The Americas Blog seeks to present a more accurate perspective on economic and political developments in the Western Hemisphere than is often presented in the United States. It will provide information that is often ignored, buried, and sometimes misreported in the major U.S. media.

Spanish description lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Nunc in arcu neque. Nulla at est euismod, tempor ligula vitae, luctus justo. Ut auctor mi at orci porta pellentesque. Nunc imperdiet sapien sed orci semper, finibus auctor tellus placerat. Nulla scelerisque feugiat turpis quis venenatis. Curabitur mollis diam eu urna efficitur lobortis.

• BoliviaBoliviaLatin America and the CaribbeanAmérica Latina y el CaribeWorldEl Mundo

• BoliviaBoliviaBrazilBrasilEcuadorEcuadorGovernmentEl GobiernoHondurasHondurasLatin America and the CaribbeanAmérica Latina y el CaribeWorldEl Mundo

• EcuadorEcuadorLatin America and the CaribbeanAmérica Latina y el CaribeUS Foreign PolicyPolítica exterior de EE. UU.WorldEl Mundo

• Latin America and the CaribbeanAmérica Latina y el CaribeUS Foreign PolicyPolítica exterior de EE. UU.WorldEl Mundo

• BrazilBrasilLatin America and the CaribbeanAmérica Latina y el CaribeWorldEl Mundo

• BoliviaBoliviaCOVID-19CoronavirusLatin America and the CaribbeanAmérica Latina y el CaribeWorldEl Mundo

• COVID-19CoronavirusGlobalization and TradeGlobalización y comercioLatin America and the CaribbeanAmérica Latina y el CaribeWorldEl Mundo

• COVID-19CoronavirusLatin America and the CaribbeanAmérica Latina y el CaribeUS Foreign PolicyPolítica exterior de EE. UU.

On Tuesday, in a comment to CEPR’s Americas Blog, an Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) spokesperson confirmed that the agency had run 112 deportation flights to 13 countries during an eight-week period beginning in early March. This is the first on-the-record comment from ICE confirming the extent of the agency’s deportations.

Since late April, CEPR has maintained a database of “likely” ICE Air deportation flights to Latin America and the Caribbean (updated daily and available here). Though ICE did not provide a detailed accounting of individual flights, the overall numbers provided by ICE almost exactly match those in the CEPR database.

From March 8 to May 9, the ICE spokesperson said the agency had run 112 deportation flights to 13 countries, including 12 in Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC). The only country outside the region to receive a deportation flight was Liberia; ICE deported a known human rights-abuser on a charter flight in late April. That leaves 111 flights to the LAC region; over the same period, the CEPR database includes 110 unique flights (as some flights make multiple stops, the database shows flights to 116 destinations).

