• Economic Crisis and RecoveryCrisis económica y recuperaciónUnited StatesEE. UU.

The economy can have a problem of too much demand, leading to serious inflationary pressures. It can also have a problem of too little demand, leading to slow growth and unemployment. But can it have both at the same time?

Apparently, the leading lights in economic policy circles seem to think so. As I noted a few days ago, back in the 1990s and 00s economists were almost universally warning of the bad effects of an aging population. The issue was that we would have too many retirees and too few workers to support them.

This meant a problem of excess demand. Since much of the money to support retirees comes from government programs for the elderly, like Social Security and Medicare, this meant we would see this show up as large government budget deficits, unless we had big tax increases to reduce demand.

In recent years, this view had largely been replaced with concerns over secular stagnation. This is a story where an aging population implies a slow-growing or shrinking labor force. This reduces the need for investment spending. The reduction in investment spending, coupled with other factors increasing saving, gives what Larry Summers referred to as a “savings glut.” This is a story of too little demand.

Okay, so it’s January of 2023, the Republicans are threatening to blow up the economy by not raising the debt ceiling, do we have a problem of too much demand or too little demand? Which way is up?

New York Times columnist Peter Coy weighed in firmly on the side of too much demand in a piece arguing we have to do something about deficits. He tells us:

“Unless you subscribe to modern monetary theory, which holds that deficits don’t matter unless they cause inflation, something has to be done, and soon. In textbook macroeconomics, higher debt leads to ‘higher real interest rates, greater interest payments to foreign investors, reduced business investment and lower consumer investment in durable goods,’ James Poterba, a public finance economist at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, wrote for the Peter G. Peterson Foundation website in 2021.”

Okay, that’s a pretty clear statement of the too much demand story, coming from the foundation created by that great deficit hawk Peter Peterson. But, let’s take a look at Coy’s dismissive comment, “unless you subscribe to modern monetary theory,” and think about the issue at hand.[1]

I have never been a card-carrying member of Modern Monetary Theory (MMT), but I do take its arguments seriously. Let’s say that we run large budget deficits and have the Federal Reserve Board buy up much of the debt. To people who have been alive in the last 15 years, this policy goes under the name “quantitative easing.”

To my knowledge, none of the current or past members of the Fed consider themselves followers of MMT, but they basically followed an MMT prescription. They had the Fed buying up large amounts of debt to keep interest rates low and boost the economy.

The reason this is important is that we don’t get the exploding debt scare story that Coy, along with the Peter Peterson gang, are trying to push. When the Fed buys up bonds, guess who gets the interest on the bonds?

That’s right folks, it goes to the Fed. And, the Fed refunds it to the Treasury. So, our crushing interest burden ends up being a simple accounting transaction where the Treasury essentially ends up paying interest to itself.

Okay, but how long can this go on? The short answer is forever, the slightly longer answer is until we see a problem with inflation. This gets us back to the basic issue, are we worried that we have too much demand or too little demand?

If Larry Summers and other proponents of the secular stagnation view are correct, then we have very little reason to fear exploding budget deficits. Our major concern going forward will be too little demand. That means the Fed can do an awful lot of quantitative easing without causing any problems for the economy.

If that one is stretching people’s brains, let’s look to Japan. It has a debt-to-GDP ratio of 264 percent, the equivalent of a debt of more than $66 trillion in the United States. The interest rate on its long-term bonds is 0.35 percent. Its net interest payments on its government debt come to 0.3 percent of its GDP, compared to 1.7 percent in the United States. And, apart from a modest pandemic uptick, it has been struggling to raise its inflation rate to its central bank’s 2.0 percent target.

Long and short, if Larry Summers and the secular stagnation crew are correct, then the debt fears being pushed by many are unfounded. If, on the other hand, we are likely to run up against real and lasting supply constraints going forward, then too much spending or too little taxes, can be a problem.

What About Patent and Copyright Monopolies?

I just feel the need to ask, since no one else ever does. Granting patent and copyright monopolies is one way the government pays people to do things. For some reason, this obvious point is never mentioned in public discussions of debt and deficits.

If, for example, we were to decide to spend $100 billion more annually (we currently spend a bit more than $50 billion) on biomedical research, we would get an immediate chorus of “how are you going to pay for it?” from all knowledgeable policy types. However, if we tell the drug companies to spend $100 billion a year on research, and we will give you patent monopolies that allow you to raise your prices by $100 billion annually above the free market price, no asks about how we pay for it. Of course, this is exactly what we do, but drug companies use these monopolies to raise their prices by somewhere around $400 billion annually.

Anyhow, it is more than a bit bizarre that almost everyone involved in budget debates has a clear conception of how we can impoverish our kids by imposing high taxes, but it seems none of them have given a second thought to how high prices for drugs, medical equipment, computer software and a whole range of other items, due to government-granted monopolies, can be a burden.

As the saying goes, economists are not very good at economics.

[1] It’s also worth noting that the budget horror stories, past and present, project that health care spending will grow rapidly as a share of GDP. We actually have seen very limited increases in health care spending as a share of GDP, and since the pandemic, the health care spending share has actually fallen.

The economy can have a problem of too much demand, leading to serious inflationary pressures. It can also have a problem of too little demand, leading to slow growth and unemployment. But can it have both at the same time?

Apparently, the leading lights in economic policy circles seem to think so. As I noted a few days ago, back in the 1990s and 00s economists were almost universally warning of the bad effects of an aging population. The issue was that we would have too many retirees and too few workers to support them.

This meant a problem of excess demand. Since much of the money to support retirees comes from government programs for the elderly, like Social Security and Medicare, this meant we would see this show up as large government budget deficits, unless we had big tax increases to reduce demand.

In recent years, this view had largely been replaced with concerns over secular stagnation. This is a story where an aging population implies a slow-growing or shrinking labor force. This reduces the need for investment spending. The reduction in investment spending, coupled with other factors increasing saving, gives what Larry Summers referred to as a “savings glut.” This is a story of too little demand.

Okay, so it’s January of 2023, the Republicans are threatening to blow up the economy by not raising the debt ceiling, do we have a problem of too much demand or too little demand? Which way is up?

New York Times columnist Peter Coy weighed in firmly on the side of too much demand in a piece arguing we have to do something about deficits. He tells us:

“Unless you subscribe to modern monetary theory, which holds that deficits don’t matter unless they cause inflation, something has to be done, and soon. In textbook macroeconomics, higher debt leads to ‘higher real interest rates, greater interest payments to foreign investors, reduced business investment and lower consumer investment in durable goods,’ James Poterba, a public finance economist at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, wrote for the Peter G. Peterson Foundation website in 2021.”

Okay, that’s a pretty clear statement of the too much demand story, coming from the foundation created by that great deficit hawk Peter Peterson. But, let’s take a look at Coy’s dismissive comment, “unless you subscribe to modern monetary theory,” and think about the issue at hand.[1]

I have never been a card-carrying member of Modern Monetary Theory (MMT), but I do take its arguments seriously. Let’s say that we run large budget deficits and have the Federal Reserve Board buy up much of the debt. To people who have been alive in the last 15 years, this policy goes under the name “quantitative easing.”

To my knowledge, none of the current or past members of the Fed consider themselves followers of MMT, but they basically followed an MMT prescription. They had the Fed buying up large amounts of debt to keep interest rates low and boost the economy.

