• DebtEconomic Crisis and RecoveryCrisis económica y recuperaciónUnited StatesEE. UU.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

• COVID-19CoronavirusEconomic Crisis and RecoveryCrisis económica y recuperaciónInflationUnited StatesEE. UU.WagesWorkersSector del trabajo

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

• HousingInequalityLa DesigualdadUnited StatesEE. UU.

It is getting almost as bad as propaganda from an authoritarian regime. We keep hearing major news outlets tell us that inflation is whacking lower-income families. The Washington Post did it yesterday in an editorial demanding more rate hikes from the Fed to throw people out of work.

Lower-income people, like everyone else, are paying more for food, gas, and rent. The argument is that these items are a larger share of the budget of lower-income people, so they are hit harder by inflation than higher-income households.

The problem with telling this simple story is that wages have been growing most rapidly at the bottom end of the wage distribution, substantially outpacing inflation since the start of the pandemic. Also, in a tight labor market, more people are likely working in many households. They are also more likely to be able to find a job that has lower commuting costs or might allow them to work part-time to deal with child care or family needs.

One way to assess how these things balance out is to look at what has happened to homeownership rates. More homeownership is not always better, as some of us warned during the housing bubble years, but people who have the option to buy a home generally choose to do so.

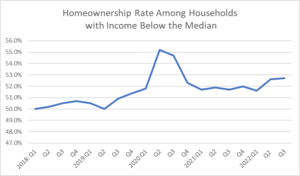

Contrary to the propaganda coming from the media, homeownership rates have actually risen rapidly since the pandemic for households with incomes below the median, as shown below. (The big jump in 2020, which was partially reversed, is likely due to a skewing in responses, as the pandemic sent response rates plummeting.)

Source: Census Bureau (Table 8).

Homeownership rates have also risen for Black and Hispanic households and those headed by someone under age 35. It is more than a bit bizarre that the media have been almost uniformly insisting that these are horrible times for lower-income people despite data that say the opposite.

It is getting almost as bad as propaganda from an authoritarian regime. We keep hearing major news outlets tell us that inflation is whacking lower-income families. The Washington Post did it yesterday in an editorial demanding more rate hikes from the Fed to throw people out of work.

Lower-income people, like everyone else, are paying more for food, gas, and rent. The argument is that these items are a larger share of the budget of lower-income people, so they are hit harder by inflation than higher-income households.

The problem with telling this simple story is that wages have been growing most rapidly at the bottom end of the wage distribution, substantially outpacing inflation since the start of the pandemic. Also, in a tight labor market, more people are likely working in many households. They are also more likely to be able to find a job that has lower commuting costs or might allow them to work part-time to deal with child care or family needs.

One way to assess how these things balance out is to look at what has happened to homeownership rates. More homeownership is not always better, as some of us warned during the housing bubble years, but people who have the option to buy a home generally choose to do so.

Contrary to the propaganda coming from the media, homeownership rates have actually risen rapidly since the pandemic for households with incomes below the median, as shown below. (The big jump in 2020, which was partially reversed, is likely due to a skewing in responses, as the pandemic sent response rates plummeting.)

Source: Census Bureau (Table 8).

Homeownership rates have also risen for Black and Hispanic households and those headed by someone under age 35. It is more than a bit bizarre that the media have been almost uniformly insisting that these are horrible times for lower-income people despite data that say the opposite.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

It’s more than a bit bizarre that until Elon Musk bought Twitter, most policy types apparently did not see a risk that huge platforms like Facebook and Twitter could be controlled by people with a clear political agenda. While just about everyone had some complaints about the moderation of these and other commonly used platforms, they clearly were not pushing Fox News-style nonsense.

With Elon Musk in charge, that may no longer be true. Musk has indicated his fondness for racists and anti-Semites, and made it clear that they are welcome on his new toy. He also is apparently good with right-wing kooks making up stories about everything from Paul Pelosi to Covid vaccines. (Remember, with Section 230 protection, Musk cannot be sued for defaming individuals and companies by mass-marketing lies, only the originators face any legal liability.)

If the hate and lies aren’t enough to make Twitter unattractive to the reality-based community, the right-wing crazies are putting together their lists of people to be purged. We don’t know who they will come up with, and what qualifies in their mind for banishment. We also don’t know whether the self-proclaimed free-speech absolutist Elon Musk will go along, but there certainly is a risk that Musk will want to keep his friends happy.

In that case, Twitter may go the way of Truth Social and Parlor, which would be unfortunate, but probably better than having a massive social media platform subject to Elon Musk’s whims. But we should still be asking how we can get in a situation where one right-wing jerk can have so much power?

