could stipulate that the credit can only be used to support creative workers or organizations that support creative work. The latter could be organizations that commit themselves to supporting say, mystery writers or country music singers, which would serve as intermediaries for people who don’t want to use their credit for supporting specific individuals.

To be eligible to receive the funding, a person or organization would have to register in the same way that an organization has to register now with the I.R.S. to get tax exempt status. This would mean effectively saying what it is they do, as in write music, or play guitar. As is the case now, there would no effort to determine whether a particular individual or organization is good at what they do, just as the I.R.S. doesn’t try to determine if a church is a good church or a museum is a good museum. The only issue is preventing fraud, ensuring that they do what they claim to do. [3]

The other condition of eligibility is that workers would lose copyright protection for the time they are in the tax credit system and a substantial period (e.g. five years) afterwards. The point is that we only subsidize creative work once. If we pay the worker to produce a book or movie or song, we don’t have to pay them a second time by granting them a copyright monopoly.

The logic of having a ban on copyright protection for a period after being in the system is to avoid having people using the tax credit system as an effective farm system, where they develop a reputation and then join the copyright system. They would still have the option to change systems, but they would have to wait for a period of time.

A nice feature of this provision is that it is effectively self-enforcing. If a person breaks the rules and seeks to get a copyright for their work a year after they leave the tax credit system, they would find themselves unable to enforce the copyright. If they attempted to take legal action against someone for infringement, the defendant need only point to the fact that they had been registered in the tax credit system the prior year. Therefore, their copyright is not valid. (I discuss this system in somewhat more detail in chapter 5 of Rigged [it’s free].)

This sort of system could produce a vast amount of creative work that could be freely reproduced and transferred without any concerns about copyright. If AI programs wanted to scrape them to create new works, there would be no issue of compensation, the producers having already been compensated. A rule that could be applied (obviously this requires more thought) is some sort acknowledgement in an AI-produced work, much as any scholarly article includes a reference section for work that it draws on. This would prevent outright plagiarism by an AI program and also give credit to the creative workers who it relied upon for a derivative work. This is also something that presumably could be very easily programmed into any AI system.

I have heard people complain about the fact that this tax credit system would mean that creative workers would lose control over their work. For example, if some racist politician wanted to use their song at a campaign rally, they would have no way to stop them. This is true, but there are a couple of points worth keeping in mind.

First, even under the copyright system many creative workers sign over the rights to their work, so they already would not have the ability to prevent their work from being used in ways they found distasteful. Second, most people in society don’t have the ability to control what is done with their work. For example, jokes can’t be copyrighted. If someone writes a joke that a racist politician decided is the perfect line to start their campaign stump speech, there is nothing the joke writer can do about it, except complain. It’s hard to see why a musician or songwriter should have more right to control what is done with their work than a comedy writer.

Second, many people find their work used for purposes of which they strongly disapprove. Many of the physicists whose discoveries laid the groundwork for the development of the atomic bomb were pacifists. They were appalled that their work could be used to create a weapon of mass destruction. But there was nothing they could do about it. That seems a more serious complaint that a distasteful politician using a song without permission.

Copyright with a Tax Credit System

In principle, there is no reason that a tax credit system could not exist side by side with the copyright system. There could be many creative workers, which would likely include many well-established stars, who would opt to stay in the copyright system. In any case, there would still be a vast amount of material already protected by copyright.

As a general matter of principle, it is a good policy to respect property rights after they have been granted, even if it may have been a bad idea to grant those rights in the first place. For this reason, it would be appropriate to continue to respect existing copyrights. However, we can make an important change in the rules.

Copyright suits need not be eligible for statutory damages. If my neighbor knocks over my fence with their SUV, I can sue them for the cost of repairing my fence. I don’t also get statutory damages and usually would not be able to collect attorney fees. We don’t have to give this special status to those bringing lawsuits for copyright infringement.

This is likely to mean far fewer occasions for lawsuits for copyright infringement, which means fewer resources would be wasted contesting these suits and taking steps to prevent them. This could also make the copyright system less attractive relative to the tax credit system. If that turned out to be the case, that seems like a great outcome.

