The New York Times had an article on the prospects for investment in clean energy if Donald Trump gets back in the White House. At one point the piece quotes Senator John Barrasso, a Republican from Wyoming, on the tax credits for electric vehicles:

“The electric vehicle tax credit benefits the wealthiest of Americans and costs hardworking American taxpayers billions of dollars, …”

It would have been useful to point out that individuals with an income above $150,000 and couples with income above $300,000 are not eligible for the tax credits. In other words, the senator’s charge that the tax credits benefit the wealthy is not true. New York Times readers should know this.

The New York Times had an article on the prospects for investment in clean energy if Donald Trump gets back in the White House. At one point the piece quotes Senator John Barrasso, a Republican from Wyoming, on the tax credits for electric vehicles:

“The electric vehicle tax credit benefits the wealthiest of Americans and costs hardworking American taxpayers billions of dollars, …”

It would have been useful to point out that individuals with an income above $150,000 and couples with income above $300,000 are not eligible for the tax credits. In other words, the senator’s charge that the tax credits benefit the wealthy is not true. New York Times readers should know this.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

As a major proponent of global warming, Donald Trump apparently thinks it benefits him to be perceived as a savior of jobs in the coal industry. This is likely not because he can do much to protect the country’s remaining coal jobs, but it gives him an opportunity to appear to be supporting workers.

The Washington Post, which is owned and controlled by people who will pay lower taxes with Donald Trump back in the White House, seems anxious to help Trump in this effort. That is the most likely explanation for the article near the top of the home page on how the Democrats are facing problems in a coal county in Pennsylvania.

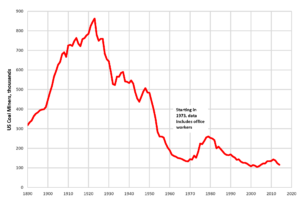

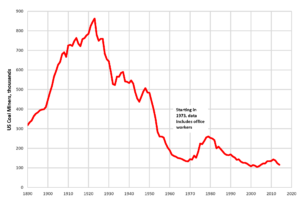

Before dealing with the specifics of the article, some background on coal and coal mining jobs is needed. The coal industry used to be a huge employer, both in Pennsylvania and across the country, as shown below.

Coal Industry Employment Since 1890

Source: US Census via Wikimedia.

At its peak in the middle of the 1920s, there were more than 850,000 people employed in coal mining. This was a time when total non farm employment was around 30 million, which means that coal mining would have accounted for roughly 2.8 percent of all jobs in the country.

Employment in the industry fell sharply over the next four decades, as oil and gas heating replaced coal to a large extent, and productivity growth reduced the need for miners. By the late 1960s, we were down to around 130,000 jobs in the coal industry, meaning we had lost over 700,000 jobs. At that point, total non farm employment was over 70 million, so the coal industry accounted for a bit less than 0.2 percent of total employment.

There was an uptick in employment in the industry in the 1970s, as the OPEC price increases led people to switch back to coal. Employment in the industry peaked at roughly 260,000 in 1979.

Employment in the industry then fell sharply over the next 20 years, sitting at just over 100,000 by 2000. The major factor was productivity growth, as strip mining replaced underground mining and also a switch back to oil and gas as their price fell back from the 1970s levels. Pollution regulation was also a factor in this decline, but a less important one. We were producing 50 percent more coal in 2000 than we had in 1979.

In the last dozen years, employment in the industry again fell sharply as natural gas displaced coal in many electric power plants. Currently, employment stands at a bit over 40,000, which is slightly less than 0.03 percent of total employment.

It’s clear that the general direction of employment in the coal industry is downward. Solar and wind power are already cheaper in most circumstances, with the costs declining rapidly. The cost of battery storage is also declining rapidly. Unless we impose massive taxes on clean energy and/or have huge subsidies for coal, we will be using much less coal in the years ahead.

This means that we will lose most or all of these 40,000 jobs in the not distant future. The question is, how big a deal is this?

Let’s say we lose the jobs over the course of a decade. That comes to 4,000 jobs a year. By comparison, in a healthy economy, 1,600,000 workers are laid off or fired from their jobs every month. This means that the 4,000 or so coal mining jobs we can expect to lose over the course of a year are less than one-tenth the number of people who would be losing their jobs in a typical day.

To be clear, the fact that lots of other people are losing their jobs doesn’t mean the job loss is any less traumatic for these coal miners. In many cases, this will be the best job they can ever hope to get. And in some small towns, the coal mine will be the main employer, so its loss will devastate the community. That is not something to be trivialized.

But we do need to keep it in perspective. Between 2000 and 2007 (before the Great Recession) we lost 3.5 million manufacturing jobs, largely due to trade. This far more massive loss of jobs (roughly 100 times as many) seemed to get less attention from the WaPo and other media outlets than the coal mining jobs now at risk.

Even taking this WaPo piece at face value, it’s difficult to see much of a case for its story. Pennsylvania is widely recognized as a swing state and a small number of votes can make a difference, but we should be clear on how small the number at stake here is likely to be.

Pennsylvania has 4,700 coal mining jobs as of May. Total employment in the state was 6.15 million, which means that the industry accounted for less than 0.08 percent of statewide employment.