The Problem of Media Concentration Is Not New

The Musk problem is hardly new. After all, Rupert Murdoch has been broadcasting his imaginary world to the country for decades, highlighting pressing national issues like the War on Christmas and President Obama’s tan suit.

But the problem goes well beyond Murdoch. Media outlets are owned and controlled by rich people and/or large corporations. They exist first and foremost to make money. While there are some cases where owners may genuinely have a commitment to using their news outlet to serve the public, for example, the Sulzberger family, which has controlled the New York Times for more than a century, these are the exceptions.

And, even with the exceptions, their perception of the public good is an extremely wealthy person’s perception of the public good. That may not be the same as the perception of an average working person struggling to get by.

As far as for-profit enterprises, news outlets have to be concerned about getting advertising. That may make them less likely to report news that will reflect poorly on major advertisers. That means things like both siding the role of the fossil fuel industry in global warming, or downplaying the windfall that corporations got from Trump’s 2017 tax cut.

This ownership structure could reasonably cause us to question the neutrality of news from outlets like CNN (owned by AT&T), ABC (owned by Disney), or NBC (owned by GE). But Musk’s takeover of Twitter takes the problem a step further. The viewership of each of the networks’ news shows numbers in the single digit millions. Twitter has almost 80 million active users in the United States. This means it matters much more if Twitter is taken over by a right-wing jerk than your average television network.

Alternatives to Corporate Control

Even though the media are incredibly important in shaping people’s view of the world, there has been remarkably little attention to the issue from most liberals or progressives. There are some small, and poorly funded, organizations, like Fairness and Accuracy in Reporting and Media Matters, which do focus on the issue. And there are a few prominent intellectuals who have written on the topic, like Rick McChesney, Dan Froomkin, and Jay Rosen, but for the most part, the issue of media control gets little attention from the left of center.

Ironically, campaign finance reform, which is almost certainly an exercise in futility given recent Supreme Court rulings, gets far more attention. The absurdity of the focus on campaign finance reform should be apparent to anyone who gives the issue a moment’s thought.

Suppose through some miracle Congress passed, and the Supreme Court upheld, a bill that limited billionaires’ abilities to buy political ads for their favorite candidate. Is anything going to stop these billionaires from buying up newspapers and television stations and running the ads supporting their favored candidates as news stories?

There is no remotely satisfying answer to that question, and it is ridiculous that campaign finance reformers haven’t recognized this fact. Limiting campaign spending by rich people will do nothing if we don’t do something to limit their ability to influence public opinion through the media.

Fortunately, there are some ideas for challenging the control the rich have over the media. The basic story is that we are not going to be able to prevent the rich from buying and owning media outlets. Instead, we will have to go the other way and allow the non-rich to have a voice.[1]

The idea is that we can give every person some amount of money (e.g. $100 to $200) to support the media outlet(s), or possibly a broader category of creative workers, of their choice. This system could be modeled along the lines of the charitable contribution tax deduction, where the government draws out general conditions for being eligible to receive the funds.

This means that the government specifies the types of organizations that can qualify to receive the funds. In the case of the charitable deduction, an organization has to indicate that it’s a church, it provides food for the poor, or does something else that qualifies it to be a charitable organization.

The government doesn’t try to determine whether it’s a good church or whether the food it provides is high quality, the only question is whether the organization does what it claims. A similar policy could be applied to the recipients of funds allocated through this system. (In my view, I would make not getting copyright protection a condition of getting funding – the government gives you one subsidy, not two – but that is the sort of issue that could be resolved down the road.)

This sort of system could provide a large amount of money to sustain media organizations that are not owned by rich people. For example, if the credit were $200, and 10 million people chose to support a specific television network with their full credit, the organization would have $2 billion a year to cover its operating expenses. That is roughly equal to CNN’s annual operating revenue.

This credit could create enormous opportunities for the non-rich to finance newspapers/websites, television stations, and other outlets that could compete with the current ones owned and controlled by billionaires. This path also has the great benefit that it could put adopted piecemeal, with states and even local governments, giving their residents the opportunity to support new types of news outlets.

If enough people could gain support for this type of program, they could get a more progressive state, like California or Massachusetts to pave the way, or a city like San Francisco or Seattle. Just as the movement for a higher minimum wage has spread from successes in these places, the same could happen with a tax credit system to support alternative media.

Fun with Elon Musk and Twitter

Even if it proves to be possible to advance a tax credit system to support alternatives to the billionaires’ media, we still have the problem of massive platforms like Facebook and Twitter being owned by rich people, who can essentially do what they want in accordance with their whims. The big problem here is the issue of network effects.

