As a Thanksgiving present to readers, Washington Post columnist Catherine Rampell decided to tell us again how old-timers are robbing from our children with their generous Social Security and Medicare benefits. This is always a popular theme at the WaPo, especially around the holiday season.

The story is infuriating for four reasons:

Social Security

The Social Security program has always been reasonably well-funded, even as slower growth and the upward redistribution of income over the last five decades have hurt the program’s finances. It is now projected to face a shortfall in a bit over a decade, but the gap between scheduled benefits and taxes is not exceptionally large, as calculated by Gene Steurele and Karen Smith, Rampell’s source.

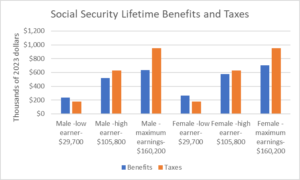

Source: Steurele and Smith, 2023.

The chart below above shows Steurele and Smith’s calculations for lifetime Social Security benefits and taxes, for people turning 65 in 2025, for men and women at different earnings levels. There are a few points worth noting on these calculations.

First, they are highly stylized, assuming that a worker puts in 43 years from age 22 to age 65 always earning the same wage relative to the overall average. This means that their wage rises year by year in step with inflation and the increase in average wages. No one actually would follow this pattern.

They are likely to earn less early in their career and more later in their career. They also are likely to have some years of little or no earnings. This is especially the case for women who are likely to spend some time outside of the paid labor force caring for children or parents. These adjustments would generally lead to higher benefits relative to taxes.

The second point is that the calculations assume that everyone lives to age 65 at which point they start to collect benefits. Some people will die before they can collect benefits, so we are looking at the benefits for workers who survive to collect benefits. (Social Security also has survivors’ benefits that go to spouses and minor children of deceased workers, so their tax payments are not necessarily a complete loss.)

The third point is that Steurele and Smith have opted to use a 2.0 percent real (inflation-adjusted) interest rate to discount taxes and benefits. This is a standard rate to use in this sort of analysis, but one could argue for a higher or lower rate. A higher rate would make the program seem less generous, while a lower rate would raise benefits relative to taxes.

As can be seen, low earners are projected to receive more in benefits than they pay in taxes. An important qualification here is that there is a large and growing gap in life expectancies between low and higher earners. These calculations assume that everyone of the same gender has the same life expectancy regardless of their income. This means that the benefits will be somewhat overstated for low earners and understated for high earners.

Ignoring the life expectancy issue, the chart shows that projected benefits end up being less than taxes once we get to high earners ($105,800 in 2023). For men projected lifetime taxes exceed benefits by $106,000. For women the gap is smaller at $49,000, reflecting their longer life expectancy.

Moving to maximum earners, people who earn the income at which the payroll tax is capped ($160,200 in 2023), the gaps become larger. In the case of men, projected lifetime taxes exceed benefits by $319,000. For women, projected lifetime taxes are $249,000 more than benefits.

There are some simple takeaways we can get from the Steurele and Smith analysis. First, for low and middle-wage earners Social Security does indeed pay out more in benefits than workers pay in taxes. However, the gap is not very large. For average earners, who got $66,100 in 2023, (not shown to keep the size of the graph manageable), the gap is $3,000 for men and $46,000 for women.

For higher income earners taxes actually exceed benefits. In the case of maximum earners, these excess payments are actually fairly large, as noted $319,000 for men and $249,000 for women.

This raises an interesting issue, if we are looking to cut benefits to reduce the “subsidy” to the elderly provided by Social Security. We can cut back benefits by a substantial percentage for low earners to bring their lifetime benefits more closely in line with their lifetime taxes, but do we really want to reduce retirement benefits for people who had average earnings of $29,700?

We can make some cuts for more middle-income workers, but someone earning $66,100 during their working lifetime was not terribly comfortable, and there is not much subsidy here to start, especially with men. When we get to higher earners, taxes already exceed benefits. We can still make cuts to their benefits, but we would not be taking back a subsidy by this calculation, we would be increasing their net overpayment to the program.

It’s also worth noting who is a high earner in this story. The high earner had annual earnings of $105,800 in 2023. President Biden promised that he would not raise taxes on couples earning less than $400,000. That puts his cutoff of $200,000 at almost twice the high earner level, and the calculation of lifetime benefits and taxes turns negative at a considerably lower income than the stylized high earner.

These calculations show that if we just take Social Security in isolation and want to reduce the subsidy implied here we either have to cut benefits for people who are not living comfortably by most standards, or we have to cut benefits for people who are not currently receiving a subsidy. We may decide that the latter is good policy, but we should be clear that it is not taking back a subsidy.

There is an important qualification to this discussion. Married couples will generally do better in these calculations than single workers. This is because the spousal benefit allows the spouse to collect the greater of their own benefit or half of their spouse’s benefit. Also, a surviving spouse will receive the greater of their own or their deceased spouse’s benefit. For these reasons, lifetime benefits for couples will generally be higher relative to taxes than for single individuals.

The Medicare Subsidy and the Broken Healthcare System Story

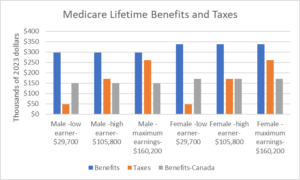

The Steurele and Smith analysis shows much larger subsidies for the Medicare program, as shown below.

There are a few qualifications to these calculations that should be noted. First, the same caveats about earnings patterns that were noted with the Social Security calculations also apply to the projected value of Medicare taxes.

Second, the differences in life expectancies by income matter here also when assessing the size of the tax penalty or subsidy. The program is less generous for low earners than shown in this figure and more generous for high earners.

The third point is that, unlike with the designated Social Security tax, the Medicare tax is not capped. This means that people earning above the Social Security cap will be paying more taxes to support the program. For very high earners ($185,000 for men and $207,000 for women), projected taxes would exceed benefits. The size of the tax penalty increases further up the income scale.

Finally, high-income people also pay a designated Medicare tax on capital income, like dividends and capital gains. For these people, it is virtually guaranteed that their Medicare taxes exceed their projected benefits.

With these caveats, we see the same general story as with Social Security, where there is more of a subsidy for lower earners than higher earners. While the overall gaps are larger for Medicare, projected benefits exceed taxes by a larger amount, this changes less with income than in the case of Social Security.

This is due to the fact that, unlike Social Security, the payout is not designed to be progressive, with all retirees getting in principle the same benefit.[1] This is qualified by the fact that higher-income retirees can expect to receive benefits for a considerably longer period of time, making the benefit regressive.

I have added a third bar to this graph, labeled “Benefits-Canada.” This is a calculation of what the cost of benefits would be if we paid the same amount per person for our healthcare as Canada does. The Medicare program appears as a huge subsidy to beneficiaries primarily because we pay so much more for our health care than people in other wealthy countries.

According to the OECD, we pay 57 percent more per person than Germany, 107 percent more than France, and 99 percent more than Canada. This sort of massive gap can be shown with U.S. costs relative to every other wealthy country. We don’t get any obvious benefit in terms of better healthcare outcomes from this additional spending. Life expectancy in the United States is considerably shorter than in most other wealthy countries.

The “Benefits-Canada” bar allows us to assess the value of Medicare benefits if our healthcare costs were more in line with those in other countries. It multiplies the projected value of Medicare benefits by the ratio of per person health care costs in Canada to costs in the United States (50.3 percent).