Time to Re-evaluate Copyright Monopolies, not AI

This is obviously a very superficial discussion of issues arising with AI. It also only a portion of the copyright related issues. For example, copyright also comes up with software and there are likely to be many instances where AI programs arguably infringe on copyrighted software.

However, the key point is that we should not treat our current rules on intellectual property as set in stone. When the Internet first became an important development in the 1990s, at the urging of the music industry, Congress rushed to pass the Digital Millennial Copyright Act, to ensure that copyrights would be enforced on the web. This limited the potential of the Internet as a means to freely transfer information, articles, books, music, and movies and other digital material.

Now we are hearing similar concerns about how AI will affect the value of copyrighted material. Rather than limiting AI, it might be more appropriate to reconsider copyright and determine whether it is still the best mechanism for supporting creative work. As I argue here, there are good reasons for thinking that is not the case.

[1] A provision in the Trans-Pacific Partnership would have required countries to have criminal penalties for copyright infringement.

[2] Note that the law with regard to copyright enforcement is the exact opposite of what it holds for third party content with regards to allegations of defamation. As a result of Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act, Facebook, Twitter and other Internet intermediaries can freely host defamatory material, and even profit from it directly when they sell ads, without any risk of legal consequences.

[3] It would be necessary to have rules to prevent simple scams. For example, in order to be able to receive the credit, there could be a requirement that a person gets at least $3,000. This would prevent any simple trading scheme where people exchange credits with each other. While it would still be possible have some pooling and kickbacks even with a $3,000 or similar size minimum, this would require a lot of work for relatively little money. Furthermore, it is much easier to organize a much larger kickback scheme with the current chartable deduction.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

• Federal ReserveInterest RatesUnited StatesEE. UU.

When Jerome Powell took over as chair of the Federal Reserve Board in January of 2018, the Fed had already been on a path of gradually hiking interest rates. They had moved away from the Great Recession zero rate in December of 2015 and had been hiking in quarter point increments at every other meeting. The Federal Funds rate stood at 1.25 percent when Powell took over from his predecessor Janet Yellen.

Powell continued with this path of rate hikes until the fall of 2018, and then he did something remarkable: he lowered rates. He had lowered rates by 0.75 percentage points by the time the pandemic hit in 2020.

This reversal was remarkable because it went very much against the conventional wisdom at the Fed and the economics profession as a whole. The unemployment rate at the time was well under 4.0 percent, a level that most economists argued would lead to higher inflation.

However, Powell pointed out that there was no serious evidence of inflationary pressures in the economy at the time. He also noted the enormous benefits of low unemployment. As many of us had long argued, Powell pointed to the fact that the biggest beneficiaries from low unemployment were the people who were most disadvantaged in the labor.

A 1.0 percentage point drop in the unemployment rate generally meant a drop of 1.5 percentage points for Hispanic workers and 2.0 percent for Black workers. The decline was even larger for Black teens. Workers with less education saw the biggest increase in their job prospects. And, in a tight labor market, employers seek out workers with disabilities and even those with criminal records.

In short, there are huge benefits to pushing the unemployment rate as low as possible, and Powell happily pointed to these benefits as he lowered interest rates even in an environment where the economy was already operating at full employment by standard estimates. Powell was willing to put aside the Fed’s obsession with fighting inflation, even when it wasn’t there.

This was the reason that many progressives, including me, wanted President Biden to reappoint Powell. While Lael Brainard, who was then a Fed governor, would have also been an outstanding pick, as a Republican, Powell’s reappointment faced far fewer political obstacles. There was no risk that one of our “centrist” showboat senators (Manchin and Sinema) might seize on some real or imagined slight and block the nomination.

Powell was also likely to have more leeway as a second term chair in pursuing a dovish interest rate policy. Fed chair is a position where seniority matters a lot, as can be seen by the Greenspan worship that stemmed largely from his long service as Fed chair. Although Brainard was a highly respected economist, she might have a harder time staying the course if the business press pushed for higher rates.

