The Americas Blog seeks to present a more accurate perspective on economic and political developments in the Western Hemisphere than is often presented in the United States. It will provide information that is often ignored, buried, and sometimes misreported in the major U.S. media.

Spanish description lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Nunc in arcu neque. Nulla at est euismod, tempor ligula vitae, luctus justo. Ut auctor mi at orci porta pellentesque. Nunc imperdiet sapien sed orci semper, finibus auctor tellus placerat. Nulla scelerisque feugiat turpis quis venenatis. Curabitur mollis diam eu urna efficitur lobortis.

• COVID-19CoronavirusLatin America and the CaribbeanAmérica Latina y el CaribeUS Foreign PolicyPolítica exterior de EE. UU.

• COVID-19CoronavirusLatin America and the CaribbeanAmérica Latina y el CaribeUS Foreign PolicyPolítica exterior de EE. UU.

There were 232 likely ICE Air deportation flights to Latin America and Caribbean countries between February 3, 2020 and April 24, 2020, CEPR analysis shows.

In 2019, Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) deported 267,258 individuals — 96 percent of whom were from the Latin America and Caribbean region. Though much of the media focus has been on Mexico (49.7 percent of the total) and the Central American nations of Guatemala, Honduras, and El Salvador (together 45.1 percent of the total), ICE deported at least one person to every country in the LAC region in 2019. Ten countries in the region accepted regular deportation flights conducted by ICE’s air operations — known as “ICE Air” — last year.

While the vast majority of deportations to Mexico take place over land, ICE Air flies tens of thousands of people across the country and across the world each year. Amid the global pandemic, which has led to countries shutting down air travel and closing borders, ICE Air continues to deport thousands of immigrants held in detention centers throughout the United States. Those facilities themselves have become hotspots of COVID-19 outbreaks, meaning the US is now exporting the virus to countries throughout the region.

Despite the prevalence of ICE Air deportation flights, and the grave risk to public health that their continuation during the global pandemic presents, little is known about their frequency and destinations. However, a new analysis of flight tracker data sheds some much-needed light on the scope of ICE Air flights and the extent to which countries in Latin America and the Caribbean are affected by continued deportations. Since the Trump administration declared a national emergency on March 13, one ICE Air contractor has flown at least 72 likely deportation flights to 11 Latin America and Caribbean nations — including to Brazil and Ecuador, which are suffering the region’s worst outbreaks of COVID-19, and which have both experienced an increase in deportation flights under the Trump administration.

From March 15 to April 24, ICE Air appears to have made 21 deportation flights to Guatemala; 18 to Honduras; 12 to El Salvador; six to Brazil; three each to Nicaragua, Ecuador, Haiti, and the Dominican Republic; and one each to Colombia and Jamaica. All likely ICE Air deportation flights since February can be seen in the interactive map below.

In 2019, researchers from the University of Washington Center for Human Rights (UWCHR) obtained ICE flight records from 2010 to 2018 following a Freedom of Information Act request. The UWCHR analysis provided the most complete analysis of the extent of ICE Air operations, and their full dataset is available here. Their report also revealed that two private charter companies — Swift Air and Western Atlantic Airlines — conducted the majority of ICE Air deportation flights as subcontractors.

The data analyzed in this post was collected from Flight Aware, a public flight tracker database. Because both Swift and Western perform regular charter services, not all of their flights are part of ICE’s deportation system. However, the flights included in this analysis match known deportation trips, depart from airports known to be used for deportation flights, and follow routes known to be associated with the transport of ICE detainees. While it is possible some of the flights included here were not deportations, it is more likely that this data represents an underestimate of the extent of ICE Air’s operations. ICE is also known to use commercial airlines for deportations and it remains possible that additional charter companies are contracted by ICE. In fiscal year 2017 more than 85 percent of ICE Air deportations were conducted through charter services, according to the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) Inspector General.

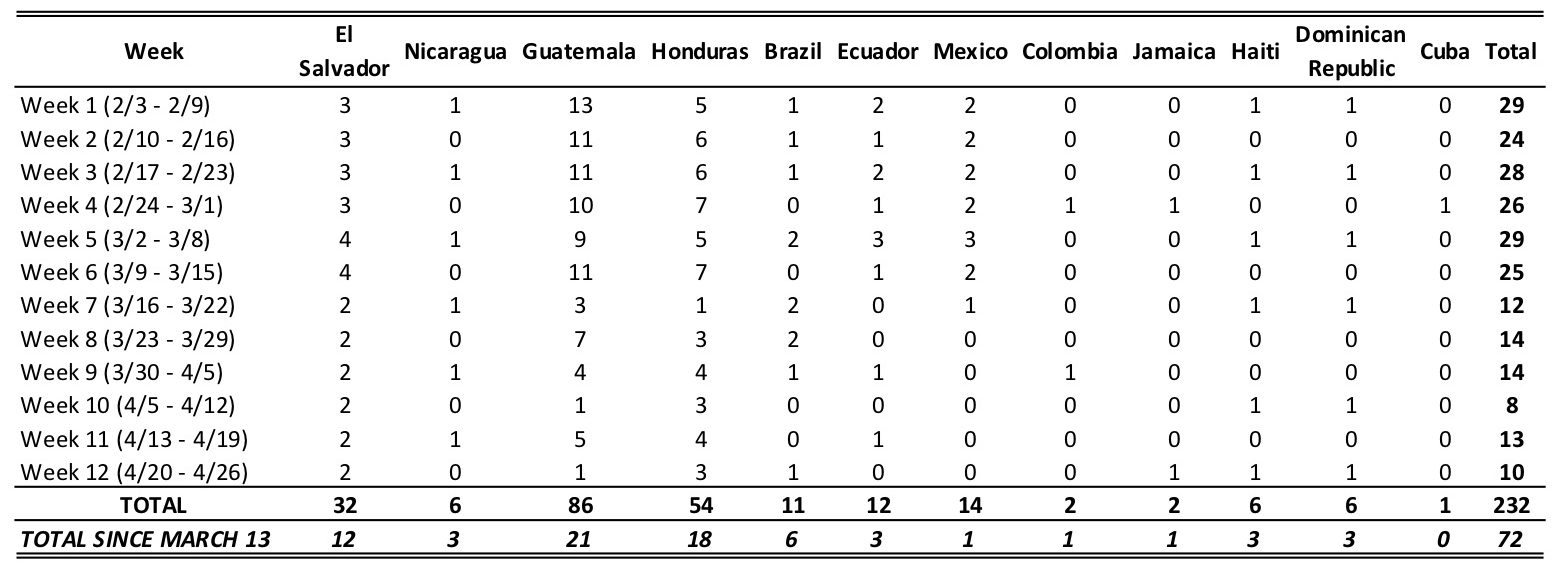

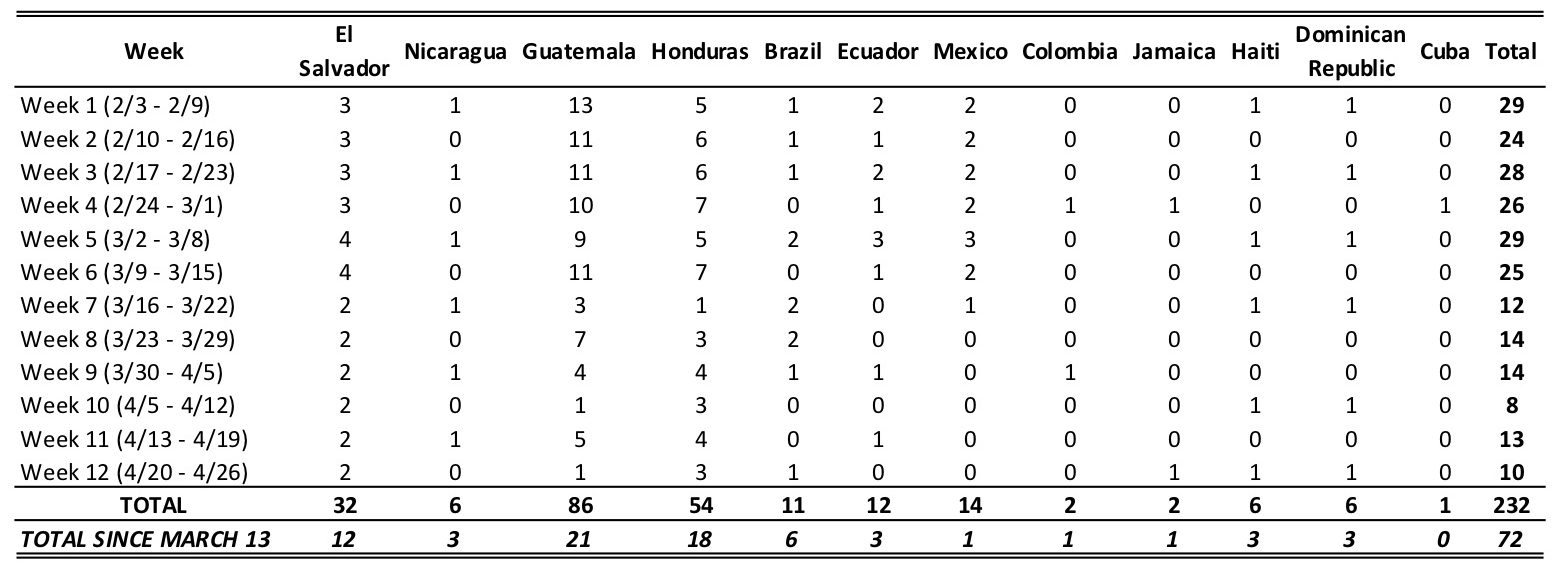

In the first three months of 2020, ICE deported an average of 20,833 individuals each month — on pace for a similar annual number as in 2019. In contrast, the Washington Post reported that in the first 11 days of April 2020, ICE deported 2,985 people — less than half that rate. Indeed, the flight tracking data analyzed here shows a decrease in deportation flights beginning around March 13 — as can be seen in the table below.

