In keeping with its apparent commitment to ignore the data and insist homeownership is no longer possible, the New York Times ran yet another piece on how homeownership is becoming impossible for young people. The piece begins with the sad story of a young woman worried whether she and her spouse will ever be able to own a home.

“Cameron Ambrosy spent the first weekend of December going to 10 open houses — purely for research purposes. The 25-year-old in St. Paul, Minn., has a well-paying job and she and her husband are saving diligently, but she knows that it will be years before they can afford to buy.

“‘It is much more of a long-term goal than for my parents or my grandparents, or even my peers who are slightly older,’ said Ms. Ambrosy, adding that for many of her friends, homeownership is even farther away. ‘There’s a lot of nihilism around long-term goals like home buying.’”

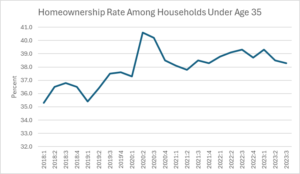

It is unfortunate to hear about this nihilism. It would have been helpful to note that it does not correspond to the data. While homeownership rates have fallen back somewhat in the last few quarters, as a result of the sharp jump in mortgage rates, they are still above the pre-pandemic levels.

This is true across the board, including for young people. The graph below shows the homeownership rate for households under age 35.

Source: Census Bureau, Table 6.

Note that in the most recent quarter, the homeownership rate for households under 35 was 38.3 percent, which is up from 37.6 percent in the fourth quarter of 2019, the last quarter before the pandemic.[1] That was when Donald Trump was still in the White House and the New York Times was not running article after article about how young people could not afford to buy houses.

Let me just repeat this point for the benefit of any elite types that might be reading this. The New York Times has repeatedly run pieces on the impossibility of homeownership for young people during the Biden administration. It did not run pieces on the impossibility of homeownership among young people when the homeownership rate was lower during the Trump administration.

Now, there is clearly an issue at the moment with high mortgage rates, but mortgage rates always fluctuate, and even the article notes that they have already fallen and are likely to fall further in the near future. It would be a bit bizarre for someone to have little hope of owning a home for long into the future based on a short-term rise in mortgage rates that is already being reversed.

If mortgage rates follow the 10-year Treasury bond rate downward, and the extraordinarily large gap between the 30-year mortgage rate and the 10-year Treasury bond rate is reduced, we may be looking at mortgage rates below 6.0 percent before long. That’s still somewhat higher than the pre-pandemic rate, but not high by historic standards.

The piece also talks about the runup in rents. This is undoubtedly a big deal for young people, since they are twice as likely to be renters as the rest of the population. However, it would be worth pointing out that rental inflation has pretty much stopped and rents may actually be falling.

Indexes of apartments that come on the market are now showing that rents have leveled off over the last half year. This slowdown in rental inflation will eventually show up in the government data, however, there is a lag, since the government rental indexes include all rental units, not just the ones that turn over. However, people actively looking for an apartment would be benefitting now from the lower inflation, or even falling rents.

It may well be the case that young people see a huge crisis in the housing market, but in that case the story should be how their perceptions are so much at odds with the reality, not an article that wrongly implies the reality is horrible.

[1] The big jump in ownership rates in 2020 was likely an artifact of the shutdown, when response rates to the survey plunged. (Correction: It has been pointed out to me that the 2020 rise was due to young people moving back in with their families during the pandemic. This reduced the number of households, raising the share who were homeowners.)

In keeping with its apparent commitment to ignore the data and insist homeownership is no longer possible, the New York Times ran yet another piece on how homeownership is becoming impossible for young people. The piece begins with the sad story of a young woman worried whether she and her spouse will ever be able to own a home.

“Cameron Ambrosy spent the first weekend of December going to 10 open houses — purely for research purposes. The 25-year-old in St. Paul, Minn., has a well-paying job and she and her husband are saving diligently, but she knows that it will be years before they can afford to buy.

“‘It is much more of a long-term goal than for my parents or my grandparents, or even my peers who are slightly older,’ said Ms. Ambrosy, adding that for many of her friends, homeownership is even farther away. ‘There’s a lot of nihilism around long-term goals like home buying.’”

It is unfortunate to hear about this nihilism. It would have been helpful to note that it does not correspond to the data. While homeownership rates have fallen back somewhat in the last few quarters, as a result of the sharp jump in mortgage rates, they are still above the pre-pandemic levels.

This is true across the board, including for young people. The graph below shows the homeownership rate for households under age 35.

Source: Census Bureau, Table 6.

Note that in the most recent quarter, the homeownership rate for households under 35 was 38.3 percent, which is up from 37.6 percent in the fourth quarter of 2019, the last quarter before the pandemic.[1] That was when Donald Trump was still in the White House and the New York Times was not running article after article about how young people could not afford to buy houses.

Let me just repeat this point for the benefit of any elite types that might be reading this. The New York Times has repeatedly run pieces on the impossibility of homeownership for young people during the Biden administration. It did not run pieces on the impossibility of homeownership among young people when the homeownership rate was lower during the Trump administration.

Now, there is clearly an issue at the moment with high mortgage rates, but mortgage rates always fluctuate, and even the article notes that they have already fallen and are likely to fall further in the near future. It would be a bit bizarre for someone to have little hope of owning a home for long into the future based on a short-term rise in mortgage rates that is already being reversed.

If mortgage rates follow the 10-year Treasury bond rate downward, and the extraordinarily large gap between the 30-year mortgage rate and the 10-year Treasury bond rate is reduced, we may be looking at mortgage rates below 6.0 percent before long. That’s still somewhat higher than the pre-pandemic rate, but not high by historic standards.

The piece also talks about the runup in rents. This is undoubtedly a big deal for young people, since they are twice as likely to be renters as the rest of the population. However, it would be worth pointing out that rental inflation has pretty much stopped and rents may actually be falling.

Indexes of apartments that come on the market are now showing that rents have leveled off over the last half year. This slowdown in rental inflation will eventually show up in the government data, however, there is a lag, since the government rental indexes include all rental units, not just the ones that turn over. However, people actively looking for an apartment would be benefitting now from the lower inflation, or even falling rents.

It may well be the case that young people see a huge crisis in the housing market, but in that case the story should be how their perceptions are so much at odds with the reality, not an article that wrongly implies the reality is horrible.

[1] The big jump in ownership rates in 2020 was likely an artifact of the shutdown, when response rates to the survey plunged. (Correction: It has been pointed out to me that the 2020 rise was due to young people moving back in with their families during the pandemic. This reduced the number of households, raising the share who were homeowners.)

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

There is a clear disconnect between how people rate the economy (the general economy, not their own economic condition – which most say is good) and standard measures of economic performance. This disconnect has led to a “vibes” vs economic reality debate, with one side arguing that negative news coverage and social media have led people to rate the economy poorly, while the other side argues that weak or declining real incomes explain negative attitudes.

Nate Cohn entered the vibes vs real economic conditions controversy with a unique contribution. He said that even though most standard economic measures, like employment, wages, and income suggest that people are doing pretty well, “factors dragging down consumers aren’t neatly captured by the usual economic statistics.”

“…some basic things have become harder. It’s harder to hire. It’s harder to get a loan. It’s more expensive to buy things. At times it was impossible to buy things because of supply chain shortages. It’s harder to buy a home. It’s harder to sell a home. If you wanted to engage in these kinds of economic activities, you should have done them before the fall of 2021.”

