The Americas Blog seeks to present a more accurate perspective on economic and political developments in the Western Hemisphere than is often presented in the United States. It will provide information that is often ignored, buried, and sometimes misreported in the major U.S. media.

Spanish description lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Nunc in arcu neque. Nulla at est euismod, tempor ligula vitae, luctus justo. Ut auctor mi at orci porta pellentesque. Nunc imperdiet sapien sed orci semper, finibus auctor tellus placerat. Nulla scelerisque feugiat turpis quis venenatis. Curabitur mollis diam eu urna efficitur lobortis.

• BrazilBrasilLatin America and the CaribbeanAmérica Latina y el CaribeUS Foreign PolicyPolítica exterior de EE. UU.

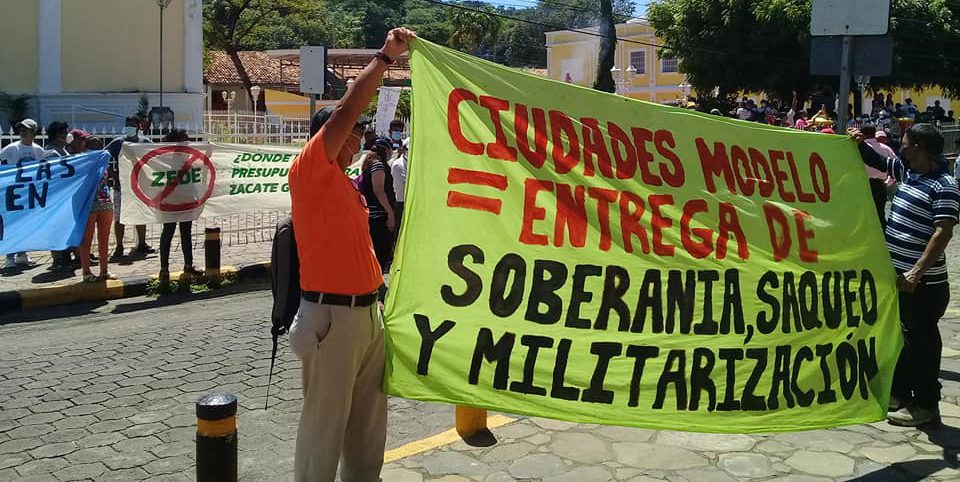

• HondurasHondurasLatin America and the CaribbeanAmérica Latina y el CaribeMexicoMexicoUS Foreign PolicyPolítica exterior de EE. UU.

• GovernmentEl GobiernoHondurasHondurasLatin America and the CaribbeanAmérica Latina y el CaribeWorldEl Mundo

• BoliviaBoliviaDemocracyLatin America and the CaribbeanAmérica Latina y el CaribeMexicoMexicoOrganization of American StatesOrganización de los Estados AmericanosWorldEl Mundo

• BoliviaBoliviaLatin America and the CaribbeanAmérica Latina y el CaribeOrganization of American StatesOrganización de los Estados AmericanosWorldEl Mundo

• BoliviaBoliviaLatin America and the CaribbeanAmérica Latina y el CaribeUS Foreign PolicyPolítica exterior de EE. UU.

The MAS Received More Votes in Almost All of the OAS’s 86 Suspect Precincts in 2020 than in 2019