As can be seen, if we calculate Medicare benefits assuming that we pay as much for our health care as people in Canada, most of the calculated subsidy goes away. Low earners still receive a substantial subsidy, $102,000 for men and $122,000 for women, but this quickly goes away higher up the income ladder.

If we assume Canadian health care costs, a high-earning male has a net Medicare tax penalty of $21,000, while a high-earning woman has a net tax penalty of just under $1,000. For those earning at the Social Security maximum, the net tax penalty for men is $111,000, and for women it’s $91,000.

The implication of this calculation is that the seemingly large subsidies that Medicare provides to retirees is not due to the generosity of benefits, it is due to the fact that we overpay for our healthcare. Medicare is not providing a large subsidy to retirees, it is providing a large subsidy for drug companies, medical equipment suppliers, insurers, and doctors. (In case you are wondering, people in the U.S. are not generally paid much more than people in other wealthy countries. Our manufacturing workers get considerably lower pay.)

We pay roughly twice as much in all of these categories as people in other wealthy countries. It is misleading to imply that these overpayments are generous to retirees. While all of these interest groups have powerful lobbies, which makes it politically difficult to bring their compensation in line with other wealthy countries, we should at least be honest about who is getting subsidized by the high cost of our Medicare program.

What Do Subsidies Mean, When the Government Structures the Market?

There is another aspect of these calculations that should have jumped out at people when I noted that the designated Medicare tax is not capped and also applies to capital income. The taxes that are designated for these programs are arbitrary. We can designate other taxes that people pay as being Social Security and Medicare taxes, and apparent subsidies will disappear.

In fact, the idea that we can make a clear distinction between income that people have somehow earned, and income that is given to them by the government, is in fact an illusion. The government structures the markets in ways that allow some people to get very wealthy and keep others on the edge of subsistence.

Those who make big bucks in the healthcare industry are just one example. While our trade policy was quite explicitly designed to open the door to cheap manufactured goods, we actually have increased the barriers that make it difficult for foreign-trained doctors to practice in the United States.

We have made patent and copyright monopolies longer and stronger. The government subsidizes bio-medical research and then gives private companies monopoly control over the product. In a recent example, we paid Moderna to develop a COVID vaccine and then gave them control over it, creating at least five Moderna billionaires.

We have allowed our financial sector to become incredibly bloated, creating many millionaires and billionaires, even as we demand efficiency elsewhere. We give Elon Musk and Mark Zuckerberg Section 230 protection against defamation suits that their counterparts in print and broadcast media do not enjoy.

And, as was recently highlighted with the UAW strike, our CEOs make far more than the CEOS of comparably sized companies in other wealthy countries. The difference is as much as a factor of ten in the case of Japanese companies. This is not due to the natural workings of the market, this is the result of a corrupt corporate governance structure that allows the CEOs to have their friends set their pay.

Yes, I am again talking about my book (it’s free). It is absurd to obsess about tax and transfer policy while ignoring the ways in which the government structures the market to determine winners and losers. It is understandable that the right would like tax and transfer policy to be the focus of public debate, since the default is a market outcome that leaves most money with the rich.

However, it is beyond absurd that people who consider themselves progressive would accept this framing. We can structure the market differently to get more equitable market outcomes. This should be front and center in public debate. Unfortunately, the right wants to hide the fact that we can structure the market differently, and progressives are all too willing to go along.

Future of the Planet

There is a final point on the sort of generational scorecard implied by these calculations of Social Security and Medicare benefits. We don’t just hand our children a tax bill, we hand them an entire economy, society, and planet.

If we experience anything resembling normal economic growth, average wages will be far higher twenty or thirty years from now than they are today. Will the typical worker see these wage gains? That will depend on distribution within generations, not between generations.

We also see costs from items like the military. When I was growing up in the 1960s we paid a much larger share of our GDP to support the Cold War. (Young men were also drafted.) We will again pay lots more money for the military if we have a new Cold War with China. The implied taxes don’t figure into the Social Security and Medicare calculations, but will be every bit as much of a drain on the income of people in the future as taxes for these programs.

And, we should always have global warming front and center. If we paid off the national debt and eliminated the programs to support retirees, but did nothing to restrain global warming, our children and grandchildren would not have much reason to thank us. First and foremost, we must give them a livable planet.

Phony Answers to a Phony Question

The whole subsidy to retiree story is a diversion from the many important issues facing the country. Even the core idea, that we don’t adequately support the young because we give too much to the elderly is wrong.

We saw this very clearly in the debate over the extension of the child tax credit. As with everything in Congress, much is determined by narrow political considerations. Republicans had no interest in giving President Biden and the Democrats a win, but the bill could have passed without Republican votes.

The deciding factor was the refusal of West Virginia Senator Joe Manchin to support the bill. Senator Manchin was very clear on his concerns. He didn’t argue that we were spending too much on retirees, he didn’t want low-income people to have the money.

This is in general the story as to why we don’t have adequate funding for early childhood education, children’s nutrition, day care and other programs that would benefit children. There is a substantial political bloc that does not want to fund these programs. And, they still would not want to fund these programs even if we didn’t pay a dime for Social Security and Medicare.

[1] This is not strictly true, since the premium payment that retirees make for Part B and Part D of the Medicare program depends on income in retirement.

As a Thanksgiving present to readers, Washington Post columnist Catherine Rampell decided to tell us again how old-timers are robbing from our children with their generous Social Security and Medicare benefits. This is always a popular theme at the WaPo, especially around the holiday season.

The story is infuriating for four reasons:

Social Security

The Social Security program has always been reasonably well-funded, even as slower growth and the upward redistribution of income over the last five decades have hurt the program’s finances. It is now projected to face a shortfall in a bit over a decade, but the gap between scheduled benefits and taxes is not exceptionally large, as calculated by Gene Steurele and Karen Smith, Rampell’s source.

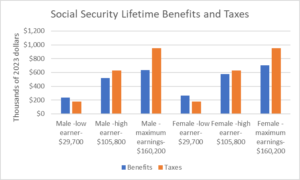

Source: Steurele and Smith, 2023.

The chart below above shows Steurele and Smith’s calculations for lifetime Social Security benefits and taxes, for people turning 65 in 2025, for men and women at different earnings levels. There are a few points worth noting on these calculations.

First, they are highly stylized, assuming that a worker puts in 43 years from age 22 to age 65 always earning the same wage relative to the overall average. This means that their wage rises year by year in step with inflation and the increase in average wages. No one actually would follow this pattern.

They are likely to earn less early in their career and more later in their career. They also are likely to have some years of little or no earnings. This is especially the case for women who are likely to spend some time outside of the paid labor force caring for children or parents. These adjustments would generally lead to higher benefits relative to taxes.

The second point is that the calculations assume that everyone lives to age 65 at which point they start to collect benefits. Some people will die before they can collect benefits, so we are looking at the benefits for workers who survive to collect benefits. (Social Security also has survivors’ benefits that go to spouses and minor children of deceased workers, so their tax payments are not necessarily a complete loss.)

The third point is that Steurele and Smith have opted to use a 2.0 percent real (inflation-adjusted) interest rate to discount taxes and benefits. This is a standard rate to use in this sort of analysis, but one could argue for a higher or lower rate. A higher rate would make the program seem less generous, while a lower rate would raise benefits relative to taxes.

