October 07, 2014

Dean Baker

October 7, 2014, Real-World Economics Review

See article at original source.

Thomas Piketty has done a great deal to add to our understanding of the economy. His work with Emmanual Saez and various other co-authors has hugely expanded our knowledge of trends in inequality in the United States and many other wealthy countries.1 Capital in the Twenty-First Century is another major contribution, provided us a treasure trove of data on trends in wealth distribution in the United States, United Kingdom, France, and a smattering of other countries, in some cases going back more than three centuries. This new data will undoubtedly provide the basis for much further research on wealth.

While few can question that Piketty has expanded our knowledge of wealth accumulation in the past, it is his predictions about the future that have garnered the most attention. Piketty notes the rapid increase in the concentration of wealth over the last three decades and sees it as part of a more general pattern in capitalism. He sees the period from World War I to the end of the 1970s as an anomaly. He argues that the general pattern of capitalism is to produce inequality. Two World Wars and the Great Depression gave the world a temporary reprieve from this trend as inequality fell sharply everywhere, but Piketty argues that capitalism is now back on its normal course, which means that inequality will continue to expand in the decades ahead. The remedy proposed in his book is a worldwide wealth tax, a proposal that Piketty recognizes as being nearly impossible politically. (In fairness, Piketty has been very open to other progressive policy proposals in discussions since his book came out.)

Before addressing the center of Piketty’s argument, it is worth clarifying Piketty’s focus. Unlike Marx’s Capital, which explicitly focused on money invested for profit, Piketty lumps all forms of wealth together for his analysis. This means the focus of his attention is not just shares of stock or bonds issued by private companies, but also housing wealth and wealth held in the form of government bonds. This is at least a peculiar mix since the value of these assets has often moved in opposite directions. For example, wealth held in government bonds in the United States declined from 114.9 percent of GDP in 1945 to 36.3 percent in the quarter century following World War II. Meanwhile the value of corporate equity rose from 49.8 percent of GDP in 1945 to 79.2 percent of GDP in 1970.2

There is a similar story with housing wealth. Nationwide house prices just moved in step with inflation over the period from 1950 to 1996.3 It was only in the period of the housing bubble that they began to substantially outpace the overall rate of inflation. While they have fallen back from their bubble peaks, house prices in 2014 are still close to 20 percent above their long-term trend. This pattern is noteworthy because it is difficult to envision a theory that would apply to both corporate profits (presumably the main determinant of share prices) and also housing values.

Should we believe that in a period of high corporate profits that Congress could not possibly limit the tax deduction for mortgage interest or take some other measure that would lead to a large hit to house prices? Again, housing wealth and wealth in equity have diverged sharply before, so if we are to believe that they will move together in the future then Piketty is claiming that the future will be very different from the past. And, the course of house prices will have much to do with the pattern of future wealth distribution. At $22.8 trillion, the value of the nation’s residential housing stock was not much smaller in value at the end of the first quarter of 2014 than the $27.8 trillion value of outstanding equity of U.S. corporations.4

Future trends in corporate profits

If we assume for the moment that Piketty does not want to predict the future of house prices, nor the course of public debt, his claim about the growing concentration of wealth comes down to a claim about the value of corporate stock. His claim is a strong one. He argues that wealth will grow relative to GDP. This hinges on the claim that the rate of profit will remain constant even as the ratio of wealth to GDP rises.5 This means that profit will comprise a

growing share of income through time.

There are two paths of logic that could generate this result and Piketty has chosen both, even though they are in direct opposition to each other. The first path is the ne of neo-classical economics in which profit is the marginal physical product of capital. This is a technical relationship. The other path is one based on institutions and the distribution of power. In this story profit depends to a large extent on the ability of owners of capital to rig the rules in their favor. As Piketty comments the recent rise in the capital share of output is: “consistent not only with an elasticity of substitution greater than one but also with an increase in capital’s bargaining power vis-à-vis labor over the past few decades” (p 221).

Piketty sets the stage for the first course when he briefly discusses the Cambridge Capital controversy. He pronounces Cambridge, MA the winner, even though the leading figures on the U.S. side conceded their defeat (Samuelson, 1966). Contrary to the treatment in Piketty, this was not a battle between England and its former colony, nor was it an empty exercise in economic esoterics. The real question was whether it made sense to talk about capital in the aggregate as a physical concept apart from the economic context in which it exists. This is not problematic in a one good economy, but as the Cambridge, UK economists made clear, it is not possible to aggregate types of capital without already knowing the interest rate.

