There is a standard tale of politics where conservatives want to leave things to the market, whereas the left want a big role for government. The right likes to tell this story because it advantages them politically, since most people tend to have a positive view of the market. The left likes to tell it because they are not very good at politics and have an aversion to serious thinking.

The Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) bailout is yet another great example of how the right is just fine with government intervention, as long as the purpose is making the rich richer. Left to the market, the outcome in this case was clear. The FDIC guaranteed accounts up to $250k. This meant that the government’s insurance program would ensure that everyone got the first $250,000 in their account returned in full.

The amounts above $250,000 were not insured. This is both a matter of law and a matter of paying for what you get. The FDIC charges a fee on the first $250,000 in an account based on the size and strength of the bank. This fee ranges from 0.015 percent to 0.40 percent annually, depending on the size and riskiness of the bank. Most people would not see the insurance fee directly, because it is charged to bank, but we can be sure that the bank passes this cost on to its depositors.

However, these fees only apply to the first $250,000 in an account. This means that people who had more than $250,000 in an account were not paying for insurance. Nonetheless, when they needed insurance from the government, they got it, even though they didn’t pay for it.

As we are now hearing, in many cases this handout ran into the tens of millions, or even billions, of dollars, almost all of it going to the very richest people in the country. Compare these depositors’ sense of entitlement to a government handout, to the outrage over President Biden’s proposal to forgive $10,000 of student loan debt. (To be clear, depositors likely would have gotten 80 to 90 percent of their money back in any case.)

In the case of SVB, rich depositors could not bother themselves with taking steps to ensure that their money was parked in a safe place. This is in spite of the fact that almost all of them pay people to help them manage their money.

By contrast, in the case of student loan debt, many 18-year-olds may have misjudged their future labor market prospects. This sort of error would not be surprising given the economic turmoil we have seen since the collapse of the housing bubble and the Great Recession.

Making the Rich Richer with Drugs and Vaccines

The idea that the purpose of government is to make the rich richer pervades every aspect of economic policy. When we were confronted with a worldwide pandemic, the government spent billions of dollars to quickly develop effective vaccines and treatments. And then, after developing them, we gave private companies like Moderna intellectual property rights over the product.

Naturally, this sent Moderna’s stock soaring and made at least five Moderna executives into billionaires. Only children and elite intellectuals could think the extreme inequality we see in this story has anything to do with the market, but we will get the same tale again and again. The right wants to accept market outcomes, while the left wants to use the government to address inequality.

It’s striking that even now the government is acting to make the Moderna crew still richer. Moderna and Pfizer have announced that they want to charge between $110 and $130 a shot for their new Covid booster.

Peter Hotez and Elena Bottazzi, two highly respected researchers at Baylor University and Texas Children’s Hospital, developed a simple to produce, 100 percent open-source Covid vaccine. It uses well-established technologies that are not complicated (unlike mRNA). Their vaccine has been widely used in India and Indonesia, with over 100 million people getting the vaccine to date.

If we want to see the vaccine used here it would need to be approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA). In principle, the FDA could rely on the clinical trials used to gain approval in India, but it indicated that they want a U.S. trial. (In fairness, India’s trials are probably lower quality.)

However, the government could fund a trial of Hotez-Bottazzi vaccine (Corbevax) with pots of money left over from Operation Warp Speed, or alternatively from the budgets of National Institutes of Health or other agencies like Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority (BARDA). With tens of billions of dollars of government money going to support biomedical research each year, the ten million or so needed for a clinical trial of Corbevax would be a drop in the bucket.

The arithmetic on this is incredible. Shots of Corbevax cost less than $2 a piece in India. If it costs two and a half times as much in the U.S., that still puts it at $5 a shot. That implies savings of more than $100 a shot.

That means that if we get 100,000 people to take the Corbevax booster, rather than the Modern-Pfizer ones (Pfizer is planning to also charge over $100 for its booster), we’ve covered the cost of the trials. If we get 1 million to take Corbevax, we’ve covered the cost ten times over, and if 10 million people get the Corbevax booster, we will have saved one hundred times the cost of the clinical trial.

But for now, we are not going this route. Remember, the purpose of government is to make the rich richer.

This is a huge story in the pharmaceutical industry more generally. We will spend close to $550 billion this year on prescription drugs. These drugs would almost certainly cost less than $100 billion a year if they were sold in a free market without government-granted patent monopolies or related protections.

The differences of $450 billion is roughly half the size of the military budget and more than four times what we will spend on the Food Stamp program. It comes to more than $3,000 per household each year, and yes, it mostly goes to people at the top end of the income distribution.

We would have to replace the roughly $100 billion a year that the industry spends on research, but we would almost certainly come out way ahead in that story, as with the Hotez-Bottazzi vaccine.

In addition, by making drugs cheap, we will end the crisis that many people face in trying to come up with the money to pay for life-saving drugs. We would also eliminate the enormous incentive that patent-protected drug prices give drug companies to lie about the safety and effectiveness of their drugs.

Structuring Finance to Serve the Market, not the Rich

We don’t need to have a financial system that has periodic bank collapses and makes millionaires and billionaires out of top bank executives. This is a policy choice by a government committed to making the rich richer.

The most obvious solution would be to have the Federal Reserve Board give every person and corporation in the country a digital bank account. The idea is that this would be a largely costless way for people to carry on their normal transactions. They could have their paychecks deposited there every two weeks or month. They could have their mortgage or rent, electric bill, credit card bill, and other bills paid directly from their accounts.

This sort of system could be operated at minimal cost, with the overwhelming majority of transactions handled electronically, requiring no human intervention. There could be modest charge for overdrafts, that would be structured to cover the cost of actually dealing with the problem, not gouging people to make big profits.

Former Fed economist (now at Dartmouth), Andy Levin, has been etching the outlines of this sort of system for a number of years. The idea would be to effectively separate out the banking system we use for carrying on transactions from the system we use for saving and financing investment.

We would have the Fed run system to carry out the vast majority of normal financial transactions, replacing the banks that we use now. However, we would continue to have investment banks, like Goldman Sachs and Morgan Stanley, that would borrow on financial markets and lend money to businesses, as well as underwriting stock and bond issues. While investment banks still require regulation to prevent abuses, we don’t have to worry about their failure shutting down the financial system.

Not only would the shift to Fed banking radically reduce the risk the financial sector poses to the economy, it would also make it hugely more efficient. We waste tens of billions of dollars every year maintaining the structure of a financial system that technology has made obsolete.

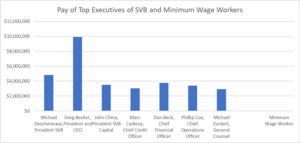

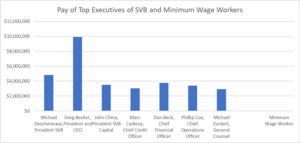

The current system also makes some people incredibly rich, even when they fail disastrously. Greg Becker, the President and Chief Executive Officer, earned $9,922,000 in SVB’s 2021 fiscal year (the most recent year for which I could find the data). That would be roughly 684 times what a minimum wage worker would earn for a full year’s work. (Top execs at the largest banks can earn three or four times this amount.)

If we think that a worker has a 45-year working lifetime, then Mr. Becker pulls down more in a year than what a minimum wage worker would get in 15 working lifetimes. The CEOs at Lehman and Bear Stearns, two of the huge failed banks in the financial crisis, walked away with hundreds of millions of dollars for their work.