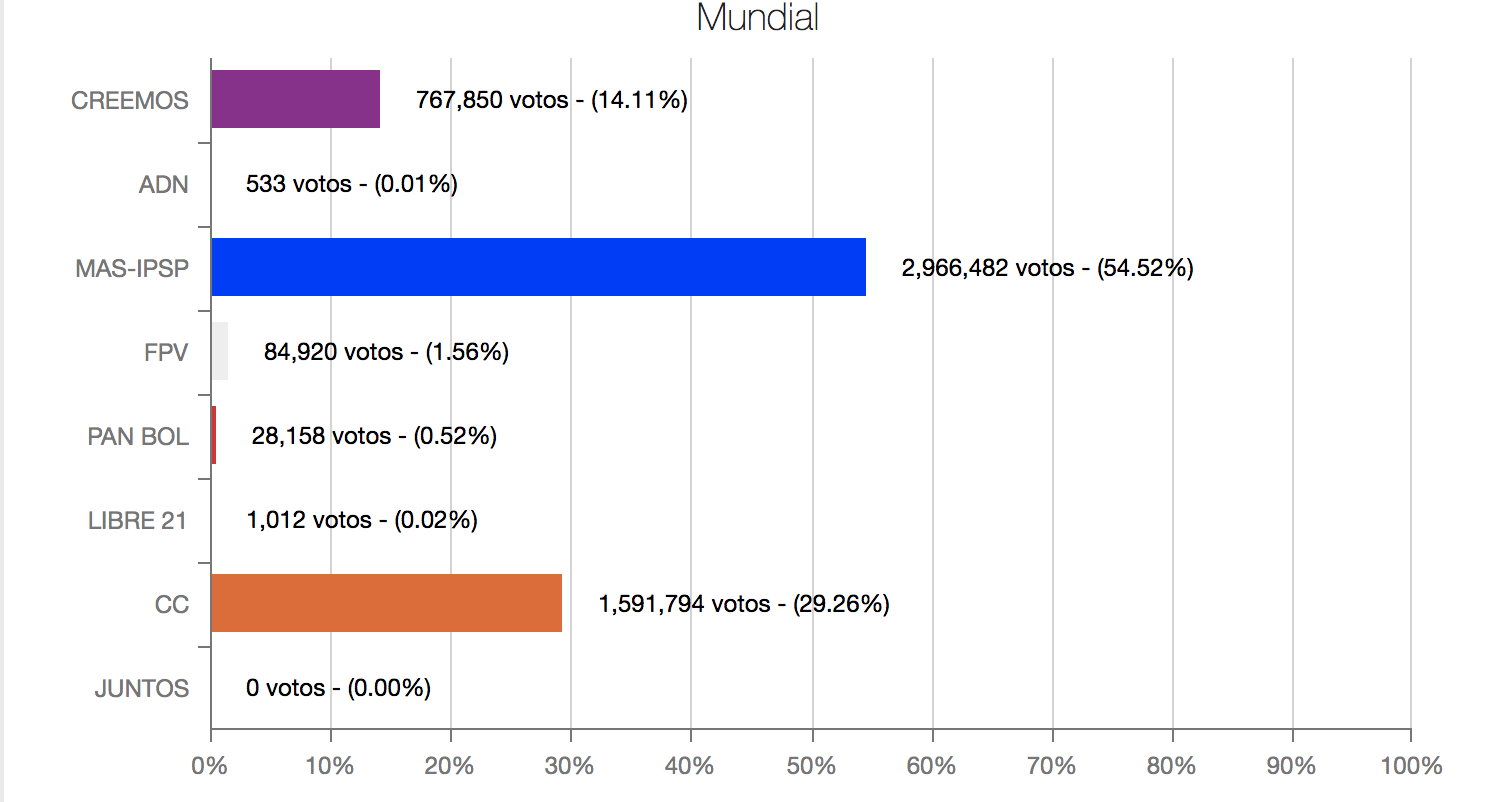

On Sunday, October 20, Bolivians went to the polls and overwhelmingly elected Luis Arce of the MAS party president. Private quick counts released the night of the vote showed Arce receiving more than 50 percent of the vote and holding a more than 20 percentage point lead over second place candidate Carlos Mesa. As of Wednesday morning, just over 88 percent of votes had been tallied in the official results system — and Arce’s lead is even greater. The MAS candidate’s vote share is, at the time of writing, 54.5 compared to 29.3 for Mesa. As the final votes are counted, Arce’s vote share will likely increase further.