As can be seen, low earners are projected to receive more in benefits than they pay in taxes. An important qualification here is that there is a large and growing gap in life expectancies between low and higher earners. These calculations assume that everyone of the same gender has the same life expectancy regardless of their income. This means that the benefits will be somewhat overstated for low earners and understated for high earners.

Ignoring the life expectancy issue, the chart shows that projected benefits end up being less than taxes once we get to high earners ($105,800 in 2023). For men projected lifetime taxes exceed benefits by $106,000. For women the gap is smaller at $49,000, reflecting their longer life expectancy.

Moving to maximum earners, people who earn the income at which the payroll tax is capped ($160,200 in 2023), the gaps become larger. In the case of men, projected lifetime taxes exceed benefits by $319,000. For women, projected lifetime taxes are $249,000 more than benefits.

There are some simple takeaways we can get from the Steurele and Smith analysis. First, for low and middle-wage earners Social Security does indeed pay out more in benefits than workers pay in taxes. However, the gap is not very large. For average earners, who got $66,100 in 2023, (not shown to keep the size of the graph manageable), the gap is $3,000 for men and $46,000 for women.

For higher income earners taxes actually exceed benefits. In the case of maximum earners, these excess payments are actually fairly large, as noted $319,000 for men and $249,000 for women.

This raises an interesting issue, if we are looking to cut benefits to reduce the “subsidy” to the elderly provided by Social Security. We can cut back benefits by a substantial percentage for low earners to bring their lifetime benefits more closely in line with their lifetime taxes, but do we really want to reduce retirement benefits for people who had average earnings of $29,700?

We can make some cuts for more middle-income workers, but someone earning $66,100 during their working lifetime was not terribly comfortable, and there is not much subsidy here to start, especially with men. When we get to higher earners, taxes already exceed benefits. We can still make cuts to their benefits, but we would not be taking back a subsidy by this calculation, we would be increasing their net overpayment to the program.

It’s also worth noting who is a high earner in this story. The high earner had annual earnings of $105,800 in 2023. President Biden promised that he would not raise taxes on couples earning less than $400,000. That puts his cutoff of $200,000 at almost twice the high earner level, and the calculation of lifetime benefits and taxes turns negative at a considerably lower income than the stylized high earner.

These calculations show that if we just take Social Security in isolation and want to reduce the subsidy implied here we either have to cut benefits for people who are not living comfortably by most standards, or we have to cut benefits for people who are not currently receiving a subsidy. We may decide that the latter is good policy, but we should be clear that it is not taking back a subsidy.

There is an important qualification to this discussion. Married couples will generally do better in these calculations than single workers. This is because the spousal benefit allows the spouse to collect the greater of their own benefit or half of their spouse’s benefit. Also, a surviving spouse will receive the greater of their own or their deceased spouse’s benefit. For these reasons, lifetime benefits for couples will generally be higher relative to taxes than for single individuals.

The Medicare Subsidy and the Broken Healthcare System Story

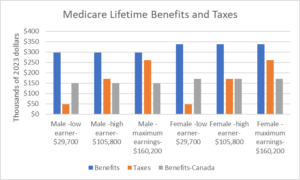

The Steurele and Smith analysis shows much larger subsidies for the Medicare program, as shown below.

There are a few qualifications to these calculations that should be noted. First, the same caveats about earnings patterns that were noted with the Social Security calculations also apply to the projected value of Medicare taxes.

Second, the differences in life expectancies by income matter here also when assessing the size of the tax penalty or subsidy. The program is less generous for low earners than shown in this figure and more generous for high earners.

The third point is that, unlike with the designated Social Security tax, the Medicare tax is not capped. This means that people earning above the Social Security cap will be paying more taxes to support the program. For very high earners ($185,000 for men and $207,000 for women), projected taxes would exceed benefits. The size of the tax penalty increases further up the income scale.

Finally, high-income people also pay a designated Medicare tax on capital income, like dividends and capital gains. For these people, it is virtually guaranteed that their Medicare taxes exceed their projected benefits.

With these caveats, we see the same general story as with Social Security, where there is more of a subsidy for lower earners than higher earners. While the overall gaps are larger for Medicare, projected benefits exceed taxes by a larger amount, this changes less with income than in the case of Social Security.

This is due to the fact that, unlike Social Security, the payout is not designed to be progressive, with all retirees getting in principle the same benefit.[1] This is qualified by the fact that higher-income retirees can expect to receive benefits for a considerably longer period of time, making the benefit regressive.

I have added a third bar to this graph, labeled “Benefits-Canada.” This is a calculation of what the cost of benefits would be if we paid the same amount per person for our healthcare as Canada does. The Medicare program appears as a huge subsidy to beneficiaries primarily because we pay so much more for our health care than people in other wealthy countries.

According to the OECD, we pay 57 percent more per person than Germany, 107 percent more than France, and 99 percent more than Canada. This sort of massive gap can be shown with U.S. costs relative to every other wealthy country. We don’t get any obvious benefit in terms of better healthcare outcomes from this additional spending. Life expectancy in the United States is considerably shorter than in most other wealthy countries.

The “Benefits-Canada” bar allows us to assess the value of Medicare benefits if our healthcare costs were more in line with those in other countries. It multiplies the projected value of Medicare benefits by the ratio of per person health care costs in Canada to costs in the United States (50.3 percent).

As can be seen, if we calculate Medicare benefits assuming that we pay as much for our health care as people in Canada, most of the calculated subsidy goes away. Low earners still receive a substantial subsidy, $102,000 for men and $122,000 for women, but this quickly goes away higher up the income ladder.

If we assume Canadian health care costs, a high-earning male has a net Medicare tax penalty of $21,000, while a high-earning woman has a net tax penalty of just under $1,000. For those earning at the Social Security maximum, the net tax penalty for men is $111,000, and for women it’s $91,000.

The implication of this calculation is that the seemingly large subsidies that Medicare provides to retirees is not due to the generosity of benefits, it is due to the fact that we overpay for our healthcare. Medicare is not providing a large subsidy to retirees, it is providing a large subsidy for drug companies, medical equipment suppliers, insurers, and doctors. (In case you are wondering, people in the U.S. are not generally paid much more than people in other wealthy countries. Our manufacturing workers get considerably lower pay.)

We pay roughly twice as much in all of these categories as people in other wealthy countries. It is misleading to imply that these overpayments are generous to retirees. While all of these interest groups have powerful lobbies, which makes it politically difficult to bring their compensation in line with other wealthy countries, we should at least be honest about who is getting subsidized by the high cost of our Medicare program.

What Do Subsidies Mean, When the Government Structures the Market?

There is another aspect of these calculations that should have jumped out at people when I noted that the designated Medicare tax is not capped and also applies to capital income. The taxes that are designated for these programs are arbitrary. We can designate other taxes that people pay as being Social Security and Medicare taxes, and apparent subsidies will disappear.

In fact, the idea that we can make a clear distinction between income that people have somehow earned, and income that is given to them by the government, is in fact an illusion. The government structures the markets in ways that allow some people to get very wealthy and keep others on the edge of subsistence.

Those who make big bucks in the healthcare industry are just one example. While our trade policy was quite explicitly designed to open the door to cheap manufactured goods, we actually have increased the barriers that make it difficult for foreign-trained doctors to practice in the United States.

