The authors thank Michael Galant, Jake Johnston, David Rosnick, and Mark Weisbrot for valuable input and feedback.

This is a version of a forthcoming journal article submitted to Development.

Ivana Vasic-Lalovic is a research associate at the Center for Economic and Policy Research. Her work focuses on issues in sustainable development and the international financial architecture. She holds an MPA from Columbia University’s School of International and Public Affairs and a BA in international relations from the University of Pennsylvania.

Dr. Andrés Arauz is a senior research fellow at the Center for Economic and Policy Research. His work focuses on payment systems and their regulation, banking, balance of payments, and public economics. He has ample policy experience in development planning, public finance, central banking, tax, debt, trade, investment, and industrial policy. Arauz holds a PhD in financial economics from the National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM), a master’s degree from the Latin American Faculty of Social Sciences (FLACSO) Ecuador, and a BSc from the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor.

Francisco Amsler is an economics consultant and researcher and a former international program intern at the Center for Economic and Policy Research. His work focuses on macroeconomic policy and modeling, climate finance, and sustainable development in developing countries. A former Erasmus Mundus scholar, he holds a double master’s degree in economic analysis and policy from the University Paris Cité (France) and Roma Tre University (Italy) and a bachelor’s degree in Economics from the National University of the Litoral (Argentina).

Abstract

This paper argues for the elimination of the surcharge policy of the International Monetary Fund (IMF). It explores the legal history of surcharges and underscores that there are precedents (i.e., in 1974, 1981, and 1992) for their complete removal. The paper also shows that surcharges are a burden on indebted countries and that the Fund’s official arguments for retaining them do not hold.

Key words: sovereign debt, developing countries, multilateral loans, perverse incentives

This contribution is free from any conflicts of interest, including all financial and non-financial interests and relationships.

Given its important role in the global safety net, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) must realign its policies to meet global challenges. The removal of surcharges is a necessary step in the right direction.

The IMF serves as a creditor to prevent or respond to balance of payments crises. Under certain conditions, the IMF applies surcharges, i.e., a higher rate of charge, that add 200-300 basis points to the annual interest on the loans of its most indebted borrowers under the credit facilities of the General Resources Account (GRA), totalling nearly $2 billion in added payments on IMF loans in 2023.1 These higher rates can be seen as punitive, as they increase the debt burdens of countries at a time of great vulnerability. In the context of multiple, interconnected global crises, from the catastrophic consequences of climate change to debt distress and development failures, the imposition of surcharges is likely to grow in both size and breadth, exacerbating their negative effects.

Global public debt has reached unprecedented levels, increasing vulnerability to external shocks and the share of revenue allocated to interest payments.2 The debt dynamics triggered by the COVID-19 pandemic were compounded by increasing interest rates in advanced economies, followed by rising rates worldwide, low economic growth prospects in developing countries, and heightened global uncertainty.3 By diverting an increasing amount of public resources from health, education, and climate action, the debt burden is becoming a direct obstacle to promoting sustainable development in the Global South.4 The lack of comprehensive institutional mechanisms for effective and timely debt relief and restructuring underscores these concerns.

In this context, several international organizations, civil society organizations and governments of the Global South have called for a reform of the global financial architecture and its governance to adapt to the needs of global development.5 Many of these calls for comprehensive reform have specifically called for the discontinuation of the IMF’s surcharge policy.

This paper presents a historical overview of this policy and argues for its elimination. Relying on data published by the IMF and calculations made by the Center for Economic and Policy Research (CEPR), the paper discusses the growing burden of surcharges and their negative implications given the multiple crises facing developing countries today. It argues that surcharges are ineffective in achieving their purported goals, are characterized by perverse incentives, and are unjustified from both an economic perspective and a legal perspective. By continuing them, the IMF harms those whom it is supposed to help, worsening the consequences of the concurrent debt, development, and climate crises. This paper further demonstrates precedents for the suspension of surcharges, and it underscores the opportunity for the IMF to eliminate them during its current review of the policy.

The IMF has subjected borrowing countries to surcharges on top of regular interest payments in various forms and for several decades, with problematic results that even the IMF has acknowledged. The policy can be traced back to the historical use of graduated charges in IMF lending. From 1945 to 1974, instead of a standard rate of charge such as the one in use today, the Fund employed a system of graduated size- and time-based charges, meaning that countries borrowed at a rate that grew with larger and longer borrowing.6 This configuration purportedly served to “encourage the temporary use of Fund resources,” a justification that would be repeated and debunked with each iteration of this system of charges that eventually gave rise to the current surcharge policy.

In a 2000 review of the Fund’s facilities, IMF staff noted in hindsight that instead of discouraging larger and longer borrowing, the policy of graduated charges resulted in “perverse incentives”:7

Beyond the problem of complexity, this attribution method tended to work against the objective of discouraging large or long use of Fund resources: the system of charges presented members with only a small incentive to repurchase early (as the most costly segments could be extinguished only by eliminating all Fund credit outstanding) or to forgo additional purchases (as the new segments were always the least costly).

While size-based charges were eliminated in favor of a flat rate in 1974, time-based charges were maintained until 1981, and they were referred to as “surcharges.” During the 1970s, the system became “unwieldy and nontransparent” due to the creation of new facilities and funding sources,8 and the remaining time-based surcharge was eliminated, creating a single rate of charge in 1981.9

Five years later, surcharges were reintroduced in a different framework but with a similar line of reasoning. The IMF applied surcharges (called “special charges” at the time) on the interest rate on overdue balances in February 1986, when several developing countries entered arrears and struggled to repay their loans in the wake of the Volcker Shock.10 According to the official IMF historian, instead of incentivizing repayment, surcharges became a “significant factor causing each country’s arrears to rise rapidly.”11 Over the following five years, the Fund collected only $55 million in surcharges of the over $300 million that it charged to 38 countries. As a result, in 1992, the practice was suspended for all outstanding cases; however, special charges on new arrangements continued to be applied.