The idea of network effects is that people benefit from being part of a massive network since they want to be able to see what a large number of other people are posting, and they may hope that a large number of people will see what they post. These effects can be exaggerated. For example, the overwhelming majority of users will never have their Facebook pages or Twitter posts viewed by more than a small number of people. Nonetheless, they are real. This makes it hard to dislodge a Facebook or Twitter, once it has become dominant.

One route to go is to make the playing field less hospitable to large platforms. This can be done by removing Section 230 protections for websites that either sell advertising or personal information. This means that the big platforms could be held liable for defamatory material that they circulated over their platform.

In this scenario, if election deniers wrote posts on Twitter saying that Dominion voting machines had switched votes from Trump to Biden, Elon Musk could be sued by Dominion for defamation, just as Fox News is now being sued. The same would apply to the vaccine deniers claiming that Pfizer and Moderna vaccines have killed huge numbers of people.

Taking away Section 230 protection from these platforms would not just help large actors. As it stands now, if some racist asshole started posting on their Facebook page that a restaurant owned by Blacks or Asians had poisoned their family and sent them to the hospital, the restaurant owner would have no legal recourse against Facebook. They could sue the racist, who may not have much money, but they could not even force Facebook to take down the post.

By contrast, if a television station or newspaper had allowed the person to speak or printed a letter to the editor along the same lines, they would face liability. They could be forced to issue a correction to avoid being named in a defamation suit.

There are clearly complications with going this route. A platform with billions of posts daily could not be expected to monitor posts in advance for potentially defamatory material. This problem has been solved (imperfectly) with copyright, under the Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA), by requiring platforms to remove violating material in a timely manner after being notified by the copyright holder.

There could be a similar requirement for Internet sites. The evidence from the DMCA is that websites are overly cautious and err on the side of removing material even when the claim of violation is extremely weak. That may also prove to be the case with Internet platforms like Facebook and Twitter when it comes to allegedly defamatory material, but that is in part the point.

Part of the point of removing Section 230 protection from sites that rely on advertising or selling personal information is to put them at a disadvantage relative to sites that rely on subscriptions or donations to stay in business. In that case, people could count on posting material on a smaller site that might be removed by Facebook or Twitter. This would give sites operating on an alternative model a large advantage relative to the current Internet giants.

In any case, taking away Section 230 protection would clearly raise costs for the major Internet platforms. Given that Twitter was already struggling even before Elon Musk took it over, this sort of increase in costs would clearly be a serious blow.

Undoubtedly, changing the law on Section 230 protection would hurt some other sites as well. While some could probably switch over to a subscription model relatively easily, others may find it difficult. Sites will of course develop new modes of operation. For example, a site like Airbnb could require users to sign away their right to sue for defamation as a condition of usage.

As a practical matter, it is impossible to guarantee that there will be no negative outcomes from this change, just as is true of every policy that actually does anything in the world. The question is whether some number of sites either being seriously downsized, or going out of business altogether, is a price worth paying to prevent rich jerks from being able to operate huge platforms according to their whims.

To my view, it would be worth the price, but your mileage may vary. In any case, it is distressing to see we are now in a situation where this is the reality, not just a hypothetical one. It speaks volumes about the quality of intellectual debate in this country, that this possibility apparently caught so many of our leading policy types by surprise.

It’s more than a bit bizarre that until Elon Musk bought Twitter, most policy types apparently did not see a risk that huge platforms like Facebook and Twitter could be controlled by people with a clear political agenda. While just about everyone had some complaints about the moderation of these and other commonly used platforms, they clearly were not pushing Fox News-style nonsense.

With Elon Musk in charge, that may no longer be true. Musk has indicated his fondness for racists and anti-Semites, and made it clear that they are welcome on his new toy. He also is apparently good with right-wing kooks making up stories about everything from Paul Pelosi to Covid vaccines. (Remember, with Section 230 protection, Musk cannot be sued for defaming individuals and companies by mass-marketing lies, only the originators face any legal liability.)

If the hate and lies aren’t enough to make Twitter unattractive to the reality-based community, the right-wing crazies are putting together their lists of people to be purged. We don’t know who they will come up with, and what qualifies in their mind for banishment. We also don’t know whether the self-proclaimed free-speech absolutist Elon Musk will go along, but there certainly is a risk that Musk will want to keep his friends happy.

In that case, Twitter may go the way of Truth Social and Parlor, which would be unfortunate, but probably better than having a massive social media platform subject to Elon Musk’s whims. But we should still be asking how we can get in a situation where one right-wing jerk can have so much power?