Cohn’s comments here are obviously speculative, he presents no data to support these assertions, but it’s worth considering the idea more carefully.

Some things definitely are harder today than in prior years, like buying and selling a home. With mortgage rates peaking at over 8.0 percent (they are now back under 7.0 percent), sales of existing homes fell by close to one-third from the 2021 pace. This is bad news, but still, the people who are actively looking to buy or sell a home in a given year (around 6 million, typically) are a relatively small share of the population.

Also, if we are looking at the negative story of high-interest rates, we should also look at the positive story that 14 million homeowners refinanced a mortgage during the period of low-interest rates from 2020-2022. Those who refinanced without taking out additional cash saved an average of more than $2,600 a year on interest payments. These savings do not show up in our standard data on income or disposable income.

Cohn tells us that it is harder to hire. This is true, but how many of us are looking to hire people? I suppose if we are looking for people to do work around the house, this could be the case. That is “the hard to get good help” theory of economic malaise.

The obvious flip side of it being harder to hire is that it is easier to find work. Ease of finding work is also not picked up in standard economic statistics and, as a practical matter, there are far more people who would be looking to find work than to hire.

We then have the claim that things are more expensive. That is true, but incomes have grown by more, and this is picked up in our economic statistics.

But then we have the claim that it is harder to buy things. There were certainly shortages of many items in 2021 and even into 2022, making it harder to buy many items. But by 2023, most of these shortages have disappeared. If this were a major factor in people’s economic discontent, we should have seen consumer sentiment improving over the course of the year, instead of deteriorating.

There also is another side to this issue. Online sales have exploded since the pandemic. Online sales accounted for 12.6 percent of retail sales in 2019. They now account for 16.7 percent of retail sales, an increase of more than a third. And this only counts the sales by online distributors, it does not include the growth of Internet sales for brick-and-mortar retailers or the explosion in food delivery from restaurants.

There are other important ways in which life has gotten easier that don’t show up in our standard economic data. Perhaps the top item in this category is the increase in the number of people able to work from home. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, 38 million people worked from home on average day last year. That’s an increase of more than 11 million from before the pandemic.

For these people, life is presumably considerably easier. In addition to the time saved on commuting, they are likely saving thousands of dollars a year on transportation and other costs associated with going to work at an office or other workplace.

In the same vein, telemedicine has become far more widely used. According to the Department of Health and Human Services, 22 percent of the population used telemedicine for a consultation with a healthcare professional in a typical four-week period. Since most people do not see a healthcare professional in any given four-week period, this implies a very large share of medical consultations are now done remotely.

This is a huge savings on time spent traveling to and from hospitals or other medical facilities. The benefits from being able to have a remote consultation are likely to be especially important to people in poor health, who disproportionately are the individuals seeking medical care.

In short, contrary to Nate Cohn’s assessment, there are many clearly identifiable ways in which life has gotten easier that are not picked up in economic statistics. To be fair, he was clearly just speculating in throwing out his life-getting-harder hypothesis, but it does not look like it holds up well under closer scrutiny.

There is a clear disconnect between how people rate the economy (the general economy, not their own economic condition – which most say is good) and standard measures of economic performance. This disconnect has led to a “vibes” vs economic reality debate, with one side arguing that negative news coverage and social media have led people to rate the economy poorly, while the other side argues that weak or declining real incomes explain negative attitudes.

Nate Cohn entered the vibes vs real economic conditions controversy with a unique contribution. He said that even though most standard economic measures, like employment, wages, and income suggest that people are doing pretty well, “factors dragging down consumers aren’t neatly captured by the usual economic statistics.”

“…some basic things have become harder. It’s harder to hire. It’s harder to get a loan. It’s more expensive to buy things. At times it was impossible to buy things because of supply chain shortages. It’s harder to buy a home. It’s harder to sell a home. If you wanted to engage in these kinds of economic activities, you should have done them before the fall of 2021.”

Cohn’s comments here are obviously speculative, he presents no data to support these assertions, but it’s worth considering the idea more carefully.

Some things definitely are harder today than in prior years, like buying and selling a home. With mortgage rates peaking at over 8.0 percent (they are now back under 7.0 percent), sales of existing homes fell by close to one-third from the 2021 pace. This is bad news, but still, the people who are actively looking to buy or sell a home in a given year (around 6 million, typically) are a relatively small share of the population.

Also, if we are looking at the negative story of high-interest rates, we should also look at the positive story that 14 million homeowners refinanced a mortgage during the period of low-interest rates from 2020-2022. Those who refinanced without taking out additional cash saved an average of more than $2,600 a year on interest payments. These savings do not show up in our standard data on income or disposable income.

Cohn tells us that it is harder to hire. This is true, but how many of us are looking to hire people? I suppose if we are looking for people to do work around the house, this could be the case. That is “the hard to get good help” theory of economic malaise.

The obvious flip side of it being harder to hire is that it is easier to find work. Ease of finding work is also not picked up in standard economic statistics and, as a practical matter, there are far more people who would be looking to find work than to hire.

We then have the claim that things are more expensive. That is true, but incomes have grown by more, and this is picked up in our economic statistics.

But then we have the claim that it is harder to buy things. There were certainly shortages of many items in 2021 and even into 2022, making it harder to buy many items. But by 2023, most of these shortages have disappeared. If this were a major factor in people’s economic discontent, we should have seen consumer sentiment improving over the course of the year, instead of deteriorating.

There also is another side to this issue. Online sales have exploded since the pandemic. Online sales accounted for 12.6 percent of retail sales in 2019. They now account for 16.7 percent of retail sales, an increase of more than a third. And this only counts the sales by online distributors, it does not include the growth of Internet sales for brick-and-mortar retailers or the explosion in food delivery from restaurants.

There are other important ways in which life has gotten easier that don’t show up in our standard economic data. Perhaps the top item in this category is the increase in the number of people able to work from home. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, 38 million people worked from home on average day last year. That’s an increase of more than 11 million from before the pandemic.

For these people, life is presumably considerably easier. In addition to the time saved on commuting, they are likely saving thousands of dollars a year on transportation and other costs associated with going to work at an office or other workplace.

In the same vein, telemedicine has become far more widely used. According to the Department of Health and Human Services, 22 percent of the population used telemedicine for a consultation with a healthcare professional in a typical four-week period. Since most people do not see a healthcare professional in any given four-week period, this implies a very large share of medical consultations are now done remotely.

This is a huge savings on time spent traveling to and from hospitals or other medical facilities. The benefits from being able to have a remote consultation are likely to be especially important to people in poor health, who disproportionately are the individuals seeking medical care.

In short, contrary to Nate Cohn’s assessment, there are many clearly identifiable ways in which life has gotten easier that are not picked up in economic statistics. To be fair, he was clearly just speculating in throwing out his life-getting-harder hypothesis, but it does not look like it holds up well under closer scrutiny.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Government-granted patent monopolies have become pretty much sacred in the United States. In fact, when high drug prices become a political issue, most discussion, including from progressives, turns reality on its head. The standard story is that the market creates high drug prices, the issue is whether the government should intervene through some type of negotiation or price control to bring prices down.