Table 1. ICE Air Likely Deportation Flights, by Week

Source: Flight Aware, author’s calculation.

The drop visible in the table above appears to result from the stoppage of Western Atlantic’s international charter flights on March 13 — when the US declared a national emergency. ICE Air’s other subcontractor, Swift Air, has continued flying. Despite growing restrictions on international air travel, Swift had almost exactly as many flights from the US to Latin America and the Caribbean in March as it did in February — though that number has decreased some in April. (In recent months, Swift-owned airplanes have made trips to an additional number of countries in the region, including Cuba, Suriname, Peru, Bolivia, Trinidad and Tobago, Aruba, Belize, and Grenada; however those flights did not match up with known deportation flights and have been excluded from the analysis.)

Though much attention has been paid to recent deportation flights to Guatemala and Haiti — both countries have reported confirmed COVID-19 cases among those deported — the data reveal that many other countries are likely experiencing the same phenomenon.

In 2019, the Trump administration began ICE Air deportations to Brazil, which had previously blocked such flights. The United States relies on foreign governments to approve deportation flights, and under the leadership of Trump-ally Jair Bolsonaro, Brazil acquiesced. Flight data indicate that those flights have continued during the pandemic. Since March 13, there have been six flights conducted by Swift Air to Belo Horizonte, Brazil — the destination of previously reported deportation flights. Brazil is currently experiencing the largest outbreak of COVID-19 in the region.

Some of the Swift Air flights to Brazil have first made a stop in Ecuador’s port city Guayaquil — home to perhaps the deadliest outbreak of COVID-19 in the world. Deportations to Ecuador increased by 78 percent in 2019 compared to the year prior as, similar to the Brazilian government, Ecuador has sought to bolster relations with the Trump administration. As can be seen in the table above, likely deportation flights to Ecuador have decreased since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. However, there have still been three since March 13 — including an April 17 flight to Quito that contained at least 70 individuals, according to immigration attorneys.

Interestingly, while deportations to Mexico have continued — one recent deportee has since tested positive and spread COVID-19 to at least 13 others — the regular ICE Air flights from San Diego and the Phoenix-area to Guadalajara appear to have halted since March 16. Those flights had formed part of an agreement between Mexico and the US to deport individuals to the interior of the country.

In just the last week, Swift Air has flown 11 likely deportation flights to seven different countries: Brazil, Haiti, the Dominican Republic, and Jamaica, as well as Central American favorites Guatemala, Honduras, and El Salvador.

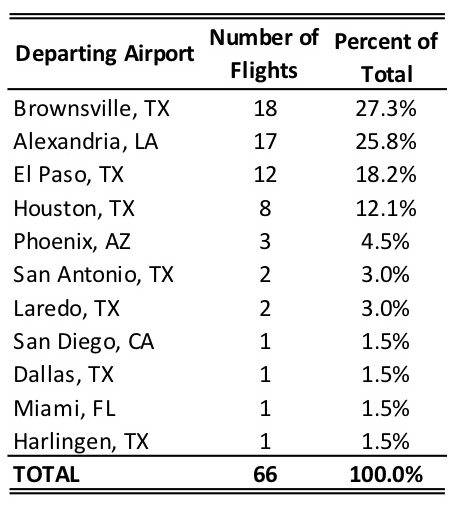

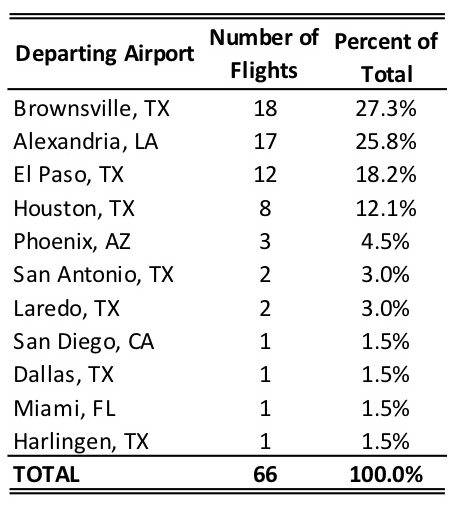

The majority of the flights analyzed departed from two airports well-known to be ICE deportation locations: Brownsville, Texas and Alexandria, Louisiana. The Alexandria ICE staging facility, which is run by the private prison company GEO Group, has been particularly hard hit by COVID-19, with at least 11 employees testing positive. The plane that brought an estimated 40 confirmed COVID-19 cases to Guatemala last week departed from the Alexandria airport.

Overall, the Guatemalan government has estimated that 20 percent of the country’s confirmed COVID-19 cases are recently returned immigrants.

Table 2. Likely ICE Deportation Flights After March 13, by Departure Airport

Source: Flight Aware, author’s calculation.

Note: The total number of flights seen here does not match the overall number of flights after March 13 because some trips included multiple stops.

Despite the obvious public health concerns, ICE has so far refused to test detainees prior to deportation — though officials have recently indicated they would begin at least partial testing. The Washington Post reported that ICE “is unlikely to administer tests to every deportee unless foreign governments make that a condition for taking people back.”

The reality is that, in the shady world of ICE Air, the public has little clue as to the extent of the transportation of detainees — not just internationally but domestically. ProPublica reported last month that one detainee was flown across the United States nine times in a matter of 10 days. That case was not unique. Public health experts have warned that ICE detention centers pose a serious health risk to those held inside — as well as to employees and surrounding communities. Because detainees are often flown across the country and are held in closely confined spaces, it is virtually impossible to adequately isolate those who have contracted COVID-19 or to ensure that those deported have not been exposed to COVID-19.

Some US municipalities have taken it upon themselves to push back on ICE Air’s deportation racket. In 2019, King County in Washington banned ICE from conducting deportation flights from its local airport — though the Trump administration has since sued the local authorities. But it appears some communities are attempting to follow suit amid the global pandemic. Local leaders in El Paso recently raised concerns over continued deportation flights after an ICE flight carrying a passenger with a confirmed case of COVID-19 passed through the municipality-run airport.

But ICE Air is big business; from 2010 to 2017, ICE spent an estimated $1 billion on the program. In 2017, the Trump administration awarded a new primary contract to Classic Air Charters — the same company used as part of the CIA’s black site rendition program during the Bush administration. The ICE contract has an expected value of more than $300 million. Already in 2020, ICE has disbursed more than $90 million under the contract. Because both Swift Air and Western Atlantic operate as subcontractors, there is no public information on the value of their contracts with the federal government. The New York Times reported in 2017 that Swift took in an estimated $15 million per year from the government. ICE Air contractors charge about $8,000 per flight hour — regardless of the number of passengers. In 2019, iAero Group and Blackstone — one of world’s largest private equity firms — purchased Swift Air, though it continues to operate under the same name.

Over the last 12 weeks, it appears that ICE has used 22 unique charter planes for 232 likely deportation flights. Of those planes, 15 participated in confirmed ICE Air deportation flights between October 2018 and May 2019, the most recent data compiled by UWCHR.

Previously, flight tracking software allowed users to see all flights with the call sign “RPN” for “repatriation.” However, it appears that service is no longer accessible and that current ICE Air flights are no longer using the RPN designation. A full list of likely deportation flights since the beginning of February is available here (the data will be updated regularly). The data includes the tag numbers of the 22 planes identified in an effort to promote public awareness around ongoing deportation flights.

Of course, it remains possible that some of these flights reflect regular charter services and not ICE deportation flights. Last week, citing a local airport official, the Miami Herald reported two Swift Air flights were deportation flights to Honduras and Brazil. The official, however, later said he had been “mistaken” and told the Herald the planes had been chartered by Royal Caribbean. If you have information that one of the listed flights was not in fact an ICE Air deportation flight, or if there is a known deportation flight missing from the list, please contact the author ([email protected]).