The Problem of Media Concentration Is Not New

The Musk problem is hardly new. After all, Rupert Murdoch has been broadcasting his imaginary world to the country for decades, highlighting pressing national issues like the War on Christmas and President Obama’s tan suit.

But the problem goes well beyond Murdoch. Media outlets are owned and controlled by rich people and/or large corporations. They exist first and foremost to make money. While there are some cases where owners may genuinely have a commitment to using their news outlet to serve the public, for example, the Sulzberger family, which has controlled the New York Times for more than a century, these are the exceptions.

And, even with the exceptions, their perception of the public good is an extremely wealthy person’s perception of the public good. That may not be the same as the perception of an average working person struggling to get by.

As far as for-profit enterprises, news outlets have to be concerned about getting advertising. That may make them less likely to report news that will reflect poorly on major advertisers. That means things like both siding the role of the fossil fuel industry in global warming, or downplaying the windfall that corporations got from Trump’s 2017 tax cut.

This ownership structure could reasonably cause us to question the neutrality of news from outlets like CNN (owned by AT&T), ABC (owned by Disney), or NBC (owned by GE). But Musk’s takeover of Twitter takes the problem a step further. The viewership of each of the networks’ news shows numbers in the single digit millions. Twitter has almost 80 million active users in the United States. This means it matters much more if Twitter is taken over by a right-wing jerk than your average television network.

Alternatives to Corporate Control

Even though the media are incredibly important in shaping people’s view of the world, there has been remarkably little attention to the issue from most liberals or progressives. There are some small, and poorly funded, organizations, like Fairness and Accuracy in Reporting and Media Matters, which do focus on the issue. And there are a few prominent intellectuals who have written on the topic, like Rick McChesney, Dan Froomkin, and Jay Rosen, but for the most part, the issue of media control gets little attention from the left of center.

Ironically, campaign finance reform, which is almost certainly an exercise in futility given recent Supreme Court rulings, gets far more attention. The absurdity of the focus on campaign finance reform should be apparent to anyone who gives the issue a moment’s thought.

Suppose through some miracle Congress passed, and the Supreme Court upheld, a bill that limited billionaires’ abilities to buy political ads for their favorite candidate. Is anything going to stop these billionaires from buying up newspapers and television stations and running the ads supporting their favored candidates as news stories?

There is no remotely satisfying answer to that question, and it is ridiculous that campaign finance reformers haven’t recognized this fact. Limiting campaign spending by rich people will do nothing if we don’t do something to limit their ability to influence public opinion through the media.

Fortunately, there are some ideas for challenging the control the rich have over the media. The basic story is that we are not going to be able to prevent the rich from buying and owning media outlets. Instead, we will have to go the other way and allow the non-rich to have a voice.[1]

The idea is that we can give every person some amount of money (e.g. $100 to $200) to support the media outlet(s), or possibly a broader category of creative workers, of their choice. This system could be modeled along the lines of the charitable contribution tax deduction, where the government draws out general conditions for being eligible to receive the funds.

This means that the government specifies the types of organizations that can qualify to receive the funds. In the case of the charitable deduction, an organization has to indicate that it’s a church, it provides food for the poor, or does something else that qualifies it to be a charitable organization.

The government doesn’t try to determine whether it’s a good church or whether the food it provides is high quality, the only question is whether the organization does what it claims. A similar policy could be applied to the recipients of funds allocated through this system. (In my view, I would make not getting copyright protection a condition of getting funding – the government gives you one subsidy, not two – but that is the sort of issue that could be resolved down the road.)

This sort of system could provide a large amount of money to sustain media organizations that are not owned by rich people. For example, if the credit were $200, and 10 million people chose to support a specific television network with their full credit, the organization would have $2 billion a year to cover its operating expenses. That is roughly equal to CNN’s annual operating revenue.

This credit could create enormous opportunities for the non-rich to finance newspapers/websites, television stations, and other outlets that could compete with the current ones owned and controlled by billionaires. This path also has the great benefit that it could put adopted piecemeal, with states and even local governments, giving their residents the opportunity to support new types of news outlets.

If enough people could gain support for this type of program, they could get a more progressive state, like California or Massachusetts to pave the way, or a city like San Francisco or Seattle. Just as the movement for a higher minimum wage has spread from successes in these places, the same could happen with a tax credit system to support alternative media.

Fun with Elon Musk and Twitter

Even if it proves to be possible to advance a tax credit system to support alternatives to the billionaires’ media, we still have the problem of massive platforms like Facebook and Twitter being owned by rich people, who can essentially do what they want in accordance with their whims. The big problem here is the issue of network effects.