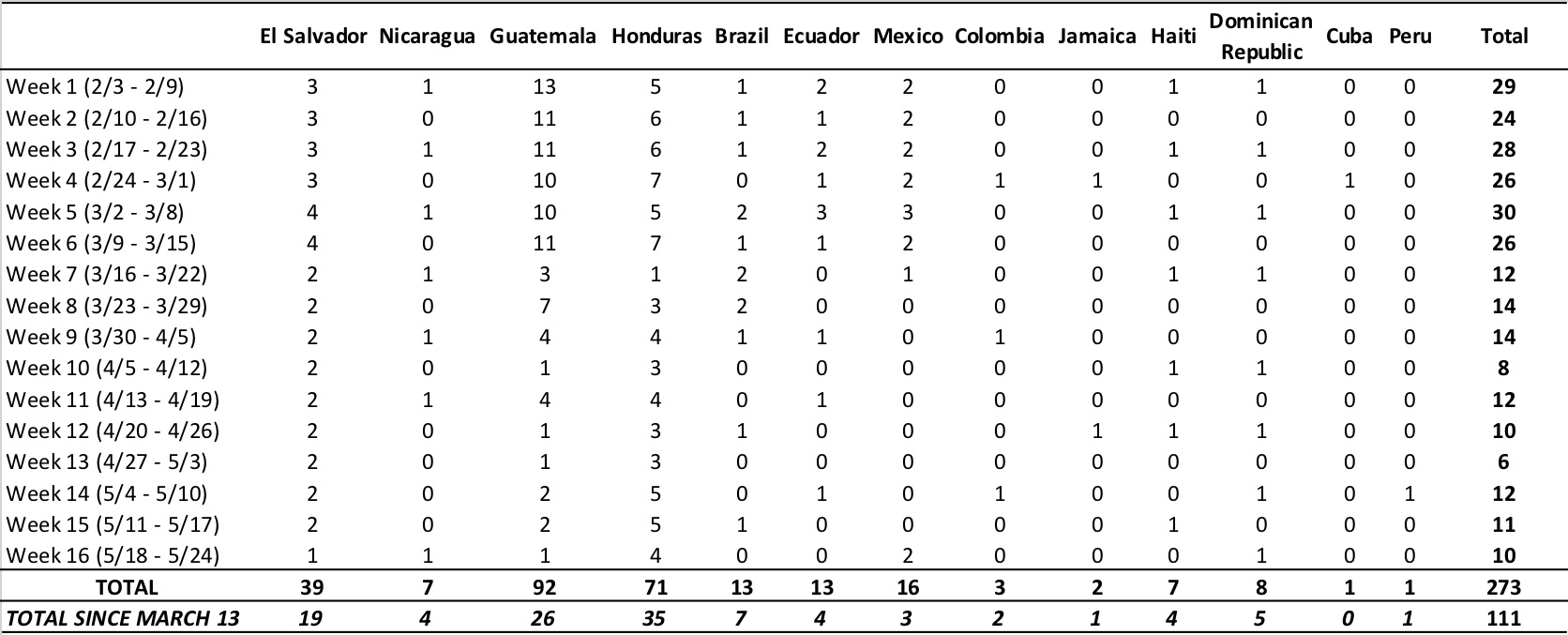

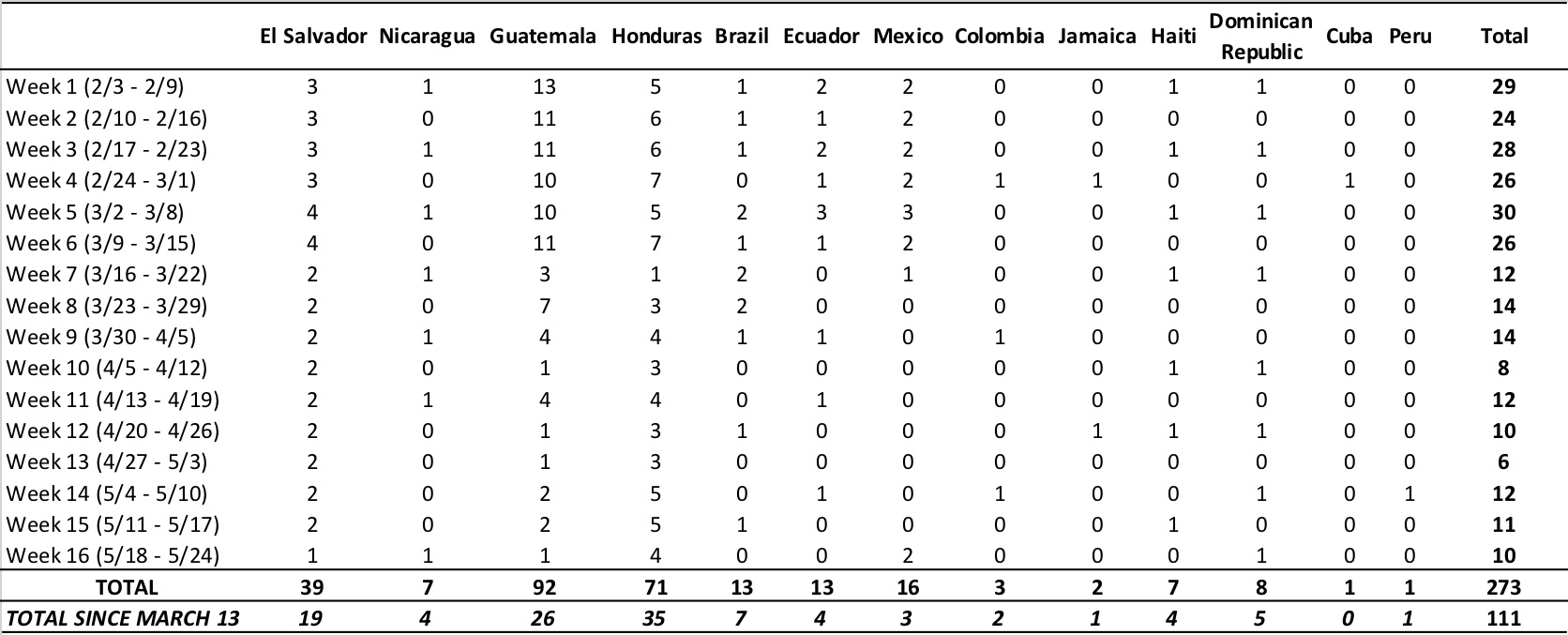

Each flight in the CEPR ICE Air Database can be seen in the graphic below. From February 3 through May 20, the database includes 273 likely ICE Air deportation flights to the LAC region.

US Ramping up Deportations?

Following the Trump administration’s designation of a national emergency on March 13, the number of deportation flights fell, and one of the charter plane companies appeared to stop operating on behalf of ICE. Members of Congress and international human rights organizations have called on the Trump administration to halt deportations, which threaten to spread the disease even further and prolong the pandemic.

However, recent trends indicate the US may be once again ramping up deportations even as the number of confirmed cases continues to rise globally — and within ICE detention centers in the United States. Though ICE has claimed it is following medical guidelines, those guidelines have not stopped the US from continuing to export COVID-19 through its deportation flights. In the last two weeks, three countries in the region received deportation flights after prolonged breaks.

On May 7, ICE deported 27 Peruvians on a Swift Air charter plane. Peru was not among the countries with regularly scheduled deportation flights in fiscal year 2019, and the CEPR ICE Air database contains no other likely deportation flights to Peru since February. In a comment to CEPR, however, an ICE spokesperson said that the US had deported 253 Peruvians in fiscal year 2020 as of May 2 — indicating the recent Peru flight is likely the restart of an existing route.

Source: Flightaware.com and author’s calculations. Note: Week 16 data is only through 5/20.