At this point, there can be no questioning Arce’s victory. The election came nearly exactly a year after the October 2019 elections which were followed by violent protests and the ouster of then president Evo Morales, who resigned under pressure from the military. Official results in that vote showed Morales and the MAS party winning with a 10.56 percentage point advantage over Mesa, just over the 10 point margin of victory needed for Morales to win the election outright, without having to stand in a run-off election. However, the Organization of American States (OAS) alleged widespread manipulation of the results, feeding a narrative of electoral fraud that served as a pretext for the November 10, 2019 coup.

With Arce’s 2020 victory now all but confirmed, what do the 2020 results tell us about the OAS allegations of fraud in last year’s vote?

The OAS’s initial claims of fraud centered around a “drastic” and “inexplicable” change in the trend of the vote, which allegedly took place after the preliminary results system, or TREP, was suspended for nearly 24 hours. In the time since, myriad statistical analyses — from CEPR (beginning the day after the OAS allegations), and from academics at MIT, Tulane, University of Pennsylvania and elsewhere, have shown the OAS’s statistical analysis to be deeply flawed. In fact, there was no “inexplicable” change in the trend of the vote.

The OAS has refused to respond to these studies, or to queries about their statistical analysis from members of Congress, and has instead pointed to other alleged irregularities identified in the OAS audit. Statistical analysis is just informative, the OAS claimed, but the real evidence was in an audit that they carried out after the elections.

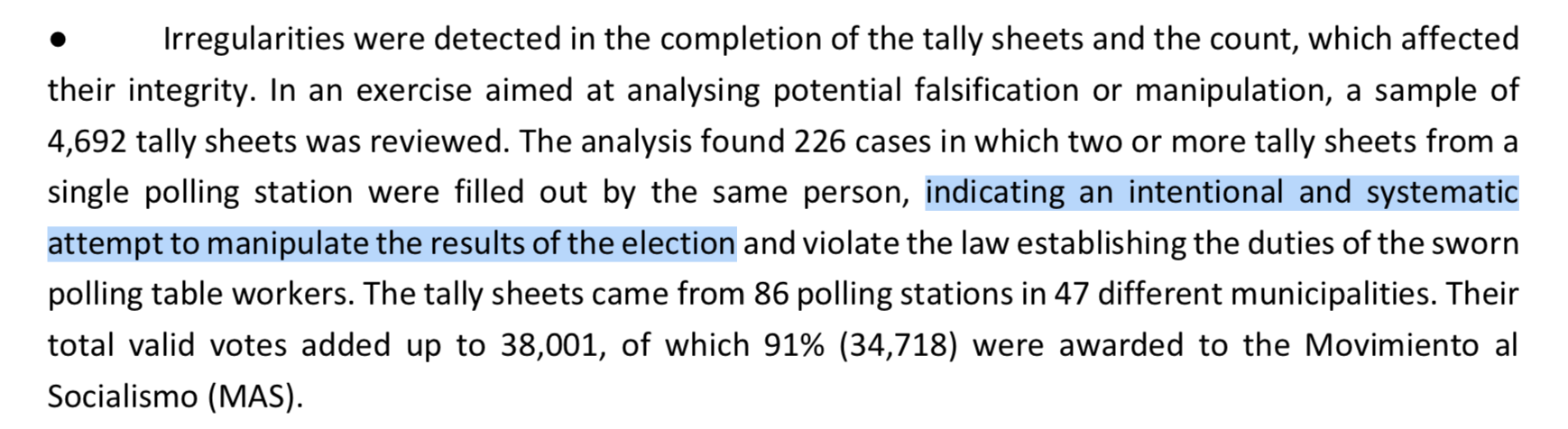

In that audit, the only evidence purporting to show an actual impact on the results of the elections were 226 tally sheets from 86 voting centers across the country. The OAS alleged that the tally sheets had been doctored. They noted that, if you removed the votes for Morales from all of these 226 tally sheets, his entire advantage above the 10 percentage point threshold for a first-round win disappeared. In other words, these 226 tally sheets served as supposed proof that Morales had cheated in order to win in the first round.

Excerpts from the OAS audit report.