We have made patent and copyright monopolies longer and stronger. The government subsidizes bio-medical research and then gives private companies monopoly control over the product. In a recent example, we paid Moderna to develop a COVID vaccine and then gave them control over it, creating at least five Moderna billionaires.

We have allowed our financial sector to become incredibly bloated, creating many millionaires and billionaires, even as we demand efficiency elsewhere. We give Elon Musk and Mark Zuckerberg Section 230 protection against defamation suits that their counterparts in print and broadcast media do not enjoy.

And, as was recently highlighted with the UAW strike, our CEOs make far more than the CEOS of comparably sized companies in other wealthy countries. The difference is as much as a factor of ten in the case of Japanese companies. This is not due to the natural workings of the market, this is the result of a corrupt corporate governance structure that allows the CEOs to have their friends set their pay.

Yes, I am again talking about my book (it’s free). It is absurd to obsess about tax and transfer policy while ignoring the ways in which the government structures the market to determine winners and losers. It is understandable that the right would like tax and transfer policy to be the focus of public debate, since the default is a market outcome that leaves most money with the rich.

However, it is beyond absurd that people who consider themselves progressive would accept this framing. We can structure the market differently to get more equitable market outcomes. This should be front and center in public debate. Unfortunately, the right wants to hide the fact that we can structure the market differently, and progressives are all too willing to go along.

Future of the Planet

There is a final point on the sort of generational scorecard implied by these calculations of Social Security and Medicare benefits. We don’t just hand our children a tax bill, we hand them an entire economy, society, and planet.

If we experience anything resembling normal economic growth, average wages will be far higher twenty or thirty years from now than they are today. Will the typical worker see these wage gains? That will depend on distribution within generations, not between generations.

We also see costs from items like the military. When I was growing up in the 1960s we paid a much larger share of our GDP to support the Cold War. (Young men were also drafted.) We will again pay lots more money for the military if we have a new Cold War with China. The implied taxes don’t figure into the Social Security and Medicare calculations, but will be every bit as much of a drain on the income of people in the future as taxes for these programs.

And, we should always have global warming front and center. If we paid off the national debt and eliminated the programs to support retirees, but did nothing to restrain global warming, our children and grandchildren would not have much reason to thank us. First and foremost, we must give them a livable planet.

Phony Answers to a Phony Question

The whole subsidy to retiree story is a diversion from the many important issues facing the country. Even the core idea, that we don’t adequately support the young because we give too much to the elderly is wrong.

We saw this very clearly in the debate over the extension of the child tax credit. As with everything in Congress, much is determined by narrow political considerations. Republicans had no interest in giving President Biden and the Democrats a win, but the bill could have passed without Republican votes.

The deciding factor was the refusal of West Virginia Senator Joe Manchin to support the bill. Senator Manchin was very clear on his concerns. He didn’t argue that we were spending too much on retirees, he didn’t want low-income people to have the money.

This is in general the story as to why we don’t have adequate funding for early childhood education, children’s nutrition, day care and other programs that would benefit children. There is a substantial political bloc that does not want to fund these programs. And, they still would not want to fund these programs even if we didn’t pay a dime for Social Security and Medicare.

[1] This is not strictly true, since the premium payment that retirees make for Part B and Part D of the Medicare program depends on income in retirement.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Eduardo Porter had an interesting column in the Washington Post last week in which he argued that trade will be important in slowing climate change. The basic point is that we could do a lot to reduce emissions by encouraging people to buy items where they are produced with the least emissions. The point is well-taken even if Porter’s preferred mechanism, a carbon tax, is a political impossibility for the foreseeable future.

However, what is striking in Porter’s piece, and others making similar arguments, is the refusal to talk about trade in intellectual products, which is arguably a far more important issue in addressing climate change. If that claim sounds strange, it’s probably because of the taboo on even raising the issue in polite discussions.

The basic point is that the United States and other countries are developing a wide range of technologies in areas like wind and solar energy, electric cars, and energy storage, which will be essential for reducing greenhouse gas emissions. If we want these technologies to be as widely adopted as quickly as possible, we should want them to be freely available to everyone at the point they are developed.

In fact, our laws on intellectual property are explicitly designed to prevent technology from being freely available. Patent monopolies prevent anyone from using technologies without the permission of the patent holder.

These monopolies are an extreme form of protection. While modern tariffs rarely exceed 25 or 30 percent, a patent monopoly can make the price of a protected item two or three times its free market price, the equivalent of a tariff of 200 or 300 percent. If we want people to quickly switch to wind or solar power we should want wind turbines and solar panels selling at prices as close to their production cost as possible, not patent monopoly protected prices.

There is the obvious point that we need to provide people with an incentive to innovate in these areas, and the patent monopoly does that. This is true, but there are other ways to provide incentives, most notably we can just pay them upfront for the research.

This is what we did with Moderna when it contracted with Operation Warp Speed to develop a Covid vaccine. The government paid Moderna almost a billion dollars to develop and test the vaccine. Since it was paid upfront, the risk was entirely on the government’s hands. If it turned out that it didn’t work, the government would have been out a billion and Moderna would have still made a decent profit on its work.

Thankfully, the vaccine did work so the government’s money was well spent. Incredibly, we also gave Moderna control over the vaccine, enabling it to make tens of billions of dollars on government-funded research and creating at least five Moderna billionaires.

We can take the first half of the Moderna model and apply it to climate change technologies. We can pay money for the research and then let the resulting innovations sell in a free market. Ideally, we would arrange for other countries to also fund research, making its output freely available as well.

Going this route would also have the advantage that we could require that all funded research be fully open, with results posted on the web as quickly as practical. This would allow researchers everywhere to benefit quickly from the latest findings of other researchers anywhere in the world. They could then build on successes and avoid dead ends.

Unfortunately, the Washington Post and other leading media outlets won’t even allow this sort of discussion of free trade. Needless to say, patent monopolies contribute enormously to inequality in the distribution of income, and those who own and control major media outlets would rather not have questions about patent protection and other forms of intellectual property raised in polite company.

That was the story with the pandemic. The obvious route to have taken at the start of the pandemic, if saving lives was the issue, was to have complete sharing of technology among all countries. We could sort out later who should be compensated and how much.

At the end of the day, some companies or individuals may walk away thinking they didn’t get what they deserved, but so what? We could have spread vaccines, tests, and treatments far more quickly, likely saving millions of lives.

Anyhow, the moral of this story is that as much as trade will be important to dealing with climate change, in polite circles we can only talk about some types of trade. If we start raising questions about the protections that provide the basis for the income of many of the rich, then discussions of trade are not on the agenda.

Eduardo Porter had an interesting column in the Washington Post last week in which he argued that trade will be important in slowing climate change. The basic point is that we could do a lot to reduce emissions by encouraging people to buy items where they are produced with the least emissions. The point is well-taken even if Porter’s preferred mechanism, a carbon tax, is a political impossibility for the foreseeable future.

However, what is striking in Porter’s piece, and others making similar arguments, is the refusal to talk about trade in intellectual products, which is arguably a far more important issue in addressing climate change. If that claim sounds strange, it’s probably because of the taboo on even raising the issue in polite discussions.

The basic point is that the United States and other countries are developing a wide range of technologies in areas like wind and solar energy, electric cars, and energy storage, which will be essential for reducing greenhouse gas emissions. If we want these technologies to be as widely adopted as quickly as possible, we should want them to be freely available to everyone at the point they are developed.