The reason this is important is that we don’t get the exploding debt scare story that Coy, along with the Peter Peterson gang, are trying to push. When the Fed buys up bonds, guess who gets the interest on the bonds?

That’s right folks, it goes to the Fed. And, the Fed refunds it to the Treasury. So, our crushing interest burden ends up being a simple accounting transaction where the Treasury essentially ends up paying interest to itself.

Okay, but how long can this go on? The short answer is forever, the slightly longer answer is until we see a problem with inflation. This gets us back to the basic issue, are we worried that we have too much demand or too little demand?

If Larry Summers and other proponents of the secular stagnation view are correct, then we have very little reason to fear exploding budget deficits. Our major concern going forward will be too little demand. That means the Fed can do an awful lot of quantitative easing without causing any problems for the economy.

If that one is stretching people’s brains, let’s look to Japan. It has a debt-to-GDP ratio of 264 percent, the equivalent of a debt of more than $66 trillion in the United States. The interest rate on its long-term bonds is 0.35 percent. Its net interest payments on its government debt come to 0.3 percent of its GDP, compared to 1.7 percent in the United States. And, apart from a modest pandemic uptick, it has been struggling to raise its inflation rate to its central bank’s 2.0 percent target.

Long and short, if Larry Summers and the secular stagnation crew are correct, then the debt fears being pushed by many are unfounded. If, on the other hand, we are likely to run up against real and lasting supply constraints going forward, then too much spending or too little taxes, can be a problem.

What About Patent and Copyright Monopolies?

I just feel the need to ask, since no one else ever does. Granting patent and copyright monopolies is one way the government pays people to do things. For some reason, this obvious point is never mentioned in public discussions of debt and deficits.

If, for example, we were to decide to spend $100 billion more annually (we currently spend a bit more than $50 billion) on biomedical research, we would get an immediate chorus of “how are you going to pay for it?” from all knowledgeable policy types. However, if we tell the drug companies to spend $100 billion a year on research, and we will give you patent monopolies that allow you to raise your prices by $100 billion annually above the free market price, no asks about how we pay for it. Of course, this is exactly what we do, but drug companies use these monopolies to raise their prices by somewhere around $400 billion annually.

Anyhow, it is more than a bit bizarre that almost everyone involved in budget debates has a clear conception of how we can impoverish our kids by imposing high taxes, but it seems none of them have given a second thought to how high prices for drugs, medical equipment, computer software and a whole range of other items, due to government-granted monopolies, can be a burden.

As the saying goes, economists are not very good at economics.

[1] It’s also worth noting that the budget horror stories, past and present, project that health care spending will grow rapidly as a share of GDP. We actually have seen very limited increases in health care spending as a share of GDP, and since the pandemic, the health care spending share has actually fallen.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

I rarely disagree in a big way with Paul Krugman, but I think he misses the boat in an important way in his piece on China’s alleged demographic crisis. Before getting to my point of disagreement, first let me emphasis a key point of agreement.

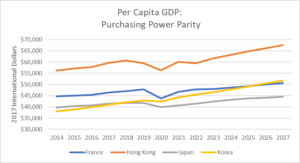

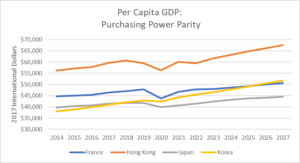

Krugman points out that many countries, notably Japan, have managed to do just fine in the face of a declining population and shrinking workforce. Their people continue to enjoy rising standards of living as their population shrinks. In the case of Japan, its population has been declining for more than a decade and its workforce has been pretty much stagnant over this period. Nonetheless, its per capita income is nearly 10 percent higher than it was a decade ago.

This actually understates the improvement in living standards enjoyed by the Japanese population over this period. The average number of hours worked in a year also fell by more than 7.0 percent, meaning a typical Japanese worker has more leisure time now than they did a decade ago.

It’s also worth mentioning that Japan’s cities are less crowded than they would be if its population had continued to grow. This means less congestion and pollution, less time spent getting to and from work, and less crowded, beaches, parks, and museums. These quality of life factors don’t get picked up in GDP.

Japan has been running large deficits and built up a large debt to sustain economic growth in the last two decades, but this has not created a major burden for its economy. Its interest payments on its debt are less than 0.3 percent of GDP, compared to 1.7 percent of GDP for the United States. Its inflation rate has consistently been well below its central bank’s 2.0 percent target, although it did see a modest Covid uptick in the last two years.

This point about inflation is central. Back in the good old days, when the Peter Peterson anti-Social Security warriors were in their prime in the 1990s, the standard story on an aging society was that we would have too few workers to support all the old-timers. The retirement of the baby boomers was supposed to break the camel’s back. There would have to be massive tax increases, otherwise the government would run huge deficits which would lead to cascading interest payments on the debt. Alternatively, it could finance its deficits by printing money, leading to out of control inflation.

The Peterson story was never very honest, since the real factor driving its deficit horror story was the projection of exploding private sector health care costs. Since the government picks up roughly half the national tab on health care through programs like Medicare and Medicaid, the explosion in health care costs then being projected would have meant a massive burden on the public sector, even without the aging of the population.

As it turns out, we didn’t see anywhere near the explosive growth in health care costs projected at the time, but we have seen the aging of the population and an increase in the ratio of retirees to workers. But rather than seeing excess demand (Covid shutdown and recovery excepted), our problem has been inadequate demand. The same problem that has afflicted Japan.

This story, which now passes under the name of “secular stagnation,” is 180 degrees opposite the problem pushed by the deficit hawks. Back then, the problem of an aging population was supposed to be that we would be seeing so much demand that our shrinking labor force would not be able to produce enough goods and services. Now the story is that we see less demand with our aging population, so we will see weak growth, unemployment, and deflation.

It’s good that the economics profession has been able to adjust its theories to reality, but we should at least acknowledge the complete shift in perspectives. It is a bit embarrassing that the nearly universally accepted dogma within the profession twenty or thirty years ago proved to be the exact opposite of the reality.

On to China!

Okay, now that we know the terrain, the question is whether China should be terrified that its population is now falling, as all our leading news outlets are telling us? Well, as people who have listened to the media’s sky is falling tales should recognize, China’s falling population crisis is just our old friend, the story of not enough workers to meet the demands of an aging population.[1] So the question is whether China’s economy will be able to meet the demands created by a growing population of retirees.

As Krugman correctly points out in his column, there is no reason in principle that China should not be able to support its elderly. The question is a political one of whether its government is prepared to establish adequate Social Security and Medicare-type systems to ensure that its elderly have sufficient income and decent health care. Not having any special expertise on China’s politics, I can’t answer that question, but it is important to recognize that it is not a problem of an inadequate labor force.

Where Krugman left me scratching my head was his discussion of this problem of shifting resources to support the elderly:

“For China has long had a wildly unbalanced economy. For reasons I admit I don’t fully understand, policymakers there have been reluctant to allow the full benefits of past economic growth to pass through to households, and that has led to relatively low consumer demand.

“Instead, China has sustained its economy with extremely high rates of investment, far higher even than those that prevailed in Japan at the height of its infamous late-1980s bubble. Normally, investing in the future is good, but when extremely high investment collides with a falling population, much of that investment inevitably yields diminishing returns.”

There are two points I would make here. First, while Krugman is entirely right about the high rates of investment preventing households from enjoying the full benefits of economic growth, it is worth noting that China’s population has enjoyed enormous improvements in living standards over the last four decades. In the 1970s, the standard of living for the bulk of the population was only slightly better in many respects than for people in Sub Saharan Africa.