So, the basic story is that the government has designed a financial system designed to redistribute massive amounts of money to the rich. We could have a hugely more efficient system, but since that would end the gravy train for those at the top, it is not on the political agenda.

The Big Lie: Conservatives Don’t Like Big Government

As this bailout should make clear is that, contrary to what the media tell us, conservatives love big government. They just think that the focus of big government should be making the rich as rich as possible, not helping ordinary people and securing the economy and society.

To be clear, I do think this bailout was necessary given the fragility of the economy at present (unlike the 2008-09 bailout, that was sold with the lie that we faced a Second Great Depression). However, we need to get our eye on the ball here.

The idea that conservatives like the market and not the government is unadulterated crap. It is a myth that they use to conceal the ways they have rigged the market to make income flow upward. Unfortunately, virtually the entire left has agreed to go along with this absurd myth. Moments like the bailout of the rich depositors at SVB make the truth about conservatives and the market apparent to all. (And yes, this is the point of Rigged [it’s free].)

There is a standard tale of politics where conservatives want to leave things to the market, whereas the left want a big role for government. The right likes to tell this story because it advantages them politically, since most people tend to have a positive view of the market. The left likes to tell it because they are not very good at politics and have an aversion to serious thinking.

The Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) bailout is yet another great example of how the right is just fine with government intervention, as long as the purpose is making the rich richer. Left to the market, the outcome in this case was clear. The FDIC guaranteed accounts up to $250k. This meant that the government’s insurance program would ensure that everyone got the first $250,000 in their account returned in full.

The amounts above $250,000 were not insured. This is both a matter of law and a matter of paying for what you get. The FDIC charges a fee on the first $250,000 in an account based on the size and strength of the bank. This fee ranges from 0.015 percent to 0.40 percent annually, depending on the size and riskiness of the bank. Most people would not see the insurance fee directly, because it is charged to bank, but we can be sure that the bank passes this cost on to its depositors.

However, these fees only apply to the first $250,000 in an account. This means that people who had more than $250,000 in an account were not paying for insurance. Nonetheless, when they needed insurance from the government, they got it, even though they didn’t pay for it.

As we are now hearing, in many cases this handout ran into the tens of millions, or even billions, of dollars, almost all of it going to the very richest people in the country. Compare these depositors’ sense of entitlement to a government handout, to the outrage over President Biden’s proposal to forgive $10,000 of student loan debt. (To be clear, depositors likely would have gotten 80 to 90 percent of their money back in any case.)

In the case of SVB, rich depositors could not bother themselves with taking steps to ensure that their money was parked in a safe place. This is in spite of the fact that almost all of them pay people to help them manage their money.

By contrast, in the case of student loan debt, many 18-year-olds may have misjudged their future labor market prospects. This sort of error would not be surprising given the economic turmoil we have seen since the collapse of the housing bubble and the Great Recession.

Making the Rich Richer with Drugs and Vaccines

The idea that the purpose of government is to make the rich richer pervades every aspect of economic policy. When we were confronted with a worldwide pandemic, the government spent billions of dollars to quickly develop effective vaccines and treatments. And then, after developing them, we gave private companies like Moderna intellectual property rights over the product.

Naturally, this sent Moderna’s stock soaring and made at least five Moderna executives into billionaires. Only children and elite intellectuals could think the extreme inequality we see in this story has anything to do with the market, but we will get the same tale again and again. The right wants to accept market outcomes, while the left wants to use the government to address inequality.

It’s striking that even now the government is acting to make the Moderna crew still richer. Moderna and Pfizer have announced that they want to charge between $110 and $130 a shot for their new Covid booster.

Peter Hotez and Elena Bottazzi, two highly respected researchers at Baylor University and Texas Children’s Hospital, developed a simple to produce, 100 percent open-source Covid vaccine. It uses well-established technologies that are not complicated (unlike mRNA). Their vaccine has been widely used in India and Indonesia, with over 100 million people getting the vaccine to date.

If we want to see the vaccine used here it would need to be approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA). In principle, the FDA could rely on the clinical trials used to gain approval in India, but it indicated that they want a U.S. trial. (In fairness, India’s trials are probably lower quality.)

However, the government could fund a trial of Hotez-Bottazzi vaccine (Corbevax) with pots of money left over from Operation Warp Speed, or alternatively from the budgets of National Institutes of Health or other agencies like Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority (BARDA). With tens of billions of dollars of government money going to support biomedical research each year, the ten million or so needed for a clinical trial of Corbevax would be a drop in the bucket.

The arithmetic on this is incredible. Shots of Corbevax cost less than $2 a piece in India. If it costs two and a half times as much in the U.S., that still puts it at $5 a shot. That implies savings of more than $100 a shot.

That means that if we get 100,000 people to take the Corbevax booster, rather than the Modern-Pfizer ones (Pfizer is planning to also charge over $100 for its booster), we’ve covered the cost of the trials. If we get 1 million to take Corbevax, we’ve covered the cost ten times over, and if 10 million people get the Corbevax booster, we will have saved one hundred times the cost of the clinical trial.

But for now, we are not going this route. Remember, the purpose of government is to make the rich richer.

This is a huge story in the pharmaceutical industry more generally. We will spend close to $550 billion this year on prescription drugs. These drugs would almost certainly cost less than $100 billion a year if they were sold in a free market without government-granted patent monopolies or related protections.

The differences of $450 billion is roughly half the size of the military budget and more than four times what we will spend on the Food Stamp program. It comes to more than $3,000 per household each year, and yes, it mostly goes to people at the top end of the income distribution.

We would have to replace the roughly $100 billion a year that the industry spends on research, but we would almost certainly come out way ahead in that story, as with the Hotez-Bottazzi vaccine.

In addition, by making drugs cheap, we will end the crisis that many people face in trying to come up with the money to pay for life-saving drugs. We would also eliminate the enormous incentive that patent-protected drug prices give drug companies to lie about the safety and effectiveness of their drugs.

Structuring Finance to Serve the Market, not the Rich

We don’t need to have a financial system that has periodic bank collapses and makes millionaires and billionaires out of top bank executives. This is a policy choice by a government committed to making the rich richer.

The most obvious solution would be to have the Federal Reserve Board give every person and corporation in the country a digital bank account. The idea is that this would be a largely costless way for people to carry on their normal transactions. They could have their paychecks deposited there every two weeks or month. They could have their mortgage or rent, electric bill, credit card bill, and other bills paid directly from their accounts.

This sort of system could be operated at minimal cost, with the overwhelming majority of transactions handled electronically, requiring no human intervention. There could be modest charge for overdrafts, that would be structured to cover the cost of actually dealing with the problem, not gouging people to make big profits.

Former Fed economist (now at Dartmouth), Andy Levin, has been etching the outlines of this sort of system for a number of years. The idea would be to effectively separate out the banking system we use for carrying on transactions from the system we use for saving and financing investment.

We would have the Fed run system to carry out the vast majority of normal financial transactions, replacing the banks that we use now. However, we would continue to have investment banks, like Goldman Sachs and Morgan Stanley, that would borrow on financial markets and lend money to businesses, as well as underwriting stock and bond issues. While investment banks still require regulation to prevent abuses, we don’t have to worry about their failure shutting down the financial system.