This week also saw the resumption of deportations to Managua, Nicaragua. The country had received one flight every two weeks until mid-April. The flight this week was the first in 34 days.

On May 19, two Swift Air planes flew to Mexico City: one from Brownsville, Texas and another from San Diego, California. The next day, the Mexican government confirmed that those were the first of eight flights planned over the next ten days. With the flights to Peru, Nicaragua and Mexico, ICE has now operated deportation flights to 11 countries in the region so far in the month of May.

It also now appears that the US is once again operating deportation flights to destinations outside the LAC region. On May 19, 167 Indian nationals were flown on an Omni Air charter plane to Sri Guru Ram Das International Airport in Armitsar, in India’s Punjab province — the only known deportation outside the region other than the earlier flight to Liberia.

On May 15, the Department of Homeland Security exercised an option on its charter flight contract valued at $50 million. The option brings the total allocated under Classic Air Charter’s (CAC) contract to $346.5 million.

On Tuesday, in a comment to CEPR’s Americas Blog, an Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) spokesperson confirmed that the agency had run 112 deportation flights to 13 countries during an eight-week period beginning in early March. This is the first on-the-record comment from ICE confirming the extent of the agency’s deportations.

Since late April, CEPR has maintained a database of “likely” ICE Air deportation flights to Latin America and the Caribbean (updated daily and available here). Though ICE did not provide a detailed accounting of individual flights, the overall numbers provided by ICE almost exactly match those in the CEPR database.

