December 29, 2014

Mark Weisbrot

Fortune, December 29, 2014

See article on original website

There have been numerous reports in the business press in the past couple of weeks that Venezuela will default on its bonds. A Bloomberg News reporter stated on December 9 that “it is not a question of if, but when” the government will default. Another Bloomberg article warned that Venezuela has $21 billion of debt due by the end of 2016 and only $21 billion in reserves – as if governments pay off their debt out of reserves. And CNN reports that “the spectre of default looms larger” for Venezuela, “which is deep in debt and has been burning through its foreign currency reserves.”

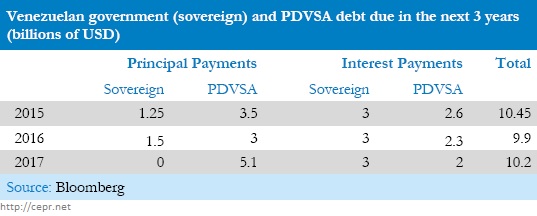

Should foreign investors believe these stories? When in doubt, it is usually a good idea to look at the numbers. There are two types of dollar-denominated bonds that these reports refer to: Venezuela’s sovereign or government bonds, and the bonds of the state oil company, PDVSA. Here are the totals for interest and principal due for the next three years:

The totals for each year are about $10 billion, of which roughly half is principal and half is interest. (After 2017, principal payments drop off to low levels.) Normally, Venezuela would be able to roll over the principal, i.e. issue new bonds for the principal coming due. That would leave approximately $5 billion in interest payments. Does anyone believe that a government with $50 billion in oil revenue (at the current price of $54 per barrel) can’t pay $5 billion in interest?

Apparently some people do. As of December 16, Venezuela’s sovereign bonds that mature in March were yielding a 76 percent rate annualized rate of return. PDVSA’s bonds maturing in 2017 were selling at 45 cents on the dollar. There are huge profits to be made for anyone who is willing to bet that Venezuela doesn’t default over the next three years and wins.

In fact, the prices of Venezuela’s bonds are so depressed right now that the government could buy up the whole stock of debt that comes due in the next three years, nominally worth about $14.3 billion, for less than $9 billion — and probably even less, since the government already owns some of that debt. And they have enough assets to sell – including $14 billion in gold – that they could do exactly this. If they are reluctant to sell the gold, they can swap it for cash. And then there is China, which has loaned Venezuela $46 billion over the last 8 years, with $24 billion having been paid back. Would China, which considers Venezuela to be a “strategic ally,” let the government default on its debt for lack of a few billion dollars or less?

Then there is Argentina, whose bonds offer another very high return, in part thanks to media coverage reporting that the country has already defaulted on its sovereign debt. This is somewhat misleading, since Argentina deposited the full interest payment on its sovereign bonds for distribution to creditors on June 30, only to have payment blocked by a New York Federal District judge. It is this “eccentric” judge, of questionable competence (to put it politely) who defaulted on these bonds, not the government of Argentina. But there are a number of ways to work around his decision and jurisdiction, and since the government is determined to pay its creditors, it will be done. The Argentine government’s foreign debt owed to private creditors is about 7 percent of its GDP; it would not make sense for any government to default on such a small amount of debt.

It is always a good idea to read the business press with a critical eye. In the case of countries where media bias is unusually strong, it can also be quite profitable for investors to do so.

Mark Weisbrot is co-director of the Center for Economic and Policy Research, in Washington, D.C. and president of Just Foreign Policy. He is also the author of the forthcoming book Failed: What the “Experts” Got Wrong About the Global Economy(Oxford University Press, 2015).