[Data update: Since the data was collected for this analysis, two additional flights have been added to the likely ICE deportation flight database. These flights help illustrate how the data may be helpful in identifying deportation flights moving forward. On Monday, April 27, a Swift Air flight departed Houston, Texas headed to San Pedro Sula, Honduras. This is the fifth consecutive Monday in which a Swift Air flight traveled to San Pedro Sula. On Tuesday, April 28, a Swift Air flight departed Houston, Texas headed toward San Salvador, El Salvador. This is the sixth consecutive Tuesday a Swift Air plane has flown to San Salvador. On the other hand, on April 27, a Swift Air plane flew to Guatemala but that trip used a flight number not previously associated with known deportation flights and is excluded from the dataset.]

Maps and visualizations created by Kevin Cashman.

There were 232 likely ICE Air deportation flights to Latin America and Caribbean countries between February 3, 2020 and April 24, 2020, CEPR analysis shows.

In 2019, Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) deported 267,258 individuals — 96 percent of whom were from the Latin America and Caribbean region. Though much of the media focus has been on Mexico (49.7 percent of the total) and the Central American nations of Guatemala, Honduras, and El Salvador (together 45.1 percent of the total), ICE deported at least one person to every country in the LAC region in 2019. Ten countries in the region accepted regular deportation flights conducted by ICE’s air operations — known as “ICE Air” — last year.

While the vast majority of deportations to Mexico take place over land, ICE Air flies tens of thousands of people across the country and across the world each year. Amid the global pandemic, which has led to countries shutting down air travel and closing borders, ICE Air continues to deport thousands of immigrants held in detention centers throughout the United States. Those facilities themselves have become hotspots of COVID-19 outbreaks, meaning the US is now exporting the virus to countries throughout the region.

Despite the prevalence of ICE Air deportation flights, and the grave risk to public health that their continuation during the global pandemic presents, little is known about their frequency and destinations. However, a new analysis of flight tracker data sheds some much-needed light on the scope of ICE Air flights and the extent to which countries in Latin America and the Caribbean are affected by continued deportations. Since the Trump administration declared a national emergency on March 13, one ICE Air contractor has flown at least 72 likely deportation flights to 11 Latin America and Caribbean nations — including to Brazil and Ecuador, which are suffering the region’s worst outbreaks of COVID-19, and which have both experienced an increase in deportation flights under the Trump administration.

From March 15 to April 24, ICE Air appears to have made 21 deportation flights to Guatemala; 18 to Honduras; 12 to El Salvador; six to Brazil; three each to Nicaragua, Ecuador, Haiti, and the Dominican Republic; and one each to Colombia and Jamaica. All likely ICE Air deportation flights since February can be seen in the interactive map below.

In 2019, researchers from the University of Washington Center for Human Rights (UWCHR) obtained ICE flight records from 2010 to 2018 following a Freedom of Information Act request. The UWCHR analysis provided the most complete analysis of the extent of ICE Air operations, and their full dataset is available here. Their report also revealed that two private charter companies — Swift Air and Western Atlantic Airlines — conducted the majority of ICE Air deportation flights as subcontractors.

The data analyzed in this post was collected from Flight Aware, a public flight tracker database. Because both Swift and Western perform regular charter services, not all of their flights are part of ICE’s deportation system. However, the flights included in this analysis match known deportation trips, depart from airports known to be used for deportation flights, and follow routes known to be associated with the transport of ICE detainees. While it is possible some of the flights included here were not deportations, it is more likely that this data represents an underestimate of the extent of ICE Air’s operations. ICE is also known to use commercial airlines for deportations and it remains possible that additional charter companies are contracted by ICE. In fiscal year 2017 more than 85 percent of ICE Air deportations were conducted through charter services, according to the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) Inspector General.

In the first three months of 2020, ICE deported an average of 20,833 individuals each month — on pace for a similar annual number as in 2019. In contrast, the Washington Post reported that in the first 11 days of April 2020, ICE deported 2,985 people — less than half that rate. Indeed, the flight tracking data analyzed here shows a decrease in deportation flights beginning around March 13 — as can be seen in the table below.

Table 1. ICE Air Likely Deportation Flights, by Week

Source: Flight Aware, author’s calculation.

The drop visible in the table above appears to result from the stoppage of Western Atlantic’s international charter flights on March 13 — when the US declared a national emergency. ICE Air’s other subcontractor, Swift Air, has continued flying. Despite growing restrictions on international air travel, Swift had almost exactly as many flights from the US to Latin America and the Caribbean in March as it did in February — though that number has decreased some in April. (In recent months, Swift-owned airplanes have made trips to an additional number of countries in the region, including Cuba, Suriname, Peru, Bolivia, Trinidad and Tobago, Aruba, Belize, and Grenada; however those flights did not match up with known deportation flights and have been excluded from the analysis.)

Though much attention has been paid to recent deportation flights to Guatemala and Haiti — both countries have reported confirmed COVID-19 cases among those deported — the data reveal that many other countries are likely experiencing the same phenomenon.

In 2019, the Trump administration began ICE Air deportations to Brazil, which had previously blocked such flights. The United States relies on foreign governments to approve deportation flights, and under the leadership of Trump-ally Jair Bolsonaro, Brazil acquiesced. Flight data indicate that those flights have continued during the pandemic. Since March 13, there have been six flights conducted by Swift Air to Belo Horizonte, Brazil — the destination of previously reported deportation flights. Brazil is currently experiencing the largest outbreak of COVID-19 in the region.

Some of the Swift Air flights to Brazil have first made a stop in Ecuador’s port city Guayaquil — home to perhaps the deadliest outbreak of COVID-19 in the world. Deportations to Ecuador increased by 78 percent in 2019 compared to the year prior as, similar to the Brazilian government, Ecuador has sought to bolster relations with the Trump administration. As can be seen in the table above, likely deportation flights to Ecuador have decreased since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. However, there have still been three since March 13 — including an April 17 flight to Quito that contained at least 70 individuals, according to immigration attorneys.

Interestingly, while deportations to Mexico have continued — one recent deportee has since tested positive and spread COVID-19 to at least 13 others — the regular ICE Air flights from San Diego and the Phoenix-area to Guadalajara appear to have halted since March 16. Those flights had formed part of an agreement between Mexico and the US to deport individuals to the interior of the country.

In just the last week, Swift Air has flown 11 likely deportation flights to seven different countries: Brazil, Haiti, the Dominican Republic, and Jamaica, as well as Central American favorites Guatemala, Honduras, and El Salvador.

The majority of the flights analyzed departed from two airports well-known to be ICE deportation locations: Brownsville, Texas and Alexandria, Louisiana. The Alexandria ICE staging facility, which is run by the private prison company GEO Group, has been particularly hard hit by COVID-19, with at least 11 employees testing positive. The plane that brought an estimated 40 confirmed COVID-19 cases to Guatemala last week departed from the Alexandria airport.

Overall, the Guatemalan government has estimated that 20 percent of the country’s confirmed COVID-19 cases are recently returned immigrants.

Table 2. Likely ICE Deportation Flights After March 13, by Departure Airport

Source: Flight Aware, author’s calculation.

Note: The total number of flights seen here does not match the overall number of flights after March 13 because some trips included multiple stops.

Despite the obvious public health concerns, ICE has so far refused to test detainees prior to deportation — though officials have recently indicated they would begin at least partial testing. The Washington Post reported that ICE “is unlikely to administer tests to every deportee unless foreign governments make that a condition for taking people back.”

The reality is that, in the shady world of ICE Air, the public has little clue as to the extent of the transportation of detainees — not just internationally but domestically. ProPublica reported last month that one detainee was flown across the United States nine times in a matter of 10 days. That case was not unique. Public health experts have warned that ICE detention centers pose a serious health risk to those held inside — as well as to employees and surrounding communities. Because detainees are often flown across the country and are held in closely confined spaces, it is virtually impossible to adequately isolate those who have contracted COVID-19 or to ensure that those deported have not been exposed to COVID-19.

Some US municipalities have taken it upon themselves to push back on ICE Air’s deportation racket. In 2019, King County in Washington banned ICE from conducting deportation flights from its local airport — though the Trump administration has since sued the local authorities. But it appears some communities are attempting to follow suit amid the global pandemic. Local leaders in El Paso recently raised concerns over continued deportation flights after an ICE flight carrying a passenger with a confirmed case of COVID-19 passed through the municipality-run airport.

But ICE Air is big business; from 2010 to 2017, ICE spent an estimated $1 billion on the program. In 2017, the Trump administration awarded a new primary contract to Classic Air Charters — the same company used as part of the CIA’s black site rendition program during the Bush administration. The ICE contract has an expected value of more than $300 million. Already in 2020, ICE has disbursed more than $90 million under the contract. Because both Swift Air and Western Atlantic operate as subcontractors, there is no public information on the value of their contracts with the federal government. The New York Times reported in 2017 that Swift took in an estimated $15 million per year from the government. ICE Air contractors charge about $8,000 per flight hour — regardless of the number of passengers. In 2019, iAero Group and Blackstone — one of world’s largest private equity firms — purchased Swift Air, though it continues to operate under the same name.