Today, hundreds of millions of people in China have near European standards of living. Krugman is right that the country’s growth could allow for even more gains (especially in rural areas), but the enormous gains seen by the bulk of the population probably meant that there was more tolerance for waste than in a context where say, a declining workforce was leading to stagnant or declining living standards.

The other point is simply the flip side of Krugman’s point about the massive investment spending in China. This is a waste of resources that can in principle be converted to meet the needs of the elderly population. In other words, if anyone believed the not enough workers story, we can point to all the people and resources tied up in nearly pointless investment projects. They could instead be building hospitals, retirement facilities, and in other ways producing the goods and services demanded by a growing elderly population. Of course, China couldn’t accomplish this sort of conversion overnight, but its population isn’t aging overnight.

Again, if China can undertake this sort of conversion is a political question. Maybe people more expert on China’s politics can answer it, but it clearly is not an issue of too few workers to meet the demands of an aging population.

One final issue: as I have pointed out on many occasions, the impact of even modest rates of productivity growth swamp the impact of demographics. China’s productivity growth has slowed in recent years, but even at a pace of 3-4 percent annually (what we have been seeing in recent years), it should easily be able to produce enough so that in ten or twenty years both workers and retirees can enjoy much higher living standards than they do today.

Whether its productivity growth will continue at recent rates, or slow further, is an open question, but anyone claiming that it will not have enough output to be able to support its retirees is predicting a massive slowing of productivity growth. For what it’s worth, the International Monetary Fund (I.M.F) is projecting that China continues to sustain strong productivity growth. It projects that GDP growth will average more than 4.5 percent annually even as its workforce shrinks.

The I.M.F. projection can of course be wrong, but clearly it does not accept the declining population crisis story. For now, that one is best filed under “fiction.”

[1] There is also the silliness around turning negative. There is very little difference to the economy if its population or labor force is shrinking slowly, say 0.2 percent a year, or growing by the same amount. We saw the same hysteria around the issue of deflation, as though economies would somehow face a crisis if their rate of inflation was a small negative number instead of a small positive number. The lesson that actually serious people everywhere know, is that crossing zero doesn’t matter.

I rarely disagree in a big way with Paul Krugman, but I think he misses the boat in an important way in his piece on China’s alleged demographic crisis. Before getting to my point of disagreement, first let me emphasis a key point of agreement.

Krugman points out that many countries, notably Japan, have managed to do just fine in the face of a declining population and shrinking workforce. Their people continue to enjoy rising standards of living as their population shrinks. In the case of Japan, its population has been declining for more than a decade and its workforce has been pretty much stagnant over this period. Nonetheless, its per capita income is nearly 10 percent higher than it was a decade ago.

This actually understates the improvement in living standards enjoyed by the Japanese population over this period. The average number of hours worked in a year also fell by more than 7.0 percent, meaning a typical Japanese worker has more leisure time now than they did a decade ago.

It’s also worth mentioning that Japan’s cities are less crowded than they would be if its population had continued to grow. This means less congestion and pollution, less time spent getting to and from work, and less crowded, beaches, parks, and museums. These quality of life factors don’t get picked up in GDP.

Japan has been running large deficits and built up a large debt to sustain economic growth in the last two decades, but this has not created a major burden for its economy. Its interest payments on its debt are less than 0.3 percent of GDP, compared to 1.7 percent of GDP for the United States. Its inflation rate has consistently been well below its central bank’s 2.0 percent target, although it did see a modest Covid uptick in the last two years.

This point about inflation is central. Back in the good old days, when the Peter Peterson anti-Social Security warriors were in their prime in the 1990s, the standard story on an aging society was that we would have too few workers to support all the old-timers. The retirement of the baby boomers was supposed to break the camel’s back. There would have to be massive tax increases, otherwise the government would run huge deficits which would lead to cascading interest payments on the debt. Alternatively, it could finance its deficits by printing money, leading to out of control inflation.

The Peterson story was never very honest, since the real factor driving its deficit horror story was the projection of exploding private sector health care costs. Since the government picks up roughly half the national tab on health care through programs like Medicare and Medicaid, the explosion in health care costs then being projected would have meant a massive burden on the public sector, even without the aging of the population.

As it turns out, we didn’t see anywhere near the explosive growth in health care costs projected at the time, but we have seen the aging of the population and an increase in the ratio of retirees to workers. But rather than seeing excess demand (Covid shutdown and recovery excepted), our problem has been inadequate demand. The same problem that has afflicted Japan.

This story, which now passes under the name of “secular stagnation,” is 180 degrees opposite the problem pushed by the deficit hawks. Back then, the problem of an aging population was supposed to be that we would be seeing so much demand that our shrinking labor force would not be able to produce enough goods and services. Now the story is that we see less demand with our aging population, so we will see weak growth, unemployment, and deflation.

It’s good that the economics profession has been able to adjust its theories to reality, but we should at least acknowledge the complete shift in perspectives. It is a bit embarrassing that the nearly universally accepted dogma within the profession twenty or thirty years ago proved to be the exact opposite of the reality.

On to China!

Okay, now that we know the terrain, the question is whether China should be terrified that its population is now falling, as all our leading news outlets are telling us? Well, as people who have listened to the media’s sky is falling tales should recognize, China’s falling population crisis is just our old friend, the story of not enough workers to meet the demands of an aging population.[1] So the question is whether China’s economy will be able to meet the demands created by a growing population of retirees.

As Krugman correctly points out in his column, there is no reason in principle that China should not be able to support its elderly. The question is a political one of whether its government is prepared to establish adequate Social Security and Medicare-type systems to ensure that its elderly have sufficient income and decent health care. Not having any special expertise on China’s politics, I can’t answer that question, but it is important to recognize that it is not a problem of an inadequate labor force.

Where Krugman left me scratching my head was his discussion of this problem of shifting resources to support the elderly:

“For China has long had a wildly unbalanced economy. For reasons I admit I don’t fully understand, policymakers there have been reluctant to allow the full benefits of past economic growth to pass through to households, and that has led to relatively low consumer demand.

“Instead, China has sustained its economy with extremely high rates of investment, far higher even than those that prevailed in Japan at the height of its infamous late-1980s bubble. Normally, investing in the future is good, but when extremely high investment collides with a falling population, much of that investment inevitably yields diminishing returns.”

There are two points I would make here. First, while Krugman is entirely right about the high rates of investment preventing households from enjoying the full benefits of economic growth, it is worth noting that China’s population has enjoyed enormous improvements in living standards over the last four decades. In the 1970s, the standard of living for the bulk of the population was only slightly better in many respects than for people in Sub Saharan Africa.

Today, hundreds of millions of people in China have near European standards of living. Krugman is right that the country’s growth could allow for even more gains (especially in rural areas), but the enormous gains seen by the bulk of the population probably meant that there was more tolerance for waste than in a context where say, a declining workforce was leading to stagnant or declining living standards.

The other point is simply the flip side of Krugman’s point about the massive investment spending in China. This is a waste of resources that can in principle be converted to meet the needs of the elderly population. In other words, if anyone believed the not enough workers story, we can point to all the people and resources tied up in nearly pointless investment projects. They could instead be building hospitals, retirement facilities, and in other ways producing the goods and services demanded by a growing elderly population. Of course, China couldn’t accomplish this sort of conversion overnight, but its population isn’t aging overnight.