From March 8 to May 9, the ICE spokesperson said the agency had run 112 deportation flights to 13 countries, including 12 in Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC). The only country outside the region to receive a deportation flight was Liberia; ICE deported a known human rights-abuser on a charter flight in late April. That leaves 111 flights to the LAC region; over the same period, the CEPR database includes 110 unique flights (as some flights make multiple stops, the database shows flights to 116 destinations).

Each flight in the CEPR ICE Air Database can be seen in the graphic below. From February 3 through May 20, the database includes 273 likely ICE Air deportation flights to the LAC region.

US Ramping up Deportations?

Following the Trump administration’s designation of a national emergency on March 13, the number of deportation flights fell, and one of the charter plane companies appeared to stop operating on behalf of ICE. Members of Congress and international human rights organizations have called on the Trump administration to halt deportations, which threaten to spread the disease even further and prolong the pandemic.

However, recent trends indicate the US may be once again ramping up deportations even as the number of confirmed cases continues to rise globally — and within ICE detention centers in the United States. Though ICE has claimed it is following medical guidelines, those guidelines have not stopped the US from continuing to export COVID-19 through its deportation flights. In the last two weeks, three countries in the region received deportation flights after prolonged breaks.

On May 7, ICE deported 27 Peruvians on a Swift Air charter plane. Peru was not among the countries with regularly scheduled deportation flights in fiscal year 2019, and the CEPR ICE Air database contains no other likely deportation flights to Peru since February. In a comment to CEPR, however, an ICE spokesperson said that the US had deported 253 Peruvians in fiscal year 2020 as of May 2 — indicating the recent Peru flight is likely the restart of an existing route.

Source: Flightaware.com and author’s calculations. Note: Week 16 data is only through 5/20.

This week also saw the resumption of deportations to Managua, Nicaragua. The country had received one flight every two weeks until mid-April. The flight this week was the first in 34 days.

On May 19, two Swift Air planes flew to Mexico City: one from Brownsville, Texas and another from San Diego, California. The next day, the Mexican government confirmed that those were the first of eight flights planned over the next ten days. With the flights to Peru, Nicaragua and Mexico, ICE has now operated deportation flights to 11 countries in the region so far in the month of May.

It also now appears that the US is once again operating deportation flights to destinations outside the LAC region. On May 19, 167 Indian nationals were flown on an Omni Air charter plane to Sri Guru Ram Das International Airport in Armitsar, in India’s Punjab province — the only known deportation outside the region other than the earlier flight to Liberia.

On May 15, the Department of Homeland Security exercised an option on its charter flight contract valued at $50 million. The option brings the total allocated under Classic Air Charter’s (CAC) contract to $346.5 million.

• ArgentinaArgentinaIMFFondo Monetario Internacional

For those following Argentina’s debt saga, the current situation might seem eerily familiar: after the implosion of an IMF program, Argentina finds itself at the brink of default, with a debt burden, denominated in foreign currencies, that it simply cannot pay. In contrast with Argentina’s default in 2001, when it reached agreements with most of its creditors years later, this time Argentina’s government is doing its best to avoid default by attempting to find agreement with its lenders for an orderly restructuring.

Argentina made its creditors an offer based on a sound framework that aims to restore debt sustainability. The offer proposed a three-year stay on all payments, followed by a gradual resumption in interest repayments as the economy recovers, along with a 0.4 percent write-off of the capital value of the bonds. Creditors now have a choice between accepting this offer or letting Argentina default as negotiations drag on.

To understand why this offer is the best Argentina can do, one needs to understand the dire situation its economy is in. Until Argentina can revive its economy, it truly does not have enough revenue to service its dollar-denominated debt. Negotiations or costly litigation might drag on. And even if creditors get a better deal on paper, it does not matter if Argentina cannot honor it.

Between 2017 and 2019, the ratio of external debt-to-GDP exploded: from 38.8 percent in 2017, to 69 percent in 2019. This was caused by a sharp depreciation of the peso, along with a contraction of the economy. These numbers will only get much worse this year as Argentina battles COVID-19. This additional shock is not only hurting Argentina’s domestic economy but has also caused a collapse in commodity prices, Argentina’s main source of exports.