Over the last 12 weeks, it appears that ICE has used 22 unique charter planes for 232 likely deportation flights. Of those planes, 15 participated in confirmed ICE Air deportation flights between October 2018 and May 2019, the most recent data compiled by UWCHR.

Previously, flight tracking software allowed users to see all flights with the call sign “RPN” for “repatriation.” However, it appears that service is no longer accessible and that current ICE Air flights are no longer using the RPN designation. A full list of likely deportation flights since the beginning of February is available here (the data will be updated regularly). The data includes the tag numbers of the 22 planes identified in an effort to promote public awareness around ongoing deportation flights.

Of course, it remains possible that some of these flights reflect regular charter services and not ICE deportation flights. Last week, citing a local airport official, the Miami Herald reported two Swift Air flights were deportation flights to Honduras and Brazil. The official, however, later said he had been “mistaken” and told the Herald the planes had been chartered by Royal Caribbean. If you have information that one of the listed flights was not in fact an ICE Air deportation flight, or if there is a known deportation flight missing from the list, please contact the author ([email protected]).

[Data update: Since the data was collected for this analysis, two additional flights have been added to the likely ICE deportation flight database. These flights help illustrate how the data may be helpful in identifying deportation flights moving forward. On Monday, April 27, a Swift Air flight departed Houston, Texas headed to San Pedro Sula, Honduras. This is the fifth consecutive Monday in which a Swift Air flight traveled to San Pedro Sula. On Tuesday, April 28, a Swift Air flight departed Houston, Texas headed toward San Salvador, El Salvador. This is the sixth consecutive Tuesday a Swift Air plane has flown to San Salvador. On the other hand, on April 27, a Swift Air plane flew to Guatemala but that trip used a flight number not previously associated with known deportation flights and is excluded from the dataset.]

Maps and visualizations created by Kevin Cashman.

• COVID-19CoronavirusLatin America and the CaribbeanAmérica Latina y el CaribeWorldEl Mundo

As the COVID-19 pandemic continues to expand around the world, Latin America is expected to become one of the hardest-hit regions. One of the biggest obstacles countries face in responding to the pandemic is that, according to the International Labor Organization (ILO), about 40 percent of all employment in the Americas in 2019 was informal. Many of these workers depend on day-to-day activities just to survive, and complying with stay-at-home orders is often a life-or-death decision. This indicates a worrying outlook for street vendors, domestic workers, and even small business owners. The ILO notes that there has been growth in the informal sector in the last few years, rendering the region even more susceptible to large economic damage from the COVID-19 pandemic. The International Monetary Fund is forecasting a 5.2 percentage point fall in the region’s GDP in 2020 as a result of the ongoing crisis.

Government responses must be universal

While most governments in the region have enforced some level of stay-at-home order, these policies highlight the fragile nature of many lives in Latin America and how they will be strained further due to the novel coronavirus pandemic. The prevalence of informal employment points to the need for governments to enact universal policies that ensure access to assistance and health care for all those affected.

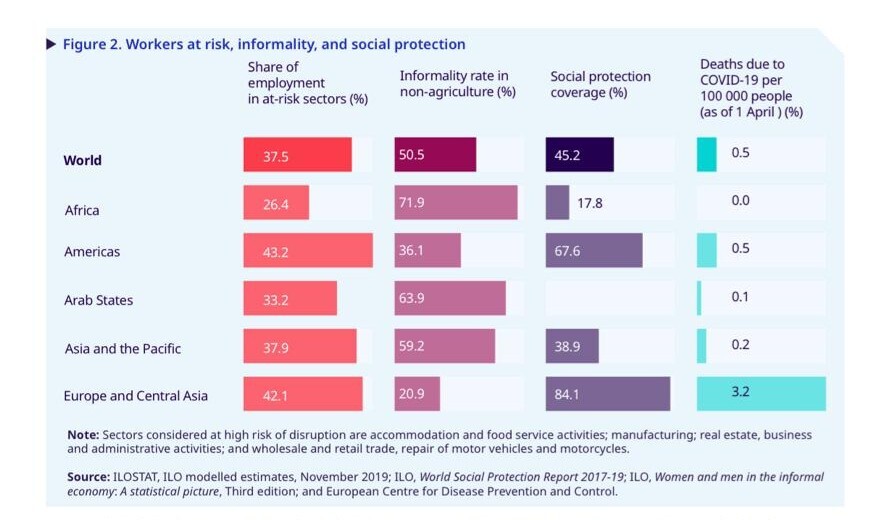

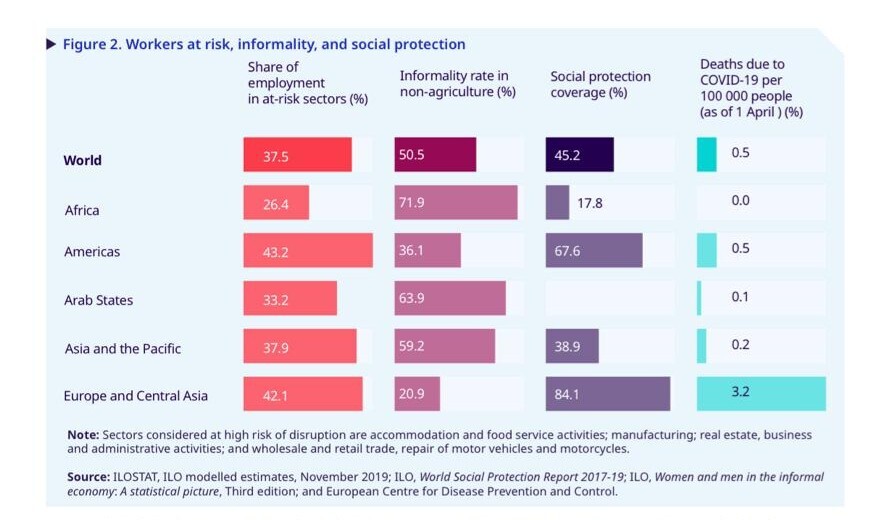

Those in the informal economy are at particular risk during the pandemic. As can be seen in the figure below, the ILO notes that the Americas has the highest percentage of workers employed in “at-risk” sectors, while more than 30 percent of Latin Americans are not covered by governments’ social protection measures.

Because of the high rate of unregistered businesses and informal workers, only a small percentage of aid aimed at formal sectors is likely to reach these employers, their workers, and their employees’ families. In responding to the pandemic, governments must design policy responses with informality at the forefront. Food distributions, cash payouts, and access to public services must be accessible to all — even those not formally employed. Some governments have acknowledged this reality. The Colombian and Brazilian governments have both proposed $40 monthly payouts, though this is unlikely to adequately support informal workers throughout the crisis. Venezuelan migrants in Colombia are undoubtedly among the hardest hit during this outbreak. 60% of the nearly 1.8 millions Venezuelans in Colombia don’t have regular status. This suggests that a staggering number of Venezuelan migrants work in the informal sector and will need to be taken into consideration when drafting more inclusive policies.

An increase in inequality calls for formalizing more workers

Unfortunately, with an expected deep economic downturn, Latin America risks seeing a steep increase in inequality. According to a report published by Oxfam, there are currently 162 million people living on $5.50 a day in Latin America and the Caribbean, and even a 5 percent contraction in income means 2.6 million people will fall under the poverty line. In its report Oxfam predicts in the most extreme case of a 20 percent contraction, there could be an increase in the number of those in poverty ranging from 13.1 million to 54.3 million. Although some of these people might work in the formal economy (e.g., for factories), the reality is that the crisis could push many more into the informal economy, exacerbating inequality in the region.

Projected Effects of Drops in Income to the Poor in Latin America and the Carribean

(the term ¨hit¨ designates a contraction in income)

|

Number of Poor (million) |

Additional Poor (million) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Aggregated |

Status quo |

5% hit |

10% hit |

20% hit |

5% hit |

10% hit |

20% hit |

|

Under $1.90 a Day |

25.3 |

27.9 |

30.8 |

38.5 |

2.6 |

5.5 |

13.1 |

|

Under $3.20 a Day |

66.4 |

72.8 |

80.2 |

98.6 |

6.4 |

13.8 |

32.1 |

|

Under $5.50 a Day |

162.0 |

174.6 |

187.8 |

216.3 |

12.5 |

25.8 |

54.3 |

|

Source: Oxfam |

|||||||

ILO Director-General Guy Ryder stated that after this crisis unfolds, new systems must be “safer, fairer and more sustainable.” This must include a plan to make formal economies more inclusive and social protections more extensive. Informal labor markets show the unfortunate reality of many in Latin America, and the current crisis should be an opportunity for government officials to recognize the importance of formalizing these workers in the economy. Decision-makers must however, do so in a way that will not expand pre-existing inequalities but rather offer a platform to reduce the economic gap in the region.