Again, if China can undertake this sort of conversion is a political question. Maybe people more expert on China’s politics can answer it, but it clearly is not an issue of too few workers to meet the demands of an aging population.

One final issue: as I have pointed out on many occasions, the impact of even modest rates of productivity growth swamp the impact of demographics. China’s productivity growth has slowed in recent years, but even at a pace of 3-4 percent annually (what we have been seeing in recent years), it should easily be able to produce enough so that in ten or twenty years both workers and retirees can enjoy much higher living standards than they do today.

Whether its productivity growth will continue at recent rates, or slow further, is an open question, but anyone claiming that it will not have enough output to be able to support its retirees is predicting a massive slowing of productivity growth. For what it’s worth, the International Monetary Fund (I.M.F) is projecting that China continues to sustain strong productivity growth. It projects that GDP growth will average more than 4.5 percent annually even as its workforce shrinks.

The I.M.F. projection can of course be wrong, but clearly it does not accept the declining population crisis story. For now, that one is best filed under “fiction.”

[1] There is also the silliness around turning negative. There is very little difference to the economy if its population or labor force is shrinking slowly, say 0.2 percent a year, or growing by the same amount. We saw the same hysteria around the issue of deflation, as though economies would somehow face a crisis if their rate of inflation was a small negative number instead of a small positive number. The lesson that actually serious people everywhere know, is that crossing zero doesn’t matter.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

• InequalityLa DesigualdadUnited StatesEE. UU.

I was happy to see this segment of Ezra Klein’s show (hosted by Rogé Karma) which featured an interview with Columbia University Law Professor Katharina Pistor. Pistor is the author of The Code of Capital: How the Law Creates Wealth and Inequality.

I’ve not yet read the book, but got the gist from the interview. Pistor is arguing that we have structured the market in ways that generate enormous inequality. In the interview, she presents several ways in which the law has been written that facilitate the accumulation of wealth by a small group of people. These include rules on property in land, intellectual property, and the creation of corporations as distinct entities with an existence independent of their owners.

Pistor’s point is that the way these rules are structured is not set in stone. They can be written differently so that they don’t lead to so much inequality.[1] Having written several books and endless blogposts in this vein, Pistor’s interview almost made my day. (There is also the video version.)

I say almost because, even though her work was getting a high-profile spot in the New York Times (and I gather her book has also been well-received), I doubt very much that any of the intellectual types who write on politics will absorb its main point. With few exceptions, the people who write about and pontificate on politics have their brain hard-wired to the view that liberals want the government and conservatives want to leave things to the market. They insist that this is the main conflict in political debates both in the United States and around the world.

Of course, Pistor’s point is that we have allowed the market to be structured in a way that leads to an enormous share of income flowing to those at the top. We didn’t have to do it that way.

We don’t need to have patent and copyright monopolies and other forms of intellectual property. Creating intellectual property and making these monopolies longer and stronger is a political decision. It has led to enormous inequality, both in making people like Bill Gates tremendously wealthy, and also providing the basis for the alleged bias in technology that allows people with STEM skills to do very well in the current economy. STEM skills would likely be far less valuable in an economy that had weaker intellectual property rules and relied more on alternative methods to finance innovation and creative work.

There is a similar story with rules on incorporation. We don’t have to give corporations legal personhood, as our courts have done. We can also have different rules of corporate governance that make it more difficult for top executives to pay themselves salaries in the tens of millions annually.

I can go on at length on this, as I have. Those who are interested can read my books (they are free) or Pistor’s. But the point is that the market has been structured in ways that lead to enormous inequality. It could be structured differently.

Taking the current structure of the market as a given puts progressives at an enormous disadvantage. To my view, government social programs like Social Security, Medicare, and public education are enormously important. But the need for redistributive program increases enormously if we allow the market to be structured in a way that leads to massive inequality. And, the ability for pay for them decreases, especially in a political system that allows the wealthy to have such disproportionate influence.

Accepting that conservatives want the free market, after we have allowed them to rig the rules to redistribute massive amounts of income upward, is like saying that supporters of grandfather rules for voting believed in race-blind democracy. After all, anyone whose grandfather was a registered voter was eligible to vote, regardless of race. Defining the battle lines as being about the role of the government versus the market, as opposed to a battle over the structure of the market, essentially gives away the store.

If there is a counter anywhere to the argument that Pistor is making (others have also made a similar argument, notably Yale political science professor Jacob Hacker), I have not seen it and cannot imagine what it would be. The rules of the market are pretty much infinitely malleable. There is no natural market outcome. Many right-wingers may want the world to believe the rules of the market are just given to us by god or nature, but nothing could be further from the truth.

For some reason, this point doesn’t seem to affect political debate. I suspect that even the people embracing Pistor’s argument last week will turn around in the near future and tell us that conservatives want to leave things to the market. It seems that, even though the structure of the market is not fixed by god or nature, it is a fact of nature that this view must be central to our political debates.

[1] Pistor repeatedly refers to these rules as “fictions.” I think that framing is unfortunate. The rules are very real, but her point, as I take it, is that they could be different. The fact that something is socially created doesn’t make it fiction.

I was happy to see this segment of Ezra Klein’s show (hosted by Rogé Karma) which featured an interview with Columbia University Law Professor Katharina Pistor. Pistor is the author of The Code of Capital: How the Law Creates Wealth and Inequality.

I’ve not yet read the book, but got the gist from the interview. Pistor is arguing that we have structured the market in ways that generate enormous inequality. In the interview, she presents several ways in which the law has been written that facilitate the accumulation of wealth by a small group of people. These include rules on property in land, intellectual property, and the creation of corporations as distinct entities with an existence independent of their owners.

Pistor’s point is that the way these rules are structured is not set in stone. They can be written differently so that they don’t lead to so much inequality.[1] Having written several books and endless blogposts in this vein, Pistor’s interview almost made my day. (There is also the video version.)

I say almost because, even though her work was getting a high-profile spot in the New York Times (and I gather her book has also been well-received), I doubt very much that any of the intellectual types who write on politics will absorb its main point. With few exceptions, the people who write about and pontificate on politics have their brain hard-wired to the view that liberals want the government and conservatives want to leave things to the market. They insist that this is the main conflict in political debates both in the United States and around the world.

Of course, Pistor’s point is that we have allowed the market to be structured in a way that leads to an enormous share of income flowing to those at the top. We didn’t have to do it that way.

We don’t need to have patent and copyright monopolies and other forms of intellectual property. Creating intellectual property and making these monopolies longer and stronger is a political decision. It has led to enormous inequality, both in making people like Bill Gates tremendously wealthy, and also providing the basis for the alleged bias in technology that allows people with STEM skills to do very well in the current economy. STEM skills would likely be far less valuable in an economy that had weaker intellectual property rules and relied more on alternative methods to finance innovation and creative work.

There is a similar story with rules on incorporation. We don’t have to give corporations legal personhood, as our courts have done. We can also have different rules of corporate governance that make it more difficult for top executives to pay themselves salaries in the tens of millions annually.

I can go on at length on this, as I have. Those who are interested can read my books (they are free) or Pistor’s. But the point is that the market has been structured in ways that lead to enormous inequality. It could be structured differently.

Taking the current structure of the market as a given puts progressives at an enormous disadvantage. To my view, government social programs like Social Security, Medicare, and public education are enormously important. But the need for redistributive program increases enormously if we allow the market to be structured in a way that leads to massive inequality. And, the ability for pay for them decreases, especially in a political system that allows the wealthy to have such disproportionate influence.