The idea of network effects is that people benefit from being part of a massive network since they want to be able to see what a large number of other people are posting, and they may hope that a large number of people will see what they post. These effects can be exaggerated. For example, the overwhelming majority of users will never have their Facebook pages or Twitter posts viewed by more than a small number of people. Nonetheless, they are real. This makes it hard to dislodge a Facebook or Twitter, once it has become dominant.

One route to go is to make the playing field less hospitable to large platforms. This can be done by removing Section 230 protections for websites that either sell advertising or personal information. This means that the big platforms could be held liable for defamatory material that they circulated over their platform.

In this scenario, if election deniers wrote posts on Twitter saying that Dominion voting machines had switched votes from Trump to Biden, Elon Musk could be sued by Dominion for defamation, just as Fox News is now being sued. The same would apply to the vaccine deniers claiming that Pfizer and Moderna vaccines have killed huge numbers of people.

Taking away Section 230 protection from these platforms would not just help large actors. As it stands now, if some racist asshole started posting on their Facebook page that a restaurant owned by Blacks or Asians had poisoned their family and sent them to the hospital, the restaurant owner would have no legal recourse against Facebook. They could sue the racist, who may not have much money, but they could not even force Facebook to take down the post.

By contrast, if a television station or newspaper had allowed the person to speak or printed a letter to the editor along the same lines, they would face liability. They could be forced to issue a correction to avoid being named in a defamation suit.

There are clearly complications with going this route. A platform with billions of posts daily could not be expected to monitor posts in advance for potentially defamatory material. This problem has been solved (imperfectly) with copyright, under the Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA), by requiring platforms to remove violating material in a timely manner after being notified by the copyright holder.

There could be a similar requirement for Internet sites. The evidence from the DMCA is that websites are overly cautious and err on the side of removing material even when the claim of violation is extremely weak. That may also prove to be the case with Internet platforms like Facebook and Twitter when it comes to allegedly defamatory material, but that is in part the point.

Part of the point of removing Section 230 protection from sites that rely on advertising or selling personal information is to put them at a disadvantage relative to sites that rely on subscriptions or donations to stay in business. In that case, people could count on posting material on a smaller site that might be removed by Facebook or Twitter. This would give sites operating on an alternative model a large advantage relative to the current Internet giants.

In any case, taking away Section 230 protection would clearly raise costs for the major Internet platforms. Given that Twitter was already struggling even before Elon Musk took it over, this sort of increase in costs would clearly be a serious blow.

Undoubtedly, changing the law on Section 230 protection would hurt some other sites as well. While some could probably switch over to a subscription model relatively easily, others may find it difficult. Sites will of course develop new modes of operation. For example, a site like Airbnb could require users to sign away their right to sue for defamation as a condition of usage.

As a practical matter, it is impossible to guarantee that there will be no negative outcomes from this change, just as is true of every policy that actually does anything in the world. The question is whether some number of sites either being seriously downsized, or going out of business altogether, is a price worth paying to prevent rich jerks from being able to operate huge platforms according to their whims.

To my view, it would be worth the price, but your mileage may vary. In any case, it is distressing to see we are now in a situation where this is the reality, not just a hypothetical one. It speaks volumes about the quality of intellectual debate in this country, that this possibility apparently caught so many of our leading policy types by surprise.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

• CryptoGlobal FinanceUnited StatesEE. UU.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

• Economic Crisis and RecoveryCrisis económica y recuperaciónInflationUnited StatesEE. UU.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

• COVID-19CoronavirusCryptoIntellectual PropertyPropiedad IntelectualUnited StatesEE. UU.

The World Health Organization is in the early phases of putting together an international agreement for dealing with pandemics. The goal is to ensure both that the world is prepared to fend off future pandemics by developing effective vaccines, tests, and treatments; and that these products are widely accessible, including in low-income countries that don’t have large amounts of money available for public health expenditures.

While the drafting of the agreement is still in its early phases, the shape of the main conflicts is already clear. The public health advocates, who want to ensure widespread access to these products, are trying to limit the extent to which patent monopolies and other protections price them out of the reach of developing countries. On the other side, the pharmaceutical industry wants these protections to be as long and as strong as possible, in order to maximize their profits. As Pfizer and Moderna know well, pandemics can be great for business.

The shape of this battle is hardly new. We saw the same story not just in the Covid pandemic, but also in the AIDS pandemic in the 1990s, when millions of people needlessly died in Sub-Saharan Africa because the U.S. and European pharmaceutical industries tried to block the widespread distribution of AIDS drugs.