In fact, our laws on intellectual property are explicitly designed to prevent technology from being freely available. Patent monopolies prevent anyone from using technologies without the permission of the patent holder.

These monopolies are an extreme form of protection. While modern tariffs rarely exceed 25 or 30 percent, a patent monopoly can make the price of a protected item two or three times its free market price, the equivalent of a tariff of 200 or 300 percent. If we want people to quickly switch to wind or solar power we should want wind turbines and solar panels selling at prices as close to their production cost as possible, not patent monopoly protected prices.

There is the obvious point that we need to provide people with an incentive to innovate in these areas, and the patent monopoly does that. This is true, but there are other ways to provide incentives, most notably we can just pay them upfront for the research.

This is what we did with Moderna when it contracted with Operation Warp Speed to develop a Covid vaccine. The government paid Moderna almost a billion dollars to develop and test the vaccine. Since it was paid upfront, the risk was entirely on the government’s hands. If it turned out that it didn’t work, the government would have been out a billion and Moderna would have still made a decent profit on its work.

Thankfully, the vaccine did work so the government’s money was well spent. Incredibly, we also gave Moderna control over the vaccine, enabling it to make tens of billions of dollars on government-funded research and creating at least five Moderna billionaires.

We can take the first half of the Moderna model and apply it to climate change technologies. We can pay money for the research and then let the resulting innovations sell in a free market. Ideally, we would arrange for other countries to also fund research, making its output freely available as well.

Going this route would also have the advantage that we could require that all funded research be fully open, with results posted on the web as quickly as practical. This would allow researchers everywhere to benefit quickly from the latest findings of other researchers anywhere in the world. They could then build on successes and avoid dead ends.

Unfortunately, the Washington Post and other leading media outlets won’t even allow this sort of discussion of free trade. Needless to say, patent monopolies contribute enormously to inequality in the distribution of income, and those who own and control major media outlets would rather not have questions about patent protection and other forms of intellectual property raised in polite company.

That was the story with the pandemic. The obvious route to have taken at the start of the pandemic, if saving lives was the issue, was to have complete sharing of technology among all countries. We could sort out later who should be compensated and how much.

At the end of the day, some companies or individuals may walk away thinking they didn’t get what they deserved, but so what? We could have spread vaccines, tests, and treatments far more quickly, likely saving millions of lives.

Anyhow, the moral of this story is that as much as trade will be important to dealing with climate change, in polite circles we can only talk about some types of trade. If we start raising questions about the protections that provide the basis for the income of many of the rich, then discussions of trade are not on the agenda.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The Washington Post ran another “trash the Biden economy, let the facts be damned” piece today. The theme is that the economy is really awful for new college grads. The paper finds us a few real-life examples of struggling recent grads to make its case.

The problem is that the data in the article actually tell the opposite story. While it tells us that the unemployment rate for recent college grads is higher than for the workforce as a whole, it actually is lower than it had been for most of the decade prior to the pandemic.

In fact, instead of being a bad time for recent college grads, the data shown in the graph in the article indicate that their employment prospects are relatively good today. Their unemployment rate was more than 30 percent higher a decade ago.

In fact, this is a point made by the economists featured in the article. The experience of recent grads only looks bad compared to the strong labor market for other workers, it is not a story of recent grads becoming impoverished.

This fact comes out in the other major data point in the piece, the share of young adults (ages 18 to 24) living at home. While it tells us that the share is higher than in 2019, the chart in the piece tells a different story.

For men in this age group, the share living at home is higher than lows hit in 2005-07, just before the Great Recession, but well below the average of the last two decades. There had been an upward trend in the share of women in this age group living at home, with a big pandemic jump. This pandemic jump has now been largely reversed. In other words, the story here is that fewer young women are living at home.

So, the Post really doesn’t have a case for new college grads struggling, but it apparently wants to tell a bad economy story and doesn’t intend to let reality stand in the way.

The Washington Post ran another “trash the Biden economy, let the facts be damned” piece today. The theme is that the economy is really awful for new college grads. The paper finds us a few real-life examples of struggling recent grads to make its case.

The problem is that the data in the article actually tell the opposite story. While it tells us that the unemployment rate for recent college grads is higher than for the workforce as a whole, it actually is lower than it had been for most of the decade prior to the pandemic.

In fact, instead of being a bad time for recent college grads, the data shown in the graph in the article indicate that their employment prospects are relatively good today. Their unemployment rate was more than 30 percent higher a decade ago.

In fact, this is a point made by the economists featured in the article. The experience of recent grads only looks bad compared to the strong labor market for other workers, it is not a story of recent grads becoming impoverished.

This fact comes out in the other major data point in the piece, the share of young adults (ages 18 to 24) living at home. While it tells us that the share is higher than in 2019, the chart in the piece tells a different story.

For men in this age group, the share living at home is higher than lows hit in 2005-07, just before the Great Recession, but well below the average of the last two decades. There had been an upward trend in the share of women in this age group living at home, with a big pandemic jump. This pandemic jump has now been largely reversed. In other words, the story here is that fewer young women are living at home.

So, the Post really doesn’t have a case for new college grads struggling, but it apparently wants to tell a bad economy story and doesn’t intend to let reality stand in the way.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Can you imagine doing a 1300-word piece on how ordinary people are faring in the economy and never once mentioning unemployment? Apparently, the New York Times opinion page editors don’t think jobs matter to people, since they ran a column by Karen Petrou (the managing partner of Federal Financial Analytics) that didn’t mention unemployment once. The piece is titled “Why Voters Aren’t Buying Biden’s Boasts About Bidenomics” and uses a cornucopia of bad economics to argue the case against Biden.

It’s hard to know where to begin in addressing this piece, so it’s probably best to start where the piece starts.

“On Oct. 26, the Department of Commerce announced that gross domestic product had grown at an annual rate of 4.9 percent in the third quarter. This growth rate ran well above even optimistic forecasts, leading to what can only be called triumphalism from a White House dead-set on making “Bidenomics” a key to its 2024 presidential campaign. President Biden issued a self-congratulatory statement, the White House echoed it over and over — and Donald Trump’s relative popularity increased.”

Like every president, Biden has talked about economic growth. But he also talks about jobs and wages, sort of like all the time, as when he touted the big wage gains by UAW workers following their strike (which he supported). In fact, the very next week after the GDP report, Biden was very happy to boast about the 21st consecutive month of unemployment below 4.0 percent when the October jobs data were released.

Low unemployment is actually a very big deal for workers, not only because it means they have jobs, but it means that they can leave jobs they don’t like and find better ones. Workers have been doing this in large numbers since the unemployment rate fell to extraordinarily low levels in early 2022. As a result, according to the Conference Board, workplace satisfaction is at its highest level in the nearly forty years they have conducted the survey.

Biden also was happy to boast about wages that were outstripping inflation, a point that sort of squeaks through in the confusion in Petrou’s piece. The piece includes a graph of nominal wage growth and nominal price growth.

The graph shows wage growth modestly outstripping prices through most of Trump’s term, and then hugely outstripping prices in 2020. For Biden we get the opposite story, prices outpaced wages in 2021, then hugely outpaced wages in 2022, but inflation then dropped and wages are again outpacing inflation, with the biggest gains for those at the bottom (contrary to what Petrou told readers).