Not only would the shift to Fed banking radically reduce the risk the financial sector poses to the economy, it would also make it hugely more efficient. We waste tens of billions of dollars every year maintaining the structure of a financial system that technology has made obsolete.

The current system also makes some people incredibly rich, even when they fail disastrously. Greg Becker, the President and Chief Executive Officer, earned $9,922,000 in SVB’s 2021 fiscal year (the most recent year for which I could find the data). That would be roughly 684 times what a minimum wage worker would earn for a full year’s work. (Top execs at the largest banks can earn three or four times this amount.)

If we think that a worker has a 45-year working lifetime, then Mr. Becker pulls down more in a year than what a minimum wage worker would get in 15 working lifetimes. The CEOs at Lehman and Bear Stearns, two of the huge failed banks in the financial crisis, walked away with hundreds of millions of dollars for their work.

So, the basic story is that the government has designed a financial system designed to redistribute massive amounts of money to the rich. We could have a hugely more efficient system, but since that would end the gravy train for those at the top, it is not on the political agenda.

The Big Lie: Conservatives Don’t Like Big Government

As this bailout should make clear is that, contrary to what the media tell us, conservatives love big government. They just think that the focus of big government should be making the rich as rich as possible, not helping ordinary people and securing the economy and society.

To be clear, I do think this bailout was necessary given the fragility of the economy at present (unlike the 2008-09 bailout, that was sold with the lie that we faced a Second Great Depression). However, we need to get our eye on the ball here.

The idea that conservatives like the market and not the government is unadulterated crap. It is a myth that they use to conceal the ways they have rigged the market to make income flow upward. Unfortunately, virtually the entire left has agreed to go along with this absurd myth. Moments like the bailout of the rich depositors at SVB make the truth about conservatives and the market apparent to all. (And yes, this is the point of Rigged [it’s free].)

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The grant of copyright monopolies is a mechanism the government uses to support creative work. It is far from the only mechanism. The government funds creative work through agencies like the National Endowments for the Arts and Humanities, the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, and indirectly through its support of colleges and universities. It also provides support through the charitable contribution tax deduction, which subsidizes contributions that wealthy people choose to make to organizations that support creative work at the rate of almost 40 cents on the dollar.

The fact that copyright is just one of many tools for supporting creative work should be a central part of any discussion about ramping up in enforcement rules. Incredibly, this simple fact is altogether absent from a Washington Post column, by T Bone Burnett and Jonathan Taplin, arguing for the need for enhanced enforcement measures in the era of artificial intelligence (AI).

Copyright, AI and the Internet Age

Burnett and Taplin are concerned that AI programs will be able to freely surf the web, grabbing and recycling copyrighted material, without making any payments to the people who created the material. This is a very realistic concern.

As Burnett and Taplin point out, file sharing over the web has already cut sales of recorded music almost in half. (Actually, as a percent of GDP, the decline would be close to 70 percent.) The spread of AI programs is virtually certain to lead to even further declines in the future. Their response to this threat is to call for “new laws and regulations governing AI and safeguarding the human core of creative artistry.”

It’s important to realize that we already have created new laws and regulations to protect copyright in the Internet Age. Specifically, Congress passed the Digital Millennial Copyright Act (DMCA) in 1998 to establish rules for enforcing copyright on the Internet.

The DMCA requires website owners and Internet platforms to promptly remove infringing material after they have been notified by the person claiming infringement in order to protect themselves from an infringement suit. This threat is taken very seriously, since the law provides for statutory damages, and also legal fees.

This is a big deal. The actual damages resulting from most alleged acts of infringement would be trivial. Spotify compensates performing artists at an average rate of 0.4 cents per stream. That means that if the unauthorized posting of a copyrighted song allowed for 10,000 people to play the piece, the actual damages would be in the neighborhood of $40.

No one would pursue a lawsuit for such a small amount of money. However, the statutory damages allowed under the law can run into the thousands of dollars for even minor acts of infringement. In addition, a successful lawsuit can mean the defendant also has to pay several thousand dollars in legal fees.

As a result of these large potential damages, websites and platforms take removal notices very seriously. In fact, there is evidence that we see over-removal, with websites and platforms removing material where the notice may not properly represent someone with a legitimate copyright claim, or the material may reasonably qualify as “fair use.”

Whether or not we actually see over-removal, it is clear that copyright enforcement on the web imposes a substantial cost on society. Not only does it prevent direct acts of infringement, it also requires that third parties (the website or platform) police items that others post.

This cost is important to keep in mind when we consider Burnett and Taplin’s call for “new laws and regulations” to protect copyrighted material from AI. Almost by definition this means still larger costs for a mechanism that is providing relatively little revenue for creative workers.

An Alternative to Copyright

Rather than developing new laws and enforcement mechanisms to protect the relatively small revenue stream produced by copyright monopolies, we might look to alternative mechanisms for supporting creative work. We could go the route of increased funding for agencies like the National Endowments for the Art and Humanities, but this would raise political issues over who gets to decide what work is funded.

An alternative would be to build on the mechanism we already have in place with the charitable contribution tax deduction. As currently structured, this contribution benefits a small share of the population, since the vast majority of taxpayers take the standard deduction, which means they are not able to benefit from the charitable contribution tax deduction at all.

The deduction is also regressive, with higher income taxpayers effectively able to get a far larger subsidy for their contributions than middle income households. And of course, most of the contributions are not going for creative work.

But we could build on the basic logic of the charitable deduction where we give a public subsidy for individuals’ support of what very broadly are considered socially desirable ends. However, instead of making it a deduction, we could make it a refundable tax credit, and specify that the money go to support creative workers. (I outline this system in somewhat more detail in chapter 5 of Rigged [it’s free].)

On the first point, if some billionaire decides to give $100 million to their favorite church, the taxpayers are on the hook for $37 million of this payment, which is the reduction in their tax liability. Under a tax credit system, we would give every person the same amount, say $100 to $200, to contribute to whatever creative worker, or organization supporting creative workers, they want.

This would provide an enormous amount of money to support creative work. If we assume 70 percent of adults decide to use this free money, it would mean $17.5 billion to $35 billion a year, roughly 0.07 percent to 0.14 percent of GDP. The latter figure is more than twice as much as what is now paid for recorded music.

The condition for being eligible to get the money is that a creative worker or organization has to register with the I.R.S., or other designated agency, saying what it is they do. This is similar to what tax-exempt organizations must do now. They must say they are a church, a research organization, or charity providing food to the poor. The I.R.S. does not evaluate whether they are a good church or a good charity; its only obligation is to ensure that the organization is not committing fraud and is in fact what it claims.

In this case, a person would say they are a musician, singer, or some other type of creative worker (the law would have to specify how broadly this would be defined). If they are getting money as an organization, they would have to say that they support country music, mystery writers, or some other type of creative work. Just as is the case with tax-exempt organizations now, the government would not evaluate the quality of the work, just that the person or organization does what they claim.

There would also be another condition. If you get money through the tax credit system, you are not also eligible for copyright monopolies. The government gives you one subsidy, not two.

The neat part about this aspect of the system is that it is self-enforcing. There would be a public record of everyone getting money through the tax credit system. If any of these people subsequently tried to claim copyright infringement, their case would be immediately dismissed, since they were not eligible to get copyrights. This sort of subsidy would generate an enormous amount of material that could be freely distributed over the web, with no concerns about copyright.