Although the battle lines are familiar, one disturbing feature is the continuing failure of those concerned about inequality to take part in this debate. In the United States, we have plenty of groups and individuals who will spend endless hours fighting over clauses in the tax code that may give a few hundred million dollars to the rich. This is generally a good fight, but it is hard to understand the lack of interest in the structuring of a pandemic treaty that could mean hundreds of billions of dollars going to the rich.

This is not fanciful speculation. After the U.S. government paid Moderna $450 million to develop its Covid vaccine, and then another $450 million for the Phase 3 clinical trials, it then let the company have intellectual property rights in the vaccine. The stock price then increased more than ten-fold, creating at least five Moderna billionaires.

The extent of government support for the Moderna vaccine is extraordinary, but the basic story of drug companies getting huge profits, and select employees getting very rich, as a result of government research and government-granted patent monopolies, is very much the norm. The United States will pay close to $525 billion for prescription drugs in 2022.[1] It would likely be paying less than $100 billion in a free market, without patent monopolies and other forms of protection. The difference of $425 billion is more than half the size of the defense budget, it comes to more than $3,000 per family. And, it makes a relatively small number of people very rich.

The issue of intellectual property claims in the context of a pandemic preparedness agreement will not directly overturn the whole structure of the pharmaceutical industry, but it is likely to involve a substantial chunk of money if a future pandemic is similar to the Covid pandemic. It also could establish an alternative path for financing drug development.

If there was an agreement that publicly funded research would be freely shared across countries, and that anyone with the manufacturing capabilities could produce the drugs, vaccines, and tests that were produced by the research, it could establish the feasibility of a clear alternative to patent monopoly financed research. This could become a model for drug development more generally, which would jeopardize the huge fortunes being generated in the pharmaceutical industry.

For this reason, there is potentially an enormous amount of money at stake, with large impacts on inequality, in how a pandemic preparedness agreement is structured. In short, there is plenty here that should warrant the interest of the individuals and organizations that focus on inequality; they should be paying attention.

Of course, this doesn’t take away from the fact that the main focus of a pandemic agreement should be on saving lives. But the delays in sharing technology in the Covid pandemic strongly suggest that the path of open source research and free market production will be best both from the standpoint of reducing inequality and saving lives.

The Crypto Meltdown: Just Tax Gambling

I’ve been following economic debates long enough to have seen lots of craziness. In the 1990s stock bubble, I heard PhD economists telling me that we could count on the stock market going up 10 percent a year, even when price-to-earnings ratios were already at record highs. In the 00s, we had financial experts saying that housing was a safe investment because, even if the price plummeted, you could always live in your home.

The crypto craze has both bubbles beat, as the price of absolutely nothing soared to incredible levels. Other than possibly facilitating illegal transactions (I’ve heard law enforcement experts claim that crypto can now be traced relatively easily), there is no remotely plausible use for crypto. In other words, its price is pure speculation. Bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies have no intrinsic value, therefore the price can very possibly fall to zero, once the promoters run out of suckers, or “the brave,” as Matt Damon calls them.

Anyhow, this one really should not be hard from a policy standpoint. Putting money in crypto is gambling, pure and simple. We don’t make it illegal for people to gamble. They can gamble in Las Vegas bet on sports events and elections, or play the lottery. We just tax gambling so the government can get a cut and we try to make sure that people understand what they are doing – that they are playing a game that is structured so that they will lose.

In this sense, taxing crypto trades seems like an ideal policy. It will be a way to both get tax revenue and also to inform people that they are gambling, not investing. It looks like we presently have around $2 trillion a year in crypto trades. If we tax each trade at a 1.0 percent rate (half paid by the buyer and half by the seller), that would raise $20 billion a year, or $200 billion over a ten-year budget window.

A tax of this size (still far lower than taxes on casino gambling or lotteries) would hugely reduce the volume of trading, so the government may end up collecting half this amount, or even less. But, by reducing the resources that are tied up in crypto trading, we will be freeing up resources for productive uses, even if the government is not collecting the money in taxes. Think of it as an anti-inflation policy.

The good part of this story is that there really is no downside. When we tax things like food or gas, we make it more difficult for people to buy items that they need to get by. But who cares if it is more expensive for people to speculate with crypto?

The folks who run the crypto exchanges will be unhappy, as well as the celebrities who might get fewer dollars for their ads, but these people can instead try to channel their energy into something that is productive. People make money pushing heroin also, but no one feels bad about reducing opportunities in the heroin industry.

There also is a side benefit from a tax on crypto. It may get people to think more clearly about the financial sector generally. We need a financial sector to carry through transactions and to allocate capital, but we have seen the size of the financial sector explode (relative to the economy) in the last half century. This hugely bloated financial sector is an enormous drain of resources from the economy and a major source of inequality.

