May 02, 2018

In 1991, Argentina fixed its peso to the US dollar, but the increasing value of the dollar led to a deep recession beginning in mid-1998, and default on dollar-denominated debt in December 2001. The currency board devalued the peso by 29 percent in January 2002, before the peso fell further over the year as the peg was abandoned completely.

The year 2001 also represented a low point in Argentina’s commodity prices. From 2001 to 2011, prices rose 187 percent — much faster than import prices generally, which rose 42 percent over the same period. This was the largest relative increase in commodity prices since 1933, shortly after Argentina abandoned the gold standard.

This has led some observers to attribute Argentina’s rapid economic growth after coming out of recession to a commodity boom, but an increase in commodity prices can cut both ways, increasing the price of purchases as well as sales. Indeed, there was considerable improvement in the terms of trade over 2001–2011, and the price of gross domestic product (GDP) relative to that of domestic demand (domestic consumption and investment) grew only about 7.5 percent. This suggests that the impact on real output was modest — perhaps less than 3 percent over the decade.

In a recent paper, Thomas Drechsel and Silvana Tenreyro study the economic effects of commodity price shocks. In part, they apply a vector autoregression (VAR) statistical model to data from Argentina going back to 1900. In brief, they find that an economy-wide shock[1] that immediately raises commodity prices by 9–11 percent temporarily increases real per-capita GDP 0.6–2.3 percentage points by the following year. They find through this approach no evidence that such a shock has any long-run effect.

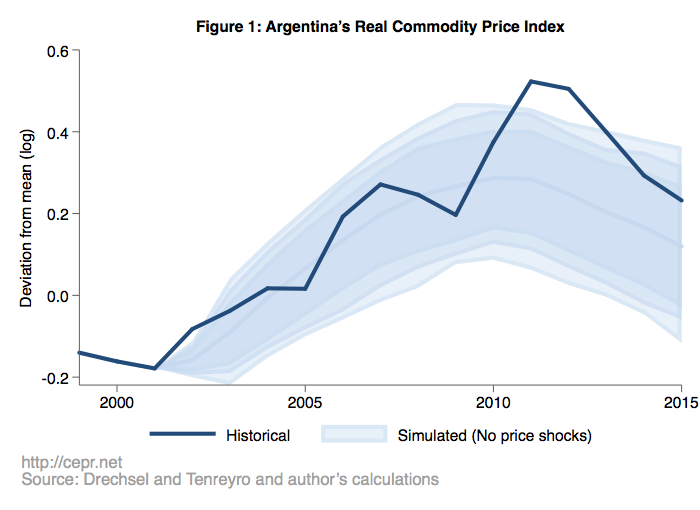

Though real commodity prices doubled between 2001 and 2011, Drechsel and Tenreyro’s VAR model suggests that for most of the decade commodity-price shocks do not contribute meaningfully to the evolution of commodity prices over the decade. Figure 1 below shows historical real commodity prices (dark blue) along with simulated results having removed the exogenous price shocks after 2001 (light bands span 80, 90, and 95 percent of simulations). Only after 2010 did exogenous price shocks drive prices above the expected range.

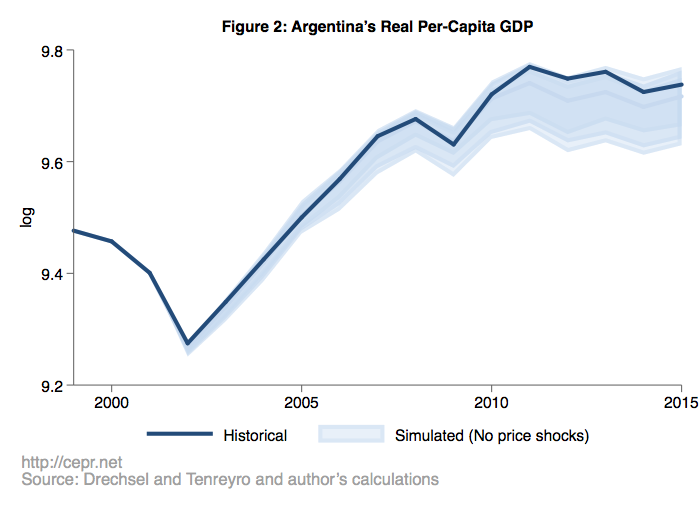

Consequently, the accumulated price shocks after 2001 only increased GDP 4 percent by 2012 — raising the annualized rate of per-capita growth over 11 years from 2.8 percent to 3.2 percent. Though it may be that commodity-price shocks contributed to growth in Argentina, we see little evidence that it drove the rapid economic growth of the 2000s. This is seen in Figure 2.

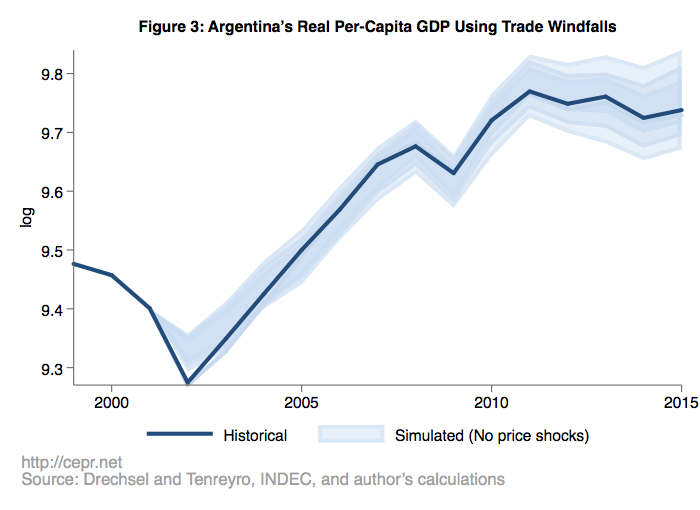

Finally, we may repeat the above analysis using our measure of trade windfalls — the price of GDP relative to that of domestic demand — in lieu of real commodity prices. As Figure 3 shows, the additional purchasing power that was made available through changes in trade prices had no observable effect on GDP.

[1] Unexpected movements in commodity prices are correlated with unexpected movements in other macroeconomic variables in the model. Drechsel and Tenreyro assume that such movements in commodity prices may have contemporaneous effects on other variables, yet other variables have no contemporaneous impact on commodity prices. The other variables are likewise ordered so that an exogenous “GDP shock” may contemporaneously move consumption, investment, and the balance of trade, but only such a price shock may so move commodity prices. Our counterfactual simulations involve removing the price shocks that affect all endogenous variables, leaving in place those shocks that by assumption do not contemporaneously affect commodity prices.