As the COVID-19 pandemic continues to expand around the world, Latin America is expected to become one of the hardest-hit regions. One of the biggest obstacles countries face in responding to the pandemic is that, according to the International Labor Organization (ILO), about 40 percent of all employment in the Americas in 2019 was informal. Many of these workers depend on day-to-day activities just to survive, and complying with stay-at-home orders is often a life-or-death decision. This indicates a worrying outlook for street vendors, domestic workers, and even small business owners. The ILO notes that there has been growth in the informal sector in the last few years, rendering the region even more susceptible to large economic damage from the COVID-19 pandemic. The International Monetary Fund is forecasting a 5.2 percentage point fall in the region’s GDP in 2020 as a result of the ongoing crisis.

Government responses must be universal

While most governments in the region have enforced some level of stay-at-home order, these policies highlight the fragile nature of many lives in Latin America and how they will be strained further due to the novel coronavirus pandemic. The prevalence of informal employment points to the need for governments to enact universal policies that ensure access to assistance and health care for all those affected.

Those in the informal economy are at particular risk during the pandemic. As can be seen in the figure below, the ILO notes that the Americas has the highest percentage of workers employed in “at-risk” sectors, while more than 30 percent of Latin Americans are not covered by governments’ social protection measures.

Because of the high rate of unregistered businesses and informal workers, only a small percentage of aid aimed at formal sectors is likely to reach these employers, their workers, and their employees’ families. In responding to the pandemic, governments must design policy responses with informality at the forefront. Food distributions, cash payouts, and access to public services must be accessible to all — even those not formally employed. Some governments have acknowledged this reality. The Colombian and Brazilian governments have both proposed $40 monthly payouts, though this is unlikely to adequately support informal workers throughout the crisis. Venezuelan migrants in Colombia are undoubtedly among the hardest hit during this outbreak. 60% of the nearly 1.8 millions Venezuelans in Colombia don’t have regular status. This suggests that a staggering number of Venezuelan migrants work in the informal sector and will need to be taken into consideration when drafting more inclusive policies.

An increase in inequality calls for formalizing more workers

Unfortunately, with an expected deep economic downturn, Latin America risks seeing a steep increase in inequality. According to a report published by Oxfam, there are currently 162 million people living on $5.50 a day in Latin America and the Caribbean, and even a 5 percent contraction in income means 2.6 million people will fall under the poverty line. In its report Oxfam predicts in the most extreme case of a 20 percent contraction, there could be an increase in the number of those in poverty ranging from 13.1 million to 54.3 million. Although some of these people might work in the formal economy (e.g., for factories), the reality is that the crisis could push many more into the informal economy, exacerbating inequality in the region.

Projected Effects of Drops in Income to the Poor in Latin America and the Carribean

(the term ¨hit¨ designates a contraction in income)

|

Number of Poor (million) |

Additional Poor (million) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Aggregated |

Status quo |

5% hit |

10% hit |

20% hit |

5% hit |

10% hit |

20% hit |

|

Under $1.90 a Day |

25.3 |

27.9 |

30.8 |

38.5 |

2.6 |

5.5 |

13.1 |

|

Under $3.20 a Day |

66.4 |

72.8 |

80.2 |

98.6 |

6.4 |

13.8 |

32.1 |

|

Under $5.50 a Day |

162.0 |

174.6 |

187.8 |

216.3 |

12.5 |

25.8 |

54.3 |

|

Source: Oxfam |

|||||||

ILO Director-General Guy Ryder stated that after this crisis unfolds, new systems must be “safer, fairer and more sustainable.” This must include a plan to make formal economies more inclusive and social protections more extensive. Informal labor markets show the unfortunate reality of many in Latin America, and the current crisis should be an opportunity for government officials to recognize the importance of formalizing these workers in the economy. Decision-makers must however, do so in a way that will not expand pre-existing inequalities but rather offer a platform to reduce the economic gap in the region.

• COVID-19CoronavirusLatin America and the CaribbeanAmérica Latina y el Caribe

• COVID-19CoronavirusIMFFondo Monetario InternacionalSpecial Drawing RightsWorldEl Mundo

On April 13, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) announced that it would suspend debt servicing requirements for 25 lower-income countries in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. The program, an expansion of the Catastrophe Containment and Relief Trust (CCRT), would provide “grants to our poorest and most vulnerable members to cover their IMF debt obligations for an initial phase over the next six months,” IMF managing director Kristalina Georgieva said.

Advocates of debt cancellation and relief, such as the Jubilee Debt Campaign, have commended the effort as a necessary first step in allowing poorer countries to invest in public health responses. Jubilee research revealed that, in 2019, 64 countries spent more on debt servicing than on public health.

While the IMF’s debt pause is indeed a welcome step, the French finance minister, Bruno Le Maire, told the press that the IMF is thus far resistant to a large allocation of the Fund’s reserve currency, Special Drawing Rights (SDRs). An SDR allocation would provide needed resources for developing economies, but could also free up additional resources to expand debt relief operations. Opposition, Le Maire said, is coming from the United States — which remains the IMF’s largest voting member and maintains virtual veto power over IMF activities. Bloomberg reports:

“The U.S. response for now is negative,” Le Maire told reporters on Tuesday ahead of a call with Group of Seven finance chiefs Tuesday and virtual meetings of the IMF and World Bank this week. “But we continue to think it is a response that is not costly for IMF members and very effective for developing countries.”

While no agreement is likely on Wednesday, France will keep pushing because the measure is more monetary than fiscal so would be less of a burden on budgets, according to a finance ministry official, who declined to be identified in line with government policy.

…

More SDRs could help ensure emerging markets avoid a cash crunch as they deal with the health crisis, economic stagnation and capital outflows. The IMF’s executive board on Monday approved debt service relief for 25 countries for six months via its Catastrophe Containment and Relief Trust.

In a recent report, Mark Sobel, the U.S.’s former executive director at the IMF, has said there are “better and more effective solutions” for the IMF to embrace than seeking more SDRs, such as offering short-term loans of dollars.

The six-month debt suspension to the IMF is projected to save the 25 affected countries a total of $225 million. In no case would the debt relief amount to more than 0.5 percent of a country’s GDP. With global growth expected to nose-dive and capital outflows from emerging markets already reaching record levels, debt relief alone is inadequate. The IMF’s Georgieva has estimated developing country finance needs at $2.5 trillion. UNCTAD has called for $2.5 trillion in support. CEPR economists Mark Weisbrot and Andrés Arauz have previously called for a 3 trillion SDR allocation. The Financial Times editorial board called for an allocation of 1.37 trillion SDRs. However, even a much lower allocation of $500 billion would deliver more than $7 billion in needed reserve assets to the 25 countries that received debt relief.

Some have raised concerns over an SDR allocation by noting that more than half of the resources would go toward developed countries that are able to access external credit lines — such as those offered by the Fed. But an SDR allocation, if handled appropriately, could provide an invaluable buffer to developing countries’ reserves, while also allowing the vast expansion of the IMF’s debt relief trust, in addition to other bilateral or regional arrangements. The IMF could allow developed countries — or those who do not need an infusion of SDRs — to donate their allocation to a centralized IMF trust. That trust, with its capitalization greatly enhanced, would be able to greatly expand debt relief operations throughout the world, beyond the initial 25 countries, and beyond the next six months.

Though the US has remained steadfast in its opposition to an SDR allocation, the policy has received widespread support — even from financial sector actors. As Bloomberg reported:

“Some major members remain unconvinced for now, but ultimately concerns about the negative effects of money creation at the IMF would be the same as on the national level where central banks have been rapidly expanding money supply,” Bank of America Corp. analysts said in a report on Tuesday. “In a world of massive demand shortage and deleveraging, inflation seems a rather unlikely concern.”

The costs are low, but the upside to the global economy — particularly to those countries most vulnerable — could be tremendous, not just in terms of stabilizing reserves, but also, if done well, in offering unprecedented debt relief amid the ongoing pandemic.

On April 13, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) announced that it would suspend debt servicing requirements for 25 lower-income countries in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. The program, an expansion of the Catastrophe Containment and Relief Trust (CCRT), would provide “grants to our poorest and most vulnerable members to cover their IMF debt obligations for an initial phase over the next six months,” IMF managing director Kristalina Georgieva said.

Advocates of debt cancellation and relief, such as the Jubilee Debt Campaign, have commended the effort as a necessary first step in allowing poorer countries to invest in public health responses. Jubilee research revealed that, in 2019, 64 countries spent more on debt servicing than on public health.