It’s true that this system would lead to public support for work that people didn’t like. Virtually everyone would likely be able to identify something supported through the tax credit system that they found objectionable, and perhaps highly objectionable.

But this is also the case with the current system with the charitable deduction. Many of us find the activities of some organizations that get millions, or even billions, of tax subsidized dollars highly objectionable. We would have the same story here, but an organization that got a large amount of money would need to have a large number of people who supported it, not just a single billionaire.

There are issues that need to be addressed in constructing this sort of tax credit system. It can be sliced and diced in thousands of different ways. Should we make the dollar amount larger or smaller? Perhaps we should also allow a match, where if a person decides to contribute $100 of their own money, the government throws in another $100 or even $200.

We also have to decide which work qualifies. Presumably music and writing are obvious (how about journalism – seems very important), but what about movies or television shows? How about video games? I would argue for making the boundaries as large as plausible, which would presumably make a case for a larger credit, but this is the sort of thing that would need to be debated.

The key point is that we have options other than trying to revive a 500-year-old copyright system that is already on life support. Our creative workers may not be very creative when it comes to designing mechanisms to support their work, but the rest of us have to be.

The grant of copyright monopolies is a mechanism the government uses to support creative work. It is far from the only mechanism. The government funds creative work through agencies like the National Endowments for the Arts and Humanities, the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, and indirectly through its support of colleges and universities. It also provides support through the charitable contribution tax deduction, which subsidizes contributions that wealthy people choose to make to organizations that support creative work at the rate of almost 40 cents on the dollar.

The fact that copyright is just one of many tools for supporting creative work should be a central part of any discussion about ramping up in enforcement rules. Incredibly, this simple fact is altogether absent from a Washington Post column, by T Bone Burnett and Jonathan Taplin, arguing for the need for enhanced enforcement measures in the era of artificial intelligence (AI).

Copyright, AI and the Internet Age

Burnett and Taplin are concerned that AI programs will be able to freely surf the web, grabbing and recycling copyrighted material, without making any payments to the people who created the material. This is a very realistic concern.

As Burnett and Taplin point out, file sharing over the web has already cut sales of recorded music almost in half. (Actually, as a percent of GDP, the decline would be close to 70 percent.) The spread of AI programs is virtually certain to lead to even further declines in the future. Their response to this threat is to call for “new laws and regulations governing AI and safeguarding the human core of creative artistry.”

It’s important to realize that we already have created new laws and regulations to protect copyright in the Internet Age. Specifically, Congress passed the Digital Millennial Copyright Act (DMCA) in 1998 to establish rules for enforcing copyright on the Internet.

The DMCA requires website owners and Internet platforms to promptly remove infringing material after they have been notified by the person claiming infringement in order to protect themselves from an infringement suit. This threat is taken very seriously, since the law provides for statutory damages, and also legal fees.

This is a big deal. The actual damages resulting from most alleged acts of infringement would be trivial. Spotify compensates performing artists at an average rate of 0.4 cents per stream. That means that if the unauthorized posting of a copyrighted song allowed for 10,000 people to play the piece, the actual damages would be in the neighborhood of $40.

No one would pursue a lawsuit for such a small amount of money. However, the statutory damages allowed under the law can run into the thousands of dollars for even minor acts of infringement. In addition, a successful lawsuit can mean the defendant also has to pay several thousand dollars in legal fees.

As a result of these large potential damages, websites and platforms take removal notices very seriously. In fact, there is evidence that we see over-removal, with websites and platforms removing material where the notice may not properly represent someone with a legitimate copyright claim, or the material may reasonably qualify as “fair use.”

Whether or not we actually see over-removal, it is clear that copyright enforcement on the web imposes a substantial cost on society. Not only does it prevent direct acts of infringement, it also requires that third parties (the website or platform) police items that others post.

This cost is important to keep in mind when we consider Burnett and Taplin’s call for “new laws and regulations” to protect copyrighted material from AI. Almost by definition this means still larger costs for a mechanism that is providing relatively little revenue for creative workers.

An Alternative to Copyright

Rather than developing new laws and enforcement mechanisms to protect the relatively small revenue stream produced by copyright monopolies, we might look to alternative mechanisms for supporting creative work. We could go the route of increased funding for agencies like the National Endowments for the Art and Humanities, but this would raise political issues over who gets to decide what work is funded.

An alternative would be to build on the mechanism we already have in place with the charitable contribution tax deduction. As currently structured, this contribution benefits a small share of the population, since the vast majority of taxpayers take the standard deduction, which means they are not able to benefit from the charitable contribution tax deduction at all.

The deduction is also regressive, with higher income taxpayers effectively able to get a far larger subsidy for their contributions than middle income households. And of course, most of the contributions are not going for creative work.

But we could build on the basic logic of the charitable deduction where we give a public subsidy for individuals’ support of what very broadly are considered socially desirable ends. However, instead of making it a deduction, we could make it a refundable tax credit, and specify that the money go to support creative workers. (I outline this system in somewhat more detail in chapter 5 of Rigged [it’s free].)

On the first point, if some billionaire decides to give $100 million to their favorite church, the taxpayers are on the hook for $37 million of this payment, which is the reduction in their tax liability. Under a tax credit system, we would give every person the same amount, say $100 to $200, to contribute to whatever creative worker, or organization supporting creative workers, they want.

This would provide an enormous amount of money to support creative work. If we assume 70 percent of adults decide to use this free money, it would mean $17.5 billion to $35 billion a year, roughly 0.07 percent to 0.14 percent of GDP. The latter figure is more than twice as much as what is now paid for recorded music.

The condition for being eligible to get the money is that a creative worker or organization has to register with the I.R.S., or other designated agency, saying what it is they do. This is similar to what tax-exempt organizations must do now. They must say they are a church, a research organization, or charity providing food to the poor. The I.R.S. does not evaluate whether they are a good church or a good charity; its only obligation is to ensure that the organization is not committing fraud and is in fact what it claims.

In this case, a person would say they are a musician, singer, or some other type of creative worker (the law would have to specify how broadly this would be defined). If they are getting money as an organization, they would have to say that they support country music, mystery writers, or some other type of creative work. Just as is the case with tax-exempt organizations now, the government would not evaluate the quality of the work, just that the person or organization does what they claim.

There would also be another condition. If you get money through the tax credit system, you are not also eligible for copyright monopolies. The government gives you one subsidy, not two.

The neat part about this aspect of the system is that it is self-enforcing. There would be a public record of everyone getting money through the tax credit system. If any of these people subsequently tried to claim copyright infringement, their case would be immediately dismissed, since they were not eligible to get copyrights. This sort of subsidy would generate an enormous amount of material that could be freely distributed over the web, with no concerns about copyright.

It’s true that this system would lead to public support for work that people didn’t like. Virtually everyone would likely be able to identify something supported through the tax credit system that they found objectionable, and perhaps highly objectionable.

But this is also the case with the current system with the charitable deduction. Many of us find the activities of some organizations that get millions, or even billions, of tax subsidized dollars highly objectionable. We would have the same story here, but an organization that got a large amount of money would need to have a large number of people who supported it, not just a single billionaire.