Government-granted Patent Monopolies Are the Cause of High-Priced Drugs

In fact, in almost all cases, drugs are cheap to manufacture and distribute. The reason that drugs can be expensive is that the government grants patent monopolies that prevent companies from entering the market.[1] When a single company has a legal monopoly on a drug that is essential to some people’s health or life, they can charge a large amount of money. It is the government-granted monopoly that makes the drug expensive, not the free market.

President Biden proposes to limit the legal monopoly given to at least some drugs, by using the provision of the Bayh-Dole Act that requires inventions that rely on government-funded research be made available at a reasonable price. The Bayh-Dole Act is a measure passed by Congress in 1980 that formalized the process whereby private companies could secure patents on publicly funded research.

It had a huge impact on research generally, but nowhere is its impact clearer than in the case of prescription drugs. From 1960 to 1980, when the bill was passed, spending on prescription drugs was around 0.4 percent of GDP (around $100 billion a year in today’s economy), with no clear upward trend. After the bill was passed spending on prescription drugs began to rise rapidly. It now stands at more than $500 billion, or 2.0 percent of GDP. If we add in non-prescription drugs (the distinction is not necessarily very useful), it comes to $630 billion or 2.3 percent of GDP.

If these drugs were sold in a free market, without patent monopolies or related protections, we would likely be paying less than $100 billion a year. The difference of $530 billion between the patent-protected price and the free market price, comes to more than $4,000 per family.

The issue here is more than just money. People need drugs when they have health problems. This is not a good time to force someone to have to dig up some vast sum of money to pay for a drug to treat cancer or some other serious illness. Even if they are lucky enough to have insurance, no insurer is happy to pay out tens of thousands of dollars for a drug. It is likely to force a patient to jump through all sorts of hoops to get an expensive drug covered. Again, this is not the sort of thing a person with a serious health problem needs.

The high prices are almost entirely a consequence of protection. A recent study found that prices fall by 80-90 percent after a drug has been subjected to a period of generic competition. In the cases of the highest-priced drugs, the drops can be even more dramatic. When the Hepatitis C drug Solvadi was first introduced it sold for $80,000 in the United States for a three-month course of treatment. At the same time, high-quality generic versions were available in India for $900, just over 1.0 percent of the U.S. price.

It would be a struggle for anyone to come with $80,000 to pay for Sovaldi and no insurer is happy to pay that sort of money. The generic price of $900 is a very different story.

The huge gap between the protected price and the free market price also provides an enormous incentive for corruption. Drug companies want to push their drugs as widely as possible, encouraging people to use them even when they may not be the best course of treatment or could even be harmful.

The most dramatic instance of such abuse is the opioid crisis, where Purdue Pharma and other manufacturers paid out billions of dollars in settlements over allegations they deliberately misled physicians and the general public about the addictiveness of the new generation of opioid drugs. The opioid case is extreme in its consequences however, this sort of abuse happens all the time.

Medical journals have to constantly develop new tactics to ensure that the articles they publish are actually written by the people who appear as their authors, and that they have not been paid to put out claims that may not be accurate. In a recent case, intensive lobbying by a drug manufacturer got the FDA to approve an Alzheimer’s drug, Aduhelm, over the objections of its advisory panel. There was little evidence of the drug’s effectiveness and it did have harmful side effects. The drug was slated to sell for $55,000 for a year’s dose.

For these reasons, it is likely that lowering drug prices will actually result in better health outcomes. If there is no one who has a major incentive to mislead the public about the safety and effectiveness of a drug, we are more likely to get accurate information about the usefulness of different drugs for treating various conditions.

Who Pays for Research?

The pharmaceutical industry always screams bloody murder over any measure that will lower drug prices and reduce its profits. They claim that this will be a huge hit to their research spending, and then we won’t get any new drugs.

There will undoubtedly be some negative effects on research spending if profits fall, but the industry hugely overstates the impact. The industry spends roughly $120 billion a year on research and development. This money comes from the gap of more than $500 billion a year between the revenue from selling their drugs and what it costs to manufacture and distribute them.

Over $100 billion of this is profits, but there are many other uses of the money obtained through patent rents. A substantial chunk goes to the pay of CEOs and other top executives. For example, Pfizer’s CEO was paid $33 million last year. He would have been paid considerably less if the company’s drugs were selling at one-fifth of their current price. The bloated pay goes well beyond the CEO, patent rents lead to considerably higher pay for several layers below the top echelon of employees.

In addition, the huge patent rents lead to large payments for marketing drugs. When drugs can be sold at markups of 500 or 1000 percent above their production costs, it makes sense to spend a lot of money trying to promote them widely. For this reason, drug companies spend tens of billions of dollars every year marketing their drugs. This includes not only the ads they run on TV (which had been illegal until a few decades ago) but also money paid to the drug detailers who push the drugs directly to doctors.

Drug companies also pay out vast sums to lawyers, as intellectual property law is one of the most lucrative areas of law. If you’re suing someone over a patent worth billions of dollars, it is a good investment to spend hundreds of millions pushing your case. And, there are the billions of dollars they have to pay out when they lose a case, as was the situation with Purdue Pharma and the other major opioid makers.

All of these payments can be reduced, rather than cutting research spending, when the pharmaceutical industry’s profits dip as a result of lower prices. There is also another area where savings can be found rather than reducing important research into new drugs.

Much of the industry’s spending goes to drugs that largely duplicate existing drugs. The logic is that if one company is earning large patent rents on a particular drug, say the weight loss drug Wegovy, it makes sense from the standpoint of maximizing profit to try to produce a competitor that can share in these rents.

This is actually desirable in a world where drugs are selling at patent-protected prices. Having two, three, or four drugs that are largely similar, all of which have patent protection, will still help to bring prices down. There is also likely to be some health benefit, since patients react differently to the same drug, so having the option to take a different drug will be valuable to some patients. However, as a general rule, research dollars would likely be better spent trying to develop drugs for conditions where no effective treatment currently exists rather than trying to duplicate the function of existing drugs in order to get a share of patent rents.

In 2021, the most recent year for which the data are available, the FDA rated more than 56 percent of its drug reviews as “standard,” meaning that the drugs did not represent a qualitative breakthrough over existing drugs already on the market. It would not in general be a major loss to public health if the research spending on these duplicative drugs was reduced as a result of lower drug prices and profit margins.

Government Spending on Research

But even if the reduction in industry profits will only be reflected in a limited way in reduced research spending, there is no doubt that the companies will be spending somewhat less on money on developing new drugs. This doesn’t have to mean a reduction in total spending on research.

The federal government already spends well over $50 billion a year on biomedical research, primarily through the National Institutes of Health, but also through BARDA, the CDC and a number of other government agencies. This money primarily goes to more basic research, but many drugs have been developed on public money and often tested as well. The most famous recent example was the Moderna COVID vaccine, where Operation Warp Speed paid for both the development and the clinical trials needed for the vaccine’s approval, but there have been many others.

Public funding can serve as a substitute for industry funding. Recent research indicates that increased NIH funding can be a very effective substitute for industry funding. In fact, it suggests that dollar for dollar, NIH funding may be far more effective, with a 10 percent increase in funding (roughly $5 billion a year at present) leading to a 4.5 percent increase in the number of drugs developed. This result, taken crudely, implies that for $110 billion in additional spending, we could fully replace the spending done by the industry, with no loss in the number of new drugs developed.