This matters for Piketty’s claim because the Cambridge U.K. side established that the standard neo-classical production function did not make sense even in theory. The notion of an aggregate production function is logically incoherent. In his “Essay on Positive Economics,” Milton Freidman famously argued that it was reasonable to use simplifying assumptions in analyzing the economy even if they do not closely match reality. His model was the study of gravity where he said physicists would assume a vacuum, even though a perfect vacuum does not exist in the world.

The outcome of the Cambridge capital controversy would be the equivalent of showing a vacuum does not even make sense as a theoretical concept. The aggregate production function is simply not useful as a tool for economic analysis.

This is important for Piketty’s argument because in the neo-classical strain of his argument, the basis for the increasing capital share is Piketty’s claim that the elasticity of substitution between labor and capital is greater than one. However if aggregate production functions are not a sensible concept, then it would not be possible to derive this conclusion from determining the technical rate of substitution between labor and capital. Instead we would have to look at institutional and political factors to find the determinants of profit rates.

As a practical matter this seems the only plausible path forward. It is difficult to see how the length of a drug company’s patent monopoly or Microsoft’s copyright monopoly could be determined by the physical tradeoffs between labor and capital in the production process. The same would hold true of other factors that play a large role in determining aggregate profits. The decision by the United States to have its health care system run largely by for-profit insurers rather than a government agency surely is not technically determined. Nor is the decision to rely largely on private financial companies to provide retirement income for middle class workers. Similarly, the point at which the Federal Reserve Board clamps down on growth to prevent unemployment from falling and wage pressure from building is not determined by the technical features of the production process.6

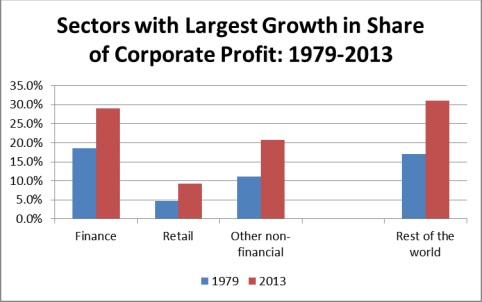

If we want to assess the whether it is likely that profits in the future will continue to rise as a share of output it is probably most useful to examine the recent trend in profits across sectors. Table 1 shows the sectors that have seen the largest rise in profit shares between 1979 and 2012, the most recent year for which industry level profit data are available.

Finance is the sector with the largest increase in profit shares, rising from an 18.4 percent share of domestic profits in 1979 to 29.1 percent share in 2013. Retail had a near doubling of its share from 4.7 percent in 1979 to a 9.3 percent share in 2013. This is presumably a Walmart effect as there was both some shift from wages to profits, but probably also a substantial reduction in the proprietorship share of retail, as chain stores replaced family run businesses. The category of “other non-financial” business includes a variety of industries, but it is likely that education and health care services account for much of the growth over this period. Finally, the last bar shows the growth in receipts of profits from the rest of the world (these are gross, not receipts).7 This increased 17.1 percent in 1979 to 31.1 percent in 2013. While some of this increase undoubtedly reflected the expansion of U.S. firms into other countries, it is likely that a substantial portion of this rise was simply an accounting maneuver for income tax purposes. It is a common practice to declare profits at subsidiaries located in low-tax countries, even if may not be plausible that the income in any real way originated in those subsidies.

If these sectors that drove the rise in profit shares are examined more closely, it is easy to envision policy changes that would reverse some or all of this increase. In the case of the financial sector, a policy that limited the size of financial firms coupled with taxes imposed on the financial sector that equalized taxation with other industries would likely take much of the profit out of the sector. The International Monetary Fund (2014) recently estimated the value of implicit too big to fail subsidies for large banks at $50 billion a year in the United States, almost 5 percent of after-tax corporate profits.8 To equalize tax burdens across industries the I.M.F. (2010) recommended a tax on the financial sector equal to roughly 0.2 percent of GDP ($35 billion in the U.S. economy in 2013). These policies alone would go far toward bringing the financial industry’s profits close to their 2010 share. Other policies that would further reduce its share would include simplifying the tax code to reduce the profits to be made by tax avoidance schemes and expansion of welfare state protections such as Social Security or public health care insurance that would reduce the need for services provided by the financial sector.