In 1997, the IMF reinstituted surcharges on countries borrowing from the newly created Supplemental Reserve Facility (SRF), which became the basis for the current application of surcharges. The SRF was created in response to the Asian financial crisis for countries with “exceptional balance of payments difficulties” due to sudden stops in capital inflows.12 The facility provided short-term loans above normal access limits at higher-than-market rates to encourage borrowers to return to market lenders. The terms included a surcharge of up to 500 basis points on top of regular interest charges, depending on the length of time it took for a country to regularly repay its obligation. Instead of penalizing borrowing into arrears, these surcharges were applied on debt that was not overdue, mirroring the original system of time-based surcharges eliminated in 1981.

The stated aims of the policy were to disincentivize reliance on the SRF, encourage speedy repayment, and increase revenue to support the IMF’s capital base. However, detractors of the practice in the IMF’s Executive Board of Directors at the time noted that “A substantial surcharge…might not be compatible with the cooperative nature of the Fund and, by adding to members’ balance of payments difficulties, could prove counterproductive.”13 The growing burden of surcharges in the following decades has proven this to be the case.

In the 2000s, the IMF expanded the surcharge policy, standardizing it across all GRA facilities in 2009.14 The Fund, however, maintained an opaque information policy and failed to publish15 regular, comprehensive data on surcharges for the next fourteen years. The policy did not enter public discourse, and until recently, little to no academic research explored the contemporary impact of surcharges.

In the context of the extensive and continued social and economic consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic, critical research on the policy gained traction among civil society groups and in academia.

Arauz et al.16 and Munevar17 present extensive calculated estimates of surcharges, discussing the harmful effects of the procyclical measure and calling for its elimination. Manzanelli18 provides an estimate of Argentina’s surcharges in the context of record-breaking borrowing from the IMF. Stiglitz and Gallagher19 similarly argue against surcharges, highlighting their “regressive” and “counterproductive” transfer of resources from middle-income countries. Ghosh20 posits that surcharges exhibit “incentive incompatibility” between the stated goals of the policy and its application and represent a failure in the management of the IMF.

The surcharge policy has also raised legal and human rights concerns. Citing international human rights law, a group of independent experts and special rapporteurs at the United Nations expresses

grave concerns about the differentiated impact of the IMF’s surcharge policy on the ability of low- and middle-income countries to comply with their international obligations to progressively realize the human rights of their populations in key areas such as health, education and social protection.21

The group further cites the disproportionate harm of the policy to women and girls, concluding that it “contravenes [the] IMF’s own proposal of a gender mainstreaming strategy.” Additionally, Laskaridis22 discusses the role of surcharges in exacerbating gender inequality and the impacts of economic crisis on women’s labor, childcare costs, and sanitation, among other issues.

Similarly, Bohoslavsky et al.23 argue that surcharges “are regressive in terms of human rights, including the right to development, as they redirect scarce fiscal resources in favor of payment to a solvent creditor.” Arauz et al.24 presents another legal argument, concluding that surcharges violate the IMF Articles of Agreement, specifically Article 1, which states that IMF lending cannot be “destructive of national or international prosperity.”

The policy also found opponents in the US Congress, who urged Secretary of the Treasury Janet Yellen to endorse its elimination.25 Multiple bills and amendments introduced in both chambers, including an amendment that passed the House of Representatives, sought for the IMF to conduct a comprehensive review of the efficacy and impacts of surcharges; during such a review, surcharges would be suspended. These bills and amendments also called for the Fund to publish country-level data on the amounts charged.26272829

After sustained pressure from civil society groups and members of the US Congress for greater transparency, the IMF began releasing comprehensive historical data and partial estimates of future surcharge payments in the summer of 2023.30 Although the release of such data is a welcome step, the figures grossly underestimate the actual amounts that borrowing countries will owe on top of their interest and principal. The IMF estimates future surcharge payments using only loan amounts that have been disbursed, leaving out surcharges to be applied on scheduled future disbursements. Therefore, researchers continue to calculate more accurate estimates according to information provided in each borrowing country’s IMF Staff Report.3132 In the following section, this paper provides current estimates per country for the next ten years based on CEPR calculations.33