The pattern here is not much of a mystery to people who follow the economy. Wages hugely outstripped prices in 2020 because tens of millions of low-paid workers in restaurants, hotels and other service industries lost their jobs. When you get rid of low-paid workers, the average wage rises, just as the average height in a room increases if we get the short people to leave.

We saw the opposite story in 2021 as low-paid workers got their jobs back. We also did have the problem of serious supply disruptions created by the pandemic and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. As the supply problems have eased inflation has come back down.

Inflation due to the pandemic was a worldwide phenomenon, not just something that hit the United States. In fact, we have dealt with the problem very well. The U.S. inflation rate is now the second lowest among major economies, only slightly higher than Japan’s.

It is fair to say that people don’t care that things are worse in Germany or Canada, they care about their own finances. But, Petrou is quite explicitly making an attack on Bidenomics as policy, not the fact that the economy has faced huge headwinds that would have caused serious problems regardless of what policies were pursued.

Ignoring the importance of the pandemic and the Russian invasion would be like complaining about the shortage of housing in an area just devastated by a hurricane and not noting the hurricane. It is understandable that the average person might recognize the damage done by a hurricane more readily than the economic damage caused by the pandemic, but it would be reasonable to expect that a person writing for the New York Times would be familiar with the impact of the pandemic.

Petrou highlights polls showing that most people think that the economy is doing badly and they are not buying Biden’s boasts. That is true, but a recent poll gives us important insights on this point.

The poll shows that roughly half the people think that the economy in their town or city is doing okay, but just 26 percent think the national economy is doing well. This huge gap between people’s assessment of their local economy and their assessment of the national economy cannot be explained by their personal experience. Rather this gap must be attributable to things that they are hearing about the economy from places like Fox News and the New York Times.

Can you imagine doing a 1300-word piece on how ordinary people are faring in the economy and never once mentioning unemployment? Apparently, the New York Times opinion page editors don’t think jobs matter to people, since they ran a column by Karen Petrou (the managing partner of Federal Financial Analytics) that didn’t mention unemployment once. The piece is titled “Why Voters Aren’t Buying Biden’s Boasts About Bidenomics” and uses a cornucopia of bad economics to argue the case against Biden.

It’s hard to know where to begin in addressing this piece, so it’s probably best to start where the piece starts.

“On Oct. 26, the Department of Commerce announced that gross domestic product had grown at an annual rate of 4.9 percent in the third quarter. This growth rate ran well above even optimistic forecasts, leading to what can only be called triumphalism from a White House dead-set on making “Bidenomics” a key to its 2024 presidential campaign. President Biden issued a self-congratulatory statement, the White House echoed it over and over — and Donald Trump’s relative popularity increased.”

Like every president, Biden has talked about economic growth. But he also talks about jobs and wages, sort of like all the time, as when he touted the big wage gains by UAW workers following their strike (which he supported). In fact, the very next week after the GDP report, Biden was very happy to boast about the 21st consecutive month of unemployment below 4.0 percent when the October jobs data were released.

Low unemployment is actually a very big deal for workers, not only because it means they have jobs, but it means that they can leave jobs they don’t like and find better ones. Workers have been doing this in large numbers since the unemployment rate fell to extraordinarily low levels in early 2022. As a result, according to the Conference Board, workplace satisfaction is at its highest level in the nearly forty years they have conducted the survey.

Biden also was happy to boast about wages that were outstripping inflation, a point that sort of squeaks through in the confusion in Petrou’s piece. The piece includes a graph of nominal wage growth and nominal price growth.

The graph shows wage growth modestly outstripping prices through most of Trump’s term, and then hugely outstripping prices in 2020. For Biden we get the opposite story, prices outpaced wages in 2021, then hugely outpaced wages in 2022, but inflation then dropped and wages are again outpacing inflation, with the biggest gains for those at the bottom (contrary to what Petrou told readers).

The pattern here is not much of a mystery to people who follow the economy. Wages hugely outstripped prices in 2020 because tens of millions of low-paid workers in restaurants, hotels and other service industries lost their jobs. When you get rid of low-paid workers, the average wage rises, just as the average height in a room increases if we get the short people to leave.

We saw the opposite story in 2021 as low-paid workers got their jobs back. We also did have the problem of serious supply disruptions created by the pandemic and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. As the supply problems have eased inflation has come back down.

Inflation due to the pandemic was a worldwide phenomenon, not just something that hit the United States. In fact, we have dealt with the problem very well. The U.S. inflation rate is now the second lowest among major economies, only slightly higher than Japan’s.

It is fair to say that people don’t care that things are worse in Germany or Canada, they care about their own finances. But, Petrou is quite explicitly making an attack on Bidenomics as policy, not the fact that the economy has faced huge headwinds that would have caused serious problems regardless of what policies were pursued.

Ignoring the importance of the pandemic and the Russian invasion would be like complaining about the shortage of housing in an area just devastated by a hurricane and not noting the hurricane. It is understandable that the average person might recognize the damage done by a hurricane more readily than the economic damage caused by the pandemic, but it would be reasonable to expect that a person writing for the New York Times would be familiar with the impact of the pandemic.

Petrou highlights polls showing that most people think that the economy is doing badly and they are not buying Biden’s boasts. That is true, but a recent poll gives us important insights on this point.

The poll shows that roughly half the people think that the economy in their town or city is doing okay, but just 26 percent think the national economy is doing well. This huge gap between people’s assessment of their local economy and their assessment of the national economy cannot be explained by their personal experience. Rather this gap must be attributable to things that they are hearing about the economy from places like Fox News and the New York Times.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Local journalism serves an essential public service, providing people with information about the problems facing their communities and efforts to address them. It is also an essential check on corruption. Journalists have exposed a vast number of crimes in both the public and private sector.

Without effective journalism, it is a sure bet there would be far more corruption than is currently the case. We may not know about it, because no one would be reporting on it, but we would be paying for it in higher prices, lower quality and less safe products, and less safe working conditions and lower pay.

As it stands, local journalism is not profitable without government support. The problem is that the information reporters uncover can be transferred at essentially zero cost. This was always the case, but it became especially true in the Internet Age, where information can be passed along instantly over the web. (Government-granted copyright monopolies are one form of public subsidy, but this has diminished value when information can be quickly circulated over the web.)

While the public might benefit hugely from knowing that a politician is stealing their tax dollars, the market does not require them to pay the reporters who discover the theft. If no one pays the reporters who do the investigating, then we don’t get the investigations, and the theft continues unchecked.

Addressing the Funding Shortfall

There are at least two ongoing efforts to support local journalism through a system of individual vouchers. One of them is still in nascent form in Seattle and the other is a bill introduced in Washington, DC by City Councilmember Janeese Lewis George. These proposals stem from work that has been done over recent decades on ways to support journalism as newspapers close and the survivors lay off journalists.

The proposals are still works in progress, but the basic idea is that a sum of money would be put aside for individuals to allocate to support the journalistic work of their choice. In the DC proposal, which is now available on the web, the work that is supported through this mechanism would be freely available to the public without paywalls. There are differences in how the mechanism works and what journalism qualifies for funding, but the basic principle is straightforward.

The logic of an individual voucher system is that it lets individuals decide which news outlets are worth their support. Rather than having the government determine which news outlets and journalists should be supported, this leaves the choice to individuals.