While the IMF’s debt pause is indeed a welcome step, the French finance minister, Bruno Le Maire, told the press that the IMF is thus far resistant to a large allocation of the Fund’s reserve currency, Special Drawing Rights (SDRs). An SDR allocation would provide needed resources for developing economies, but could also free up additional resources to expand debt relief operations. Opposition, Le Maire said, is coming from the United States — which remains the IMF’s largest voting member and maintains virtual veto power over IMF activities. Bloomberg reports:

“The U.S. response for now is negative,” Le Maire told reporters on Tuesday ahead of a call with Group of Seven finance chiefs Tuesday and virtual meetings of the IMF and World Bank this week. “But we continue to think it is a response that is not costly for IMF members and very effective for developing countries.”

While no agreement is likely on Wednesday, France will keep pushing because the measure is more monetary than fiscal so would be less of a burden on budgets, according to a finance ministry official, who declined to be identified in line with government policy.

…

More SDRs could help ensure emerging markets avoid a cash crunch as they deal with the health crisis, economic stagnation and capital outflows. The IMF’s executive board on Monday approved debt service relief for 25 countries for six months via its Catastrophe Containment and Relief Trust.

In a recent report, Mark Sobel, the U.S.’s former executive director at the IMF, has said there are “better and more effective solutions” for the IMF to embrace than seeking more SDRs, such as offering short-term loans of dollars.

The six-month debt suspension to the IMF is projected to save the 25 affected countries a total of $225 million. In no case would the debt relief amount to more than 0.5 percent of a country’s GDP. With global growth expected to nose-dive and capital outflows from emerging markets already reaching record levels, debt relief alone is inadequate. The IMF’s Georgieva has estimated developing country finance needs at $2.5 trillion. UNCTAD has called for $2.5 trillion in support. CEPR economists Mark Weisbrot and Andrés Arauz have previously called for a 3 trillion SDR allocation. The Financial Times editorial board called for an allocation of 1.37 trillion SDRs. However, even a much lower allocation of $500 billion would deliver more than $7 billion in needed reserve assets to the 25 countries that received debt relief.

Some have raised concerns over an SDR allocation by noting that more than half of the resources would go toward developed countries that are able to access external credit lines — such as those offered by the Fed. But an SDR allocation, if handled appropriately, could provide an invaluable buffer to developing countries’ reserves, while also allowing the vast expansion of the IMF’s debt relief trust, in addition to other bilateral or regional arrangements. The IMF could allow developed countries — or those who do not need an infusion of SDRs — to donate their allocation to a centralized IMF trust. That trust, with its capitalization greatly enhanced, would be able to greatly expand debt relief operations throughout the world, beyond the initial 25 countries, and beyond the next six months.

Though the US has remained steadfast in its opposition to an SDR allocation, the policy has received widespread support — even from financial sector actors. As Bloomberg reported:

“Some major members remain unconvinced for now, but ultimately concerns about the negative effects of money creation at the IMF would be the same as on the national level where central banks have been rapidly expanding money supply,” Bank of America Corp. analysts said in a report on Tuesday. “In a world of massive demand shortage and deleveraging, inflation seems a rather unlikely concern.”

The costs are low, but the upside to the global economy — particularly to those countries most vulnerable — could be tremendous, not just in terms of stabilizing reserves, but also, if done well, in offering unprecedented debt relief amid the ongoing pandemic.

• COVID-19CoronavirusLatin America and the CaribbeanAmérica Latina y el CaribeWorldEl Mundo

• BrazilBrasilCOVID-19CoronavirusLatin America and the CaribbeanAmérica Latina y el Caribe

As of noon on April 8th the total number of Covid-19 positive cases reported by Brazil’s health ministry exceeded 14,000 and the number of deaths exceeded 700. This is, by far, the highest number of reported cases in Latin America (though Ecuador has a greater number of reported cases and deaths on a per capita basis). The actual number of cases is likely many times greater, given that the current rate of testing for Covid-19 in Brazil is still very low – 258 per million, compared to 3,159 per million in Chile, 6,423 per million in the U.S. and 10,962 per million in Germany. In São Paulo, Brazil’s biggest city, and the hardest hit urban area in the country, the local health secretariat is reportedly only providing tallies for severe cases of the virus.

Far right Brazilian president Jair Bolsonaro, an admirer and close ally of President Trump, has been seriously downplaying the gravity of the pandemic. He has referred to the virus as a “little flu” and has openly flouted social distancing measures, promoting political rallies in mid March and wading into crowds of supporters. Ironically, prior to the recent rallies, senior members of Bolsonaro’s cabinet tested positive for the virus following an international trip that included a meeting with Trump at Mar-a-Lago. These and other members of the delegation were among the first imported cases of Covid-19 to Brazil (and it is rumored that Bolsonaro himself was infected).

As seems to be the case with his U.S. counterpart and mentor, Bolsonaro’s rejection of experts’ recommendations has a clear motivation: keeping the economy running at all costs. Even before the virus arrived, Brazil’s economy was in sad shape, with no signs of real recovery following a deep recession in 2015-16. Unemployment remained stubbornly high (more than 11.6 percent in February) and economic growth stood at less than one percent during the first year of Bolsonaro’s presidency (as might be expected given the government’s constitutionally-mandated austerity policies). As is the case in most of Latin America (see ECLAC’s grim predictions for the region), business state and local shut-downs and stay-at-home measures designed to save hundreds of thousands of lives are expected to have devastating economic consequences. Brazil’s biggest bank, Itaú, forecasts as much as 6.4% negative economic growth for 2020 alone if virus containment measures are maintained for an extended period of time.

In response to these and other dire predictions, Brazil’s lower house has passed a “war budget” amendment to the constitution, which – if approved by 3/5 of the Senate – will ease current draconian budget constraints and allow the state to engage in significant deficit spending to try to address the country’s looming health and economic emergencies. Meanwhile, many of Brazil’s state governors have ordered non-essential businesses to close and have supported social distancing measures. In response, Bolsonaro has engaged in heated clashes with governors and threatened to issue a decree forcing businesses to re-open throughout the country. He has also butted heads with his own health minister, Luis Henrique Mandetta, who has supported strong social distancing protocols, threatening at one point to fire him. Currently Mandetta has the highest ratings of any politician in the country while Bolsonaro’s favorability ratings have been sinking. Millions of people in cities across Brazil have protested Bolsonaro’s dismissive approach with regular panelaços – loud, pot-banging protests staged from residents’ windows and balconies. Brazil’s major leftwing leaders have called for the president’s resignation.

It’s possible that Bolsonaro is making a long-term political calculation, attempting to position himself to better weather the coming economic tsunami by blaming others for taking lifesaving measures that shut down much of the economy. Here again, his behavior bears similarities with that of the occupant of the White House.

Regardless of what social distancing steps are taken throughout Brazil, many observers believe that the pandemic will exact a particularly terrible human and economic toll in the country’s poor favelas, where around 11 million people live. Historically neglected by public authorities (apart from police agents engaged in increasingly widespread extrajudicial killings targeting Black youth), favela communities have extremely limited access to healthcare resources and water and sanitation infrastructures. As Brazilian-Colombian researcher Nicole Froio explains in NACLA, many favela residents are simply unable to wash their hands regularly or practice social distancing measures in houses where large families share tiny living spaces. Given the lack of effective support from the state, favela communities in Río de Janeiro and São Paulo are pooling scant resources to hire round-the-clock medical support.

Brazil’s rural indigenous communities are also particularly vulnerable, given the fact that they are often located far away from hospitals able to treat infected patients with acute symptoms. Ironically, the first indigenous Brazilian to test positive for Covid-19 is a healthcare worker who was in contact with an infected medical doctor who was visiting a remote Kokoma community. Researchers fear that the virus could wreak enormous destruction and havoc in communities, especially as those at highest risk – the elderly – are typically the pillars of social order and transmitters of traditional knowledge. In response to the pandemic, many indigenous peoples are likely to disperse into small groups, according to Dr. Sofia Mendonça, a researcher at the Federal University of São Paulo. Amnesty International reports that some communities are blocking roads and going into voluntary isolation to keep the pandemic at bay.

Amnesty notes that Brazil’s indigenous communities are facing two sorts of attacks now. Alongside the threat of Covid-19 infections, grileiros – those that illegally appropriate land – are taking advantage of the pandemic, and the fact that indigenous communities are prevented from effectively patrolling their territories, to step up the use of indigenous lands for illegal logging, agriculture and mining enterprises. Government protection of indigenous lands has already been severely weakened under Bolsonaro – who has sought to open up indigenous lands for outside exploitation – and indigenous leaders who resist land invaders are being threatened and killed at an increasing rate. On March 31st, Zezico Rodrigues Guajajara, a well-known Guajajara leader and opponent of illegal logging in Araribóia indigenous lands, was assassinated. It was the fifth murder of a Guajajara land rights advocate so far this year, according to Amazon Watch.

