April 02, 2013

Just ahead of the midnight deadline set out by the U.S. 2nd Circuit Court of Appeals’ three-judge panel, Argentina’s government submitted a letter (view document here) describing how it would go about paying holders of defaulted bonds. The payments would be for creditors who refused to take part in two previous debt exchanges, including the so-called “vulture fund” plaintiffs in this ongoing case, NML Capital, Ltd. V. Republic of Argentina.

Following the letter’s submission, a number of financial analysts quoted in the major media were unimpressed by Argentina’s latest move. The Wall Street Journal noted that one portfolio manager said “There was some hope they would have a more rational approach to this exercise, but that’s definitely not the Argentina way.” Financial analyst Josh Rosner predicted to an AP reporter that “Monday morning is going to be a disaster.” He also asked, “What if somebody took that new bond, and the Argentine government defaulted the next day?” Rosner may have momentarily forgotten that the South American government has made timely payments on all the bonds issued in the 2005 and 2010 settlements. The gist of the response in the media was “more shenanigans from Argentina.”

But what was lost in most reactions in the media is that Argentina has made significant concessions to creditors that until recently it had vowed, on principle, not to offer. (The plaintiffs, for their part, have shown no willingness to compromise.) Furthermore, the terms offered to NML would represent a sizeable return on the fund’s original investments in 2008 and would satisfy the requirement under the pari passu clause—which is at the heart of the case— that all bondholders are treated equally. Indeed, to offer a sweeter deal would appear to violate that clause at the expense of bondholders who took part in the 2005 and 2010 exchanges and accepted restructured bonds worth between 25 and 29 cents on the dollar.

With this in mind, the offer that Argentina presented on Friday followed the terms of the 2010 exchange. Plaintiffs could choose between “Par” and “Discount” options. The former would be worth the face value of the original bonds and would pay interest rates rising from 2.5 percent to 5.25 percent until they came due in 2038. Plaintiffs would also receive an immediate payment of interest past due since 2003, the same period offered to participants in the 2010 exchange, and would receive “GDP units” that would pay them whenever Argentina’s GDP growth exceeds 3 percent per year. The “Par” option, meant for small-holders of Argentina bonds, is limited to $50,000 per series of bonds.

The second option offers discounted bonds, meant for the larger institutional investors, with interest rates of 8.25 percent, part of which would be added to the principal (and therefore accrues a greater total payout). Plaintiffs would also receive an upfront payment of past due interest, but at a higher (8.75 percent) rate than under the Par option, and GDP Units for when the economy grows beyond 3 percent.

As Argentina argues in its letter, the proposal “provides for a fair return going forward, and also gives an upside in the form of annual payments if Argentina’s economy grows.” This worked out for those who took part in previous exchanges, as the Argentine economy grew by 94 percent in real terms in the 10 years after default. Argentina goes on to make the argument that the plaintiffs cannot use the equal treatment clause—the case’s linchpin—to “compel payment on terms better than those received by the vast majority of creditors who experienced precisely the same default as plaintiffs, and whose restructured debt obligations arose out of, and served as consideration for the surrender of, the very same defaulted debt held by plaintiffs.”

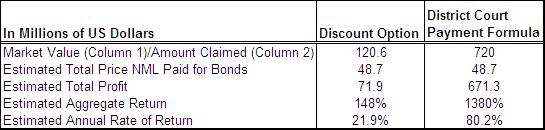

In its letter to the court, Argentina provides a breakdown of what it is offering to “vulture funds” versus what the payment formula from the original district court decision, of which the current proceedings are an appeal, would imply. The results can be seen in the following table.

The key point here is that the lead plaintiff, NML Capital, as well as the other “vulture funds,” bought most of this debt for just cents on the dollar after Argentina’s default. NML purchased the majority of their holdings from June-November 2008, paying an estimated $48.7 million for over $220 million in defaulted bonds, a price of just over 20 cents on the dollar. The Argentine offer, far from forcing NML to take a loss, would imply a 148 percent aggregate return in terms of current market value, and would become more valuable over time. This compares to the payment formula proposed by the district court, which would imply a 1,380 percent return for NML.

Despite what many reporters have written, Argentina—not the district court or NML Capital—appears to enjoy broad support in this case and on this particular legal matter. The list of institutions that have explicitly disagreed with the court’s ruling is formidable: the Bank of New York Mellon, the American Bankers Association, and the U.S. government, for starters. Given Washington’s recent relationship with Buenos Aires, it is striking to see the government so strenuously argue Argentina’s case, as it did in an amicus brief: “the district court’s interpretation of the pari passu provision could enable a single creditor to thwart the implementation of an internationally supported restructuring plan, and thereby undermine the decades of effort the United States has expended to encourage a system of cooperative resolution of sovereign debt crises.” It is even more striking given the expensive lobbying campaign on behalf of the “vulture funds.”

Argentina’s offer has fueled speculation among financial analysts that Argentina “is now much more likely” to default, as they do not expect the court to accept the offer. Yet unlike most cases of default, where a government either cannot or will not pay, a default for Argentina this time would be because the district court bars the government from making payments to bondholders who took part in previous exchanges. Argentine Vice President Amado Boudou stated over the weekend that “it would be a judicial absurdity to block payments by a country that has the capacity and willingness to pay.” He added, “one way or another, Argentina will pay.” If the court rules against Argentina and prevents the U.S.-based financial institution that makes payments on behalf of the government from paying bondholders, Argentina could use a different financial institution outside the jurisdiction of the New York courts to continue making payments.

What the case really boils down to, and what is often missing from discussions about NML or the court’s ruling, is that the court is siding with the vulture funds in a case in which they have no legitimate claim. The Argentine debt restructuring was not a choice—the government could not pay its debts after the economic collapse of 1998-2002. As a result, an agreement was reached between the creditors and the government. Of course, the debt in question is also arguably illegitimate—racked up by a military dictatorship working with international financiers, along with an economic collapse for which the international community, represented by the IMF, had a major responsibility. But even aside from these questions of legitimacy of the original debt, to give in to the vulture funds’ claim would be to deny the validity of any sovereign debt restructuring, for the enrichment of a few hedge fund managers. This is something that the world cannot afford, and it is indefensible. As the Jubilee USA Network, a coalition of civil society and faith-based organizations, said in a statement responding to Argentina’s recent letter, “the behavior of these vulture funds is morally bankrupt.”