Of course, the world is far more complicated than this sort of simple multiplication would imply, but most of the complications likely mean the cost of replacing industry research would likely be lower rather than higher. To start with, if we were financing research with the goal of advancing health rather than seeking patent rents, we would likely see much less money wasted in duplicative research.

Again, not all of this money is wasted. It is very often helpful to have a second or third drug to treat a condition, since people react differently to drugs and some drugs interact badly with other drugs a patient may be taking. But the search for patent rents is likely to misdirect much research spending compared to a scenario where the focus is public health.

A second reason we may get more health benefits per buck with direct publicly supported research is that there may be many instances where non-patentable items offer the greatest health benefit. For example, there is some research indicating that vitamin deficiencies may be an important factor in many conditions. Drug companies have little incentive to research this possibility since they can’t get a patent on vitamins that have been known for many decades.

The same applies to older off-patent drugs. If there is some evidence Aspirin can provide important benefits in treating a condition, Pfizer or Merck is not going to spend large sums exploring that possibility. If it turns out to be true, they will not be able to recoup their research expenses selling a drug that has long been available as a cheap generic.

But the most important reason that publicly funded research might be more effective on a per-dollar basis is that we can make openness a condition of getting funding. This means that rather than having an incentive to squirrel away findings, in order to avoid allowing a competitor to get an advantage, we can require that the results of publicly funded research be posted on the Internet as soon as practical.

This means that all researchers can benefit from quickly learning of new breakthroughs as well as being warned off dead ends. This openness requirement would also largely eliminate the risk of drug companies misrepresenting research findings to push their drugs as widely as possible.

Not only would we be removing the incentive by taking away the patent monopoly, we would also be removing the opportunity, since the community of researchers would all have access to the same research. We can’t eliminate all mistakes – some mistakes are inevitable – but we can prevent the sort of deliberate misrepresentation of evidence that had such terrible consequences in the opioid crisis and in many other situations.

Patent Monopolies and Inequality

It is common for people in policy circles to assert that the enormous increase in inequality over the last half century was primarily the result of technology. The story is that technology has developed in a way that has benefited people with more education and disadvantaged those with limited education. This is not true.

It is more than a bit absurd to claim that patent monopolies and related protections are necessary for the development of new drugs or to achieve progress in other areas, and then claim that inequality is the result of technology. Our rules on patents and other forms of intellectual property are policy matters, they are not determined by technology.

This point matters hugely in discussions of inequality, since it is policy that determines who benefits from technology and how much. We saw this clearly in the case of Moderna and its development of a COVID vaccine. The contract it signed with the government both paid for the development of the vaccine and then allowed Moderna to keep control of the vaccine.

As a result of this contract, Moderna is selling its boosters for well over $100 a shot, even though it would likely only cost it around $5 a shot to produce and distribute the vaccine. The Moderna contract allowed the company to generate at least five billionaires by the summer of 2022.

The Moderna contract is an extreme case, but it does provide a clear example. How we structure laws around patent monopolies and other protections determines the winners from technology.

It is obviously convenient for the gainers from this upward redistribution to pretend that it was just a natural outcome from technology, but it is not true. If we write the rules differently, we can have much less inequality.

Where Do the Administration’s Bayh-Dole Measures Get Us?

I have long argued for looking to displace the system of patent-supported research for prescription drugs with one of direct public funding. My preferred route is a system of long-term prime contracts, loosely modeled on the sort of prime contracts that the Defense Department awards for military research, where companies would engage in a process of competitive bidding for research in specific areas, such as cancer or heart disease. (I outline this in Chapter 5 of Rigged [it’s free].)

The Biden administration’s proposal is not my proposal for radically overhauling the system of financing the development of prescription drugs. It does, however, raise the issue of how much we will allow pharmaceutical companies to benefit from the patent monopolies we grant them at the expense of the general public.

It allows the government to take advantage of the provision in the Bayh-Dole Act requiring that innovations based on government-funded research be available to the public at a reasonable price. This is a big step forward, since it means that we will not hand drug companies a monopoly on life-saving drugs and then let them charge patients (or insurers or the government) whatever price they feel like. This can save the public and the government billions of dollars each year.

While this measure is important in establishing that patent monopolies are not absolute, it is limited in that it only applies to a limited set of drugs, only those where government-funded research played a direct role in its development. That may seem fair in some ways, but drug companies often don’t acknowledge that they relied on government research in developing a product.

If a drug company relied on another company’s research in developing a drug, it can count on a patent infringement suit, but the government is generally not aggressive in forcing companies to list government patents that played a role in developing a product. The executive order also does not give clear guidance on what constitutes reasonable pricing. It could, for example, have specified that a reasonable price is some average of prices charged in other wealthy countries, like Germany and Canada, but it backed away from this step.[2]

There are of course other modest steps that the Biden administration could take to lower drug prices, some of which it already has. For one, it capped the out-of-pocket payments for insulin, although this has the government picking up the tab, so that is not a measure that costs the pharmaceutical industry money. It is also moving to negotiate the prices that Medicare pays for a number of important drugs, this will save the program and beneficiaries billions of dollars in coming years.

But there are also limited steps that it could take that would push the agenda further. Drs. Peter Hotez and Maria Elena Bottazzi and their team at Texas Children’s Hospital developed an effective open-source COVID vaccine. This vaccine, Corbevax has already been used by over 100 million people in India, Indonesia, and elsewhere.

If this vaccine was approved by the FDA, it would mean that people would have a cheap alternative (likely less than $5 a shot) to the vaccines now on the market, which are selling for over $100 a shot. If the vaccine were available here, it would also mean that people have an alternative to the mRNA vaccines produced by Moderna and Pfizer. While there is little basis for the fears of mRNA technology, if these fears prevent people from getting a vaccine that could protect them from COVID, we should be allowing them an alternative.

Getting a cheap vaccine developed outside the patent system would also provide proof of concept. No one cares that I or others claim that we can produce drugs or vaccines without relying on patent monopolies, they need to see proof in the form of facts on the ground that we can have effective products that don’t depend on these monopolies. Corbevax can be an important fact on the ground. (Many people may not be aware of the enormous savings with this vaccine, since in most cases, the government or private insurers will pick up the cost of COVID boosters.)

A Very Important Step

It is always possible to complain that a particular measure does not go as far as it should, but it is very rare that major change is brought about by a single bill or executive order from a president. The question is whether the measure is a step forward and if it opens the door for future progress.

By this standard, the answer is certainly yes. We can think of this executive order as being comparable to the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA). The provisions of the IRA are nowhere near large enough to address the problem of global warming, but they are a huge foot in the door. In the same way, President Biden’s actions on Bayh-Dole are an important step in reining in drug prices and creating a path for further actions in the future.

[1] There are other forms of exclusivity that can be as important as patent monopolies in blocking competition, most notably “data exclusivity.” This means that when a drug company produces data showing a particular drug is safe and effective, another company cannot rely on this data to establish that its own drug is also safe and effective, even if it can be shown to be chemically the same or similar in the case of biological drugs.

[2] This write-up from Knowledge Economy International provides useful background on some of the issues raised by the Biden Administration’s executive order.

Government-granted patent monopolies have become pretty much sacred in the United States. In fact, when high drug prices become a political issue, most discussion, including from progressives, turns reality on its head. The standard story is that the market creates high drug prices, the issue is whether the government should intervene through some type of negotiation or price control to bring prices down.