The closest analogy to this sort of system is the tax deduction for charitable contributions. Under this system, to qualify for tax-deductible contributions, an organization has to register with the I.R.S. and state what it does that qualifies for tax-exempt status. The I.R.S. simply verifies that the organization does what it claims. It makes no effort to determine whether the organization is a good museum, think tank, or church. It only determines that it is a museum, think tank, or church. It is up to the individuals donating the money to determine which ones merit their contributions.

The government would play a comparable role with local journalism vouchers. It would set rules as to what qualifies as local journalism and would ensure that news outlets meet these criteria. It is up to individuals to determine which outlets merit their vouchers.

Criticism of the Local Journalism Voucher Model

While this approach is just now gaining some public traction, there have already been some serious criticisms raised. Specifically, Brier Dudley, the Seattle Times Free Press editor, has raised a number of objections to the proposal being crafted in Seattle.

He has a serious perspective on this issue, and his points are worth addressing. He argues that vouchers have serious problems. He suggests as an alternative, the Journalism Competition and Preservation Act, a bill that has been introduced in Congress, which would allow smaller news outlets to collectively negotiate with Google, Meta, and other Internet platforms for a portion of their ad revenue.

The first and most important point in Dudley’s criticism is the potential problem of low participation. Dudley points out that participation rates for Seattle’s democracy voucher program is very low. This program is to some extent a model for the news voucher program. Under the democracy voucher program, voters in Seattle get public money in the form of vouchers that they can contribute to support the campaigns of candidates for local office. This program has been very expensive to administer and only around 10 percent of the vouchers have been used.

Dudley also points out that there have been some questionable uses of these vouchers, with one candidate apparently spending more money in winning democracy vouchers than in winning votes. This is a very serious concern.

There is a way around this problem, which the DC bill uses. The amount of the voucher is not fixed in advance, rather the total funding is fixed and the amount of the voucher adjusts to the number that are used. The entire system is on-line so this minimizes any costs associated with distributing and collecting physical vouchers.

This means, for example, if $10 million is designated for the program (a bit less than the $11 million actual sum in DC) and 100,000 people use the voucher, then each one is worth $100. If only 10,000 people decide to use the voucher, then each one is worth $1,000.

This approach has two important effects. First, it ensures that a substantial sum will be distributed to support local journalism from the program’s inception. Low participation will not translate into an underfunded program. This also means that news outlets will understand that there is money available to them, if they choose to seek it out.

The second is that the problem of low participation is likely to be self-correcting. If only 10,000 people participate, and each voucher ends up being worth $1,000, it is likely to get people angry. Their route to correct the problem is to use the vouchers themselves.

This parallels a story that Alan Greenspan tells in his autobiography. As Chair of the Federal Reserve Board, Greenspan sat on the board of the Resolution Trust Corporation (RTC), the agency set up to sell off the assets of the Savings and Loans that went bankrupt in the 1980s.

In the RTC’s first major auction, assets sold at ridiculously low prices. There were stories of perfectly fine middle-class homes selling for $5,000, which was absurdly low even then. These stories created a mini-scandal. However, they led to many more people taking part in later auctions, which led to much more reasonable prices.

According to Greenspan in his autobiography, the low prices and mini-scandal was by design. He knew that reports of great bargains would increase interest in the auctions. (I don’t believe him, I think they just failed to publicize the auctions adequately.)

Anyhow, there is a valid point here that the DC design of the news voucher system takes into account. If people see that they will have a large chunk of money to give to whatever news outlets they value, they will take advantage of the opportunity to use the money. If the first round has low participation, it is likely that the high value of each voucher will lead many more people to participate in subsequent rounds.

Dudley is of course right that any sort of subsidy system does pose a risk of abuse. The most immediate check is that people ideally have some knowledge of the news outlet to whom they are contributing, and won’t give their money to an outlet that doesn’t perform useful work. But there are no guarantees.

We know that there are many cases where charities abuse their I.R.S. tax-exempt status, which effectively is a taxpayer subsidy of 40 cents on each dollar given. There are instances where the top people running charities line their pockets and actually use very little of their donations for the ostensible purpose of the organization. In spite of these abuses, there are relatively few voices calling for the elimination of the deduction for charitable contributions. (It is worth noting that Mr. Dudley’s employer, the Seattle Times, has opted to take advantage of this subsidy by setting up a non-profit to support investigative journalism.)

The Journalism Competition and Preservation Act as an Alternative

The main thrust of the Journalism Competition and Preservation Act (JCPA) is to effectively provide an anti-trust exception, so that smaller news outlets can collectively negotiate with the Internet giants. While this would likely be good policy (the Internet giants do have huge market power), it is not likely to be sufficient to reverse the loss of funding to local news outlets in recent decades.

Extrapolating from the experience in Australia, where negotiations have yielded roughly $50 million in annual revenue, a comparable law in the U.S. would yield in the neighborhood of $600 to $800 million annually. That would clearly be a substantial help, but would not nearly make up for the drop in revenue to newspapers over the last three decades.

There are also two areas where the voucher approach has a huge advantage over the JCPA. First, the voucher approach would not just look to preserve the current structure in the news business. It is consciously intended to open the door to new voices and perspectives. This is a huge issue, since public trust in the media has fallen through the floor in recent decades.

It is understandable that the prospect of new competition might make some of the existing news outlets unhappy, but if we want news media that are truly responsive to the public’s needs, we should be trying to structure it in a way that opens as many doors as possible. The voucher system does this, whereas the JCPA simply gets more funding for existing outlets.

The other important advantage of the voucher system is that it will produce material that is available to the public at no cost. We want people to have as much access to information as possible. While it might be good for people to buy subscriptions to their local paper, most people don’t. Even if there are ways around paywalls and people can still share information, ideally we should want information to be spread as cheaply as possible.

Economists usually want items to sell at their marginal cost. This means the price should be what it cost to produce one more loaf of bread, one more shirt, or one more paper clip. The marginal cost of transferring a news article is zero. The voucher system allows for it to sell at that price, the current system does not. This makes it as cheap as possible to have a well-informed public since anyone with access to the web could have full access to all the material supported by the voucher system.

Local or National Measures

Dudley also argues that the problem of supporting local journalism is far better addressed at the national level, since it is a national problem. Also, the national government’s finances are far more robust than those of any city. Even in a downturn, the federal government is not restricted in its spending.

This point is well-taken, but it ignores the current political environment. We have one house of Congress controlled by a party that seems to think shutting down the government is an end in itself. Even the JCPA is likely an undoable lift with a Republican Party that seems unwilling to do anything that might impinge on corporate profits.

A major part of the rationale for creating voucher systems at the local level is to show that they are workable. If Seattle and Washington, DC take the lead in setting up these systems, and they prove popular, other cities are sure to follow. And, if there is a track record of success, it is likely there will be a push to have a public journalism voucher system implemented nationally.

There are many examples of policies advancing along these lines, notably unemployment insurance and the minimum wage. Congress is quite reasonably reluctant to take big steps in uncharted water, but when a system has been demonstrated to be effective at the state or local level, there is less risk in adopting it nationally. Congress also then has the benefit of seeing the plusses and minuses of a system that is actually in practice, rather than drawing it up from scratch.

In short, adopting a system like the journalism vouchers at the local level is not an alternative to doing it at the national level. It is a necessary step in that direction.