Powell’s Pandemic Policy

Powell did pursue a dovish policy, acting aggressively to support the economy during the pandemic with both a zero federal funds rate, and also extensive quantitative easing that pushed the 10-year Treasury bond rate to under 1.0 percent in the summer of 2020. Low rates helped to spur construction and allowed tens of millions of people to refinance mortgages, saving thousands of dollars a year on interest rates.

As virtually everyone (including me) would now agree, he kept these expansionary policies in place for too long. While Fed policy was not the major factor in the pandemic inflation, it did play a role, especially in the housing market. While most of the rise in house prices and rents was driven by fundamentals in the market (unlike in the bubble years from 2002-2007), there was clearly a speculative element towards the end of 2021 and the start of 2022.

This became evident when the Fed first raised rates in March of 2022. Even though the initial hike was just 0.25 percentage points, the housing market changed almost immediately. Prior to the hike, almost every house immediately got multiple above listing offers. After the hike, many houses received no offers and it became standard for buyers to offer prices well below the asking price.

Given this outcome, it would have been good if the Fed had made this move several months sooner. Speculative runups in house prices are not good news for the economy in general, even if there may be a small number of lucky sellers who might hit the peak of the market.

Anyhow, after having waited too long to raise rates, Powell felt the need to re-establish his status as a determined inflation fighter. He embarked on a series of aggressive three-quarter point rate hikes and repeatedly appealed to the ghost of Paul Volcker.

Powell went farther and faster than many of us felt was warranted. It will take time to see the full effect of past rate hikes on the economy. The rapid rise in rates did create stresses in the banking system, although the failures of the Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) and Signature Bank seem to be largely due to incredibly inept management, coupled with major regulatory failures at the Fed.

While bank failures are always fun, the more important issue is what happens to the real economy. At this point it seems the economy faces greater risk on the downside, with unemployment rising, than with inflation reversing its current downward path.

There has been a clear hit to credit availability as a result of banks tightening standards following the SVB panic. Higher rates are also having their expected effect on loan availability. Housing starts have slowed sharply, although residential construction remains strong due to a large backlog of unfinished homes resulting from supply chain problems during the pandemic.

Higher rates have also put an end to the flood of housing refinancing that helped to support consumption growth through the pandemic. And, non-residential investment has also slowed sharply in recent months.

For these reasons, there are real grounds for expecting a growth slowdown and a resulting rise in the unemployment rate. The other side of the story is that it looks as the Fed has won its war on inflation.

I’ll admit to having been an inflation dove all along, but the facts speak for themselves. We know that housing inflation will slow sharply in the months ahead based on private indexes of marketed housing units. These indexes have been showing much lower inflation, and even deflation, since the late summer. They lead the CPI rental indexes by 6-12 months.

We got the first clear evidence of lower inflation in the CPI rental indexes with the March release, with both rent indexes rising just 0.5 percent, after rising at more than a 9.0 percent annual rate in the prior three months. The CPI rent indexes are virtually certain to show further declines over the course of the year, with rental inflation likely falling below its pre-pandemic pace.

Much has been made of the big bad news items in the March CPI, the 0.4 percent rise in new vehicle prices. This is certainly bad news for the immediate inflation picture as it seems that supply chain problems continue to limit the production of new cars and trucks.

But this is not a long-term inflation issue. We have not forgotten how to build cars and trucks. This is a story where the chip shortage, resulting from a fire at a major semi-conductor factory in Japan, has proved to be more enduring that many had expected. That hardly seems like a good reason to be raising interest rates and throwing people out of work.

The picture for many non-housing services was also positive. In particular, the medical services index fell 0.5 percent in March after dropping 0.7 percent in each of the prior two months. Some of this decline is due to the peculiarities of the way health insurance costs are measured in the CPI, but it is pretty hard to tell a story of excessive inflation in this key sector of the economy.

The March Producer Price Index showed even better news about inflationary pressures at earlier stages of production. The overall final demand index fell by 0.5 percent in March, while the index for final demand for services dropped by 0.3 percent. While there are areas where there seem to be price pressures, the overwhelming picture in this release is one of sharply lower inflation, or even deflation. Clearly higher inflation will not be driven by price pressures at the wholesale level.