As of noon on April 8th the total number of Covid-19 positive cases reported by Brazil’s health ministry exceeded 14,000 and the number of deaths exceeded 700. This is, by far, the highest number of reported cases in Latin America (though Ecuador has a greater number of reported cases and deaths on a per capita basis). The actual number of cases is likely many times greater, given that the current rate of testing for Covid-19 in Brazil is still very low – 258 per million, compared to 3,159 per million in Chile, 6,423 per million in the U.S. and 10,962 per million in Germany. In São Paulo, Brazil’s biggest city, and the hardest hit urban area in the country, the local health secretariat is reportedly only providing tallies for severe cases of the virus.

Far right Brazilian president Jair Bolsonaro, an admirer and close ally of President Trump, has been seriously downplaying the gravity of the pandemic. He has referred to the virus as a “little flu” and has openly flouted social distancing measures, promoting political rallies in mid March and wading into crowds of supporters. Ironically, prior to the recent rallies, senior members of Bolsonaro’s cabinet tested positive for the virus following an international trip that included a meeting with Trump at Mar-a-Lago. These and other members of the delegation were among the first imported cases of Covid-19 to Brazil (and it is rumored that Bolsonaro himself was infected).

As seems to be the case with his U.S. counterpart and mentor, Bolsonaro’s rejection of experts’ recommendations has a clear motivation: keeping the economy running at all costs. Even before the virus arrived, Brazil’s economy was in sad shape, with no signs of real recovery following a deep recession in 2015-16. Unemployment remained stubbornly high (more than 11.6 percent in February) and economic growth stood at less than one percent during the first year of Bolsonaro’s presidency (as might be expected given the government’s constitutionally-mandated austerity policies). As is the case in most of Latin America (see ECLAC’s grim predictions for the region), business state and local shut-downs and stay-at-home measures designed to save hundreds of thousands of lives are expected to have devastating economic consequences. Brazil’s biggest bank, Itaú, forecasts as much as 6.4% negative economic growth for 2020 alone if virus containment measures are maintained for an extended period of time.

In response to these and other dire predictions, Brazil’s lower house has passed a “war budget” amendment to the constitution, which – if approved by 3/5 of the Senate – will ease current draconian budget constraints and allow the state to engage in significant deficit spending to try to address the country’s looming health and economic emergencies. Meanwhile, many of Brazil’s state governors have ordered non-essential businesses to close and have supported social distancing measures. In response, Bolsonaro has engaged in heated clashes with governors and threatened to issue a decree forcing businesses to re-open throughout the country. He has also butted heads with his own health minister, Luis Henrique Mandetta, who has supported strong social distancing protocols, threatening at one point to fire him. Currently Mandetta has the highest ratings of any politician in the country while Bolsonaro’s favorability ratings have been sinking. Millions of people in cities across Brazil have protested Bolsonaro’s dismissive approach with regular panelaços – loud, pot-banging protests staged from residents’ windows and balconies. Brazil’s major leftwing leaders have called for the president’s resignation.

It’s possible that Bolsonaro is making a long-term political calculation, attempting to position himself to better weather the coming economic tsunami by blaming others for taking lifesaving measures that shut down much of the economy. Here again, his behavior bears similarities with that of the occupant of the White House.

Regardless of what social distancing steps are taken throughout Brazil, many observers believe that the pandemic will exact a particularly terrible human and economic toll in the country’s poor favelas, where around 11 million people live. Historically neglected by public authorities (apart from police agents engaged in increasingly widespread extrajudicial killings targeting Black youth), favela communities have extremely limited access to healthcare resources and water and sanitation infrastructures. As Brazilian-Colombian researcher Nicole Froio explains in NACLA, many favela residents are simply unable to wash their hands regularly or practice social distancing measures in houses where large families share tiny living spaces. Given the lack of effective support from the state, favela communities in Río de Janeiro and São Paulo are pooling scant resources to hire round-the-clock medical support.

Brazil’s rural indigenous communities are also particularly vulnerable, given the fact that they are often located far away from hospitals able to treat infected patients with acute symptoms. Ironically, the first indigenous Brazilian to test positive for Covid-19 is a healthcare worker who was in contact with an infected medical doctor who was visiting a remote Kokoma community. Researchers fear that the virus could wreak enormous destruction and havoc in communities, especially as those at highest risk – the elderly – are typically the pillars of social order and transmitters of traditional knowledge. In response to the pandemic, many indigenous peoples are likely to disperse into small groups, according to Dr. Sofia Mendonça, a researcher at the Federal University of São Paulo. Amnesty International reports that some communities are blocking roads and going into voluntary isolation to keep the pandemic at bay.

Amnesty notes that Brazil’s indigenous communities are facing two sorts of attacks now. Alongside the threat of Covid-19 infections, grileiros – those that illegally appropriate land – are taking advantage of the pandemic, and the fact that indigenous communities are prevented from effectively patrolling their territories, to step up the use of indigenous lands for illegal logging, agriculture and mining enterprises. Government protection of indigenous lands has already been severely weakened under Bolsonaro – who has sought to open up indigenous lands for outside exploitation – and indigenous leaders who resist land invaders are being threatened and killed at an increasing rate. On March 31st, Zezico Rodrigues Guajajara, a well-known Guajajara leader and opponent of illegal logging in Araribóia indigenous lands, was assassinated. It was the fifth murder of a Guajajara land rights advocate so far this year, according to Amazon Watch.

• COVID-19CoronavirusEconomic Crisis and RecoveryCrisis económica y recuperaciónIMFFondo Monetario InternacionalLatin America and the CaribbeanAmérica Latina y el CaribeUS Foreign PolicyPolítica exterior de EE. UU.WorldEl Mundo

The Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC) has lowered regional GDP growth projections from positive 1.3 percent to negative 1.8 percent in light of the global COVID-19 pandemic. ECLAC projects that, with such a growth rate, poverty and extreme poverty will increase by 34 million and 23.3 million, respectively. In an op-ed, ECLAC Executive Secretary Alicia Bárcena notes that more than 47 percent of the region’s population does not currently have access to social security, placing the region’s elderly population in a dangerous position.

Bárcena writes:

In the current situation, it cannot be overlooked that massive fiscal stimulus is needed to bolster health services and protect income and jobs, among the numerous challenges at hand. The provision of essential goods (medication, food, energy) cannot be disrupted today, and universal access to testing for COVID-19 must be guaranteed along with medical care for all those who need it. Providing our health care systems with the necessary funds is an unavoidable imperative.

When we talk about massive fiscal stimulus, we are also talking about financing the social protection systems that care for the most vulnerable sectors. We are talking about rolling out non-contributory programs such as direct cash transfers, financing for unemployment insurance, and benefits for the underemployed and self-employed.

Likewise, central banks have to ensure liquidity so the production apparatus can guarantee its continued functioning. These efforts must translate into support for companies with zero-interest loans for paying wages. In addition, companies and households must be aided by the postponement of loan, mortgage and rent payments. Many interventions will be needed to ensure that the chain of payments is not interrupted. Development banks should play a significant role in this.

And, certainly, multilateral financing bodies will have to consider new policies on low-interest loans and offer relief and deferments on current debt servicing to create fiscal space.

Economic distress will come through various channels in the coming months and will not be solely tied to domestic efforts to slow the spread of COVID-19. Remittances, a key source of revenue in many countries, are expected to diminish drastically. The region’s exports are also likely to take a hit as economic growth slows among trading partners. Commodities, which many countries in the region rely upon for foreign exchange, are experiencing significant price declines. ECLAC estimates a possible 10.7 percentage point reduction in the value of the region’s exports this year. The collapse of the tourism industry, especially important in the Caribbean, will also have significant impacts — in some countries calamitous.

Bárcena acknowledged that ECLAC’s projection of -1.8 percent growth in 2020 could turn out to be over-optimistic. Some private estimates already anticipate a much larger shock. Goldman Sachs, for example, projected -3.8 percent growth for Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Ecuador, Mexico, and Peru — which together account for some 89 percent of regional GDP.

S&P Global, although more optimistic than either ECLAC or Goldman in projecting -1.3 percent growth, notes that the risk is very clearly on the downside. As opposed to the six-quarter recession during the Great Recession, however, S&P projects only two quarters of negative regional growth in 2020. The current situation differs in another key regard, according to S&P: regional growth has been slow in previous years, placing economies in an already fragile place before the current slowdown. “Fixed investment has been either declining or slowing across most of the region in recent years,” the ratings agency notes. Further, S&P estimates that the length of the downturn will depend greatly on the public health response of individual countries:

The initial economic policy response to the COVID-19 pandemic in Latin America was similar to other parts of the world: emergency interest rate cuts and programs designed to boost liquidity, followed by fiscal stimulus measures in some countries, most notably in Chile, where a 5% of GDP recovery package was announced. These measures will help curb the fall in demand and reinvigorate the economic recovery once the pandemic wanes. However, the public health policy response, which has diverged across the region, will determine the length of the health crisis, and, as a result, affect the length of the economic crisis.