Local Journalism Vouchers – Big Potential Gains, Little Downside Risk

The proposals being crafted in Seattle and Washington, DC draw on several decades of analysis and debate among academics and journalists. They surely are not perfect, but they offer a clear route for addressing a real problem.

Even if they are adopted and there ends up being less to show than their advocates (including me) expect, we will not walk away empty-handed. Some number of news outlets and serious reporters will be supported with this funding. There will be investigations that would not have otherwise been undertaken and news stories that would not have been written and read. Perhaps most importantly, the system will have supported a number of journalists for its duration, helping them to develop skills, which they can then use in other contexts, even if the voucher system does not survive.

For these reasons, there seems very little downside risk in trying the local journalism voucher route. And, there are enormous potential benefits.

Local journalism serves an essential public service, providing people with information about the problems facing their communities and efforts to address them. It is also an essential check on corruption. Journalists have exposed a vast number of crimes in both the public and private sector.

Without effective journalism, it is a sure bet there would be far more corruption than is currently the case. We may not know about it, because no one would be reporting on it, but we would be paying for it in higher prices, lower quality and less safe products, and less safe working conditions and lower pay.

As it stands, local journalism is not profitable without government support. The problem is that the information reporters uncover can be transferred at essentially zero cost. This was always the case, but it became especially true in the Internet Age, where information can be passed along instantly over the web. (Government-granted copyright monopolies are one form of public subsidy, but this has diminished value when information can be quickly circulated over the web.)

While the public might benefit hugely from knowing that a politician is stealing their tax dollars, the market does not require them to pay the reporters who discover the theft. If no one pays the reporters who do the investigating, then we don’t get the investigations, and the theft continues unchecked.

Addressing the Funding Shortfall

There are at least two ongoing efforts to support local journalism through a system of individual vouchers. One of them is still in nascent form in Seattle and the other is a bill introduced in Washington, DC by City Councilmember Janeese Lewis George. These proposals stem from work that has been done over recent decades on ways to support journalism as newspapers close and the survivors lay off journalists.

The proposals are still works in progress, but the basic idea is that a sum of money would be put aside for individuals to allocate to support the journalistic work of their choice. In the DC proposal, which is now available on the web, the work that is supported through this mechanism would be freely available to the public without paywalls. There are differences in how the mechanism works and what journalism qualifies for funding, but the basic principle is straightforward.

The logic of an individual voucher system is that it lets individuals decide which news outlets are worth their support. Rather than having the government determine which news outlets and journalists should be supported, this leaves the choice to individuals.

The closest analogy to this sort of system is the tax deduction for charitable contributions. Under this system, to qualify for tax-deductible contributions, an organization has to register with the I.R.S. and state what it does that qualifies for tax-exempt status. The I.R.S. simply verifies that the organization does what it claims. It makes no effort to determine whether the organization is a good museum, think tank, or church. It only determines that it is a museum, think tank, or church. It is up to the individuals donating the money to determine which ones merit their contributions.

The government would play a comparable role with local journalism vouchers. It would set rules as to what qualifies as local journalism and would ensure that news outlets meet these criteria. It is up to individuals to determine which outlets merit their vouchers.

Criticism of the Local Journalism Voucher Model

While this approach is just now gaining some public traction, there have already been some serious criticisms raised. Specifically, Brier Dudley, the Seattle Times Free Press editor, has raised a number of objections to the proposal being crafted in Seattle.

He has a serious perspective on this issue, and his points are worth addressing. He argues that vouchers have serious problems. He suggests as an alternative, the Journalism Competition and Preservation Act, a bill that has been introduced in Congress, which would allow smaller news outlets to collectively negotiate with Google, Meta, and other Internet platforms for a portion of their ad revenue.

The first and most important point in Dudley’s criticism is the potential problem of low participation. Dudley points out that participation rates for Seattle’s democracy voucher program is very low. This program is to some extent a model for the news voucher program. Under the democracy voucher program, voters in Seattle get public money in the form of vouchers that they can contribute to support the campaigns of candidates for local office. This program has been very expensive to administer and only around 10 percent of the vouchers have been used.

Dudley also points out that there have been some questionable uses of these vouchers, with one candidate apparently spending more money in winning democracy vouchers than in winning votes. This is a very serious concern.

There is a way around this problem, which the DC bill uses. The amount of the voucher is not fixed in advance, rather the total funding is fixed and the amount of the voucher adjusts to the number that are used. The entire system is on-line so this minimizes any costs associated with distributing and collecting physical vouchers.

This means, for example, if $10 million is designated for the program (a bit less than the $11 million actual sum in DC) and 100,000 people use the voucher, then each one is worth $100. If only 10,000 people decide to use the voucher, then each one is worth $1,000.

This approach has two important effects. First, it ensures that a substantial sum will be distributed to support local journalism from the program’s inception. Low participation will not translate into an underfunded program. This also means that news outlets will understand that there is money available to them, if they choose to seek it out.

The second is that the problem of low participation is likely to be self-correcting. If only 10,000 people participate, and each voucher ends up being worth $1,000, it is likely to get people angry. Their route to correct the problem is to use the vouchers themselves.

This parallels a story that Alan Greenspan tells in his autobiography. As Chair of the Federal Reserve Board, Greenspan sat on the board of the Resolution Trust Corporation (RTC), the agency set up to sell off the assets of the Savings and Loans that went bankrupt in the 1980s.

In the RTC’s first major auction, assets sold at ridiculously low prices. There were stories of perfectly fine middle-class homes selling for $5,000, which was absurdly low even then. These stories created a mini-scandal. However, they led to many more people taking part in later auctions, which led to much more reasonable prices.

According to Greenspan in his autobiography, the low prices and mini-scandal was by design. He knew that reports of great bargains would increase interest in the auctions. (I don’t believe him, I think they just failed to publicize the auctions adequately.)

Anyhow, there is a valid point here that the DC design of the news voucher system takes into account. If people see that they will have a large chunk of money to give to whatever news outlets they value, they will take advantage of the opportunity to use the money. If the first round has low participation, it is likely that the high value of each voucher will lead many more people to participate in subsequent rounds.

Dudley is of course right that any sort of subsidy system does pose a risk of abuse. The most immediate check is that people ideally have some knowledge of the news outlet to whom they are contributing, and won’t give their money to an outlet that doesn’t perform useful work. But there are no guarantees.

We know that there are many cases where charities abuse their I.R.S. tax-exempt status, which effectively is a taxpayer subsidy of 40 cents on each dollar given. There are instances where the top people running charities line their pockets and actually use very little of their donations for the ostensible purpose of the organization. In spite of these abuses, there are relatively few voices calling for the elimination of the deduction for charitable contributions. (It is worth noting that Mr. Dudley’s employer, the Seattle Times, has opted to take advantage of this subsidy by setting up a non-profit to support investigative journalism.)

The Journalism Competition and Preservation Act as an Alternative

The main thrust of the Journalism Competition and Preservation Act (JCPA) is to effectively provide an anti-trust exception, so that smaller news outlets can collectively negotiate with the Internet giants. While this would likely be good policy (the Internet giants do have huge market power), it is not likely to be sufficient to reverse the loss of funding to local news outlets in recent decades.

Extrapolating from the experience in Australia, where negotiations have yielded roughly $50 million in annual revenue, a comparable law in the U.S. would yield in the neighborhood of $600 to $800 million annually. That would clearly be a substantial help, but would not nearly make up for the drop in revenue to newspapers over the last three decades.