It is clear that Argentina’s debt is unpayable and needs to be restructured. The IMF released its own debt sustainability analysis, which reached the same conclusion as the Argentine government: the debt is unsustainable and there is no scope for any foreign currency payments for at least the next three years. The most important implication of this assessment is that the IMF will no longer lend any funds to Argentina before a debt restructuring occurs, as its own rules forbid it from lending to countries with unsustainable debt.

Argentina’s private creditors need to accept that they will not receive their agreed-upon returns as there is currently no one left to bail them out. A restructuring could have taken place at more favorable terms if it had occurred before the IMF started its record $56 billion program in the summer of 2018. To most observers, it was already clear then that Argentina’s debt was unsustainable. Yet, the IMF bent its own rules and officially assessed Argentina’s debt to be “sustainable but not with a high probability.” This decision was made on political grounds, as the Trump administration was committed to the IMF supporting then president Mauricio Macri.

The roots of this crisis can be traced back to mistakes made by the Macri administration, in office from 2015 to 2019. Before Macri, Argentina was locked out of international credit markets due to a legal dispute with holdouts from its previous debt restructuring. The vulture funds — hedge funds that buy distressed debt and then take legal action to recover the full face value of the bonds — managed to hold Argentina hostage due to a 2014 ruling by a US court that Argentina could not repay any creditors until it paid the holdouts. Macri, who was elected on a “market-friendly” platform, was quick to settle the dispute and pay the vulture funds, with some making profits as high as 1200 percent.

Another step Macri took that would later prove disastrous was his immediate removal of all capital control measures. At first, markets cheered this, and Argentina issued over $40 billion in dollar-denominated bonds, mostly under US law. While markets lent him more dollars, Argentina continued to have limited sources of dollar revenue, and there were no significant investments in growing Argentina’s export base. Argentina’s macroeconomic imbalances were revealed when a brief rise in US interest rates precipitated capital outflows from emerging markets.

The large and sudden reversal in capital flows from Argentina caused a collapse of the peso, as the Central Bank stumbled to defend its currency, spending billions of dollars to no avail. It is then that the Macri administration approached the IMF, which ignored the debt sustainability issues and proceeded to sign an agreement of $56 billion, out of which about $44 billion was eventually disbursed. Most of the funds disbursed immediately left the country, enabling many investors to cash out of Argentina at little or no loss.

Meanwhile, Argentina was stuck with additional foreign exchange debt and an economic collapse exacerbated by IMF-imposed austerity. The cuts dictated by the IMF worsened the recession and failed to reduce Argentina’s deficit, as revenues collapsed along with the economy. The program also had enormous social costs, as poverty jumped from 27.3 percent in 2018 to over 35 percent at the end of 2019.

Argentina is entering its third year of recession as it now also battles the crisis triggered by COVID-19. In the last four years, Argentina reduced its primary expenditures by over 5 percent, negatively impacting its economy and thus failing to allow room to reduce the budget deficit. There is no more space for additional fiscal consolidation without deepening the economic crisis, and in the current context of a health emergency, without putting more lives at risk. For Argentina to generate revenue to repay its debt, it first needs the space for an economic recovery.

Given this national context, along with the unfavorable global economic situation, it is easy to conclude that Argentina is doing the best it can to do right by its people and by its creditors.

For those following Argentina’s debt saga, the current situation might seem eerily familiar: after the implosion of an IMF program, Argentina finds itself at the brink of default, with a debt burden, denominated in foreign currencies, that it simply cannot pay. In contrast with Argentina’s default in 2001, when it reached agreements with most of its creditors years later, this time Argentina’s government is doing its best to avoid default by attempting to find agreement with its lenders for an orderly restructuring.

Argentina made its creditors an offer based on a sound framework that aims to restore debt sustainability. The offer proposed a three-year stay on all payments, followed by a gradual resumption in interest repayments as the economy recovers, along with a 0.4 percent write-off of the capital value of the bonds. Creditors now have a choice between accepting this offer or letting Argentina default as negotiations drag on.