Accepting that conservatives want the free market, after we have allowed them to rig the rules to redistribute massive amounts of income upward, is like saying that supporters of grandfather rules for voting believed in race-blind democracy. After all, anyone whose grandfather was a registered voter was eligible to vote, regardless of race. Defining the battle lines as being about the role of the government versus the market, as opposed to a battle over the structure of the market, essentially gives away the store.

If there is a counter anywhere to the argument that Pistor is making (others have also made a similar argument, notably Yale political science professor Jacob Hacker), I have not seen it and cannot imagine what it would be. The rules of the market are pretty much infinitely malleable. There is no natural market outcome. Many right-wingers may want the world to believe the rules of the market are just given to us by god or nature, but nothing could be further from the truth.

For some reason, this point doesn’t seem to affect political debate. I suspect that even the people embracing Pistor’s argument last week will turn around in the near future and tell us that conservatives want to leave things to the market. It seems that, even though the structure of the market is not fixed by god or nature, it is a fact of nature that this view must be central to our political debates.

[1] Pistor repeatedly refers to these rules as “fictions.” I think that framing is unfortunate. The rules are very real, but her point, as I take it, is that they could be different. The fact that something is socially created doesn’t make it fiction.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

• Intellectual PropertyPropiedad IntelectualUnited StatesEE. UU.

A Washington Post editorial, following the outcome of a Congressional investigation, complained that the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) wrongly moved ahead with an accelerated approval process for the Alzheimer’s drug Adulhelm. It then approved a label that suggested the drug, which was being marketed for $56,000 for a year’s dosage, could be a general treatment for Alzheimer’s, even though the clinical trial evidence suggested it was at best appropriate for a small portion of patients with Alzheimer’s.

The editorial attributed the special treatment of the drug to the close relationship between Biogen, the drug’s manufacturer, and FDA staff. It implied that if there had been a more arms-length relationship, the FDA would not have been so positive towards the drug.

Missing from the editorial is any discussion of the government-granted patent monopolies that provide the incentive for this sort of corruption. If Adulhelm was being assessed for approval as a generic, selling for a few hundred dollars a year, there would be little incentive for its developers to devote lots of time and money to push the FDA to approve it, when the clinical trial data did not show clear evidence of its effectiveness. It was only the enormous amount of money at stake from having a monopoly on a presumably effective Alzheimer’s drug that gave Biogen the incentive to push the FDA to take steps not warranted by the evidence.

It is striking that the Washington Post can’t see the connection between granting patent monopolies, that can raise drug prices by 10,000 percent above the free market price, and corruption. It routinely complains about the corruption that can result from trade tariffs that may raise the price of manufacturers goods by 10-25 percent above the free market price.

There are alternative mechanisms for financing the development of prescription drugs, such as direct government funding, as we currently have with the National Institutes of Health. (See here and chapter 5 of Rigged [it’s free].) Apparently, the Washington Post does not allow these alternatives to be discussed in its pages, even as it notes the dangers of the patent monopoly system.

A Washington Post editorial, following the outcome of a Congressional investigation, complained that the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) wrongly moved ahead with an accelerated approval process for the Alzheimer’s drug Adulhelm. It then approved a label that suggested the drug, which was being marketed for $56,000 for a year’s dosage, could be a general treatment for Alzheimer’s, even though the clinical trial evidence suggested it was at best appropriate for a small portion of patients with Alzheimer’s.

The editorial attributed the special treatment of the drug to the close relationship between Biogen, the drug’s manufacturer, and FDA staff. It implied that if there had been a more arms-length relationship, the FDA would not have been so positive towards the drug.

Missing from the editorial is any discussion of the government-granted patent monopolies that provide the incentive for this sort of corruption. If Adulhelm was being assessed for approval as a generic, selling for a few hundred dollars a year, there would be little incentive for its developers to devote lots of time and money to push the FDA to approve it, when the clinical trial data did not show clear evidence of its effectiveness. It was only the enormous amount of money at stake from having a monopoly on a presumably effective Alzheimer’s drug that gave Biogen the incentive to push the FDA to take steps not warranted by the evidence.

It is striking that the Washington Post can’t see the connection between granting patent monopolies, that can raise drug prices by 10,000 percent above the free market price, and corruption. It routinely complains about the corruption that can result from trade tariffs that may raise the price of manufacturers goods by 10-25 percent above the free market price.

There are alternative mechanisms for financing the development of prescription drugs, such as direct government funding, as we currently have with the National Institutes of Health. (See here and chapter 5 of Rigged [it’s free].) Apparently, the Washington Post does not allow these alternatives to be discussed in its pages, even as it notes the dangers of the patent monopoly system.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Like all good Keynesian economists, I’m a big fan of the platinum coin. The law explicitly allows the Treasury to print platinum coins in any denomination. That means it absolutely could deal with the debt ceiling by printing a platinum coin denominated for $1 trillion and selling it to the Fed.

This would not count as debt for debt ceiling purposes. The government would have sold an asset, the coin, in exchange for $1 trillion that it could then use to meet its bills. From an accounting standpoint, it would be the same thing as selling off blocs of government land for $1 trillion.

Unfortunately, the Biden administration seems reluctant to go the coin route, at least for now. But there is a slightly less gimmicky way for the Treasury to buy some room on the debt ceiling.

In 2020 and 2021 the Treasury issued trillions of dollars of debt at very low interest rates. Much of this was longer term debt, with maturities of 10 or even 30 years. Since interest rates are now much higher (the interest rate on 10-year Treasury bonds is now near 3.5 percent), the bonds issued at low interest rates in 2020 and 2021 would sell for much lower prices in the market today.

This might mean, for example, that a $1,000 10-year Treasury bond, issued at an interest rate of less than 1.0 percent in the summer of 2020, would sell for just $850 in the market today. For purposes of the debt ceiling, the law calculates debt at its face value, rather than its market value.

This means that Treasury could buy this bond for $850, and thereby reduce the value of outstanding debt by $150. With trillions of dollars of debt now selling for prices that are lower, and in some cases substantially lower, than their face value, the Treasury can reduce the amount of outstanding debt by hundreds of billions of dollars simply by buying up this debt at the current market price.

This will not end the standoff, we are running large deficits and eventually the Treasury will run out of bonds to buy, but this move could allow President Biden to delay the standoff over the debt ceiling for many months. (Maybe he’ll get out the coin at that point.)

As policy, this is of course absurd. The government has better things to do than to play around shuffling Treasury bonds. But the debt ceiling is also absurd. So, like the coin, it is an absurd solution to an absurd problem.

This sort of scheming on manipulating the measured size of the debt is not new, some of us have played with it for a long time. But absurd standoffs on the debt are also not new, so it’s always good to remember our stock of off-the-shelf fixes.

Like all good Keynesian economists, I’m a big fan of the platinum coin. The law explicitly allows the Treasury to print platinum coins in any denomination. That means it absolutely could deal with the debt ceiling by printing a platinum coin denominated for $1 trillion and selling it to the Fed.

This would not count as debt for debt ceiling purposes. The government would have sold an asset, the coin, in exchange for $1 trillion that it could then use to meet its bills. From an accounting standpoint, it would be the same thing as selling off blocs of government land for $1 trillion.

Unfortunately, the Biden administration seems reluctant to go the coin route, at least for now. But there is a slightly less gimmicky way for the Treasury to buy some room on the debt ceiling.