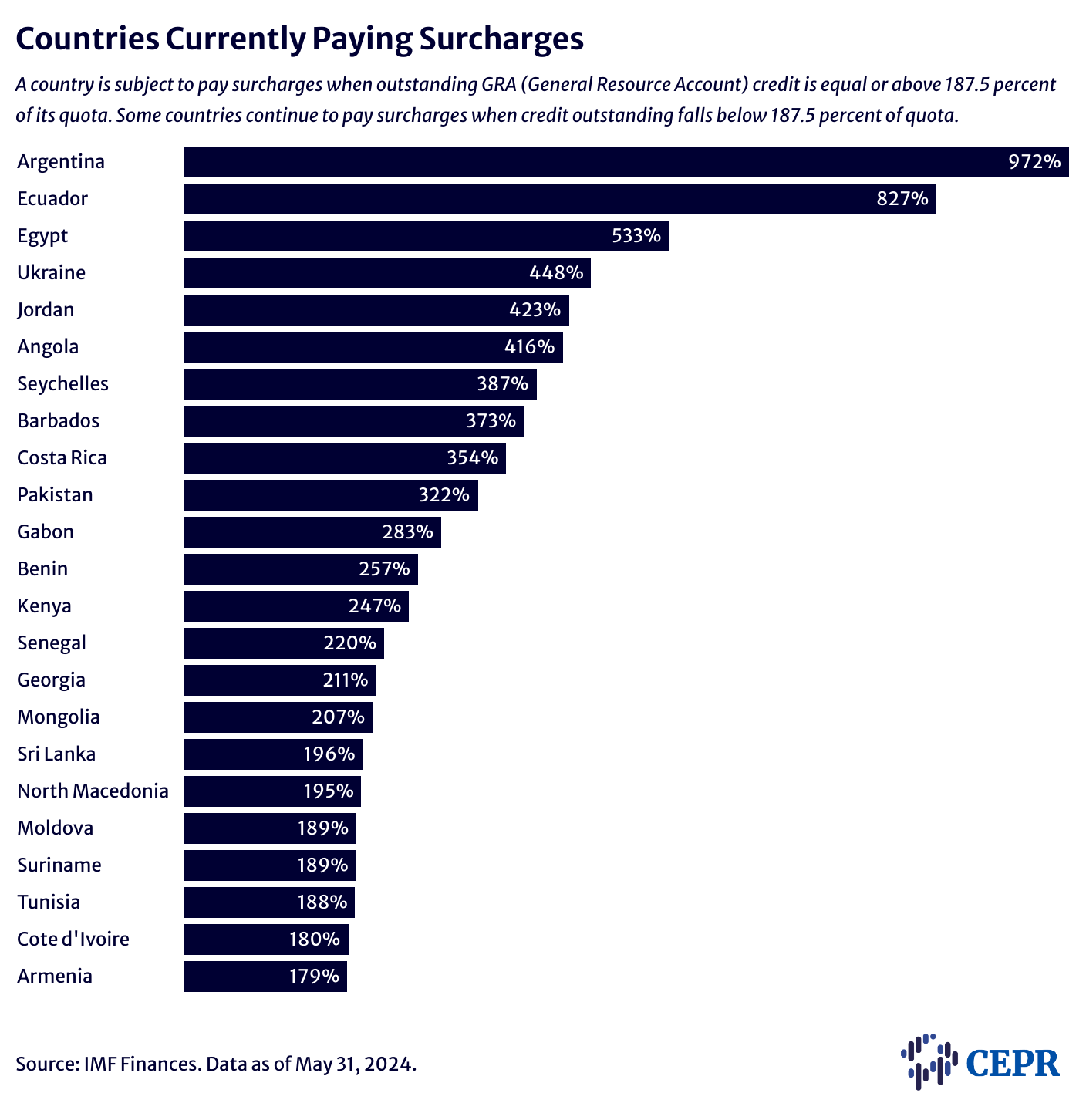

Since the standardization of the surcharge policy across all GRA lending in 2009, 41 countries have been subject to surcharges.34 Largely due to external shocks such as the COVID-19 pandemic, monetary tightening in advanced economies, and increasing climate impacts, the number of countries paying surcharges annually has nearly tripled over the past five years, from eight in 2019 to 23 in 2024. Figure 1 below illustrates surcharge-paying countries as of May 2024. Seven countries are also at risk of paying surcharges in the future as their IMF debt burdens increase.35

Figure 1

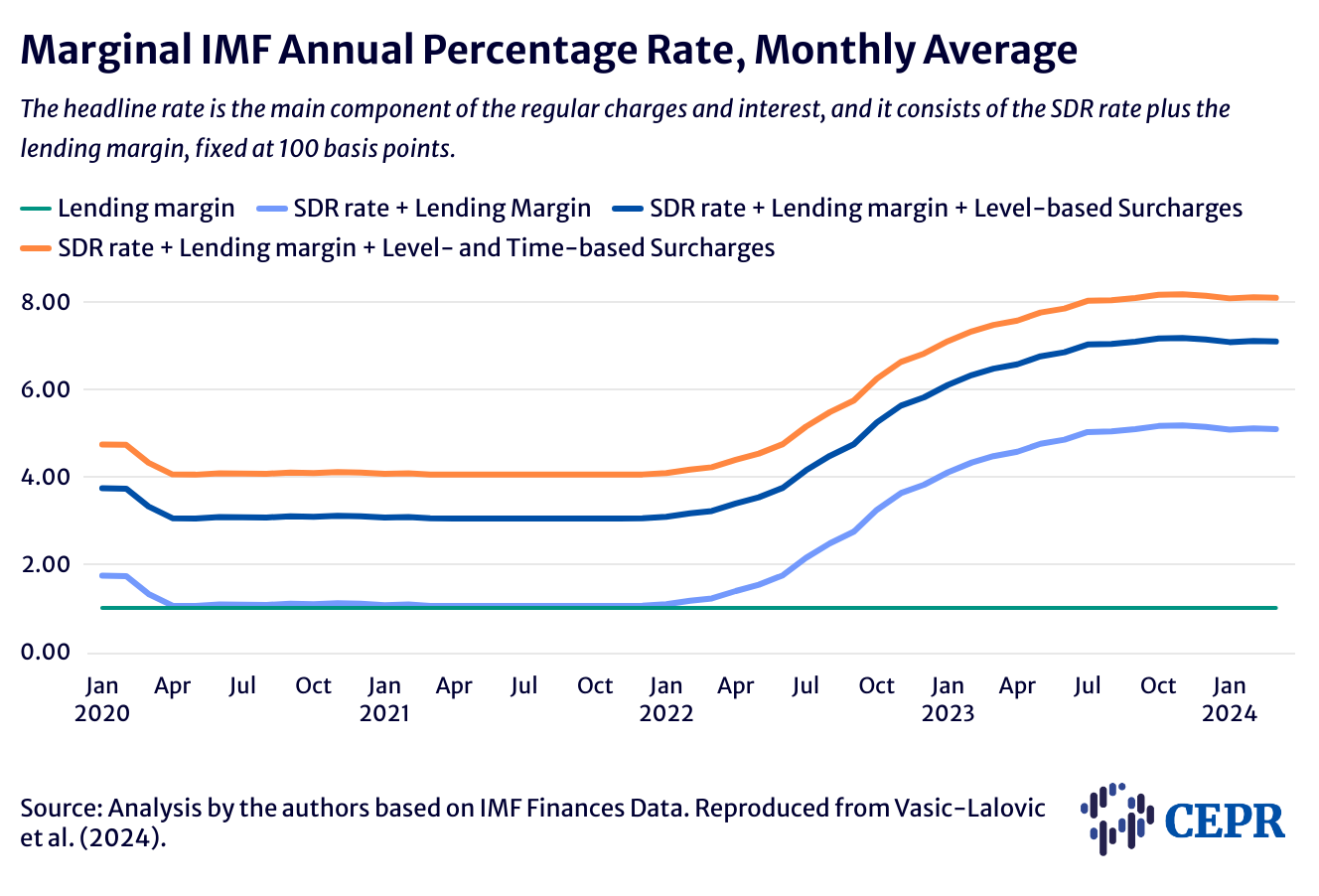

The current application of the policy includes a size- or “level-based” surcharge applied to the magnitude of the outstanding loans and a “time-based” surcharge applied to the length of time it takes to repay. Borrowers begin paying 200 basis points in level-based surcharges when their outstanding credit to the IMF reaches 187.5 percent of their quota.36 A time-based surcharge of 100 basis points is applied when borrowing from a facility exceeds three years (51 months for an Extended Fund Facility arrangement). When added to the IMF’s lending and special drawing right (SDR) rate, this effectively means that some countries pay up to 8 percent in interest on their IMF debt, which is a significant increase to the cost of borrowing from the Fund,37 as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2

Surcharges add to an already heightened cost of borrowing from most creditors, including the IMF, which increased its rates following monetary tightening in the advanced economies whose currencies comprise the SDR basket. The IMF tries to justify this high rate by comparing its lending to implicit rates derived from bond market yields.38 However, it is empirically incorrect to assume that a country could access unsecured funding from capital markets while engaged in a deep relationship with a super senior creditor and debt market gatekeeper such as the IMF.