To understand why this offer is the best Argentina can do, one needs to understand the dire situation its economy is in. Until Argentina can revive its economy, it truly does not have enough revenue to service its dollar-denominated debt. Negotiations or costly litigation might drag on. And even if creditors get a better deal on paper, it does not matter if Argentina cannot honor it.

Between 2017 and 2019, the ratio of external debt-to-GDP exploded: from 38.8 percent in 2017, to 69 percent in 2019. This was caused by a sharp depreciation of the peso, along with a contraction of the economy. These numbers will only get much worse this year as Argentina battles COVID-19. This additional shock is not only hurting Argentina’s domestic economy but has also caused a collapse in commodity prices, Argentina’s main source of exports.

It is clear that Argentina’s debt is unpayable and needs to be restructured. The IMF released its own debt sustainability analysis, which reached the same conclusion as the Argentine government: the debt is unsustainable and there is no scope for any foreign currency payments for at least the next three years. The most important implication of this assessment is that the IMF will no longer lend any funds to Argentina before a debt restructuring occurs, as its own rules forbid it from lending to countries with unsustainable debt.

Argentina’s private creditors need to accept that they will not receive their agreed-upon returns as there is currently no one left to bail them out. A restructuring could have taken place at more favorable terms if it had occurred before the IMF started its record $56 billion program in the summer of 2018. To most observers, it was already clear then that Argentina’s debt was unsustainable. Yet, the IMF bent its own rules and officially assessed Argentina’s debt to be “sustainable but not with a high probability.” This decision was made on political grounds, as the Trump administration was committed to the IMF supporting then president Mauricio Macri.

The roots of this crisis can be traced back to mistakes made by the Macri administration, in office from 2015 to 2019. Before Macri, Argentina was locked out of international credit markets due to a legal dispute with holdouts from its previous debt restructuring. The vulture funds — hedge funds that buy distressed debt and then take legal action to recover the full face value of the bonds — managed to hold Argentina hostage due to a 2014 ruling by a US court that Argentina could not repay any creditors until it paid the holdouts. Macri, who was elected on a “market-friendly” platform, was quick to settle the dispute and pay the vulture funds, with some making profits as high as 1200 percent.

Another step Macri took that would later prove disastrous was his immediate removal of all capital control measures. At first, markets cheered this, and Argentina issued over $40 billion in dollar-denominated bonds, mostly under US law. While markets lent him more dollars, Argentina continued to have limited sources of dollar revenue, and there were no significant investments in growing Argentina’s export base. Argentina’s macroeconomic imbalances were revealed when a brief rise in US interest rates precipitated capital outflows from emerging markets.

The large and sudden reversal in capital flows from Argentina caused a collapse of the peso, as the Central Bank stumbled to defend its currency, spending billions of dollars to no avail. It is then that the Macri administration approached the IMF, which ignored the debt sustainability issues and proceeded to sign an agreement of $56 billion, out of which about $44 billion was eventually disbursed. Most of the funds disbursed immediately left the country, enabling many investors to cash out of Argentina at little or no loss.

Meanwhile, Argentina was stuck with additional foreign exchange debt and an economic collapse exacerbated by IMF-imposed austerity. The cuts dictated by the IMF worsened the recession and failed to reduce Argentina’s deficit, as revenues collapsed along with the economy. The program also had enormous social costs, as poverty jumped from 27.3 percent in 2018 to over 35 percent at the end of 2019.

Argentina is entering its third year of recession as it now also battles the crisis triggered by COVID-19. In the last four years, Argentina reduced its primary expenditures by over 5 percent, negatively impacting its economy and thus failing to allow room to reduce the budget deficit. There is no more space for additional fiscal consolidation without deepening the economic crisis, and in the current context of a health emergency, without putting more lives at risk. For Argentina to generate revenue to repay its debt, it first needs the space for an economic recovery.

Given this national context, along with the unfavorable global economic situation, it is easy to conclude that Argentina is doing the best it can to do right by its people and by its creditors.

• COVID-19CoronavirusLatin America and the CaribbeanAmérica Latina y el CaribeUS Foreign PolicyPolítica exterior de EE. UU.