Unfortunately, few countries in the region are well positioned to robustly respond to the crisis. The Inter-American Development Bank (IDB) points out that 21 of the 26 regional countries borrowing from the IDB reported current account deficits in 2019. With an abrupt halt in countries’ access to foreign capital, many could find themselves in an unsustainable position. Early evidence points to an even greater outflow of capital from the region than during the 2009 financial crisis. Only Brazil and Mexico have capped dollar access via a bilateral swap line with the Federal Reserve to placate this outflow. In contrast to previous periods, however, the COVID-19 pandemic is a truly global problem, meaning that it will be difficult for countries to increase exports to make up for the lack of foreign capital.

Further, traditional stimulus measures are likely to be less impactful than during previous economic downturns given that many businesses will remain closed as part of the public health response to COVID-19. All of this makes a coordinated, international response imperative. The IMF has pledged to increase its lending capacity in response to the crisis, but it is unlikely the fund has the capacity to process loan requests from the more than 80 countries that have already inquired. Further, IMF-supported austerity policies ― such as those in Ecuador and Argentina ― have left those countries in an even worse position to respond to the current situation.

One way for the IMF to respond to the immediate needs of the region ― and developing nations across the globe ― would be with a significant allocation of Special Drawing Rights (SDRs), which function as a reserve currency. In response to the Global Recession in 2009, the IMF increased SDRs by some $250 billion, providing necessary financial lifelines for countries without access to foreign capital. But the current need is far greater. The IMF itself has estimated that developing countries will need some $2.5 trillion to adequately respond to the situation. CEPR economists Mark Weisbrot and Andrés Arauz have called for a 3 trillion SDR allocation (i.e., $4 trillion). The UN is calling for an allocation of 1 trillion SDRs, while some of the largest and most influential economic policy organizations in the US, like the Peterson Institute for International Economics, the Center for Global Development, and the Institute for International Finance support a 500 billion SDR issuance.

What is clear is that the cost of doing nothing is tremendous. The Imperial College of London estimates that, in a worst-case scenario, more than 3 million could die in Latin America and the Caribbean and more than 560 million could be sickened due to COVID-19. The study estimates that, if significant “suppression strategies” are implemented, the death toll could be reduced to 158,000.

But it is important to remember that regardless of the severity in terms of health or the economy, it is likely to be the most vulnerable in the region who will be most affected. As ECLAC notes, the COVID-induced recession will likely push more than 30 million people into poverty throughout the region. Further, many regional economies have expansive informal labor markets that will make it extraordinarily difficult to enforce physical distancing responses to COVID-19. While the wealthy will have resources to stay at home and survive, it will be the most vulnerable, forced to continue working just to live, who will bear the brunt of COVID-19. That will be true in terms of health outcomes as well as economic outcomes, and policy responses should be formulated with that consideration at the forefront.

The Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC) has lowered regional GDP growth projections from positive 1.3 percent to negative 1.8 percent in light of the global COVID-19 pandemic. ECLAC projects that, with such a growth rate, poverty and extreme poverty will increase by 34 million and 23.3 million, respectively. In an op-ed, ECLAC Executive Secretary Alicia Bárcena notes that more than 47 percent of the region’s population does not currently have access to social security, placing the region’s elderly population in a dangerous position.

Bárcena writes:

In the current situation, it cannot be overlooked that massive fiscal stimulus is needed to bolster health services and protect income and jobs, among the numerous challenges at hand. The provision of essential goods (medication, food, energy) cannot be disrupted today, and universal access to testing for COVID-19 must be guaranteed along with medical care for all those who need it. Providing our health care systems with the necessary funds is an unavoidable imperative.

When we talk about massive fiscal stimulus, we are also talking about financing the social protection systems that care for the most vulnerable sectors. We are talking about rolling out non-contributory programs such as direct cash transfers, financing for unemployment insurance, and benefits for the underemployed and self-employed.

Likewise, central banks have to ensure liquidity so the production apparatus can guarantee its continued functioning. These efforts must translate into support for companies with zero-interest loans for paying wages. In addition, companies and households must be aided by the postponement of loan, mortgage and rent payments. Many interventions will be needed to ensure that the chain of payments is not interrupted. Development banks should play a significant role in this.

And, certainly, multilateral financing bodies will have to consider new policies on low-interest loans and offer relief and deferments on current debt servicing to create fiscal space.

Economic distress will come through various channels in the coming months and will not be solely tied to domestic efforts to slow the spread of COVID-19. Remittances, a key source of revenue in many countries, are expected to diminish drastically. The region’s exports are also likely to take a hit as economic growth slows among trading partners. Commodities, which many countries in the region rely upon for foreign exchange, are experiencing significant price declines. ECLAC estimates a possible 10.7 percentage point reduction in the value of the region’s exports this year. The collapse of the tourism industry, especially important in the Caribbean, will also have significant impacts — in some countries calamitous.

Bárcena acknowledged that ECLAC’s projection of -1.8 percent growth in 2020 could turn out to be over-optimistic. Some private estimates already anticipate a much larger shock. Goldman Sachs, for example, projected -3.8 percent growth for Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Ecuador, Mexico, and Peru — which together account for some 89 percent of regional GDP.

S&P Global, although more optimistic than either ECLAC or Goldman in projecting -1.3 percent growth, notes that the risk is very clearly on the downside. As opposed to the six-quarter recession during the Great Recession, however, S&P projects only two quarters of negative regional growth in 2020. The current situation differs in another key regard, according to S&P: regional growth has been slow in previous years, placing economies in an already fragile place before the current slowdown. “Fixed investment has been either declining or slowing across most of the region in recent years,” the ratings agency notes. Further, S&P estimates that the length of the downturn will depend greatly on the public health response of individual countries:

The initial economic policy response to the COVID-19 pandemic in Latin America was similar to other parts of the world: emergency interest rate cuts and programs designed to boost liquidity, followed by fiscal stimulus measures in some countries, most notably in Chile, where a 5% of GDP recovery package was announced. These measures will help curb the fall in demand and reinvigorate the economic recovery once the pandemic wanes. However, the public health policy response, which has diverged across the region, will determine the length of the health crisis, and, as a result, affect the length of the economic crisis.

Unfortunately, few countries in the region are well positioned to robustly respond to the crisis. The Inter-American Development Bank (IDB) points out that 21 of the 26 regional countries borrowing from the IDB reported current account deficits in 2019. With an abrupt halt in countries’ access to foreign capital, many could find themselves in an unsustainable position. Early evidence points to an even greater outflow of capital from the region than during the 2009 financial crisis. Only Brazil and Mexico have capped dollar access via a bilateral swap line with the Federal Reserve to placate this outflow. In contrast to previous periods, however, the COVID-19 pandemic is a truly global problem, meaning that it will be difficult for countries to increase exports to make up for the lack of foreign capital.

Further, traditional stimulus measures are likely to be less impactful than during previous economic downturns given that many businesses will remain closed as part of the public health response to COVID-19. All of this makes a coordinated, international response imperative. The IMF has pledged to increase its lending capacity in response to the crisis, but it is unlikely the fund has the capacity to process loan requests from the more than 80 countries that have already inquired. Further, IMF-supported austerity policies ― such as those in Ecuador and Argentina ― have left those countries in an even worse position to respond to the current situation.

One way for the IMF to respond to the immediate needs of the region ― and developing nations across the globe ― would be with a significant allocation of Special Drawing Rights (SDRs), which function as a reserve currency. In response to the Global Recession in 2009, the IMF increased SDRs by some $250 billion, providing necessary financial lifelines for countries without access to foreign capital. But the current need is far greater. The IMF itself has estimated that developing countries will need some $2.5 trillion to adequately respond to the situation. CEPR economists Mark Weisbrot and Andrés Arauz have called for a 3 trillion SDR allocation (i.e., $4 trillion). The UN is calling for an allocation of 1 trillion SDRs, while some of the largest and most influential economic policy organizations in the US, like the Peterson Institute for International Economics, the Center for Global Development, and the Institute for International Finance support a 500 billion SDR issuance.

What is clear is that the cost of doing nothing is tremendous. The Imperial College of London estimates that, in a worst-case scenario, more than 3 million could die in Latin America and the Caribbean and more than 560 million could be sickened due to COVID-19. The study estimates that, if significant “suppression strategies” are implemented, the death toll could be reduced to 158,000.

But it is important to remember that regardless of the severity in terms of health or the economy, it is likely to be the most vulnerable in the region who will be most affected. As ECLAC notes, the COVID-induced recession will likely push more than 30 million people into poverty throughout the region. Further, many regional economies have expansive informal labor markets that will make it extraordinarily difficult to enforce physical distancing responses to COVID-19. While the wealthy will have resources to stay at home and survive, it will be the most vulnerable, forced to continue working just to live, who will bear the brunt of COVID-19. That will be true in terms of health outcomes as well as economic outcomes, and policy responses should be formulated with that consideration at the forefront.

• BoliviaBoliviaLatin America and the CaribbeanAmérica Latina y el CaribeWorldEl Mundo