Government-granted Patent Monopolies Are the Cause of High-Priced Drugs

In fact, in almost all cases, drugs are cheap to manufacture and distribute. The reason that drugs can be expensive is that the government grants patent monopolies that prevent companies from entering the market.[1] When a single company has a legal monopoly on a drug that is essential to some people’s health or life, they can charge a large amount of money. It is the government-granted monopoly that makes the drug expensive, not the free market.

President Biden proposes to limit the legal monopoly given to at least some drugs, by using the provision of the Bayh-Dole Act that requires inventions that rely on government-funded research be made available at a reasonable price. The Bayh-Dole Act is a measure passed by Congress in 1980 that formalized the process whereby private companies could secure patents on publicly funded research.

It had a huge impact on research generally, but nowhere is its impact clearer than in the case of prescription drugs. From 1960 to 1980, when the bill was passed, spending on prescription drugs was around 0.4 percent of GDP (around $100 billion a year in today’s economy), with no clear upward trend. After the bill was passed spending on prescription drugs began to rise rapidly. It now stands at more than $500 billion, or 2.0 percent of GDP. If we add in non-prescription drugs (the distinction is not necessarily very useful), it comes to $630 billion or 2.3 percent of GDP.

If these drugs were sold in a free market, without patent monopolies or related protections, we would likely be paying less than $100 billion a year. The difference of $530 billion between the patent-protected price and the free market price, comes to more than $4,000 per family.

The issue here is more than just money. People need drugs when they have health problems. This is not a good time to force someone to have to dig up some vast sum of money to pay for a drug to treat cancer or some other serious illness. Even if they are lucky enough to have insurance, no insurer is happy to pay out tens of thousands of dollars for a drug. It is likely to force a patient to jump through all sorts of hoops to get an expensive drug covered. Again, this is not the sort of thing a person with a serious health problem needs.

The high prices are almost entirely a consequence of protection. A recent study found that prices fall by 80-90 percent after a drug has been subjected to a period of generic competition. In the cases of the highest-priced drugs, the drops can be even more dramatic. When the Hepatitis C drug Solvadi was first introduced it sold for $80,000 in the United States for a three-month course of treatment. At the same time, high-quality generic versions were available in India for $900, just over 1.0 percent of the U.S. price.

It would be a struggle for anyone to come with $80,000 to pay for Sovaldi and no insurer is happy to pay that sort of money. The generic price of $900 is a very different story.

The huge gap between the protected price and the free market price also provides an enormous incentive for corruption. Drug companies want to push their drugs as widely as possible, encouraging people to use them even when they may not be the best course of treatment or could even be harmful.

The most dramatic instance of such abuse is the opioid crisis, where Purdue Pharma and other manufacturers paid out billions of dollars in settlements over allegations they deliberately misled physicians and the general public about the addictiveness of the new generation of opioid drugs. The opioid case is extreme in its consequences however, this sort of abuse happens all the time.

Medical journals have to constantly develop new tactics to ensure that the articles they publish are actually written by the people who appear as their authors, and that they have not been paid to put out claims that may not be accurate. In a recent case, intensive lobbying by a drug manufacturer got the FDA to approve an Alzheimer’s drug, Aduhelm, over the objections of its advisory panel. There was little evidence of the drug’s effectiveness and it did have harmful side effects. The drug was slated to sell for $55,000 for a year’s dose.

For these reasons, it is likely that lowering drug prices will actually result in better health outcomes. If there is no one who has a major incentive to mislead the public about the safety and effectiveness of a drug, we are more likely to get accurate information about the usefulness of different drugs for treating various conditions.

Who Pays for Research?

The pharmaceutical industry always screams bloody murder over any measure that will lower drug prices and reduce its profits. They claim that this will be a huge hit to their research spending, and then we won’t get any new drugs.

There will undoubtedly be some negative effects on research spending if profits fall, but the industry hugely overstates the impact. The industry spends roughly $120 billion a year on research and development. This money comes from the gap of more than $500 billion a year between the revenue from selling their drugs and what it costs to manufacture and distribute them.

Over $100 billion of this is profits, but there are many other uses of the money obtained through patent rents. A substantial chunk goes to the pay of CEOs and other top executives. For example, Pfizer’s CEO was paid $33 million last year. He would have been paid considerably less if the company’s drugs were selling at one-fifth of their current price. The bloated pay goes well beyond the CEO, patent rents lead to considerably higher pay for several layers below the top echelon of employees.

In addition, the huge patent rents lead to large payments for marketing drugs. When drugs can be sold at markups of 500 or 1000 percent above their production costs, it makes sense to spend a lot of money trying to promote them widely. For this reason, drug companies spend tens of billions of dollars every year marketing their drugs. This includes not only the ads they run on TV (which had been illegal until a few decades ago) but also money paid to the drug detailers who push the drugs directly to doctors.

Drug companies also pay out vast sums to lawyers, as intellectual property law is one of the most lucrative areas of law. If you’re suing someone over a patent worth billions of dollars, it is a good investment to spend hundreds of millions pushing your case. And, there are the billions of dollars they have to pay out when they lose a case, as was the situation with Purdue Pharma and the other major opioid makers.

All of these payments can be reduced, rather than cutting research spending, when the pharmaceutical industry’s profits dip as a result of lower prices. There is also another area where savings can be found rather than reducing important research into new drugs.

Much of the industry’s spending goes to drugs that largely duplicate existing drugs. The logic is that if one company is earning large patent rents on a particular drug, say the weight loss drug Wegovy, it makes sense from the standpoint of maximizing profit to try to produce a competitor that can share in these rents.

This is actually desirable in a world where drugs are selling at patent-protected prices. Having two, three, or four drugs that are largely similar, all of which have patent protection, will still help to bring prices down. There is also likely to be some health benefit, since patients react differently to the same drug, so having the option to take a different drug will be valuable to some patients. However, as a general rule, research dollars would likely be better spent trying to develop drugs for conditions where no effective treatment currently exists rather than trying to duplicate the function of existing drugs in order to get a share of patent rents.

In 2021, the most recent year for which the data are available, the FDA rated more than 56 percent of its drug reviews as “standard,” meaning that the drugs did not represent a qualitative breakthrough over existing drugs already on the market. It would not in general be a major loss to public health if the research spending on these duplicative drugs was reduced as a result of lower drug prices and profit margins.

Government Spending on Research

But even if the reduction in industry profits will only be reflected in a limited way in reduced research spending, there is no doubt that the companies will be spending somewhat less on money on developing new drugs. This doesn’t have to mean a reduction in total spending on research.

The federal government already spends well over $50 billion a year on biomedical research, primarily through the National Institutes of Health, but also through BARDA, the CDC and a number of other government agencies. This money primarily goes to more basic research, but many drugs have been developed on public money and often tested as well. The most famous recent example was the Moderna COVID vaccine, where Operation Warp Speed paid for both the development and the clinical trials needed for the vaccine’s approval, but there have been many others.

Public funding can serve as a substitute for industry funding. Recent research indicates that increased NIH funding can be a very effective substitute for industry funding. In fact, it suggests that dollar for dollar, NIH funding may be far more effective, with a 10 percent increase in funding (roughly $5 billion a year at present) leading to a 4.5 percent increase in the number of drugs developed. This result, taken crudely, implies that for $110 billion in additional spending, we could fully replace the spending done by the industry, with no loss in the number of new drugs developed.

