June 10, 2015

The Atlantic recently published a piece on the universal basic income movement, whose advocates argue for an unconditional monthly allowance that is given to everyone to cover life’s basic necessities. Unfortunately, the piece is predicated on the assumption that increased automation and robots are taking the jobs of people now and will continue to do so, and that, as a basic income advocate stated, we are “seeing the effects all around us.”

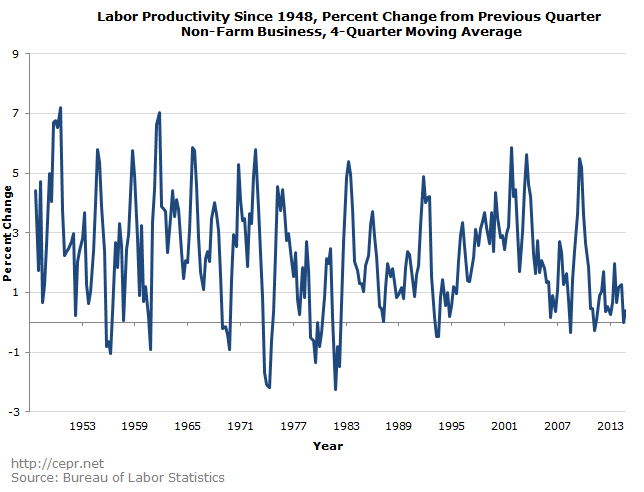

While it may be true that there is increasing automation, it has not created a large shift in the labor market and it is not the reason why the U.S. has wage inequality or slack in the labor market. Fortunately, there is an easy way to see if automation is having an effect on the labor market, and that’s by looking at how productive workers are. The graph below shows labor productivity growth as measured by the Bureau of Labor Statistics. If we believed the Atlantic’s narrative and the economy’s shift to automation were accelerating rapidly, we’d expect the growth in labor productivity to dramatically increase during the past few years. (An economy that has had a large shift toward automation would require fewer workers to produce the same output, so workers would be more productive.)

What we actually see is quite different. Labor productivity growth since 2010 has actually been quite low, and growth since the 1970s has been generally lower than in the 1950s and 1960s with the exception of a period peaking around 2001. From 1947 to the first quarter of 1973, for example, we saw average annual productivity growth of 3.0 percent. But over the past ten years, annual productivity growth has only averaged 1.3 percent.

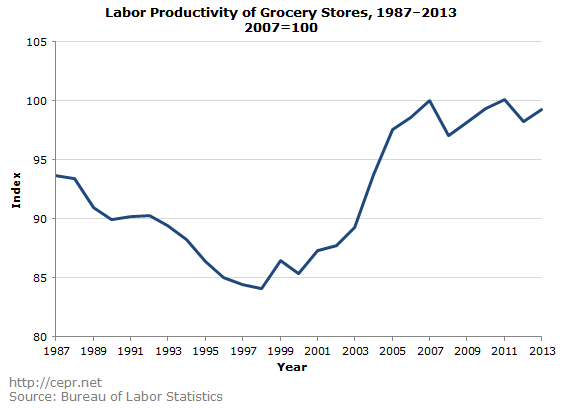

We can also look at indices of labor productivity for specific industries. Let’s take grocery stores as an example. Many grocers have installed automated checkouts in recent years. Let’s see if we can see that in the data.

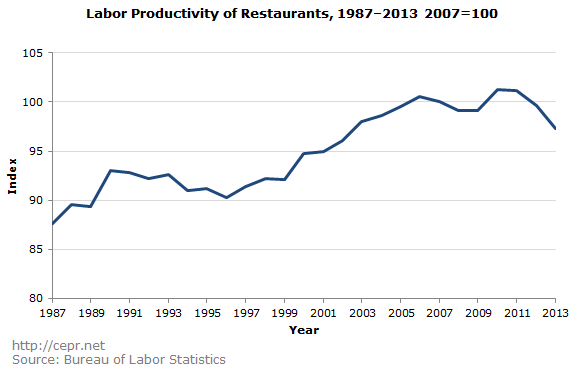

Since about 2005, labor productivity in grocery stores has stayed about the same, meaning near zero annual productivity growth. For restaurants, an industry that employs a large number of people, productivity has decreased recently.

These data suggest that, while productivity has seen modest increases in the last 20 years, there has not been a sudden increase that would indicate that automation could explain the social problems the Atlantic prescribes to it. Looking toward future trends, the article cites a popular study from Oxford University researchers that “warns 47 percent of all existing jobs are susceptible to automation within the next two decades.” But the study’s authors confess that they rely heavily on assumptions and “make no attempt to estimate how many jobs will actually be automated.” In general, it is notoriously difficult to make accurate predictions about technological change and how it will affect the future.

The article also spreads misconceptions about our current social safety net. It leaves an assertion that the U.S.’s current social safety net is a “bureaucratic nightmare” unchallenged as it promotes the simplicity of a basic income. This is very far from the truth. Social Security, as an example, is an extremely well-run program despite being constantly attacked by those who want it dismantled. The Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP, or commonly known as food stamps) is also efficient and effective, and as a means-tested program, can respond to economic recessions like it did in 2007–2009. It is sometimes advantageous for social programs to respond to changes in the economy and target certain demographics or needs, even if this makes the program’s administration more difficult. The basic income, as usually described, can’t do either of these things.

All of this is not to say that a government-managed universal basic income would not be good policy. But it’s important to realize that it also makes sense to push for a progressive agenda in general. This means forgetting about the robots, supporting complementary social programs like Social Security and SNAP, and pressing for good policy that can greatly help workers today, like preventing the Federal Reserve from raising interest rates.