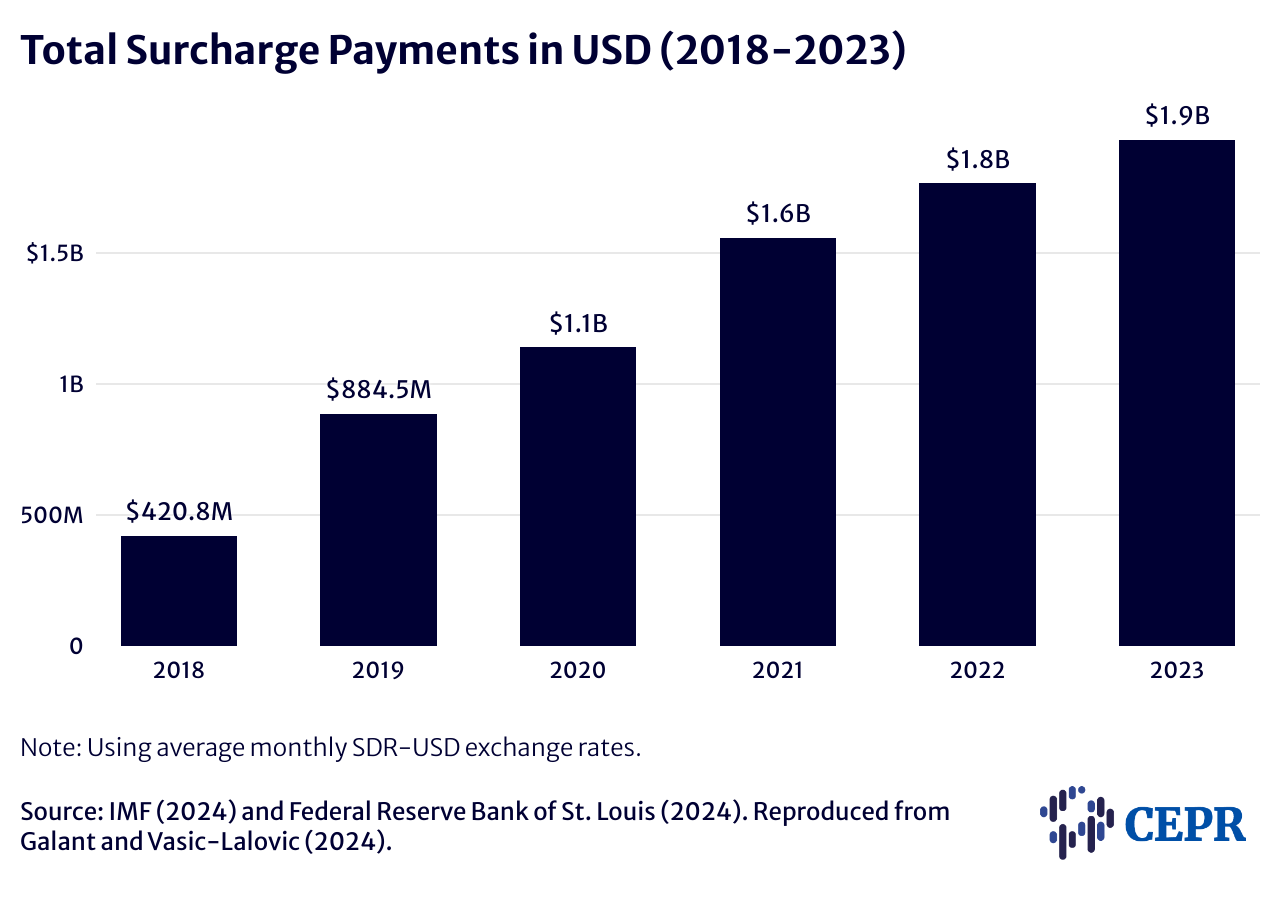

As a greater number of countries owe increasing amounts of surcharges, annual total payments have quadrupled since 2018, as shown in Figure 3. Over the past six years, the IMF charged $7 billion in surcharges.