In 2020 and 2021 the Treasury issued trillions of dollars of debt at very low interest rates. Much of this was longer term debt, with maturities of 10 or even 30 years. Since interest rates are now much higher (the interest rate on 10-year Treasury bonds is now near 3.5 percent), the bonds issued at low interest rates in 2020 and 2021 would sell for much lower prices in the market today.

This might mean, for example, that a $1,000 10-year Treasury bond, issued at an interest rate of less than 1.0 percent in the summer of 2020, would sell for just $850 in the market today. For purposes of the debt ceiling, the law calculates debt at its face value, rather than its market value.

This means that Treasury could buy this bond for $850, and thereby reduce the value of outstanding debt by $150. With trillions of dollars of debt now selling for prices that are lower, and in some cases substantially lower, than their face value, the Treasury can reduce the amount of outstanding debt by hundreds of billions of dollars simply by buying up this debt at the current market price.

This will not end the standoff, we are running large deficits and eventually the Treasury will run out of bonds to buy, but this move could allow President Biden to delay the standoff over the debt ceiling for many months. (Maybe he’ll get out the coin at that point.)

As policy, this is of course absurd. The government has better things to do than to play around shuffling Treasury bonds. But the debt ceiling is also absurd. So, like the coin, it is an absurd solution to an absurd problem.

This sort of scheming on manipulating the measured size of the debt is not new, some of us have played with it for a long time. But absurd standoffs on the debt are also not new, so it’s always good to remember our stock of off-the-shelf fixes.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The December Consumer Price Index (CPI), following a great December jobs report, shows the economy has turned the corner and seems on a path to stable growth with moderate inflation. The CPI showed prices actually fell by 0.1 percent for the month. This brought the annualized rate of inflation over the last three months in the overall index to just 1.8 percent.

With the drop in prices reported in December, the real average hourly wage for all workers is now 0.3 percent above its pre-pandemic level. For production and non-supervisory workers it is 0.8 percent higher. And, for production and non-supervisory workers in the low-paying hotel and restaurant sector it is up 5.7 percent.

The overall index for December was held down by a 4.5 percent plunge in energy prices, but the 0.3 percent rise in the core index should not be terribly troubling. The biggest factor pushing the core index higher was a 0.8 percent rise in both the rent proper index and the owners equivalent rent index, which together comprise almost 40 percent of the core index. The core index, excluding shelter, fell by 0.1 percent in December.

We know the rent indexes will be showing much lower inflation in 2023, and possibly even deflation, based on private indexes of rents in marketed units. Research from the Bureau of Labor Statistics shows that these private indexes lead the CPI rent indexes by six months to a year. With inflation in these indexes having turned downward in the summer, we know that in the not distant future, the inflation rate shown in the CPI rent indexes will fall sharply.

After leading the surge in inflation in 2021 and the first half of this year, due to supply chain problems, most goods are now seeing flat or falling prices. New vehicle prices fell 0.1 percent, the first drop since January of 2021. With demand for vehicles slowing, and most production largely back to normal, we should be seeing more drops in vehicle prices going forward.

Used vehicle prices fell by 2.5 percent in December, continuing a decline that began in July, but with prices still almost 40 percent higher than their pre-pandemic level, they have much further to fall. Prices of other items driven up by supply chain issues, like apparel, furniture, and appliances, were mixed in December, but there is little doubt that the direction in 2023 will be flat or downward.

With goods inflation clearly under control, the Fed has said that it wanted to focus on non-rent services. Here also the picture was largely positive in December. The index for medical services rose just 0.1 percent, although it was held down by an anomalous 3.4 percent decline in the health insurance index. But even pulling this out the picture is mixed at worst. The index for professional medical services rose just 0.1 percent, putting the year over year increase at 3.0 percent. The index for hospital services rose a more concerning 1.5 percent, but that followed declines in the prior two months. It is up 4.6 percent year over year.

The picture in other services is mixed. Recreation services rose 0.3 percent, well below the rates in recent months. The index is up 5.7 percent over the year. College tuition rose 0.3 percent in December, putting the year over year increase at 2.3 percent. Transportation services rose 0.2 percent, but the year over year increase is a still a double-digit 14.6 percent.

A big factor in the year over year rise is a 28.5 percent jump in air fares, which was reversing the decline earlier in the pandemic. Air fares actually fell by 3.1 percent in December.

But there also have been sharp increases in other components of transportation services. Car repairs rose 1.0 percent in December and are up 13.0 percent year over year. The auto insurance index rose 0.6 percent in the month and 14.2 percent over the last year.

These sharp increases show how the supply chain goods problems are intertwined with the service indexes. The index for motor vehicle parts and equipment rose 9.9 percent over the last year. These increases get passed on the price of the services. With the supply chain problems now largely under control, these price pressures will lessen in the months ahead, but some of the price increase in these services is reflecting price hikes in inputs from earlier in the year. As the prices of these inputs level off, or even fall, we should see slower inflation in these services.

This is similar to the story with restaurant prices. These rose 0.4 percent in December and are up 8.3 percent over the last year. Some of this rise is due to the reduction in government subsidies for school lunches, the price of which rose 305.2 percent over the last year. But inflation in the larger category was driven to a substantial extent by an 11.8 percent rise in the price of store-bought food.

We actually got some very good news in that category in December, as grocery prices rose just 0.2 percent, the smallest increase since March of 2021. Chicken prices actually fell by 0.6 percent in the month and milk prices dropped by 1.0 percent, although the indexes for both are still up by double digit amounts year over year.

It is likely that we will see more good news on food prices going forward. The price of many commodities, like wheat, corn, and coffee, have fallen sharply from pandemic peaks. With shipping costs also having reversed the vast majority of their pandemic increases, we should be seeing lower prices for many food items in stores.

We always need caution when looking at a single month’s report, but the good December CPI report follows several months in which inflation has slowed sharply from the pace earlier in the year. All the evidence suggests that the economy is still growing at solid pace. (The latest projection for the fourth quarter from the Atlanta Fed’s GDPNow is 4.1 percent.)

It looks like the Fed has largely accomplished its mission of taming inflation, without bringing on a recession. Plenty of things can mess up this picture, like another surge of Covid or an escalation of the war in Ukraine, but for now, the economy is looking very good.

The December Consumer Price Index (CPI), following a great December jobs report, shows the economy has turned the corner and seems on a path to stable growth with moderate inflation. The CPI showed prices actually fell by 0.1 percent for the month. This brought the annualized rate of inflation over the last three months in the overall index to just 1.8 percent.

With the drop in prices reported in December, the real average hourly wage for all workers is now 0.3 percent above its pre-pandemic level. For production and non-supervisory workers it is 0.8 percent higher. And, for production and non-supervisory workers in the low-paying hotel and restaurant sector it is up 5.7 percent.

The overall index for December was held down by a 4.5 percent plunge in energy prices, but the 0.3 percent rise in the core index should not be terribly troubling. The biggest factor pushing the core index higher was a 0.8 percent rise in both the rent proper index and the owners equivalent rent index, which together comprise almost 40 percent of the core index. The core index, excluding shelter, fell by 0.1 percent in December.

We know the rent indexes will be showing much lower inflation in 2023, and possibly even deflation, based on private indexes of rents in marketed units. Research from the Bureau of Labor Statistics shows that these private indexes lead the CPI rent indexes by six months to a year. With inflation in these indexes having turned downward in the summer, we know that in the not distant future, the inflation rate shown in the CPI rent indexes will fall sharply.