In March 2020, CEPR published an 82-page report detailing how the rest of the OAS allegations were just as flawed as the statistical analysis that formed the basis for the fraud narrative that led to Morales’s forced removal from office. We looked into these 226 tally sheets, showing the flaws in the OAS analysis and pointing out that the results in these voting centers closely matched results from previous elections. There was, in fact, nothing surprising about MAS performing extremely well in these areas. Further, we noted that while OAS officials had repeatedly spoken publicly about forged tally sheets, the auditors had provided no evidence to back up that allegation.

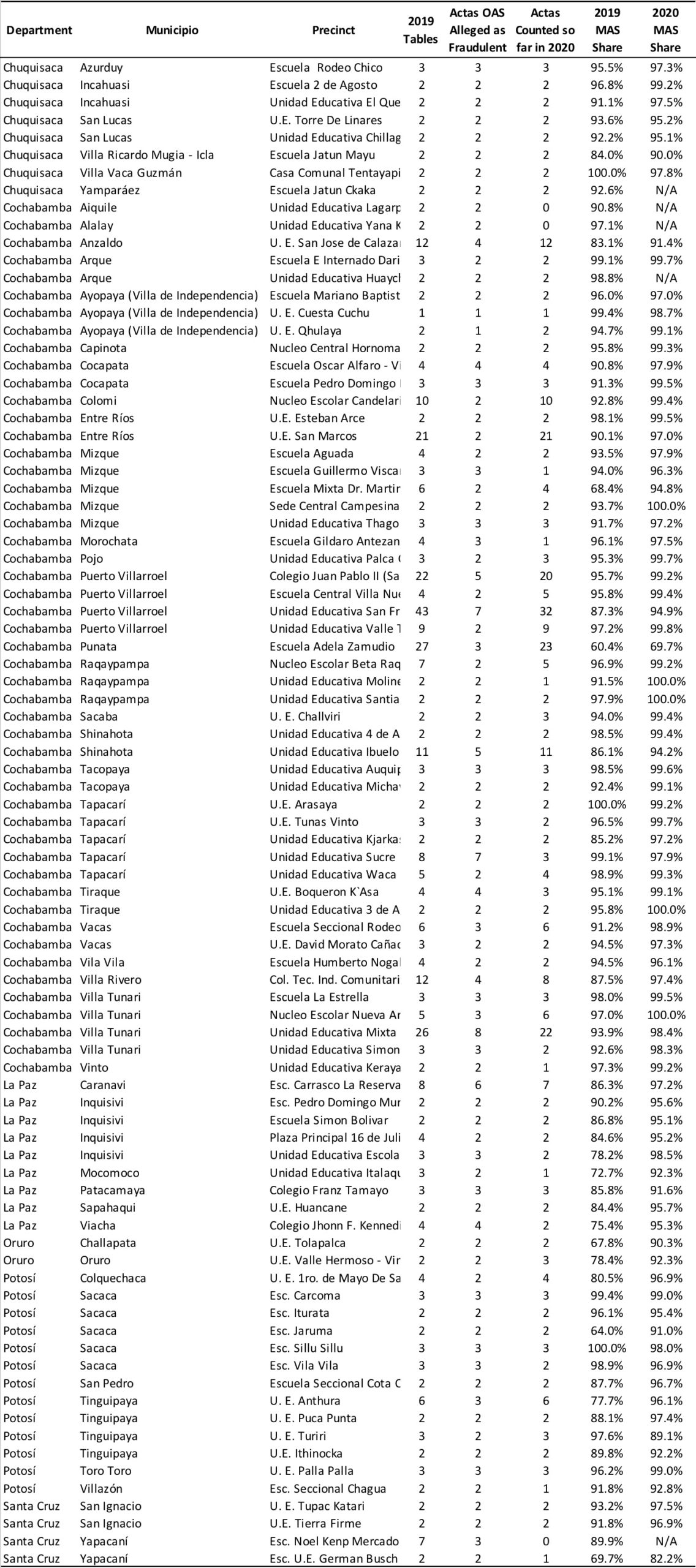

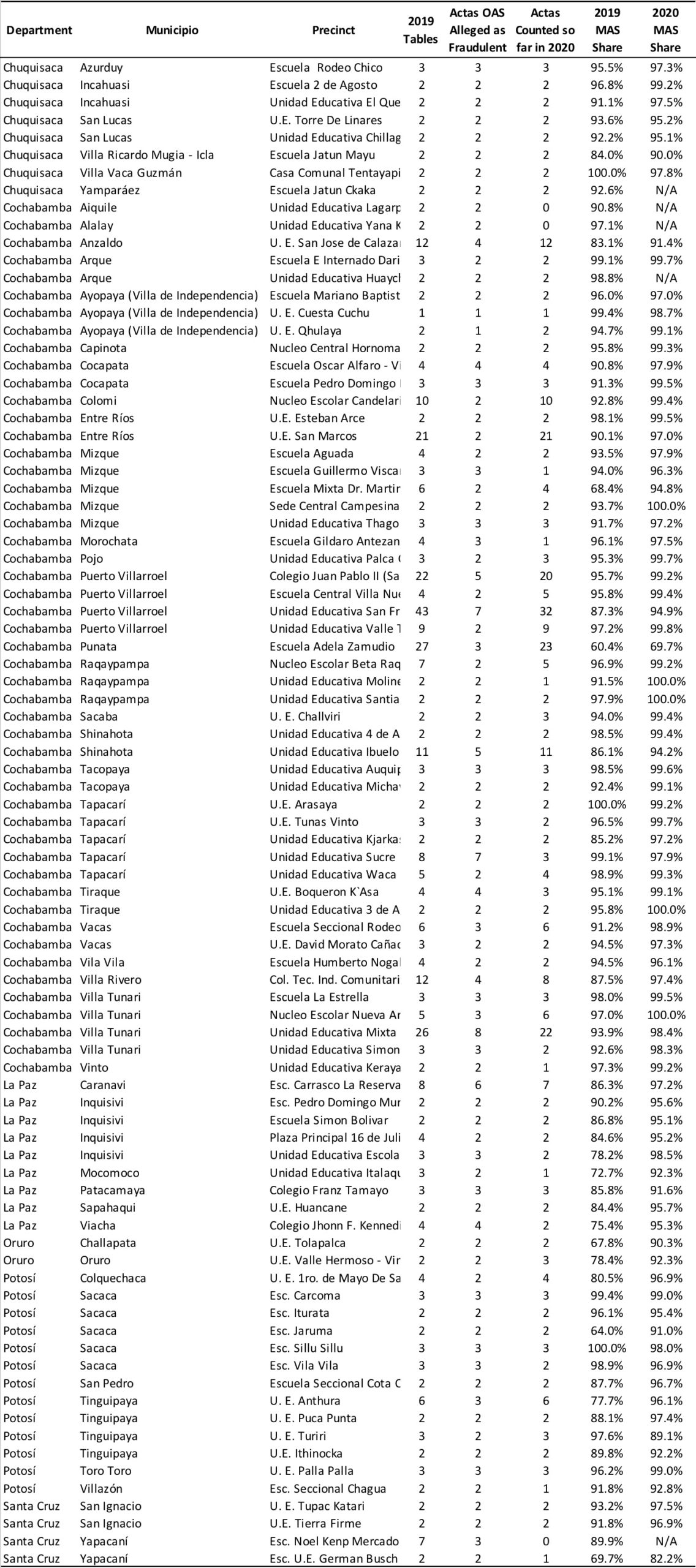

Now that there are disaggregated voting results from this Sunday’s elections, we can see that results in the centers where the OAS had allegedly identified doctored tally sheets follow the same patterns as in the 2019 elections. Table 1, below, presents the 2020 results (with 88 percent of votes counted overall) in all 86 voting centers where the OAS alleged that tally sheets had been manipulated last year.

Table 1.

We have at least partial data for 81 of the 86 voting centers, and in all but 9, the MAS share of the vote has increased when compared to 2019.