Figure 3

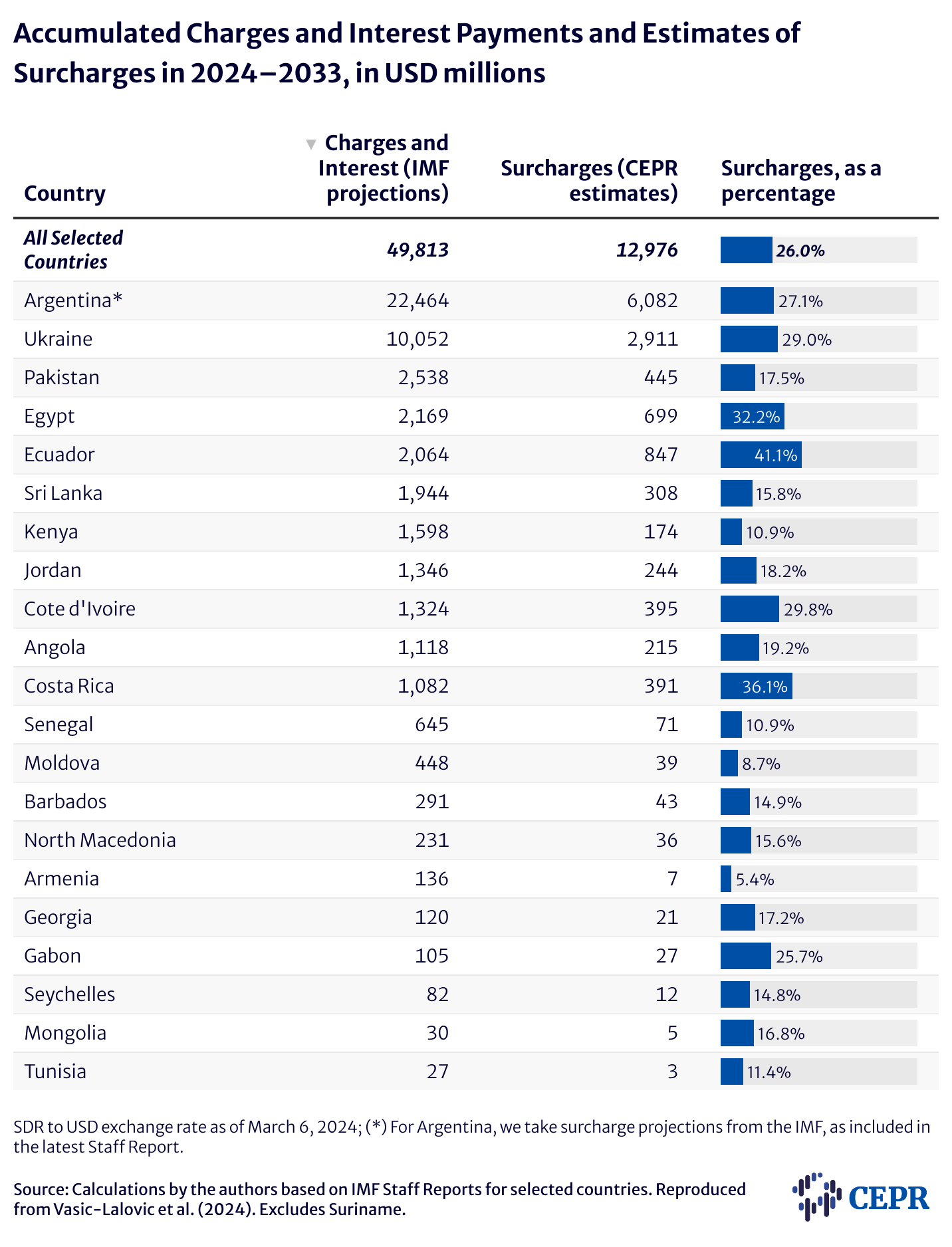

Through 2033, CEPR estimates that the IMF will charge approximately $13 billion in surcharges, as shown in Figure 4. Argentina alone will owe an estimated $6 billion, followed by Ukraine, with a debt of nearly $3 billion. On average, surcharges will represent 26 percent of all charges and interest levied on surcharge-paying countries. For some borrowers, such as Costa Rica and Ecuador, surcharges will represent 36 and 41 percent of their total charges and interest on IMF borrowing, respectively.

Figure 4

The evolution of surcharge obligations over time suggests that this policy is not a temporary measure for incentivizing countries to make early repayments. Rather, it is an additional burden on affected countries that is likely to grow and persist over time. Thus, for countries, it is an additional obstacle to recovering from crises.