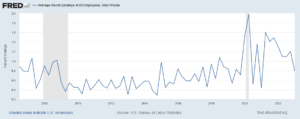

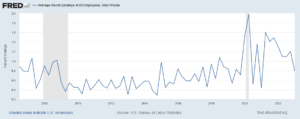

Perhaps most importantly, the pace of wage growth has slowed sharply. The annualized rate of growth in the average hourly wage over the last three months is just 3.2 percent, down from a 6.0 percent pace at the start of 2022. This is lower than the pace of wage growth in 2018 and 2019, when inflation was below the Fed’s 2.0 percent target. It is very difficult to tell a story where wage growth is under 4.0 percent, and inflation is still much above the Fed’s target.

Can Powell Change Course Again?

This raises the question as to whether Powell will again follow the path he took in 2019 and reverse course when the data indicate it is appropriate? There is still much uncertainty about the course of the economy at this point. We don’t know the full effect of the fallout from the SVB failure and it’s not clear how much of the impact of past Fed rate hikes is yet to be felt.

That makes a strong argument for a pause at the Fed’s meeting next month, which will come before we get any data from April. However, if we continue to see evidence of economic weakness, as well as slowing inflation, the Fed needs to be prepared to start lowering rates.

Powell was quite vocal in recognizing the Fed’s twin mandate for full employment, as well as price stability, when he lowered rates in 2019. There is no virtue in going overboard in the effort to fight inflation. If the data show that the war on inflation has been won, and we see the prospect of a weakening economy with higher unemployment, it needs to shift course.

Powell went in the right direction four years ago when he bucked the conventional wisdom and lowered rates in 2019. He needs to be prepared to do that again this year.

When Jerome Powell took over as chair of the Federal Reserve Board in January of 2018, the Fed had already been on a path of gradually hiking interest rates. They had moved away from the Great Recession zero rate in December of 2015 and had been hiking in quarter point increments at every other meeting. The Federal Funds rate stood at 1.25 percent when Powell took over from his predecessor Janet Yellen.

Powell continued with this path of rate hikes until the fall of 2018, and then he did something remarkable: he lowered rates. He had lowered rates by 0.75 percentage points by the time the pandemic hit in 2020.

This reversal was remarkable because it went very much against the conventional wisdom at the Fed and the economics profession as a whole. The unemployment rate at the time was well under 4.0 percent, a level that most economists argued would lead to higher inflation.

However, Powell pointed out that there was no serious evidence of inflationary pressures in the economy at the time. He also noted the enormous benefits of low unemployment. As many of us had long argued, Powell pointed to the fact that the biggest beneficiaries from low unemployment were the people who were most disadvantaged in the labor.

A 1.0 percentage point drop in the unemployment rate generally meant a drop of 1.5 percentage points for Hispanic workers and 2.0 percent for Black workers. The decline was even larger for Black teens. Workers with less education saw the biggest increase in their job prospects. And, in a tight labor market, employers seek out workers with disabilities and even those with criminal records.

In short, there are huge benefits to pushing the unemployment rate as low as possible, and Powell happily pointed to these benefits as he lowered interest rates even in an environment where the economy was already operating at full employment by standard estimates. Powell was willing to put aside the Fed’s obsession with fighting inflation, even when it wasn’t there.

This was the reason that many progressives, including me, wanted President Biden to reappoint Powell. While Lael Brainard, who was then a Fed governor, would have also been an outstanding pick, as a Republican, Powell’s reappointment faced far fewer political obstacles. There was no risk that one of our “centrist” showboat senators (Manchin and Sinema) might seize on some real or imagined slight and block the nomination.

Powell was also likely to have more leeway as a second term chair in pursuing a dovish interest rate policy. Fed chair is a position where seniority matters a lot, as can be seen by the Greenspan worship that stemmed largely from his long service as Fed chair. Although Brainard was a highly respected economist, she might have a harder time staying the course if the business press pushed for higher rates.

Powell’s Pandemic Policy