After leading the surge in inflation in 2021 and the first half of this year, due to supply chain problems, most goods are now seeing flat or falling prices. New vehicle prices fell 0.1 percent, the first drop since January of 2021. With demand for vehicles slowing, and most production largely back to normal, we should be seeing more drops in vehicle prices going forward.

Used vehicle prices fell by 2.5 percent in December, continuing a decline that began in July, but with prices still almost 40 percent higher than their pre-pandemic level, they have much further to fall. Prices of other items driven up by supply chain issues, like apparel, furniture, and appliances, were mixed in December, but there is little doubt that the direction in 2023 will be flat or downward.

With goods inflation clearly under control, the Fed has said that it wanted to focus on non-rent services. Here also the picture was largely positive in December. The index for medical services rose just 0.1 percent, although it was held down by an anomalous 3.4 percent decline in the health insurance index. But even pulling this out the picture is mixed at worst. The index for professional medical services rose just 0.1 percent, putting the year over year increase at 3.0 percent. The index for hospital services rose a more concerning 1.5 percent, but that followed declines in the prior two months. It is up 4.6 percent year over year.

The picture in other services is mixed. Recreation services rose 0.3 percent, well below the rates in recent months. The index is up 5.7 percent over the year. College tuition rose 0.3 percent in December, putting the year over year increase at 2.3 percent. Transportation services rose 0.2 percent, but the year over year increase is a still a double-digit 14.6 percent.

A big factor in the year over year rise is a 28.5 percent jump in air fares, which was reversing the decline earlier in the pandemic. Air fares actually fell by 3.1 percent in December.

But there also have been sharp increases in other components of transportation services. Car repairs rose 1.0 percent in December and are up 13.0 percent year over year. The auto insurance index rose 0.6 percent in the month and 14.2 percent over the last year.

These sharp increases show how the supply chain goods problems are intertwined with the service indexes. The index for motor vehicle parts and equipment rose 9.9 percent over the last year. These increases get passed on the price of the services. With the supply chain problems now largely under control, these price pressures will lessen in the months ahead, but some of the price increase in these services is reflecting price hikes in inputs from earlier in the year. As the prices of these inputs level off, or even fall, we should see slower inflation in these services.

This is similar to the story with restaurant prices. These rose 0.4 percent in December and are up 8.3 percent over the last year. Some of this rise is due to the reduction in government subsidies for school lunches, the price of which rose 305.2 percent over the last year. But inflation in the larger category was driven to a substantial extent by an 11.8 percent rise in the price of store-bought food.

We actually got some very good news in that category in December, as grocery prices rose just 0.2 percent, the smallest increase since March of 2021. Chicken prices actually fell by 0.6 percent in the month and milk prices dropped by 1.0 percent, although the indexes for both are still up by double digit amounts year over year.

It is likely that we will see more good news on food prices going forward. The price of many commodities, like wheat, corn, and coffee, have fallen sharply from pandemic peaks. With shipping costs also having reversed the vast majority of their pandemic increases, we should be seeing lower prices for many food items in stores.

We always need caution when looking at a single month’s report, but the good December CPI report follows several months in which inflation has slowed sharply from the pace earlier in the year. All the evidence suggests that the economy is still growing at solid pace. (The latest projection for the fourth quarter from the Atlanta Fed’s GDPNow is 4.1 percent.)

It looks like the Fed has largely accomplished its mission of taming inflation, without bringing on a recession. Plenty of things can mess up this picture, like another surge of Covid or an escalation of the war in Ukraine, but for now, the economy is looking very good.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The media have been hyping inflation pretty much from the day President Biden took office. Today, we got great news on this front from a Consumer Price Index (CPI) report showing that overall inflation fell 0.1 percent in December. This is the 6th straight month where the overall CPI showed low inflation. While there are still grounds for concern, the picture looks pretty damn good at this point.

However, the media is not prepared to give up its inflation hysteria so quickly. The New York Times was on the job, raising some reasonable warning signs, then adding:

“Airline prices fell in December but remained nearly 29 percent higher compared with a year ago.”

While a 29 percent year over year increase might sound pretty scary, it’s actually not very scary to anyone who follows the data. Airline prices plummeted at the start of the pandemic, because people were not flying. They then bounced back more or less to where they had been before the pandemic. Here’s the picture.

CPI Index for Airfares: 2012 to 2022

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics.

The CPI index for airfares in December was 0.7 percent higher than its level in February of 2020. That is probably not the sort of price increase that will get the Fed or anyone else too worried about inflation.

The media have been hyping inflation pretty much from the day President Biden took office. Today, we got great news on this front from a Consumer Price Index (CPI) report showing that overall inflation fell 0.1 percent in December. This is the 6th straight month where the overall CPI showed low inflation. While there are still grounds for concern, the picture looks pretty damn good at this point.

However, the media is not prepared to give up its inflation hysteria so quickly. The New York Times was on the job, raising some reasonable warning signs, then adding:

“Airline prices fell in December but remained nearly 29 percent higher compared with a year ago.”

While a 29 percent year over year increase might sound pretty scary, it’s actually not very scary to anyone who follows the data. Airline prices plummeted at the start of the pandemic, because people were not flying. They then bounced back more or less to where they had been before the pandemic. Here’s the picture.

CPI Index for Airfares: 2012 to 2022

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics.

The CPI index for airfares in December was 0.7 percent higher than its level in February of 2020. That is probably not the sort of price increase that will get the Fed or anyone else too worried about inflation.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Everyone who carefully follows the news about the economy knows that we are in the middle of the Second Great Depression. On the other hand, those who read less news, but deal with things like jobs, wages, and bills probably think the economy is pretty damn good. We got more evidence on the pretty damn good side with the December jobs report and other economic data released in the last week.

The most important part of the jobs report was the drop in the unemployment rate to 3.5 percent. This equals the lowest rate in more than half a century. While many in the media insist that only elite intellectual types care about jobs, not ordinary workers, since the ability to pay for food, rent, and other bills is tightly linked to having a job, it seems that at least some workers might care about being able to work.

For these people, the tight labor market we have seen as the economy recovered from the pandemic recession is really good news. Not only do people have jobs, but the strong labor market means they can quit bad jobs. If the pay is low, the working conditions are bad, the boss is a jerk, workers can go elsewhere.

And, they are choosing to do so in large numbers. In November, the most recent month for which we have data, 2.7 percent of all workers, 4.2 million people, quit their job. This is near the record high of 3.0 percent reported at the end of 2021, and still above the highs reached before the pandemic and at the end of the 1990s boom.

The ability to quit bad jobs has predictably led to rising wages. Employers must raise pay to attract and retain workers. Real wages were dropping at the end of 2021 and the first half of 2022, as inflation outpaced wage growth, but as inflation slowed in the last half year, real wages have been rising at a healthy pace.

From June to November, the real average hourly wage has increased by 0.9 percent, a 2.2 percent annual rate. (We don’t have December price data yet.) Workers lower down the pay scale have done even better. The real average hourly wage for production and non-supervisory workers, a category that excludes managers and other highly paid workers, has risen by 1.4 percent since June, a 3.3 percent annual rate of increase. In the hotel and restaurant sectors, real pay has risen by 1.8 percent since June, a 4.4 percent annual rate of increase.

These real pay gains follow declines in 2021 and first half of 2022, but for many workers pay is already above the pre-pandemic level. For production and non-supervisory workers, the real average hourly wage is 0.3 percent above the February, 2020 level. For production and non-supervisory workers in the hotel and restaurant sectors real pay is up by 4.7 percent. The overall average for all workers is only down by 0.3 percent, a gap that will likely be largely eliminated by the wage growth reported for December.

While we may still have problems with inflation going forward, the sharp slowing in recent months was an unexpected surprise. We saw gas prices fall most of the way back to pre-pandemic levels. Many of the items where prices rose sharply due to supply chain problems, like appliances and furniture, are now seeing rapid drops in prices. Rents, which are a huge factor in the Consumer Price Index (CPI) and people’s budgets, have slowed sharply and are now falling in many areas. It will be several months before this slowing shows up in the CPI because of its methodology for measuring rental inflation, but based on private indexes of marketed housing units, we can be certain we will see rents rising much more slowly soon.

In short, there are good reasons for believing that we will see much slower inflation going forward. If we continue to see moderate nominal wage growth in 2023, that will translate into a healthy pace of real wage growth.

Homeownership

Also, contrary to what is widely reported, we had a largely positive picture on housing in the last three years. While current mortgage rates are pricing many people out of the market, homeownership did rise rapidly since the pandemic

The overall homeownership rate increased by 1.0 percentage point from the fourth quarter of 2019 to the third quarter of 2022. For Blacks, it rose by 1.2 percentage points, from 44.0 percent to 45.2 percent. For young people it rose by 1.7 percentage points, from 37.6 percent to 39.3 percent. For lower income households it rose by 1.3 percentage points from 51.4 percent to 52.7 percent.

It is striking that this rise in homeownership, especially for the most disadvantaged groups, is 180 degrees at odds with what is being reported in the media. These data come from the Census Bureau, which is generally considered an authoritative source. Nonetheless, the media have insisted that this has been a period in which young people, minorities, and low-income households have faced extraordinary difficulties in buying houses.

Income Growth

The media have also frequently told us that people are being forced to dip into their savings and that the saving rate is now at a record low. While the saving rate has fallen sharply in the last year, a major factor is that people have sold stock at large gains and are now paying capital gains taxes on these gains. Capital gains do not count as income, but the taxes paid on these gains are deducted from income in the national accounts, thereby lowering the saving rate. It’s not clear that people who sold stock at a gain, and then pay tax on that gain, are suffering severe financial hardship.

We also have the story of rapidly rising credit card debt. This has been presented as another indication of financial hardship. There actually is a simple and very different story. In 2020 and 2021, tens of millions of homeowners took advantage of extraordinarily low mortgage rates to refinance their homes. When they refinanced, they often would borrow more than their original mortgage to pay for various expenses they might be facing.

The Fed’s rate hikes have largely put an end to refinancing, including cash-out refinancing. With this channel closed to households, people that formerly would have looked to borrow by refinancing mortgage are instead turning to credit cards. This is hardly a crisis. Furthermore, tens of millions of families that were paying thousands more in mortgage interest, now have additional money to spend or save. This is not reflected in aggregate data.

It’s also worth noting one reason that inflation may have left many people strapped: the cost-of-living adjustments for Social Security are only paid once a year. This meant the checks beneficiaries were getting could buy around 7.0 percent less in December than they had the start of the year. However, Social Security beneficiaries are seeing an 8.7 percent increase in the size of their checks this month. That should make life considerably easier for tens of millions of retirees, and also modestly boost the saving rate.

Productivity Growth and Working from Home

Other bright spots in the economy include the return of healthy productivity growth and the huge increase in the number of people working from home. We saw two quarters of negative productivity growth in the first half of last year.

Productivity growth is poorly measured and highly erratic, but there seems little doubt that productivity growth was very poor in the first and second quarters of 2022. This added to the inflationary pressure that businesses were seeing.

This situation was reversed in the third quarter, with productivity growth coming in at close to 1.0 percent, roughly in line with the pre-pandemic trend. It looks like productivity growth will be even better in fourth quarter. GDP growth is now projected to be well over 3.0 percent, while payroll hours grew at just a 1.0 percent annual rate, implying a productivity growth rate close to 2.0 percent. This would be great news if it can be sustained, but as always, a single quarter’s data has to be viewed with great caution.

The other big positive in the economic picture is the huge increase in the number of people working from home. One recent paper estimated that 30 percent of all workdays are now remote, up from around 10 percent before the pandemic. While that number may prove somewhat high, it is clear that tens of millions of workers are now saving thousands a year on commuting costs and hundreds of hours formerly spent commuting. That is also a huge deal which is not picked up in our national accounts.

If the Economy Is Great, Why Do People Say They Think It Is Awful?

I’m not going to try to answer that one, other than to note that there has been a “horrible economy” echo chamber in the media, where facts have often been distorted or ignored altogether. I don’t know if that explains why so many people say they think the economy is bad, I’m an economist, not a social psychologist.

I will say that people are not acting like they think the economy is bad. They are buying huge amounts of big-ticket items like appliances and furniture, and until very recently houses. They are also going out to restaurants at a higher rate than before the pandemic. This is not behavior we would expect from people who feel their economic prospects are bleak.

To be clear, there are tens of millions of people who are struggling. Many can’t pay the rent, buy decent food and clothes for their kids, or pay for needed medicine or medical care. That is a horrible story, but this unfortunately is true even in the best of economic times. Until we adopt policies to protect people facing severe hardship we will have tens of millions of people struggling to get the necessities of life.

But this is not the horrible economy story the media is telling us. That is one that is suppose to apply to people higher up the income ladder. And, thankfully that story only exists in the media’s reporting, not in the economic data.

Everyone who carefully follows the news about the economy knows that we are in the middle of the Second Great Depression. On the other hand, those who read less news, but deal with things like jobs, wages, and bills probably think the economy is pretty damn good. We got more evidence on the pretty damn good side with the December jobs report and other economic data released in the last week.

The most important part of the jobs report was the drop in the unemployment rate to 3.5 percent. This equals the lowest rate in more than half a century. While many in the media insist that only elite intellectual types care about jobs, not ordinary workers, since the ability to pay for food, rent, and other bills is tightly linked to having a job, it seems that at least some workers might care about being able to work.

For these people, the tight labor market we have seen as the economy recovered from the pandemic recession is really good news. Not only do people have jobs, but the strong labor market means they can quit bad jobs. If the pay is low, the working conditions are bad, the boss is a jerk, workers can go elsewhere.

And, they are choosing to do so in large numbers. In November, the most recent month for which we have data, 2.7 percent of all workers, 4.2 million people, quit their job. This is near the record high of 3.0 percent reported at the end of 2021, and still above the highs reached before the pandemic and at the end of the 1990s boom.

The ability to quit bad jobs has predictably led to rising wages. Employers must raise pay to attract and retain workers. Real wages were dropping at the end of 2021 and the first half of 2022, as inflation outpaced wage growth, but as inflation slowed in the last half year, real wages have been rising at a healthy pace.

From June to November, the real average hourly wage has increased by 0.9 percent, a 2.2 percent annual rate. (We don’t have December price data yet.) Workers lower down the pay scale have done even better. The real average hourly wage for production and non-supervisory workers, a category that excludes managers and other highly paid workers, has risen by 1.4 percent since June, a 3.3 percent annual rate of increase. In the hotel and restaurant sectors, real pay has risen by 1.8 percent since June, a 4.4 percent annual rate of increase.