A tax on crypto can be a step towards implementing financial transaction taxes more generally. A tax on trades of stocks, bonds, and other assets would have to be far lower since there would be an economic cost from eliminating these trades altogether. But we could have a tax of, say 0.1 percent on stock trades, which would just raise trading costs back to their 1990s levels. This would eliminate much short-term speculative trading and could raise close to $100 billion a year.

We are very far from having the political support for a broad financial transactions tax, but perhaps the FTX meltdown can create enough anger to build momentum for a tax on crypto trades. It certainly seems like it’s worth a try.

Can Progressives Learn to be Opportunists?

The pandemic preparedness treaty and the crypto collapse might seem pretty far removed, but both present opportunities to crack down on major sources of waste and inequality in the economy. The right has been very clever in finding ways to undermine progressive structures and sources of power.

For example, they managed to destroy traditionally defined benefit pensions by inserting an obscure provision in the tax code, which created 401(k) defined contribution retirement accounts. They hugely undermined manufacturing unions by pursuing fictitious “free-trade” agreements, which subjected manufacturing workers to international competition, while protecting high-end professionals and increasing protections for patent and copyright monopolies.

The pandemic agreement provides a great opportunity to weaken patent monopolies and related protections while increasing the prospect that billions of people in the developing world will be able to survive the next pandemic. The crypto meltdown provides a window through which people may see the enormous waste and corruption in the financial sector. It would be great if progressives could take advantage of these opportunities.

[1] This figure comes from the Bureau of Economic Analysis, National Income and Product Accounts, Table 2.4.5U Line 121. The calculation of the cost without patent monopolies can be found here.

The World Health Organization is in the early phases of putting together an international agreement for dealing with pandemics. The goal is to ensure both that the world is prepared to fend off future pandemics by developing effective vaccines, tests, and treatments; and that these products are widely accessible, including in low-income countries that don’t have large amounts of money available for public health expenditures.

While the drafting of the agreement is still in its early phases, the shape of the main conflicts is already clear. The public health advocates, who want to ensure widespread access to these products, are trying to limit the extent to which patent monopolies and other protections price them out of the reach of developing countries. On the other side, the pharmaceutical industry wants these protections to be as long and as strong as possible, in order to maximize their profits. As Pfizer and Moderna know well, pandemics can be great for business.

The shape of this battle is hardly new. We saw the same story not just in the Covid pandemic, but also in the AIDS pandemic in the 1990s, when millions of people needlessly died in Sub-Saharan Africa because the U.S. and European pharmaceutical industries tried to block the widespread distribution of AIDS drugs.

Although the battle lines are familiar, one disturbing feature is the continuing failure of those concerned about inequality to take part in this debate. In the United States, we have plenty of groups and individuals who will spend endless hours fighting over clauses in the tax code that may give a few hundred million dollars to the rich. This is generally a good fight, but it is hard to understand the lack of interest in the structuring of a pandemic treaty that could mean hundreds of billions of dollars going to the rich.

This is not fanciful speculation. After the U.S. government paid Moderna $450 million to develop its Covid vaccine, and then another $450 million for the Phase 3 clinical trials, it then let the company have intellectual property rights in the vaccine. The stock price then increased more than ten-fold, creating at least five Moderna billionaires.

The extent of government support for the Moderna vaccine is extraordinary, but the basic story of drug companies getting huge profits, and select employees getting very rich, as a result of government research and government-granted patent monopolies, is very much the norm. The United States will pay close to $525 billion for prescription drugs in 2022.[1] It would likely be paying less than $100 billion in a free market, without patent monopolies and other forms of protection. The difference of $425 billion is more than half the size of the defense budget, it comes to more than $3,000 per family. And, it makes a relatively small number of people very rich.

The issue of intellectual property claims in the context of a pandemic preparedness agreement will not directly overturn the whole structure of the pharmaceutical industry, but it is likely to involve a substantial chunk of money if a future pandemic is similar to the Covid pandemic. It also could establish an alternative path for financing drug development.

If there was an agreement that publicly funded research would be freely shared across countries, and that anyone with the manufacturing capabilities could produce the drugs, vaccines, and tests that were produced by the research, it could establish the feasibility of a clear alternative to patent monopoly financed research. This could become a model for drug development more generally, which would jeopardize the huge fortunes being generated in the pharmaceutical industry.

For this reason, there is potentially an enormous amount of money at stake, with large impacts on inequality, in how a pandemic preparedness agreement is structured. In short, there is plenty here that should warrant the interest of the individuals and organizations that focus on inequality; they should be paying attention.