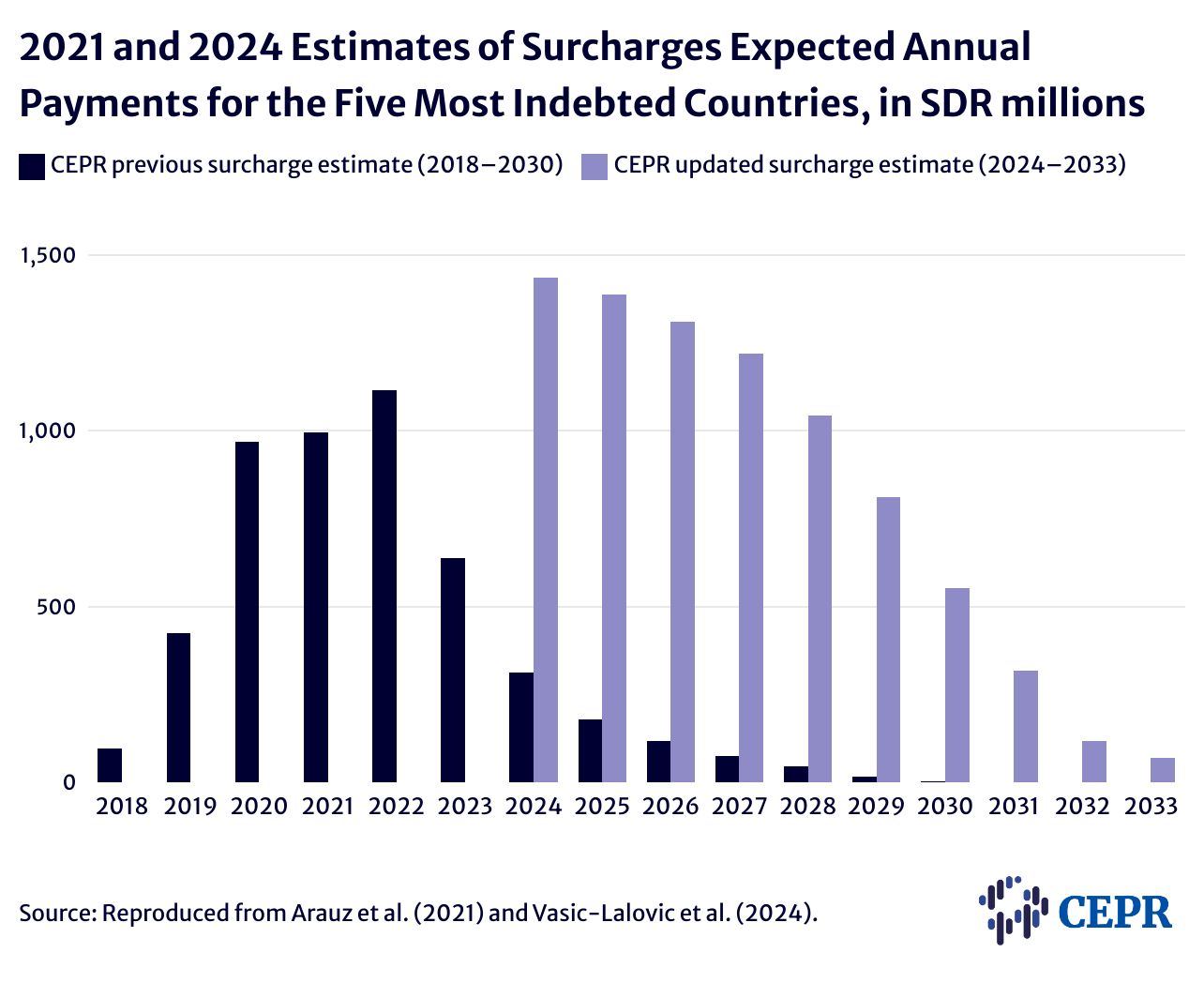

Figure 5

Figure 5 compares CEPR’s projections of surcharge payments from 2021 and 2024, which include both existing and prospective Fund lending at the time of measurement for the same set of countries. The difference between the estimates reflects the change in the amount of surcharges that the institution expected to collect three years ago versus what it currently expects to collect from the same five largest borrowers (i.e., Argentina, Ecuador, Egypt, Pakistan, and Ukraine) in terms of their credit-to-quota ratio.

In 2021, the five most indebted countries were expected to pay surcharges through 2030, with a peak in 2022 and declining payments thereafter. However, based on current projections, not only are these countries expected to make systematically larger surcharge payments, but their additional debt service burden to the IMF is also extended over a longer period. This increase and extension is an indication of the ineffectiveness of the surcharge policy in encouraging rapid repayment. That is, surcharges are actually increasing the debt burden for middle-income countries that are facing the most acute balance of payments problems.

As predominantly middle-income countries in an unfair international financial architecture, surcharge-paying countries face unique macroeconomic and fiscal challenges. Highly indebted middle-income countries tend to face harsher borrowing terms than their low-income counterparts, and they have few options for comprehensive debt resolution.39 Because they are largely ineligible for concessional financing like their low-income counterparts, middle-income countries mostly borrow from private creditors, which charge higher rates and have shorter maturities on repayment. Unlike wealthy countries, middle-income countries do not have access to swap lines in times of crisis. Like most developing countries, they are vulnerable to external shocks, such as the US Federal Reserve’s interest rate hikes from 2022, which caused central banks worldwide and multilateral lenders such as the IMF to follow suit.

All of these factors significantly increase the debt burdens of surcharge-paying countries. In fact, more than half of all surcharge-paying countries (i.e., 13) are currently in or at risk of debt distress, meaning that they are unable to meet financial obligations or are at risk thereof.40 In this context, the surcharge policy punishes highly-indebted countries at their most vulnerable state, when they are approaching or facing crisis and have reached the point of turning to the so-called lender of last resort.

By exacerbating existing debt challenges, surcharges cut into foreign currency reserves and reduce states’ ability to pay for crucial imports such as food and medicine. Increased debt burdens present a direct obstacle to financing basic public services and long-term public investments for development and climate preparedness.41 Ukraine, for example, will owe more in surcharges than it needs to rebuild its emergency response and civilian protection capacities.42 Furthermore, 11 surcharge-paying countries are highly climate vulnerable.43 In the context of the climate crisis, developing countries could utilize scarce resources for adaptation and disaster preparedness instead of being forced to deliver them to creditors, thereby increasing their vulnerability.

In today’s context, the IMF’s surcharge policy is anachronistic, fails to fulfill its stated purpose, and aggravates the precarious economic and balance of payments situations in indebted countries. When the current policy was instituted in 1997, the targeted borrowing countries had characteristics and macroeconomic conditions that were very different from those of the borrowers subject to surcharges today. The countries affected by the Asian financial crisis generally faced a liquidity problem caused by a sudden stop in short-term capital inflows. They were mainly export-led economies with strong balance of payments positions.44 Furthermore, they were not recovering from a catastrophic global pandemic, and the climate crisis in 1997 was not yet as consequential or costly as it is today.

Today, highly indebted surcharge-paying countries face structural balance of payments issues and have histories of defaults. For these countries, engulfed in simultaneous debt, development, and climate crises, sustainable recovery requires an overhaul of the international financial architecture, not punitive rates. The IMF’s surcharge policy substantially increases already unsustainable debt burdens, and it lessens the prospects for recovery.

Furthermore, surcharges create a set of perverse incentives, i.e., “incentive incompatibility” between the stated objectives of the policy and its implementation.4546 The IMF’s main rationale for surcharges is to incentivize borrowers to service obligations ahead of schedule and to discourage reliance on the Fund. The Fund also uses surcharges as a source of income, and it claims to rely on surcharge revenue to maintain precautionary balances, i.e., its capital base. In practice, however, the IMF incentivizes countries to seek large loans but penalizes them for doing so while generating revenue for itself.

There is little evidence to support faster repayment and lower borrowing amounts among the highest surcharge-paying countries. This fact is demonstrated by a pattern in which the top five surcharge-paying countries repeatedly refinance47 IMF loans nearing maturity with new IMF programs, thereby extending repayment and continuing to owe surcharges for years to come. In this sense, the Fund operates more like a commercial bank that is more interested in accumulating income through longer maturities than in customers paying off their credit card debt quickly. The policy features an additional perverse incentive: surcharges act as a penalty rate for borrowers even though they have not incurred a penalty. In other words, it is illogical that the IMF applies punitive measures on large borrowing that it approves and controls.

Moreover, the IMF does not require surcharges as a source of revenue. It already reached its target for precautionary balances in April 2024.48 According to its own estimates, even if surcharges are completely eliminated, the Fund would remain above target in future years.49 Furthermore, the Fund holds significant and undervalued gold reserves, which, if accounted for properly, obviate the need for additional revenue sources.50 As of April 2023, the IMF had $179 billion worth of gold (at $1,983 per ounce) that is still recorded and valued at 1960s prices (35 SDR per ounce), according to the IMF’s latest annual financial statements.51 Additionally, the gold would not need to be sold to increase precautionary balances, averting potential legal issues. Simply accounting for even a small portion of the reserves according to market prices would suffice to boost the Fund’s balance sheet.