There are issues that need to be addressed in constructing this sort of tax credit system. It can be sliced and diced in thousands of different ways. Should we make the dollar amount larger or smaller? Perhaps we should also allow a match, where if a person decides to contribute $100 of their own money, the government throws in another $100 or even $200.

We also have to decide which work qualifies. Presumably music and writing are obvious (how about journalism – seems very important), but what about movies or television shows? How about video games? I would argue for making the boundaries as large as plausible, which would presumably make a case for a larger credit, but this is the sort of thing that would need to be debated.

The key point is that we have options other than trying to revive a 500-year-old copyright system that is already on life support. Our creative workers may not be very creative when it comes to designing mechanisms to support their work, but the rest of us have to be.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

An item in Ezra Klein’s NYT column yesterday really grabbed by attention. Ezra cited a Wall Street Journal column that claimed that the Federal Reserve Board’s stress tests would not have detected Silicon Valley Bank’s (SVB) problems, because its stress tests did not consider interest rate risk.

This struck me as close to crazy. How could a stress test not consider interest rate risk? I recalled the stress tests that the Fed and Treasury performed very publicly in March of 2009, in the middle of the financial crisis. These tests did not consider interest rate risk for the simple reason that, at that point in time, soaring interest rates seemed about as likely as a Martian invasion.

I had not been following the Fed’s stress tests since that time, but I assumed that they did adjust them for circumstances. I recall back in 2002, when I first became concerned about the housing bubble, being on a radio show with the chief economist from Fannie Mae. He assured me that they could not have serious problems with a decline in housing prices, since they regularly stress test their assets. Their tests included a large rise in interest rates. (When the bubble finally burst, Fannie Mae, along with Freddie Mac, collapsed in the summer of 2008 and have been in conservatorship ever since.)

Anyhow, this exchange led me to believe that regulators applied some common sense to their stress test exercises and examined how bank assets would fare in all bad, but plausible, circumstances. In the years 2020-21, when 10-year Treasury rates were at times flirting with 1.0 percent, a sharp rise in interest rates had to be seen as a plausible, even if unlikely, possibility.

Incredibly, the Fed stress tests did not consider this scenario. This means that the Fed’s stress tests would not have detected the vulnerability of SVB to the sort of jump in interest rates that we have seen over the last year. That means that it is possible that, even if Dodd-Frank had not been weakened in 2018 to reduce the regulation to which SVB was subject, the Fed still would not have detected its problems.

I said “possible,” rather than asserting that the Fed would not have caught the bank’s vulnerabilities, because even without a stress test some items should have been apparent to anyone giving the bank careful scrutiny, as would have been required before the 2018 law weakening Dodd-Frank.

First and foremost, the bank had well over 90 percent of its liabilities in uninsured deposits. That has to be a red flag to any bank regulator. These are the deposits that are more likely to run in a crisis, since insured deposits have no reason to flee. Also, most banks have more of their liabilities in the form of bonds or other fixed term debt that cannot run.

The fact that the bank’s customers were highly concentrated in a single industry, the tech sector, also should have been a red flag. This is especially the case because tech has a long history as being a boom-bust industry.

Third, the bank’s assets had nearly tripled in size from the fourth quarter of 2019 to the fourth quarter of 2021. Again, any regulator with some clear eyes should have been asking if SVB was doing anything risky to bring about such extraordinary growth. As an old line goes, they should use their University of Chicago common sense: “If what we’re doing is not risky, why is the good lord being so nice to us?”

Anyhow, I mention these points since it still seems likely to me that if the Fed was applying the strict scrutiny to SVB, that had been required before the passage of the 2018 law weakening Dodd-Frank, it would have caught the bank’s vulnerabilities and required measures to shore up its capital and/or reduce its deposits. However, the stress tests the Fed was using would have been utterly worthless in detecting its problems.

This should be an important reminder that regulation does not necessarily solve market problems. Sometimes liberals seem to work from the assumption that if the market outcomes are getting things wrong, somehow bringing in the government will set things right.

This is often not the case. When I think back to my exchange with Fannie Mae’s chief economist, he insisted that a nationwide plunge in house prices was not even a possibility, since the country had never seen anything like that. While that was partly true (they did fall sharply in the Great Depression), we also had never seen the sort of nationwide run-up in house prices we were experiencing at the time.

But the key point was that he could not even consider the possibility that we were seeing a housing bubble, where house prices were being driven by irrational exuberance, rather than the fundamentals of the market. That was true of almost all the economists I encountered in those years. Even my friends largely did not buy the story, although they might politely nod when I made the case.

Anyhow, if we had more thoroughgoing regulation of the financial system in the years when the housing bubble was growing, there is little reason to think the regulators necessarily would have caught the financial system’s problems. After all, if the house price growth we saw in the bubble years made sense, then the banks’ behavior would not have been especially risky.

To my view, while we need government regulators in many circumstances, the most important part of the story is to structure the market to get the incentives right. That is why I have argued for a system where the Fed gives everyone an account which they can use for getting their paychecks, paying their bills, and other transactions.

This would be enormously more efficient than the current system, eliminating tens of billions in fees paid annually to the banks. The amount saved could be two or three times the price of Biden’s student loan debt forgiveness. It would also eliminate the problem of bankers sitting on huge pots of money where they can make great fortunes by taking big risks.

This is also the story with the pharmaceutical industry. If we paid for the development costs upfront, as we already do with more than $50 billion a year going to the National Institutes of Health, we would not only make drugs cheap (all drugs would be available as generics the day they are approved), we would also eliminate the incentive for drug companies to lie about their safety and effectiveness.

I have my longer tirade on this topic in chapter 5 of Rigged [it’s free], along with a discussion of other sectors. (See also here.) But the key point is that we can’t count on government regulation to right the wrongs of a badly structured market. Regulators can both make mistakes and also be corrupted by the industry they are regulating.

The most important reform is to structure the markets right in the first place, so that we can minimize the need for regulatory oversight. We need regulation in many circumstances, but even the best regulation will not correct the problems of a badly structured market.

An item in Ezra Klein’s NYT column yesterday really grabbed by attention. Ezra cited a Wall Street Journal column that claimed that the Federal Reserve Board’s stress tests would not have detected Silicon Valley Bank’s (SVB) problems, because its stress tests did not consider interest rate risk.

This struck me as close to crazy. How could a stress test not consider interest rate risk? I recalled the stress tests that the Fed and Treasury performed very publicly in March of 2009, in the middle of the financial crisis. These tests did not consider interest rate risk for the simple reason that, at that point in time, soaring interest rates seemed about as likely as a Martian invasion.

I had not been following the Fed’s stress tests since that time, but I assumed that they did adjust them for circumstances. I recall back in 2002, when I first became concerned about the housing bubble, being on a radio show with the chief economist from Fannie Mae. He assured me that they could not have serious problems with a decline in housing prices, since they regularly stress test their assets. Their tests included a large rise in interest rates. (When the bubble finally burst, Fannie Mae, along with Freddie Mac, collapsed in the summer of 2008 and have been in conservatorship ever since.)

Anyhow, this exchange led me to believe that regulators applied some common sense to their stress test exercises and examined how bank assets would fare in all bad, but plausible, circumstances. In the years 2020-21, when 10-year Treasury rates were at times flirting with 1.0 percent, a sharp rise in interest rates had to be seen as a plausible, even if unlikely, possibility.

