December 07, 2016

This is the second blog post in a three-part series on the Affordable Care Act’s potential effects on part-time employment. The first and third posts can be read here and here.

In 2013, critics of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) rolled out a new complaint about the law: it would lead to a dramatic increase in involuntary part-time employment. Maria Bartiromo, Robert Samuelson, and Fox News all argued that firms would move workers from full-time to part-time status due to the law’s “employer mandate”. And while most critics have since shifted to other arguments against the ACA, Fox News has continued pushing this particular line.

To be clear, there is anecdotal evidence that at least some firms really are cutting back on their workers’ hours. So there has undoubtedly been at least some increase in involuntary part-time employment as a result of the mandate.

However, the discussion surrounding the employer mandate paints a rather incomplete picture of the ACA’s effect on involuntary part-time work, for two reasons. First, the discussion often lacks empirical evidence about the potential size of the mandate’s impact. To the extent that economic analysts have looked into this particular issue, they have generally found that the mandate caused little to no increase in involuntary part-time work, with even the largest purported increases being completely invisible in the aggregate national data.[1]

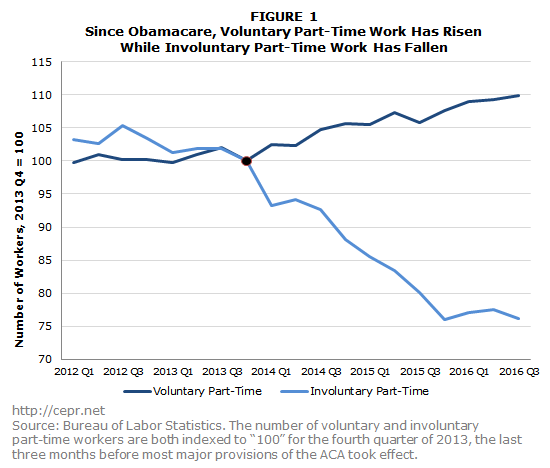

Second, the employer mandate is just one channel through which the ACA impacts involuntary part-time employment. While the mandate itself likely led to a (very) small increase in underemployment, there are at least two other aspects of the ACA which likely led to a decrease in involuntary part-time work. Moreover, there has been a rather marked drop in involuntary part-time employment since the ACA went into effect:

The first post in this series argued that the increase in voluntary part-time work depicted above may be attributable to the ACA. Moreover, as figure 1 shows, the periods with the largest increases in voluntary part-time employment also experienced large declines in involuntary part-time employment. For example, in the first quarter of 2014 – right when the ACA was first being implemented – voluntary part-time employment shot up 2.4 percent, the largest increase in over a decade. That same quarter, involuntary part-time employment fell by 6.8 percent, the greatest decrease since 2005. This raises the question of whether the ACA, by increasing voluntary part-time work, may actually have caused a decline in involuntary part-time employment. In other words, did reduced hours by some workers open up full-time positions for others?

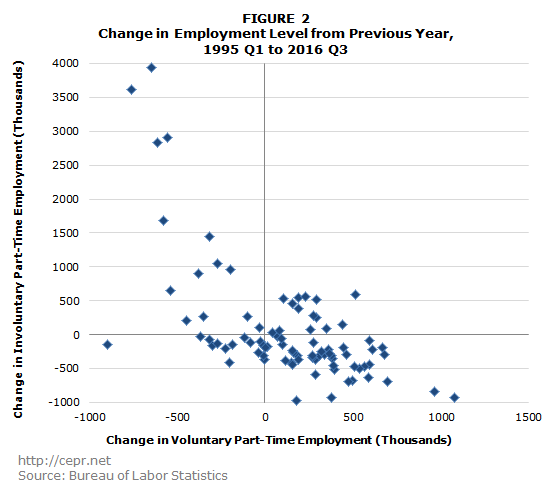

If this is the case, there should be a negative correlation in the historical data on voluntary and involuntary part-time employment. Figure 2 shows that this is indeed the case: increases in voluntary part-time employment have generally been associated with decreases in involuntary part-time employment. Insofar as Obamacare allowed some workers to cut back on their hours, it likely created more opportunities for involuntary part-time workers to move to full-time employment.

There is a third way that the ACA could affect the level of involuntary part-time employment: higher demand. At the end of 2013, there was significant cyclical weakness in the economy – and even today, there is evidence that the job market hasn’t fully recovered from the 2008 recession. According to the Congressional Budget Office, this means that the ACA could actually decrease involuntary part-time employment by providing a small amount of fiscal stimulus:

“[T]he ACA’s subsidies for health insurance will both stimulate demand for health care services and allow low-income households to redirect some of the funds that they would have spent on that care toward the purchase of other goods and services—thereby increasing overall demand. That increase in overall demand while the economy remains somewhat weak will induce some employers to hire more workers or to increase the hours of current employees during that period” (pg. 118).

“The expanded federal subsidies for health insurance will stimulate demand for goods and services, and that effect will mostly occur over the next few years. That increase in demand will induce some employers to hire more workers or to increase their employees’ hours during that period” (pg. 126).

In order to determine the ACA’s overall effect on involuntary part-time employment, we’d need precise estimates for the magnitudes of: 1) the increase in involuntary part-time work due to the employer mandate; 2) the decrease in involuntary part-time work stemming from the increase in voluntary part-time work; and 3) the decrease in involuntary part-time work thanks to the fiscal stimulus provided by the health insurance subsidies. It’s probably the case that the second and third factors outweigh the first, though we can’t be certain. What is certain, though, is that the projected increase in involuntary part-time employment never materialized. Relative to the fourth quarter of 2013, overall employment is up 5.2 percent; full-time employment is up 6.3 percent, and voluntary part-time employment is up 9.9 percent. By contrast, involuntary part-time employment is down 23.9 percent. If Obamacare was supposed to cause an increase in involuntary part-time work, the economy never got the message.

[1] This FiveThirtyEight analysis presented a different theory: even if Obamacare hasn’t caused an increase in involuntary part-time employment, it has led employers to cut back on the hours of workers who were already part-time. The piece noted that the share of part-time workers employed 31-34 hours per week fell in 2013 and 2014, while the share employed 25-29 hours went up. However, there are three big reasons to doubt this analysis. First, insofar as some employees shifted from working 31-34 hours per week to working 25-29 hours per week, there should’ve been a decrease in the average length of the workweek among the affected workers. However, the average workweek for involuntary part-time workers has increased slightly since Obamacare went into effect, while the average workweek for voluntary part-time workers has fallen. This means that the shift from working 31-34 hours to working 25-29 hours was more likely driven by workers choosing to work fewer hours rather than employers cutting back on workers’ hours. Second, the reported trend appears to have reversed itself since FiveThirtyEight published its analysis. In 2013, 12.2 percent of the workforce was employed 15-29 hours per week; in 2014, that figure rose to 12.4 percent. However, in 2015 – when the employer mandate actually took effect – just 11.9 percent of the workforce was employed 15-29 hours per week. Third, the look-back period that was the basis for the mandate was 2014. CEPR did an analysis of hours in the first half of 2013, which was a period when employers would have thought the mandate applied. The percent of the workforce employed 25-29 hours rose slightly, but this was at the expense of those working even fewer hours or people who reported that their hours varied. In July, the Obama administration announced that the mandate would not take effect in 2014, which meant that the hours worked in the second half of 2013 would not affect their liability for the penalty.