The same argument can be made against using surcharges to subsidize the Poverty Relief and Growth Trust (PRGT, an IMF-managed trust fund for concessional loans to low-income countries currently subsidized by donations from rich countries) — an idea reportedly gaining support in the US government and other advanced economies.52 Linking GRA income, which itself is derived from surcharges, to the PRGT would effectively make much-needed concessional finance for low-income countries dependent on taxing highly indebted and crisis-prone middle-income countries. Not only would this linkage be harmful for surcharge-paying countries, but it would also create additional risks for PRGT recipients, particularly when other sources of funding, including contributions53 from high-income countries, are available.

The growing number of borrowers subject to surcharges and the expanding debt crisis suggest that this policy will remain an active barrier to sustainable recovery in developing countries for years to come. Historically, there are precedents for the elimination of the surcharge policy. Size-based surcharges were rescinded in 1974, and the graduated system of surcharges was altogether eliminated in 1981, after it failed to prevent larger and longer borrowing. Surcharges on arrears introduced during the debt crisis of the 1980s proved counterproductive and unnecessarily burdensome. When highly indebted countries in arrears failed to service these surcharges, the IMF suspended them in 1992 for all outstanding cases. It can do so again, permanently.

As the burden of IMF surcharges has grown and as their profound harms have come to light, there is widespread agreement that these surcharges should be eliminated. Calls to do so have come from leading economists;54 the UN Global Crisis Response Group on Food, Energy, and Finance;55 UN Secretary-General António Guterres;56 UN human rights experts;57 dozens of former heads of state and government;58 members of the US Congress,59 the G77,60 and the G24,61 which represent the interests of nearly every developing country; and numerous leaders of Global South countries, including Barbadian Prime Minister Mia Mottley62 and Brazilian president and G20 Chair Lula da Silva.63 Hundreds of civil society organizations worldwide, including Oxfam International, ActionAid International, Partners In Health, and the International Trade Union Confederation, have also urged the IMF to discontinue the surcharge policy.64

In response to this sustained pressure from international organizations, world leaders, and civil society groups, the IMF began to review the surcharge policy in the summer of 2024.65 The Fund should take this opportunity to end the harmful surcharge policy once and for all.

Arauz, Andrés and Ivana Vasic-Lalovic. 2024. “No More Excuses for Surcharges: the Target for Precautionary Balances Has Been Reached.” Washington, DC: Center for Economic and Policy Research, February. https://cepr.net/no-more-excuse-for-surcharges-the-target-for-precautionary-balances-has-been-reached/.

Arauz, Andrés and Odd Hansen. 2022. “IMF Projects No Losses if Surcharges Are Removed.” Washington, DC: Center for Economic and Policy Research, May. https://cepr.net/imf-projects-no-losses-if-surcharges-are-removed/.

Arauz, Andrés, Weisbrot, Mark, Laskaridis, Christina and Joe Sammut. 2021. “IMF Surcharges: Counterproductive and Unfair.” Washington, DC: Center for Economic and Policy Research, September. https://cepr.net/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/IMF-Surcharge-Final.pdf.

Bohoslavsky, J.P., F. Cantamutto, and L. Clérico. 2022. “IMF’s Surcharges as a Threat to the Right to Development.” Development 65: 194–202. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41301-022-00340-5.

Boughton, James M. 2001. Silent Revolution: The International Monetary Fund 1979-1989. International Monetary Fund. 811-812.

https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/history/2001/ch16.pdf.

Boughton, James M. 2012. Tearing Down Walls: The International Monetary Fund 1990-1999. International Monetary Fund. 801-814. https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/history/2012/pdf/c16.pdf.

Do Rosario, Jorgelina and Eric Martin. 2024. “IMF to Consider Options to Lower Penalties on Big Borrowers.” Bloomberg. July 8. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2024-07-08/imf-to-discuss-options-for-lowering-penalties-on-big-borrowers.

Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC). 2023. “Public debt and development distress in Latin America and the Caribbean.” United Nations. https://repositorio.cepal.org/server/api/core/bitstreams/d84a5041-0a2c-4b8e-9b01-d91b187477ce/content.

Galant, Michael and Alexander Main. 2024. “No False Solutions: IMF Surcharges Must Go.” Bretton Woods Observer. London: Bretton Woods Project, July. https://www.brettonwoodsproject.org/2024/07/no-false-solutions-imf-surcharges-must-go/.

Galant, Michael and Ivana Vasic-Lalovic. 2024. “International Monetary Fund Lifts Veil on Surcharges.” Washington, DC: Center for Economic and Policy Research, February. https://cepr.net/international-monetary-fund-lifts-veil-on-surcharges/.

Ghosh, Jayati. 2022. “Examining the Gendered and Other Impacts of IMF Surcharges.” Washington, DC: Center for Economic and Policy Research, May. https://cepr.net/examining-the-gendered-and-other-impacts-of-imf-surcharges-event-transcript/.

Group of 24 (G24). 2021. “The G24 Seeks the IMF to Eliminate Surcharges on Loans due to their ‘Regressive Nature’.” April 5. https://www.g24.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/The-G24-seeks-the-IMF-to-eliminate-surcharges-on-loans-due-to-their-_regressive-nature_-El-Economista.pdf.

Group of 77 and China (G77). 2023. “Havana Declaration on ‘Current Development Challenges: the Role of Science, Technology and Innovation.’” Havana, September 15-16. https://unsouthsouth.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/HAVANA-DECLARATION-2023.pdf.

Group of 77 and China (G77). 2024. “Statement on Behalf of the Group of 77 and China by H.E. Mr. Adonia Ayebare, Ambassador, Permanent Representative of Uganda to the United Nations, at the G-24 Ministers and Governors Spring Meeting 2024.” Washington, DC. April 16. https://www.g77.org/statement/getstatement.php?id=240416b.

International Monetary Fund (IMF). 1981. “Annual Report 1981.” https://www.elibrary.imf.org/display/book/9781616351939/9781616351939.xml.