Of course, this doesn’t take away from the fact that the main focus of a pandemic agreement should be on saving lives. But the delays in sharing technology in the Covid pandemic strongly suggest that the path of open source research and free market production will be best both from the standpoint of reducing inequality and saving lives.

The Crypto Meltdown: Just Tax Gambling

I’ve been following economic debates long enough to have seen lots of craziness. In the 1990s stock bubble, I heard PhD economists telling me that we could count on the stock market going up 10 percent a year, even when price-to-earnings ratios were already at record highs. In the 00s, we had financial experts saying that housing was a safe investment because, even if the price plummeted, you could always live in your home.

The crypto craze has both bubbles beat, as the price of absolutely nothing soared to incredible levels. Other than possibly facilitating illegal transactions (I’ve heard law enforcement experts claim that crypto can now be traced relatively easily), there is no remotely plausible use for crypto. In other words, its price is pure speculation. Bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies have no intrinsic value, therefore the price can very possibly fall to zero, once the promoters run out of suckers, or “the brave,” as Matt Damon calls them.

Anyhow, this one really should not be hard from a policy standpoint. Putting money in crypto is gambling, pure and simple. We don’t make it illegal for people to gamble. They can gamble in Las Vegas bet on sports events and elections, or play the lottery. We just tax gambling so the government can get a cut and we try to make sure that people understand what they are doing – that they are playing a game that is structured so that they will lose.

In this sense, taxing crypto trades seems like an ideal policy. It will be a way to both get tax revenue and also to inform people that they are gambling, not investing. It looks like we presently have around $2 trillion a year in crypto trades. If we tax each trade at a 1.0 percent rate (half paid by the buyer and half by the seller), that would raise $20 billion a year, or $200 billion over a ten-year budget window.

A tax of this size (still far lower than taxes on casino gambling or lotteries) would hugely reduce the volume of trading, so the government may end up collecting half this amount, or even less. But, by reducing the resources that are tied up in crypto trading, we will be freeing up resources for productive uses, even if the government is not collecting the money in taxes. Think of it as an anti-inflation policy.

The good part of this story is that there really is no downside. When we tax things like food or gas, we make it more difficult for people to buy items that they need to get by. But who cares if it is more expensive for people to speculate with crypto?

The folks who run the crypto exchanges will be unhappy, as well as the celebrities who might get fewer dollars for their ads, but these people can instead try to channel their energy into something that is productive. People make money pushing heroin also, but no one feels bad about reducing opportunities in the heroin industry.

There also is a side benefit from a tax on crypto. It may get people to think more clearly about the financial sector generally. We need a financial sector to carry through transactions and to allocate capital, but we have seen the size of the financial sector explode (relative to the economy) in the last half century. This hugely bloated financial sector is an enormous drain of resources from the economy and a major source of inequality.

A tax on crypto can be a step towards implementing financial transaction taxes more generally. A tax on trades of stocks, bonds, and other assets would have to be far lower since there would be an economic cost from eliminating these trades altogether. But we could have a tax of, say 0.1 percent on stock trades, which would just raise trading costs back to their 1990s levels. This would eliminate much short-term speculative trading and could raise close to $100 billion a year.

We are very far from having the political support for a broad financial transactions tax, but perhaps the FTX meltdown can create enough anger to build momentum for a tax on crypto trades. It certainly seems like it’s worth a try.

Can Progressives Learn to be Opportunists?

The pandemic preparedness treaty and the crypto collapse might seem pretty far removed, but both present opportunities to crack down on major sources of waste and inequality in the economy. The right has been very clever in finding ways to undermine progressive structures and sources of power.

For example, they managed to destroy traditionally defined benefit pensions by inserting an obscure provision in the tax code, which created 401(k) defined contribution retirement accounts. They hugely undermined manufacturing unions by pursuing fictitious “free-trade” agreements, which subjected manufacturing workers to international competition, while protecting high-end professionals and increasing protections for patent and copyright monopolies.

The pandemic agreement provides a great opportunity to weaken patent monopolies and related protections while increasing the prospect that billions of people in the developing world will be able to survive the next pandemic. The crypto meltdown provides a window through which people may see the enormous waste and corruption in the financial sector. It would be great if progressives could take advantage of these opportunities.

[1] This figure comes from the Bureau of Economic Analysis, National Income and Product Accounts, Table 2.4.5U Line 121. The calculation of the cost without patent monopolies can be found here.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

• EnergyEnvironmentEuropeEuropaMedia

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

• Economic Crisis and RecoveryCrisis económica y recuperaciónInflationUnited StatesEE. UU.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

• CryptoFinancial Transaction TaxUnited StatesEE. UU.Wall StreetEl Mundo Financiero

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión