May 19, 2015

Dean Baker

Mother Jones, May 19, 2015

View article at original source.

The main point of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) was to extend health insurance coverage to the uninsured. While this is a tremendously important goal, a benefit that is almost equally important was to provide a guarantee of coverage to those already insured if they lose or leave their job. This matters hugely because roughly 2 million people lose their job every month due to firing or layoffs. As a result of the ACA, most of these workers can now count on being able to get affordable coverage even after losing their job.

The ACA also means that people who may previously have felt trapped at a job because of their need for insurance now can leave their job without the risk that they or their family would go uninsured. This could give many pre-Medicare age workers the option to retire early. It could give workers with young children or other care-giving responsibilities the opportunity to work part-time. It could give workers the opportunity to start a business. Or, it could just give workers the opportunity to leave a job they hate.

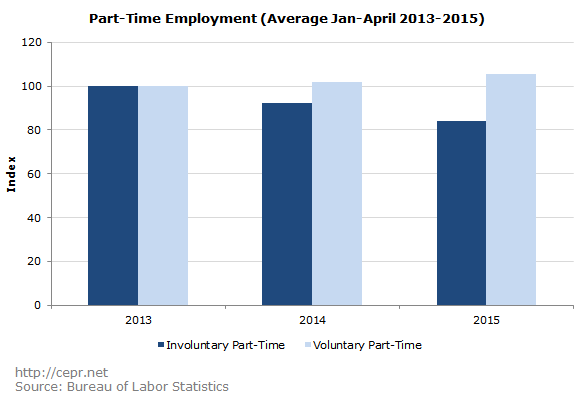

While it is still too early to reach conclusive assessments of the labor market impact of the ACA, the evidence to date looks promising. Republican opponents of Obamacare have often complained that the program would turn the country into a “part-time nation.” It turns out that there is something to their story, but probably not what they intended. The number of people who are working part-time for economic reasons, meaning they would work full-time if a full-time position was available, has fallen by almost 16 percent from the start of 2013 to the start of 2015. This is part of the general improvement in the labor market over this period.

The number of people working part-time involuntarily is still well above pre-recession levels, but it has been going in the right direction.

It is true that the employer sanction part of the ACA has not taken effect (which required that employers with more than 50 workers provide insurance or pay a penalty, but it is not clear this would make a difference. Under the original wording of the law (Obama subsequently suspended this provision), employers would have expected that the sanctions would apply for the first six months of 2013. We found no evidence of shifting to more part-time work during this period compared to the first six months of 2012.

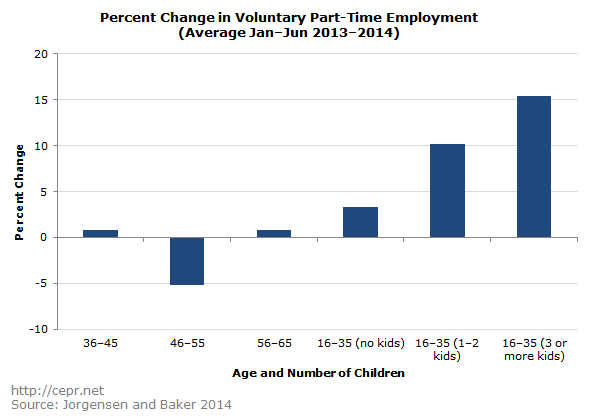

But there is a story on increased voluntary part-time employment. This is up by 5.7 percent in the first four months of 2015 compared to 2013. This corresponds to more than 1 million people who have chosen to work part-time. We did some analysis of who these people were and found that it was overwhelmingly a story of young parents working part-time.

There was little change or an actual decline in the percentage of workers over the age of 35 who were working part-time voluntarily. There was a modest increase in the percentage of workers under age 35, without children, working part-time voluntarily. There was a 10.2 percent increase in the share of workers under the age of 35, with 1–2 kids, working part-time. For young workers with three of more kids, the increase was 15.4 percent.

Based on these findings it appears that Obamacare has allowed many young parents the opportunity to work at part-time jobs so that they could spend more time with their kids. Back in the old days we might have thought this was an outcome that family-values conservatives would have welcomed.

As far as other labor market effects of Obamacare, there has been a modest uptick in self-employment, but it would require more analysis to give the ACA credit. Similarly, older workers are accounting for a smaller share of employment growth, perhaps due to the fact that they no longer to need to get health care through their jobs. These areas will require further study to make any conclusive judgments, but based on the data we have seen to date, it seems pretty clear that Obamacare is allowing many young parents to have more time with their kids. And that is a good story that needs to be told.