____. 1997. “Annual Report of the Executive Board for the Financial Year Ended April 30, 1997.” 127-128. https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/AREB/Issues/2016/12/30/International-Monetary-Fund-Annual-Report-1997-2309

____. 1998. “Annual Report of the Executive Board for the Financial Year Ended April 30, 1998.” 143-144.

https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/AREB/Issues/2016/12/31/Annual-Report-of-the-Executive-Board-for-the-Financial-Year-Ended-April-30-1998.

____. 2000. “Review of Fund Facilities – Further Considerations: Supplementary Information on Rates of Charge.” July.

https://www.imf.org/external/np/pdr/roff/2000/eng/fcsi/index.htm.

____. 2016. “Review of Access Limits and Surcharge Policies.” Policy Papers, April. https://www.imf.org/external/np/pp/eng/2016/012016.pdf.

____. 2018. IMF Financial Operations 2018.

https://www.elibrary.imf.org/display/book/9781484330876/9781484330876.xml?result=1&rskey=2XSyRr.

____. 2020. “Articles of Agreement.” https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/aa/pdf/aa.pdf.

____. 2024. “Review of the Fund’s Income Position for FY 2024 and FY 2025-2026.” Policy Papers, May. https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/Policy-Papers/Issues/2024/05/10/Review-of-the-Funds-Income-Position-for-FY-2024-and-FY-2025-2026-548830.

Kofi Annan Foundation. 2022. “The Inaugural Kofi Annan Lecture delivered by Hon. Mia Amor Mottley.” September 23. https://www.kofiannanfoundation.org/news/kofi-annan-lecture-2022-mia-mottley/.

Laskaridis, Christina. 2022. “The Gendered Impacts of the IMF’s Harmful Surcharges Policy.” Washington, DC: Center for Economic and Policy Research, April. https://cepr.net/the-gendered-impacts-of-the-imfs-harmful-surcharges-policy/.

Manzanelli, Pablo. 2022. “Un Análisis sobre el Programa de Facilidades Extendidos Acordado con el FMI.” Buenos Aires: Centro de Investigación y Formación de la República Argentina, March. https://www.cta.org.ar/IMG/pdf/analisis_del_acuerdo_con_el_fmi.pdf.

Merling, Lara, Vasic-Lalovic, Ivana and Lorena Valle Cuellar. 2024. “The Rising Cost of Debt: An Obstacle to Achieving Climate and Development Goals.” Washington, DC: Center for Economic and Policy Research, April. https://cepr.net/report/the-rising-cost-of-debt-an-obstacle-to-achieving-climate-and-development-goals/.

Munevar, David. 2021. “A Guide to IMF Surcharges.” Brussels: European Network on Debt and Development, December.

https://www.eurodad.org/a_guide_to_imf_surcharges/#Global_costs_IMF_surcharges.

Sachs, Jeffrey D., and Steven Radelet. 1998. “The East Asian Financial Crisis: Diagnosis, Remedies, Prospects.” Brookings Papers on Economic Activity 1, The Brookings Institution: Washington, DC. https://www.brookings.edu/bpea-articles/the-east-asian-financial-crisis-diagnosis-remedies-prospects/.

United Nations (UN). 2022. “Caribbean ‘Ground Zero’ for Global Climate Emergency, Says Secretary-General, Addressing Government Heads at Regional Conference.” Press Release, SG/SM/21361. July 3. https://press.un.org/en/2022/sgsm21361.doc.htm.

United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD). 2024. “A World of Debt.” https://unctad.org/publication/world-of-debt.

United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). 2024. “No Soft Landing for Developing Economies.” https://www.undp.org/publications/no-soft-landing-developing-economies.

United Nations Global Crisis Response Group. 2022. “Global Impact of the War in Ukraine: Billions of People Face the Greatest Cost-of-Living Crisis in a Generation.” June. https://unctad.org/system/files/official-document/un-gcrg-ukraine-brief-no-2_en.pdf.

U.S. Congress. 2022. House. Amendment to Rules Committee Print 117-54 Offered by Mr. Garcia of Illinois. 117th Cong.

https://amendments-rules.house.gov/amendments/GARCIL_080_xml_final%20revised220708135856614.pdf.

____. 2022b. House. House Committee on Financial Services, Stop Onerous Surcharges Act. 117th Cong., H.R. 6979. https://www.congress.gov/bill/117th-congress/house-bill/6979/all-infos=3&r=1&q=%7B%22search%22%3A%22stop+onerous+surcharges+act%22%7D.

____. 2022c. Senate. Review of Loan Surcharge Policy of International Monetary Fund. S.Amdt. 6083 to S.Amdt. 5499. 117th Cong., H.R. 7900. https://www.congress.gov/amendment/117th-congress/senate-amendment/6083/text.

____. 2024. House. House Committee on Financial Services, Stop Onerous Surcharges Act. 118th Cong., H.R. 7902. https://www.congress.gov/bill/118th-congress/house-bill/7902?s=1&r=28.

Ramos-Horta, José, Türk, Danilo, Chinchilla Miranda, Laura and Han Seung-Soo. (2022) “Managing the Megacrisis of 2022.” Project Syndicate. July 19. https://www.project-syndicate.org/commentary/g20-must-take-on-food-energy-debt-crises-by-jose-ramos-horta-et-al-2022-07.

Vasic-Lalovic, Ivana, Galant, Michael and Francisco Amsler. 2024. “A Greater Burden Than Ever Before: An Updated Estimate of the IMF’s Surcharges.” Washington, DC: Center for Economic and Policy Research, April. https://cepr.net/report/a-broader-impact-than-ever-before-an-updated-estimate-of-the-imfs-surcharges/.

Waris, Attiya, Hopenhaym, Fernanda, Fry, Ian, Alfarargi, Saad, Fakhri, Michael, Sewanyana, Livingstone, Okafor, Obiora C., De Schutter, Olivier and Melissa Upreti. 2022. “Information on the differentiated impact of the surcharge policy that are part of the loan arrangements provided by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) on debt affected countries and the rights of their populations.” United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights. August 26. https://spcommreports.ohchr.org/TMResultsBase/DownLoadPublicCommunicationFile?gId=27523.

World Bank, Government of Ukraine, European Union and United Nations. 2024. “Ukraine: Third Rapid Damage and Needs Assessment.” February.

https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/099021324115085807/pdf/P1801741bea12c012189ca16d95d8c2556a.pdf.