Of course, the world is far more complicated than this sort of simple multiplication would imply, but most of the complications likely mean the cost of replacing industry research would likely be lower rather than higher. To start with, if we were financing research with the goal of advancing health rather than seeking patent rents, we would likely see much less money wasted in duplicative research.

Again, not all of this money is wasted. It is very often helpful to have a second or third drug to treat a condition, since people react differently to drugs and some drugs interact badly with other drugs a patient may be taking. But the search for patent rents is likely to misdirect much research spending compared to a scenario where the focus is public health.

A second reason we may get more health benefits per buck with direct publicly supported research is that there may be many instances where non-patentable items offer the greatest health benefit. For example, there is some research indicating that vitamin deficiencies may be an important factor in many conditions. Drug companies have little incentive to research this possibility since they can’t get a patent on vitamins that have been known for many decades.

The same applies to older off-patent drugs. If there is some evidence Aspirin can provide important benefits in treating a condition, Pfizer or Merck is not going to spend large sums exploring that possibility. If it turns out to be true, they will not be able to recoup their research expenses selling a drug that has long been available as a cheap generic.

But the most important reason that publicly funded research might be more effective on a per-dollar basis is that we can make openness a condition of getting funding. This means that rather than having an incentive to squirrel away findings, in order to avoid allowing a competitor to get an advantage, we can require that the results of publicly funded research be posted on the Internet as soon as practical.

This means that all researchers can benefit from quickly learning of new breakthroughs as well as being warned off dead ends. This openness requirement would also largely eliminate the risk of drug companies misrepresenting research findings to push their drugs as widely as possible.

Not only would we be removing the incentive by taking away the patent monopoly, we would also be removing the opportunity, since the community of researchers would all have access to the same research. We can’t eliminate all mistakes – some mistakes are inevitable – but we can prevent the sort of deliberate misrepresentation of evidence that had such terrible consequences in the opioid crisis and in many other situations.

Patent Monopolies and Inequality

It is common for people in policy circles to assert that the enormous increase in inequality over the last half century was primarily the result of technology. The story is that technology has developed in a way that has benefited people with more education and disadvantaged those with limited education. This is not true.

It is more than a bit absurd to claim that patent monopolies and related protections are necessary for the development of new drugs or to achieve progress in other areas, and then claim that inequality is the result of technology. Our rules on patents and other forms of intellectual property are policy matters, they are not determined by technology.

This point matters hugely in discussions of inequality, since it is policy that determines who benefits from technology and how much. We saw this clearly in the case of Moderna and its development of a COVID vaccine. The contract it signed with the government both paid for the development of the vaccine and then allowed Moderna to keep control of the vaccine.

As a result of this contract, Moderna is selling its boosters for well over $100 a shot, even though it would likely only cost it around $5 a shot to produce and distribute the vaccine. The Moderna contract allowed the company to generate at least five billionaires by the summer of 2022.

The Moderna contract is an extreme case, but it does provide a clear example. How we structure laws around patent monopolies and other protections determines the winners from technology.

It is obviously convenient for the gainers from this upward redistribution to pretend that it was just a natural outcome from technology, but it is not true. If we write the rules differently, we can have much less inequality.

Where Do the Administration’s Bayh-Dole Measures Get Us?

I have long argued for looking to displace the system of patent-supported research for prescription drugs with one of direct public funding. My preferred route is a system of long-term prime contracts, loosely modeled on the sort of prime contracts that the Defense Department awards for military research, where companies would engage in a process of competitive bidding for research in specific areas, such as cancer or heart disease. (I outline this in Chapter 5 of Rigged [it’s free].)

The Biden administration’s proposal is not my proposal for radically overhauling the system of financing the development of prescription drugs. It does, however, raise the issue of how much we will allow pharmaceutical companies to benefit from the patent monopolies we grant them at the expense of the general public.

It allows the government to take advantage of the provision in the Bayh-Dole Act requiring that innovations based on government-funded research be available to the public at a reasonable price. This is a big step forward, since it means that we will not hand drug companies a monopoly on life-saving drugs and then let them charge patients (or insurers or the government) whatever price they feel like. This can save the public and the government billions of dollars each year.

While this measure is important in establishing that patent monopolies are not absolute, it is limited in that it only applies to a limited set of drugs, only those where government-funded research played a direct role in its development. That may seem fair in some ways, but drug companies often don’t acknowledge that they relied on government research in developing a product.

If a drug company relied on another company’s research in developing a drug, it can count on a patent infringement suit, but the government is generally not aggressive in forcing companies to list government patents that played a role in developing a product. The executive order also does not give clear guidance on what constitutes reasonable pricing. It could, for example, have specified that a reasonable price is some average of prices charged in other wealthy countries, like Germany and Canada, but it backed away from this step.[2]

There are of course other modest steps that the Biden administration could take to lower drug prices, some of which it already has. For one, it capped the out-of-pocket payments for insulin, although this has the government picking up the tab, so that is not a measure that costs the pharmaceutical industry money. It is also moving to negotiate the prices that Medicare pays for a number of important drugs, this will save the program and beneficiaries billions of dollars in coming years.

But there are also limited steps that it could take that would push the agenda further. Drs. Peter Hotez and Maria Elena Bottazzi and their team at Texas Children’s Hospital developed an effective open-source COVID vaccine. This vaccine, Corbevax has already been used by over 100 million people in India, Indonesia, and elsewhere.

If this vaccine was approved by the FDA, it would mean that people would have a cheap alternative (likely less than $5 a shot) to the vaccines now on the market, which are selling for over $100 a shot. If the vaccine were available here, it would also mean that people have an alternative to the mRNA vaccines produced by Moderna and Pfizer. While there is little basis for the fears of mRNA technology, if these fears prevent people from getting a vaccine that could protect them from COVID, we should be allowing them an alternative.

Getting a cheap vaccine developed outside the patent system would also provide proof of concept. No one cares that I or others claim that we can produce drugs or vaccines without relying on patent monopolies, they need to see proof in the form of facts on the ground that we can have effective products that don’t depend on these monopolies. Corbevax can be an important fact on the ground. (Many people may not be aware of the enormous savings with this vaccine, since in most cases, the government or private insurers will pick up the cost of COVID boosters.)

A Very Important Step

It is always possible to complain that a particular measure does not go as far as it should, but it is very rare that major change is brought about by a single bill or executive order from a president. The question is whether the measure is a step forward and if it opens the door for future progress.

By this standard, the answer is certainly yes. We can think of this executive order as being comparable to the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA). The provisions of the IRA are nowhere near large enough to address the problem of global warming, but they are a huge foot in the door. In the same way, President Biden’s actions on Bayh-Dole are an important step in reining in drug prices and creating a path for further actions in the future.

[1] There are other forms of exclusivity that can be as important as patent monopolies in blocking competition, most notably “data exclusivity.” This means that when a drug company produces data showing a particular drug is safe and effective, another company cannot rely on this data to establish that its own drug is also safe and effective, even if it can be shown to be chemically the same or similar in the case of biological drugs.

[2] This write-up from Knowledge Economy International provides useful background on some of the issues raised by the Biden Administration’s executive order.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

New York Times columnist Steve Rattner told readers that people think the economy is terrible and then gave some not very plausible reasons why. As Rattner explains:

“As I’ve engaged with my many interlocutors, I’ve concluded that voters have valid reasons for their negativity. In my view, blame two culprits: one immediate and impacting everybody, and another that particularly affects young people and is coming into view like a giant iceberg. Both sit atop the leaderboard of reasons for the sour national mood.”

Okay, first on Rattner’s list, people care about inflation, not jobs.

“To them, higher prices just means less spending power. A recent Blueprint/YouGov poll on the economy found that just 7 percent of respondents were principally concerned about the availability of jobs, while 64 percent were most worried about prices.

“The problem for President Biden is that by a margin of 43 percent to 23 percent, voters believe that he is more focused on jobs.”

Let’s apply a little common sense here. Let’s imagine that people care about both prices and jobs. Right now, because of Biden administration policies, unemployment is very low, so people have jobs. That means they probably are not worried about jobs.

It’s sort of like if you had a patient with a heart problem and a bad knee. After the doctor prescribes a medication that addresses the heart problem, it’s likely that they will be primarily worried about their bad knee. That doesn’t mean they didn’t care about their heart problem, it just means that for the time being, their heart problem is under control.

We also get the refrain that people expect prices to come down. We keep hearing that line in the media. Suppose some number of people expect pigs to fly.

Would we see the line repeated endlessly that people expect pigs to fly? My guess is that we would see some number of pieces ridiculing the fact that some people are expecting the impossible. Then the media would stop reporting it, rather than what we see now where the media continually repeats the idea that people expect prices to go down.

For what is worth, virtually no one expected prices to go back down in the 1980s after the 1970s inflation. And, a point that Rattner neglects to mention, wages have been outpacing prices, so people’s purchasing power has been increasing. That was not true in the 1980s when the media were celebrating the “Reagan boom.”

Then we get to the long-term story.

“The longer-term issue that bubbles up from polls and other data is deep pessimism about the future. Uncharacteristically, a stunning majority of Americans now believe that the next generation is likely to have a lower standard of living.

“A Wall Street Journal-NORC poll from March found that just 21 percent of respondents felt confident that life for their children’s generation will be better, matching the record low since this question was first asked.”

Actually, pessimism about the future is not uncharacteristic. A poll taken in March of 1998, when the economy was in the middle of a five year long boom, found that the number of people who thought that life would be better in the next century was tied with the number of people who thought it would be worse, at 36 percent each.

Rattner’s next step in making his case is that more young people are living at home.

“Consider one marker of generational progress: moving out. Nearly half of all Americans aged 18-29 live at home with their parents, the highest share since the Great Depression.”

Rattner is playing more than a bit fast and loose here. The share of young people living at home was rising through most of the last decade. It jumped during the pandemic, and has been trailing downward in the last year.

He also tells us that high house prices and high interest rates make it difficult for young people to buy homes. That’s true, but until interest rates jumped last year, the number of young people owning homes was increasing and it’s still above pre-pandemic levels. Perhaps Rattner thinks high rates will persist indefinitely, but he is very much in the minority on that point.

Then we get to the big kicker:

“Even more fundamentally, voters — admittedly, not economists — may deserve credit for at least subconsciously comprehending two immense longer-term challenges: lagging productivity and a huge and fast-rising national debt.”

It’s a bit hard to believe that anyone who has followed the economy for the last five decades would cite slow productivity growth as a reason for the current pessimism about the economy. We’ve had slow productivity growth for most of the last half century, why is it just now bothering young people?

The other irony of this comment is that we just got a report showing that productivity grew at an incredibly fast 5.2 percent annual rate in the third quarter. No one expects this pace to continue, and the productivity data are highly erratic, but it is a bit bizarre right now to be claiming that slow productivity growth is the reason for people’s discontent.

Then we get the national debt. The fact is, no one has any clue what the size of the national debt is. If it were half its current size it would still sound like a huge number to people. It’s pretty hard to believe that many people have looked carefully and thought about the consequences of the national debt, although hearing politicians and pundits whine about the debt may have scared them.

If they did want to worry about something that would cost them real money, they might worry about the trillions of dollars they will pay out in future years to drug companies, medical equipment suppliers, and other companies that have government-granted patent and copyright monopolies. But, the recipients of these rents are probably Steven Rattner’s friends, and they don’t allow for such things to be talked about in the New York Times anyhow.

Ironically, Rattner doesn’t mention global warming. The damage that we are doing to the planet gives young people very serious grounds to be worried about the future. But I suppose preventing environmental destruction doesn’t matter to Rattner.

Anyhow, it is possible to make a case in the NYT that things are really bad right now and people should be worried about the economy. It may not be a very solid case, but who cares?

New York Times columnist Steve Rattner told readers that people think the economy is terrible and then gave some not very plausible reasons why. As Rattner explains:

“As I’ve engaged with my many interlocutors, I’ve concluded that voters have valid reasons for their negativity. In my view, blame two culprits: one immediate and impacting everybody, and another that particularly affects young people and is coming into view like a giant iceberg. Both sit atop the leaderboard of reasons for the sour national mood.”

Okay, first on Rattner’s list, people care about inflation, not jobs.

“To them, higher prices just means less spending power. A recent Blueprint/YouGov poll on the economy found that just 7 percent of respondents were principally concerned about the availability of jobs, while 64 percent were most worried about prices.

“The problem for President Biden is that by a margin of 43 percent to 23 percent, voters believe that he is more focused on jobs.”

Let’s apply a little common sense here. Let’s imagine that people care about both prices and jobs. Right now, because of Biden administration policies, unemployment is very low, so people have jobs. That means they probably are not worried about jobs.

It’s sort of like if you had a patient with a heart problem and a bad knee. After the doctor prescribes a medication that addresses the heart problem, it’s likely that they will be primarily worried about their bad knee. That doesn’t mean they didn’t care about their heart problem, it just means that for the time being, their heart problem is under control.

We also get the refrain that people expect prices to come down. We keep hearing that line in the media. Suppose some number of people expect pigs to fly.

Would we see the line repeated endlessly that people expect pigs to fly? My guess is that we would see some number of pieces ridiculing the fact that some people are expecting the impossible. Then the media would stop reporting it, rather than what we see now where the media continually repeats the idea that people expect prices to go down.

For what is worth, virtually no one expected prices to go back down in the 1980s after the 1970s inflation. And, a point that Rattner neglects to mention, wages have been outpacing prices, so people’s purchasing power has been increasing. That was not true in the 1980s when the media were celebrating the “Reagan boom.”

Then we get to the long-term story.

“The longer-term issue that bubbles up from polls and other data is deep pessimism about the future. Uncharacteristically, a stunning majority of Americans now believe that the next generation is likely to have a lower standard of living.

“A Wall Street Journal-NORC poll from March found that just 21 percent of respondents felt confident that life for their children’s generation will be better, matching the record low since this question was first asked.”

Actually, pessimism about the future is not uncharacteristic. A poll taken in March of 1998, when the economy was in the middle of a five year long boom, found that the number of people who thought that life would be better in the next century was tied with the number of people who thought it would be worse, at 36 percent each.

Rattner’s next step in making his case is that more young people are living at home.

“Consider one marker of generational progress: moving out. Nearly half of all Americans aged 18-29 live at home with their parents, the highest share since the Great Depression.”