Incredibly, the Fed stress tests did not consider this scenario. This means that the Fed’s stress tests would not have detected the vulnerability of SVB to the sort of jump in interest rates that we have seen over the last year. That means that it is possible that, even if Dodd-Frank had not been weakened in 2018 to reduce the regulation to which SVB was subject, the Fed still would not have detected its problems.

I said “possible,” rather than asserting that the Fed would not have caught the bank’s vulnerabilities, because even without a stress test some items should have been apparent to anyone giving the bank careful scrutiny, as would have been required before the 2018 law weakening Dodd-Frank.

First and foremost, the bank had well over 90 percent of its liabilities in uninsured deposits. That has to be a red flag to any bank regulator. These are the deposits that are more likely to run in a crisis, since insured deposits have no reason to flee. Also, most banks have more of their liabilities in the form of bonds or other fixed term debt that cannot run.

The fact that the bank’s customers were highly concentrated in a single industry, the tech sector, also should have been a red flag. This is especially the case because tech has a long history as being a boom-bust industry.

Third, the bank’s assets had nearly tripled in size from the fourth quarter of 2019 to the fourth quarter of 2021. Again, any regulator with some clear eyes should have been asking if SVB was doing anything risky to bring about such extraordinary growth. As an old line goes, they should use their University of Chicago common sense: “If what we’re doing is not risky, why is the good lord being so nice to us?”

Anyhow, I mention these points since it still seems likely to me that if the Fed was applying the strict scrutiny to SVB, that had been required before the passage of the 2018 law weakening Dodd-Frank, it would have caught the bank’s vulnerabilities and required measures to shore up its capital and/or reduce its deposits. However, the stress tests the Fed was using would have been utterly worthless in detecting its problems.

This should be an important reminder that regulation does not necessarily solve market problems. Sometimes liberals seem to work from the assumption that if the market outcomes are getting things wrong, somehow bringing in the government will set things right.

This is often not the case. When I think back to my exchange with Fannie Mae’s chief economist, he insisted that a nationwide plunge in house prices was not even a possibility, since the country had never seen anything like that. While that was partly true (they did fall sharply in the Great Depression), we also had never seen the sort of nationwide run-up in house prices we were experiencing at the time.

But the key point was that he could not even consider the possibility that we were seeing a housing bubble, where house prices were being driven by irrational exuberance, rather than the fundamentals of the market. That was true of almost all the economists I encountered in those years. Even my friends largely did not buy the story, although they might politely nod when I made the case.

Anyhow, if we had more thoroughgoing regulation of the financial system in the years when the housing bubble was growing, there is little reason to think the regulators necessarily would have caught the financial system’s problems. After all, if the house price growth we saw in the bubble years made sense, then the banks’ behavior would not have been especially risky.

To my view, while we need government regulators in many circumstances, the most important part of the story is to structure the market to get the incentives right. That is why I have argued for a system where the Fed gives everyone an account which they can use for getting their paychecks, paying their bills, and other transactions.

This would be enormously more efficient than the current system, eliminating tens of billions in fees paid annually to the banks. The amount saved could be two or three times the price of Biden’s student loan debt forgiveness. It would also eliminate the problem of bankers sitting on huge pots of money where they can make great fortunes by taking big risks.

This is also the story with the pharmaceutical industry. If we paid for the development costs upfront, as we already do with more than $50 billion a year going to the National Institutes of Health, we would not only make drugs cheap (all drugs would be available as generics the day they are approved), we would also eliminate the incentive for drug companies to lie about their safety and effectiveness.

I have my longer tirade on this topic in chapter 5 of Rigged [it’s free], along with a discussion of other sectors. (See also here.) But the key point is that we can’t count on government regulation to right the wrongs of a badly structured market. Regulators can both make mistakes and also be corrupted by the industry they are regulating.

The most important reform is to structure the markets right in the first place, so that we can minimize the need for regulatory oversight. We need regulation in many circumstances, but even the best regulation will not correct the problems of a badly structured market.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The New York Times seems to think it is a newspaper’s job to promote bank panics wherever possible. It would be difficult to explain its reporting on the Silicon Valley Bank’s (SVB) collapse any other way.

Last week it ran a piece implying that Silicon Valley’s tech sector was going to be seriously crippled by the collapse of the bank. The crippling would occur both, because they would lose a large chunk of their assets, which were in uninsured accounts at SVB, and also because they would lose access to a bank which was a major source of credit.

The first point was not plausibly true even at the time the NYT posted the story. When it seized the bank a week ago Friday, the FDIC issued a notice that it would give depositors an advance payment against the uninsured funds in their account the next week. It also said that it would give them a certificate for the remaining funds, the value of which would depend on how much it was able to collect by selling the bank’s assets.

The advance payment would almost certainly have been an amount equal to at least 50 percent of the uninsured deposits and quite possibly over 70 percent. The certificate would cover some fraction of the remaining amount.

While the depositors would have to wait for the FDIC to complete its resolution process to know how much they would ultimately get from their certificates, they would almost certainly be able to sell them to investors the day they were issued. This would likely mean a loss to these depositors, but we are almost certainly talking about less than 15 percent, and quite likely something close 5.0 percent. (The bonds of the bank were still selling for 30 cents on the dollar after the FDIC seizure was announced. No bond holder will collect a penny on their bonds, unless the depositors are paid in full.)

In short, the idea that Silicon Valley businesses would see their accounts zeroed out was always nonsense. Losing 5-15 percent of holdings above $250k would surely be a blow, but it is hard to believe this would devastate an otherwise thriving business.

On the second point, while other banks may not give quite the same service to Silicon Valley business people as SVB, banks are generally happy to make loans to thriving businesses. Also, part of the loss is personal to these people, not about their businesses.

“SVB’s home loans were significantly better than those from traditional banks, four people who received them said. The loans were $2.5 million to $6 million, with interest rates under 2.6 percent. Other banks had turned them down or, when given quotes for interest rates, offered over 3 percent, the people said.”

Anyhow, in a follow up today, the NYT gave us the timeline for Sara Mauskopf, a small business owner who had an account at SVB. The timeline goes over her experiences from first hearing about the bank’s troubles through the announcement on Sunday afternoon that everyone would have immediate access to the full amount in their accounts.

Incredibly, the piece never once mentions the FDIC’s statement when it took over the bank, that it would issue an advance payment within days and a certificate for the rest of the money. It is possible that Ms. Mauskopf did not know about this statement and the promise that most of the funds in her account would be available almost immediately.

If that is true, that would be a great story for a serious news outlet to pursue. Was Ms. Mauskopf typical among SVB depositors in not knowing that most of her account would be available to her the week after the bank had been seized?

If so, why were depositors not better informed about this fact? It could be because news outlets like the New York Times were more interested in promoting panic than in providing information, but that would just be speculation.

The New York Times seems to think it is a newspaper’s job to promote bank panics wherever possible. It would be difficult to explain its reporting on the Silicon Valley Bank’s (SVB) collapse any other way.

Last week it ran a piece implying that Silicon Valley’s tech sector was going to be seriously crippled by the collapse of the bank. The crippling would occur both, because they would lose a large chunk of their assets, which were in uninsured accounts at SVB, and also because they would lose access to a bank which was a major source of credit.