In 2019, the OAS and other observers appeared scandalized by the fact that, in many rural areas, Morales had received more than 90 percent of the vote — and in some cases, even 100 percent of the vote. This, they claimed, surely sufficed as evidence of fraud. But, the 2020 results thus far further discredit the unsubstantiated claims made by the OAS, which served as justification for a coup d’etat and the repression that followed. To this day, former electoral officials remain under house arrest based on nothing more than the OAS audit.

As we noted in the March report, the communities targeted in the OAS analysis of these 226 tally sheets are, in the majority of cases, predominantly Indigenous. Though it may come as a shock to see a candidate receive 100 percent of the votes, it shouldn’t. Community voting — in which a community comes to a consensus around who to vote for — is a widely recognized phenomenon in Bolivia.

What the OAS alleged is that electoral jurors, the citizens selected at random by the electoral authorityTSE to serve as electoral officials at each voting table, did not print their names on the tally sheets — but that someone else had written their names. To be clear, the OAS does not allege that all 226 were filled out by the same individual; — in no case does the OAS allege that more than 7 tally sheets were filled out by the same person. Further, in only one of the 226 cases does the OAS allege any problem at all with any signatures on the tally sheets. Rather than fraud, the most likely explanation for this is simply that a notary (each notary oversees about 8 voting tables), or some other official with clear handwriting, printed the names and then each juror signed the tally sheet. It is not clear, from the electoral regulations, that this is even a violation of the electoral law. Either way, the results from 2020 further confirm that there was nothing abnormal about the results on these 226 tally sheets in 2019. Further, what the OAS identified as irregularities had no discernable impact on the results of the election.

We can’t go back to 2019, or erase the racist violence unleashed on the population following the coup. On Sunday, Bolivians showed their courage, and the power of organized social movements, in righting the wrong of 2019. But that victory shouldn’t allow us to forget about 2019, or the role that international actors played in overthrowing a democratically elected government. Those 226 tally sheets never showed fraud, as the OAS asserted. They do, however, reveal how the OAS disenfranchised tens of thousands of Indigenous Bolivians in its galling attempts to justify the undemocratic removal of an elected leader.

The MAS Received More Votes in Almost All of the OAS’s 86 Suspect Precincts in 2020 than in 2019

On Sunday, October 20, Bolivians went to the polls and overwhelmingly elected Luis Arce of the MAS party president. Private quick counts released the night of the vote showed Arce receiving more than 50 percent of the vote and holding a more than 20 percentage point lead over second place candidate Carlos Mesa. As of Wednesday morning, just over 88 percent of votes had been tallied in the official results system — and Arce’s lead is even greater. The MAS candidate’s vote share is, at the time of writing, 54.5 compared to 29.3 for Mesa. As the final votes are counted, Arce’s vote share will likely increase further.

At this point, there can be no questioning Arce’s victory. The election came nearly exactly a year after the October 2019 elections which were followed by violent protests and the ouster of then president Evo Morales, who resigned under pressure from the military. Official results in that vote showed Morales and the MAS party winning with a 10.56 percentage point advantage over Mesa, just over the 10 point margin of victory needed for Morales to win the election outright, without having to stand in a run-off election. However, the Organization of American States (OAS) alleged widespread manipulation of the results, feeding a narrative of electoral fraud that served as a pretext for the November 10, 2019 coup.

With Arce’s 2020 victory now all but confirmed, what do the 2020 results tell us about the OAS allegations of fraud in last year’s vote?

The OAS’s initial claims of fraud centered around a “drastic” and “inexplicable” change in the trend of the vote, which allegedly took place after the preliminary results system, or TREP, was suspended for nearly 24 hours. In the time since, myriad statistical analyses — from CEPR (beginning the day after the OAS allegations), and from academics at MIT, Tulane, University of Pennsylvania and elsewhere, have shown the OAS’s statistical analysis to be deeply flawed. In fact, there was no “inexplicable” change in the trend of the vote.