Rattner is playing more than a bit fast and loose here. The share of young people living at home was rising through most of the last decade. It jumped during the pandemic, and has been trailing downward in the last year.

He also tells us that high house prices and high interest rates make it difficult for young people to buy homes. That’s true, but until interest rates jumped last year, the number of young people owning homes was increasing and it’s still above pre-pandemic levels. Perhaps Rattner thinks high rates will persist indefinitely, but he is very much in the minority on that point.

Then we get to the big kicker:

“Even more fundamentally, voters — admittedly, not economists — may deserve credit for at least subconsciously comprehending two immense longer-term challenges: lagging productivity and a huge and fast-rising national debt.”

It’s a bit hard to believe that anyone who has followed the economy for the last five decades would cite slow productivity growth as a reason for the current pessimism about the economy. We’ve had slow productivity growth for most of the last half century, why is it just now bothering young people?

The other irony of this comment is that we just got a report showing that productivity grew at an incredibly fast 5.2 percent annual rate in the third quarter. No one expects this pace to continue, and the productivity data are highly erratic, but it is a bit bizarre right now to be claiming that slow productivity growth is the reason for people’s discontent.

Then we get the national debt. The fact is, no one has any clue what the size of the national debt is. If it were half its current size it would still sound like a huge number to people. It’s pretty hard to believe that many people have looked carefully and thought about the consequences of the national debt, although hearing politicians and pundits whine about the debt may have scared them.

If they did want to worry about something that would cost them real money, they might worry about the trillions of dollars they will pay out in future years to drug companies, medical equipment suppliers, and other companies that have government-granted patent and copyright monopolies. But, the recipients of these rents are probably Steven Rattner’s friends, and they don’t allow for such things to be talked about in the New York Times anyhow.

Ironically, Rattner doesn’t mention global warming. The damage that we are doing to the planet gives young people very serious grounds to be worried about the future. But I suppose preventing environmental destruction doesn’t matter to Rattner.

Anyhow, it is possible to make a case in the NYT that things are really bad right now and people should be worried about the economy. It may not be a very solid case, but who cares?

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The NYT had an interesting column today on the growing problem of drug shortages by Emily Tucker. The piece made several important points, but one of them could use a bit more attention.

Tucker notes that a resilient supply chain is not necessarily a domestic supply chain. This is exactly right, but the point deserves far more emphasis than it is given in this piece.

At the height of the pandemic there were shortages of a wide range of items, as demand increased and production was often curtailed due to pandemic conditions. This led to a call for increased domestic sourcing.

Some of this effort was badly misplaced, as stockpiling failings were often treated as supply chain issues. The lack of availability of masks and other protective gear was a stockpile problem, not a supply chain problem.

Even if all our masks were produced in Ohio, we could not get the hundreds of millions of masks needed at the start of the pandemic. It takes time to produce a huge number of masks and large volumes of protective gear more generally. These should have been stockpiled.

The fact that the country did not have a substantial stockpile at the start of the pandemic was a major failing of the Trump administration. This made it harder to curtail the spread of the disease and needlessly exposed many healthcare workers at a time when there were no vaccines or effective treatments.

Part of the problem with drugs in short supply is that many have limited markets. If a drug is designed to treat a relatively rare disease, there will not be an incentive for a company to have large amounts of backup capacity, or to spend a lot of money ensuring the quality of its manufacturing process, once it is available as a low-priced generic.

However, if the drug is being produced for a worldwide market, and not just the U.S. market, it is more likely that there will be several manufacturers producing any given drug. In that scenario, there will be a higher probability that one company’s output can be replaced by competitors, if it is forced to temporarily stop operating due to mechanical problems or quality control issues.

For this reason, it is important that we look to make the market as large as possible. This means removing barriers, other than necessary quality controls, to imports and encouraging other countries to do the same. In this story, a resilient supply chain is an international supply chain that encompasses as large a share of the world as possible. Restricting ourselves to domestic producers is the wrong way to go.

The NYT had an interesting column today on the growing problem of drug shortages by Emily Tucker. The piece made several important points, but one of them could use a bit more attention.

Tucker notes that a resilient supply chain is not necessarily a domestic supply chain. This is exactly right, but the point deserves far more emphasis than it is given in this piece.

At the height of the pandemic there were shortages of a wide range of items, as demand increased and production was often curtailed due to pandemic conditions. This led to a call for increased domestic sourcing.

Some of this effort was badly misplaced, as stockpiling failings were often treated as supply chain issues. The lack of availability of masks and other protective gear was a stockpile problem, not a supply chain problem.

Even if all our masks were produced in Ohio, we could not get the hundreds of millions of masks needed at the start of the pandemic. It takes time to produce a huge number of masks and large volumes of protective gear more generally. These should have been stockpiled.

The fact that the country did not have a substantial stockpile at the start of the pandemic was a major failing of the Trump administration. This made it harder to curtail the spread of the disease and needlessly exposed many healthcare workers at a time when there were no vaccines or effective treatments.

Part of the problem with drugs in short supply is that many have limited markets. If a drug is designed to treat a relatively rare disease, there will not be an incentive for a company to have large amounts of backup capacity, or to spend a lot of money ensuring the quality of its manufacturing process, once it is available as a low-priced generic.

However, if the drug is being produced for a worldwide market, and not just the U.S. market, it is more likely that there will be several manufacturers producing any given drug. In that scenario, there will be a higher probability that one company’s output can be replaced by competitors, if it is forced to temporarily stop operating due to mechanical problems or quality control issues.

For this reason, it is important that we look to make the market as large as possible. This means removing barriers, other than necessary quality controls, to imports and encouraging other countries to do the same. In this story, a resilient supply chain is an international supply chain that encompasses as large a share of the world as possible. Restricting ourselves to domestic producers is the wrong way to go.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

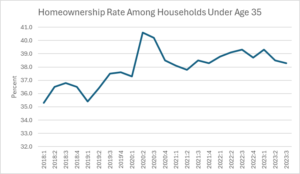

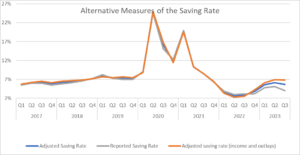

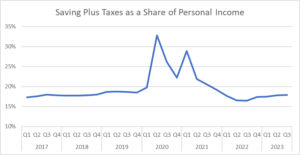

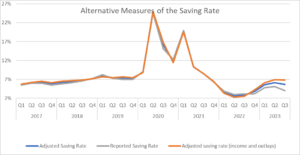

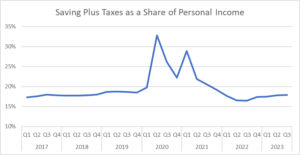

The reported saving rate has fallen sharply from its pandemic peaks, causing many commentators to speculate that people are running out of savings. At first glance, that is what the data show, with the saving rate for the most recent quarter coming in at 4.0 percent. That is up somewhat from the 3.3 percent rate of 2022, but down sharply from the double-digit rates of 2021, and well below the 7.0 percent plus rate we saw just before the pandemic. But there are some complicating factors that could change the picture.

National Income Versus Gross Domestic Product: The Mystery of the Statistical Discrepancy

In principle, we can measure gross domestic product on either the income side, adding up wages, rents, profits, and other forms of income or measure it on the output side, summing consumption, investment, government spending and net exports. We should get the same number either way, every dollar we spend buying things is income for someone.