The soaring profits of the retail sector are in part attributable to the low wages in the sector. If wages rose through a combination of tighter labor markets, successful unionization measures, and higher minimum wage laws, it is likely that a substantial portion of the increase would be at the expense of corporate profits. Labor compensation in the retail sector in 2013 was roughly $530 billion.9 If this was increased by one-third due to the factors noted above, and one third of this increase was at the expense of profits in the sector, then profits in retail would fall by almost 30 percent, retreating most of the way back to their 1979 share.

While the “other” category would require a more detailed analysis than is possible with the published NIPA data, it is clear that the profits in the education and the health care sector depend largely on the government. If the government either reduced payments in these areas, or directly offered these services themselves, as is the case in most other countries, then the profits earned by the firms operating in these sectors would fall sharply.

Finally, there is the rapid growth in the foreign profit share. This also involves a variety of factors, but a substantial part of the picture is the use of foreign tax havens. This is especially important for industries that heavily rely on intellectual property like patents and copyrights, since it is a relatively simple matter to locate the holder of these claims anywhere in the world. Hence Apple can have a substantial portion of the profits from its iPhones or other devices show up in low-tax Ireland. In such cases the growth in foreign profits is actually growth in domestic profits attributable to intellectual property claims.

The existence and strength of intellectual property is of course very much a matter of government policy. And it is likely to have a large impact on profits. The United States spend $384 billion on pharmaceuticals in 2013.10 Without patents and related protections, it is likely that the cost would have been 10-20 percent as high. The difference of $307 billion to $346 billion is equal to 18.1 percent and 20.4 percent of before tax profits in 2013. While it is important for the government to have a mechanism to finance the research and development of new drugs, the patent system has become an extremely inefficient way to accomplish this end.11 More efficient alternatives to patent protection are likely to lead to considerably lower profits in the drug industry.

Similarly weaker patent protections in the tech sector, where it patent litigation has become a mechanism for harassing competitors, is likely to both enhance innovation and reduce profitability in the sector. The same would be the case for overly strict and long copyright monopolies held by the software and entertainment industry.

In short, profits in large sectors of the economy can be substantially reduced by policies that ould in many cases actually increase economic efficiency. In all cases industry groups would fight hard to prevent the basis of their profitability from being undermined, but that doesn’t change the fact that it is the adoption of policies that were friendly to these business interests that led to the increase in profit shares in recent years, not any inherent dynamic of capitalism, as some may read Piketty as saying.

Furthermore, even if these power relations are viewed as in some sense endogenous, there is still the obvious point that they can be changed – or least are more likely to be changed than a policy that attacked the whole capital class, like Piketty’s wealth tax. In other words, it seems more plausible that we can get legislation that would end patent support of prescription drug research, than an annual tax of 2.0 percent on wealth over some designated minimum. If the latter can be done without violent revolution, then surely the former can also be done. In short, it is difficult to accept Piketty’s projection of a future of growing inequality. This is certainly one possibility, but that is a prediction of the politics that will set policy in coming decades in the United States and elsewhere. It is not a statement about the fundamental nature of capitalism.

References

Baker, Dean and Jared Bernstein, 2014. Getting Back to Full Employment: A Better Bargain for Working People, Washington, DC: Center for Economic and Policy Research, accessed at https://www.cepr.net/index.php/publications/books/getting-back-to-full-employment-a-better-bargain-for-working-people

Baker, Dean, 2004. “Financing Drug Research: What Are the Issues?” Washington, DC: Center for Economic and Policy Research, accessed at https://www.cepr.net/index.php/Publications/Reports/financing-drug-research-what-are-the-issues

Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, 2014 Financial Accounts of the United States, Washington, DC: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, accessed at http://www.federalreserve.gov/releases/z1/

International Monetary Fund, 2014. “How Big is the Subsidy for Banks Considered Too Important to Fail,” in Global Financial Stability Report, Washington, DC: International Monetary Fund

International Monetary Fund, 2010. “A Fair and Substantial Contribution by the Financial Sector,” Final Report to the G-20, Washington, DC: International Monetary Fund.

Piketty, Thomas, 2014. Capital for the Twenty-First Century. New York: Belknap Press.

Samuelson, Paul A. 1966. “A Summing Up.” Quarterly Journal of Economics. November, 80:4, pp. 568–83.

U.S. Department of Commerce, Bureau of Economic Analysis, National Income and Product Accounts, accessed at http://www.bea.gov/iTable/index_nipa.cfm