The first point was not plausibly true even at the time the NYT posted the story. When it seized the bank a week ago Friday, the FDIC issued a notice that it would give depositors an advance payment against the uninsured funds in their account the next week. It also said that it would give them a certificate for the remaining funds, the value of which would depend on how much it was able to collect by selling the bank’s assets.

The advance payment would almost certainly have been an amount equal to at least 50 percent of the uninsured deposits and quite possibly over 70 percent. The certificate would cover some fraction of the remaining amount.

While the depositors would have to wait for the FDIC to complete its resolution process to know how much they would ultimately get from their certificates, they would almost certainly be able to sell them to investors the day they were issued. This would likely mean a loss to these depositors, but we are almost certainly talking about less than 15 percent, and quite likely something close 5.0 percent. (The bonds of the bank were still selling for 30 cents on the dollar after the FDIC seizure was announced. No bond holder will collect a penny on their bonds, unless the depositors are paid in full.)

In short, the idea that Silicon Valley businesses would see their accounts zeroed out was always nonsense. Losing 5-15 percent of holdings above $250k would surely be a blow, but it is hard to believe this would devastate an otherwise thriving business.

On the second point, while other banks may not give quite the same service to Silicon Valley business people as SVB, banks are generally happy to make loans to thriving businesses. Also, part of the loss is personal to these people, not about their businesses.

“SVB’s home loans were significantly better than those from traditional banks, four people who received them said. The loans were $2.5 million to $6 million, with interest rates under 2.6 percent. Other banks had turned them down or, when given quotes for interest rates, offered over 3 percent, the people said.”

Anyhow, in a follow up today, the NYT gave us the timeline for Sara Mauskopf, a small business owner who had an account at SVB. The timeline goes over her experiences from first hearing about the bank’s troubles through the announcement on Sunday afternoon that everyone would have immediate access to the full amount in their accounts.

Incredibly, the piece never once mentions the FDIC’s statement when it took over the bank, that it would issue an advance payment within days and a certificate for the rest of the money. It is possible that Ms. Mauskopf did not know about this statement and the promise that most of the funds in her account would be available almost immediately.

If that is true, that would be a great story for a serious news outlet to pursue. Was Ms. Mauskopf typical among SVB depositors in not knowing that most of her account would be available to her the week after the bank had been seized?

If so, why were depositors not better informed about this fact? It could be because news outlets like the New York Times were more interested in promoting panic than in providing information, but that would just be speculation.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

David Wallace-Wells just wrote a column describing measures being passed in state legislatures controlled by Republicans, which will make it more difficult for governments to implement measures like temporary business closures or mask and vaccine mandates, all as tools to contain a deadly pandemic. While these laws may seem like an exercise in ungodly stupidity, the New York Times would not allow mention in its paper of restrictions that are likely to pose an even greater risk to public health in the next pandemic.

Of course, I am talking about intellectual property rules. Yes, I have been hitting this one hard in the last few days, but that is just because I find the arrogant ignorance on this issue so infuriating. And it matters.

We don’t know what the next deadly pandemic will look like, and with luck it will be many decades in the future. But we can envision what might have been different about the course of this pandemic if we went the open-source route, where all the science and technology was freely available for others to build on and to use to manufacture vaccines, tests, and treatments.

And, to be clear, this doesn’t mean that companies would not be compensated for their investments in developing the needed technology. The compensation would just take a different form, as a check from the government, rather than charging monopoly prices on vaccines or other products. Of course, companies could sue in court if they considered the compensation inadequate.

If we had gone down this route, all the information for making all vaccines, tests, and treatments would have been available for any manufacturer in the world. Governments interested in slowing the spread of the pandemic would also pay to produce and stockpile these products, especially vaccines, in advance of their approval by the FDA and other countries regulatory agencies.

This would be a very low risk proposition, since the vaccines were cheap to manufacture, less than $2 a shot in most cases. The potential loss from having to throw out 200 million vaccines that proved to be ineffective is trivial compared to the incredible benefits of having 200 million vaccines that could be quickly put into people’s arms once a vaccine was approved.

By pooling technology, we could ensure that people have a choice of vaccines. If people had refused to get vaccinated due to fears of mRNA vaccines (rational or otherwise), there were a number of vaccines based on well-established technologies that could have been made available as an alternative. (The FDA did approve non-mRNA vaccines manufactured by Johnson and Johnson and Novavax, but there were also non-mRNA vaccines widely used in other countries that in principle could have been available here.)

If a range of vaccines had been produced and stockpiled in vast quantities in 2020, when they were being tested for approval, we would have begun large-scale world-wide vaccination campaigns in late 2020 and the first months of 2021. This would have rapidly slowed the spread of the virus, almost certainly preventing the development of the omicron strain and quite possibly the delta strain.

That would have saved millions of lives and avoided trillions of dollars in economic damage. If we adopted the same approach to tests and treatments, this would both further reduce the spread and also the likelihood of death or serious illness among people who got infected.

But, any discussion of suspending intellectual property rules is strictly verboten in the New York Times. They only have space for trashing the Trumpers doing theatrics over banning pandemic mitigation measures. While these Trumpers do certainly deserve the criticism Wallace-Wells directs towards them, it would be great if we could have a discussion of the policies that do far more serious damage to public health, even if they mean big profits to the drug industry.

David Wallace-Wells just wrote a column describing measures being passed in state legislatures controlled by Republicans, which will make it more difficult for governments to implement measures like temporary business closures or mask and vaccine mandates, all as tools to contain a deadly pandemic. While these laws may seem like an exercise in ungodly stupidity, the New York Times would not allow mention in its paper of restrictions that are likely to pose an even greater risk to public health in the next pandemic.

Of course, I am talking about intellectual property rules. Yes, I have been hitting this one hard in the last few days, but that is just because I find the arrogant ignorance on this issue so infuriating. And it matters.

We don’t know what the next deadly pandemic will look like, and with luck it will be many decades in the future. But we can envision what might have been different about the course of this pandemic if we went the open-source route, where all the science and technology was freely available for others to build on and to use to manufacture vaccines, tests, and treatments.

And, to be clear, this doesn’t mean that companies would not be compensated for their investments in developing the needed technology. The compensation would just take a different form, as a check from the government, rather than charging monopoly prices on vaccines or other products. Of course, companies could sue in court if they considered the compensation inadequate.

If we had gone down this route, all the information for making all vaccines, tests, and treatments would have been available for any manufacturer in the world. Governments interested in slowing the spread of the pandemic would also pay to produce and stockpile these products, especially vaccines, in advance of their approval by the FDA and other countries regulatory agencies.

This would be a very low risk proposition, since the vaccines were cheap to manufacture, less than $2 a shot in most cases. The potential loss from having to throw out 200 million vaccines that proved to be ineffective is trivial compared to the incredible benefits of having 200 million vaccines that could be quickly put into people’s arms once a vaccine was approved.

By pooling technology, we could ensure that people have a choice of vaccines. If people had refused to get vaccinated due to fears of mRNA vaccines (rational or otherwise), there were a number of vaccines based on well-established technologies that could have been made available as an alternative. (The FDA did approve non-mRNA vaccines manufactured by Johnson and Johnson and Novavax, but there were also non-mRNA vaccines widely used in other countries that in principle could have been available here.)

If a range of vaccines had been produced and stockpiled in vast quantities in 2020, when they were being tested for approval, we would have begun large-scale world-wide vaccination campaigns in late 2020 and the first months of 2021. This would have rapidly slowed the spread of the virus, almost certainly preventing the development of the omicron strain and quite possibly the delta strain.

That would have saved millions of lives and avoided trillions of dollars in economic damage. If we adopted the same approach to tests and treatments, this would both further reduce the spread and also the likelihood of death or serious illness among people who got infected.

But, any discussion of suspending intellectual property rules is strictly verboten in the New York Times. They only have space for trashing the Trumpers doing theatrics over banning pandemic mitigation measures. While these Trumpers do certainly deserve the criticism Wallace-Wells directs towards them, it would be great if we could have a discussion of the policies that do far more serious damage to public health, even if they mean big profits to the drug industry.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

• Economic Crisis and RecoveryCrisis económica y recuperación

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

It really is bizarre how elite policy types have such a hard time thinking clearly about intellectual property. Earlier this week, I was beating up on the NYT for having two columns on preparing for the next pandemic, neither of which mentioned even once the issue of intellectual property.

This issue of intellectual property in a pandemic should not seem like an obscure topic. In the fall of 2020, India and South Africa proposed a resolution at the WTO that all intellectual property claims on vaccines, tests, and treatments be suspended for the duration of the pandemic.

More than 100 countries eventually signed on to the resolution. The United States and other wealthy countries subsequently filibustered the resolution to the point of irrelevance.

However, the idea that questions of intellectual property might be important in the next pandemic should not seem far-fetched. If we had eliminated all IP barriers (this would include both suspending patent monopolies and other forms of exclusivity, as well as not enforcing non-disclosure agreements), we quite likely could have had enough people around the world vaccinated quickly enough to have prevented the development of the Omicron strain of the coronavirus. It is even possible that we could have slowed the spread enough to prevent the Delta strain.

Imagine the millions of lives that could have been saved and the trillions of dollars of economic losses that would have been averted if these mutations had not developed. You might think this would be sufficient to interest the great minds that write about pandemics for the New York Times.

Just to be clear — suspending IP doesn’t mean that companies forego their profits from these claims. The idea is that the suspension would allow for the free flow of knowledge and technology to address the pandemic. After the fact, the companies would receive compensation from the government, and of course they would have every right to sue in court if they felt the compensation was inadequate. The point is that all effort should be focused on stopping the pandemic, and the money issues can be dealt with later.

Okay, it was pretty amazing to see this extraordinary neglect in the NYT, but Planet Money on NPR arguably went one better. It actually had a very interesting piece on drug costs and innovation, but then walked away from the big question it raised.

The piece pointed out that the United States pays more than any other country in the world because we grant drug companies patent monopolies and then let them charge whatever they want for their drugs. It then discussed President Biden’s plan to negotiate drug prices in Medicare, which the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) projected would save $25 billion a year.

It also noted that CBO projected that the reduction in drug company profits would result in a reduction of one percent in the number of drugs being developed. Since we develop roughly 45 new drugs a year, this would mean one less drug every two years. If that lost drug was an important treatment for cancer, diabetes, or some other serious illness, that would be a big loss.

But then the NPR piece cites another CBO study that calculates that we could offset the reduction in drug company research spending by increasing spending on NIH research by $1 billion. The piece then comments:

“So the policies together would save the government billions of dollars overall with minimal harm to innovation,” and then moves on.

Okay folks, let’s slow down and look at what NPR just told us. They said that $1 billion in government spending on research would offset the impact of a $25 billion reduction in drug prices. That is a 25 to 1 return on investment. In cost-benefit analyses, this would be off-the-charts crazy. A ratio of 1.1 is considered good, and 1.5 to 1 is great. If you can get to 2 to 1, that’s really fantastic. This is 25 to 1.

Maybe we should be asking if we can push this further and have the government pick up the whole tab for the research that is currently supported by patent monopolies (a bit over $100 billion a year at present), and let all new drugs be sold as cheap generics as soon as they are approved by the FDA. This could easily save us over $400 billion a year in spending on prescription drugs.

And, not only would drugs be cheap, we would also have removed the enormous incentive to be dishonest about the safety and effectiveness of drugs which results from patent monopoly pricing. We would also radically reduce the amount of money spent researching copycat drugs, and could instead direct more money into exploring cures and treatments that may not involve patentable products.

I wouldn’t necessarily expect this piece to go all the way down this road, but it is more than a bit incredible that they tell us that increased spending on NIH research can have a 2500 percent return on investment, and then just walk away from the issue. Is it not possible for people to think clearly about alternatives to patent monopolies for supporting the development of new drugs?

There is a lot of money, as well as peoples’ lives and health, at issue. It should be possible for our leading news outlets to think about the problem seriously and not let prejudices about intellectual property get in the way.

It really is bizarre how elite policy types have such a hard time thinking clearly about intellectual property. Earlier this week, I was beating up on the NYT for having two columns on preparing for the next pandemic, neither of which mentioned even once the issue of intellectual property.

This issue of intellectual property in a pandemic should not seem like an obscure topic. In the fall of 2020, India and South Africa proposed a resolution at the WTO that all intellectual property claims on vaccines, tests, and treatments be suspended for the duration of the pandemic.

More than 100 countries eventually signed on to the resolution. The United States and other wealthy countries subsequently filibustered the resolution to the point of irrelevance.

However, the idea that questions of intellectual property might be important in the next pandemic should not seem far-fetched. If we had eliminated all IP barriers (this would include both suspending patent monopolies and other forms of exclusivity, as well as not enforcing non-disclosure agreements), we quite likely could have had enough people around the world vaccinated quickly enough to have prevented the development of the Omicron strain of the coronavirus. It is even possible that we could have slowed the spread enough to prevent the Delta strain.

Imagine the millions of lives that could have been saved and the trillions of dollars of economic losses that would have been averted if these mutations had not developed. You might think this would be sufficient to interest the great minds that write about pandemics for the New York Times.

Just to be clear — suspending IP doesn’t mean that companies forego their profits from these claims. The idea is that the suspension would allow for the free flow of knowledge and technology to address the pandemic. After the fact, the companies would receive compensation from the government, and of course they would have every right to sue in court if they felt the compensation was inadequate. The point is that all effort should be focused on stopping the pandemic, and the money issues can be dealt with later.

Okay, it was pretty amazing to see this extraordinary neglect in the NYT, but Planet Money on NPR arguably went one better. It actually had a very interesting piece on drug costs and innovation, but then walked away from the big question it raised.

The piece pointed out that the United States pays more than any other country in the world because we grant drug companies patent monopolies and then let them charge whatever they want for their drugs. It then discussed President Biden’s plan to negotiate drug prices in Medicare, which the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) projected would save $25 billion a year.

It also noted that CBO projected that the reduction in drug company profits would result in a reduction of one percent in the number of drugs being developed. Since we develop roughly 45 new drugs a year, this would mean one less drug every two years. If that lost drug was an important treatment for cancer, diabetes, or some other serious illness, that would be a big loss.

But then the NPR piece cites another CBO study that calculates that we could offset the reduction in drug company research spending by increasing spending on NIH research by $1 billion. The piece then comments:

“So the policies together would save the government billions of dollars overall with minimal harm to innovation,” and then moves on.