The OAS has refused to respond to these studies, or to queries about their statistical analysis from members of Congress, and has instead pointed to other alleged irregularities identified in the OAS audit. Statistical analysis is just informative, the OAS claimed, but the real evidence was in an audit that they carried out after the elections.

In that audit, the only evidence purporting to show an actual impact on the results of the elections were 226 tally sheets from 86 voting centers across the country. The OAS alleged that the tally sheets had been doctored. They noted that, if you removed the votes for Morales from all of these 226 tally sheets, his entire advantage above the 10 percentage point threshold for a first-round win disappeared. In other words, these 226 tally sheets served as supposed proof that Morales had cheated in order to win in the first round.

Excerpts from the OAS audit report.

In March 2020, CEPR published an 82-page report detailing how the rest of the OAS allegations were just as flawed as the statistical analysis that formed the basis for the fraud narrative that led to Morales’s forced removal from office. We looked into these 226 tally sheets, showing the flaws in the OAS analysis and pointing out that the results in these voting centers closely matched results from previous elections. There was, in fact, nothing surprising about MAS performing extremely well in these areas. Further, we noted that while OAS officials had repeatedly spoken publicly about forged tally sheets, the auditors had provided no evidence to back up that allegation.

Now that there are disaggregated voting results from this Sunday’s elections, we can see that results in the centers where the OAS had allegedly identified doctored tally sheets follow the same patterns as in the 2019 elections. Table 1, below, presents the 2020 results (with 88 percent of votes counted overall) in all 86 voting centers where the OAS alleged that tally sheets had been manipulated last year.

Table 1.

We have at least partial data for 81 of the 86 voting centers, and in all but 9, the MAS share of the vote has increased when compared to 2019.

In 2019, the OAS and other observers appeared scandalized by the fact that, in many rural areas, Morales had received more than 90 percent of the vote — and in some cases, even 100 percent of the vote. This, they claimed, surely sufficed as evidence of fraud. But, the 2020 results thus far further discredit the unsubstantiated claims made by the OAS, which served as justification for a coup d’etat and the repression that followed. To this day, former electoral officials remain under house arrest based on nothing more than the OAS audit.

As we noted in the March report, the communities targeted in the OAS analysis of these 226 tally sheets are, in the majority of cases, predominantly Indigenous. Though it may come as a shock to see a candidate receive 100 percent of the votes, it shouldn’t. Community voting — in which a community comes to a consensus around who to vote for — is a widely recognized phenomenon in Bolivia.

What the OAS alleged is that electoral jurors, the citizens selected at random by the electoral authorityTSE to serve as electoral officials at each voting table, did not print their names on the tally sheets — but that someone else had written their names. To be clear, the OAS does not allege that all 226 were filled out by the same individual; — in no case does the OAS allege that more than 7 tally sheets were filled out by the same person. Further, in only one of the 226 cases does the OAS allege any problem at all with any signatures on the tally sheets. Rather than fraud, the most likely explanation for this is simply that a notary (each notary oversees about 8 voting tables), or some other official with clear handwriting, printed the names and then each juror signed the tally sheet. It is not clear, from the electoral regulations, that this is even a violation of the electoral law. Either way, the results from 2020 further confirm that there was nothing abnormal about the results on these 226 tally sheets in 2019. Further, what the OAS identified as irregularities had no discernable impact on the results of the election.

We can’t go back to 2019, or erase the racist violence unleashed on the population following the coup. On Sunday, Bolivians showed their courage, and the power of organized social movements, in righting the wrong of 2019. But that victory shouldn’t allow us to forget about 2019, or the role that international actors played in overthrowing a democratically elected government. Those 226 tally sheets never showed fraud, as the OAS asserted. They do, however, reveal how the OAS disenfranchised tens of thousands of Indigenous Bolivians in its galling attempts to justify the undemocratic removal of an elected leader.

• BoliviaBoliviaLatin America and the CaribbeanAmérica Latina y el CaribeWorldEl Mundo

• BoliviaBoliviaLatin America and the CaribbeanAmérica Latina y el CaribeOrganization of American StatesOrganización de los Estados Americanos