The counties where coal is important are overwhelmingly white. Indiana County, which is the focus of the article is roughly 95 percent non-Hispanic white. Trump carried the rural white vote in 2020 by margins of close to two to one even in areas like rural Minnesota and Wisconsin, where the coal industry has never been an issue. That means that if Biden can somehow overcome anger over coal jobs, he would still likely lose these voters by a large margin.

Suppose that every coal mining job is associated with two votes and if Biden can somehow do the right thing by the miners (in their view) it will reduce Biden’s losing margin among this group by 10 percentage points. That would translate into 940 additional votes for Biden. This is almost certainly a large exaggeration of what is plausibly at stake since many of these people will not vote and 10 percentage points would be a very large shift.

In 2020, Biden’s margin of victory in the state was 1.2 percentage points or 80,000 votes. In this context, the 940 votes plausibly at issue in coal country could matter, but it’s not likely.

What could have a much greater effect is if the Washington Post and other major media outlets can keep up a drumbeat that Biden is indifferent to the plight of ordinary workers. That is how this article is best understood.

As a major proponent of global warming, Donald Trump apparently thinks it benefits him to be perceived as a savior of jobs in the coal industry. This is likely not because he can do much to protect the country’s remaining coal jobs, but it gives him an opportunity to appear to be supporting workers.

The Washington Post, which is owned and controlled by people who will pay lower taxes with Donald Trump back in the White House, seems anxious to help Trump in this effort. That is the most likely explanation for the article near the top of the home page on how the Democrats are facing problems in a coal county in Pennsylvania.

Before dealing with the specifics of the article, some background on coal and coal mining jobs is needed. The coal industry used to be a huge employer, both in Pennsylvania and across the country, as shown below.

Coal Industry Employment Since 1890

Source: US Census via Wikimedia.

At its peak in the middle of the 1920s, there were more than 850,000 people employed in coal mining. This was a time when total non farm employment was around 30 million, which means that coal mining would have accounted for roughly 2.8 percent of all jobs in the country.

Employment in the industry fell sharply over the next four decades, as oil and gas heating replaced coal to a large extent, and productivity growth reduced the need for miners. By the late 1960s, we were down to around 130,000 jobs in the coal industry, meaning we had lost over 700,000 jobs. At that point, total non farm employment was over 70 million, so the coal industry accounted for a bit less than 0.2 percent of total employment.

There was an uptick in employment in the industry in the 1970s, as the OPEC price increases led people to switch back to coal. Employment in the industry peaked at roughly 260,000 in 1979.

Employment in the industry then fell sharply over the next 20 years, sitting at just over 100,000 by 2000. The major factor was productivity growth, as strip mining replaced underground mining and also a switch back to oil and gas as their price fell back from the 1970s levels. Pollution regulation was also a factor in this decline, but a less important one. We were producing 50 percent more coal in 2000 than we had in 1979.

In the last dozen years, employment in the industry again fell sharply as natural gas displaced coal in many electric power plants. Currently, employment stands at a bit over 40,000, which is slightly less than 0.03 percent of total employment.

It’s clear that the general direction of employment in the coal industry is downward. Solar and wind power are already cheaper in most circumstances, with the costs declining rapidly. The cost of battery storage is also declining rapidly. Unless we impose massive taxes on clean energy and/or have huge subsidies for coal, we will be using much less coal in the years ahead.

This means that we will lose most or all of these 40,000 jobs in the not distant future. The question is, how big a deal is this?

Let’s say we lose the jobs over the course of a decade. That comes to 4,000 jobs a year. By comparison, in a healthy economy, 1,600,000 workers are laid off or fired from their jobs every month. This means that the 4,000 or so coal mining jobs we can expect to lose over the course of a year are less than one-tenth the number of people who would be losing their jobs in a typical day.

To be clear, the fact that lots of other people are losing their jobs doesn’t mean the job loss is any less traumatic for these coal miners. In many cases, this will be the best job they can ever hope to get. And in some small towns, the coal mine will be the main employer, so its loss will devastate the community. That is not something to be trivialized.

But we do need to keep it in perspective. Between 2000 and 2007 (before the Great Recession) we lost 3.5 million manufacturing jobs, largely due to trade. This far more massive loss of jobs (roughly 100 times as many) seemed to get less attention from the WaPo and other media outlets than the coal mining jobs now at risk.

Even taking this WaPo piece at face value, it’s difficult to see much of a case for its story. Pennsylvania is widely recognized as a swing state and a small number of votes can make a difference, but we should be clear on how small the number at stake here is likely to be.

Pennsylvania has 4,700 coal mining jobs as of May. Total employment in the state was 6.15 million, which means that the industry accounted for less than 0.08 percent of statewide employment.

The counties where coal is important are overwhelmingly white. Indiana County, which is the focus of the article is roughly 95 percent non-Hispanic white. Trump carried the rural white vote in 2020 by margins of close to two to one even in areas like rural Minnesota and Wisconsin, where the coal industry has never been an issue. That means that if Biden can somehow overcome anger over coal jobs, he would still likely lose these voters by a large margin.

Suppose that every coal mining job is associated with two votes and if Biden can somehow do the right thing by the miners (in their view) it will reduce Biden’s losing margin among this group by 10 percentage points. That would translate into 940 additional votes for Biden. This is almost certainly a large exaggeration of what is plausibly at stake since many of these people will not vote and 10 percentage points would be a very large shift.

In 2020, Biden’s margin of victory in the state was 1.2 percentage points or 80,000 votes. In this context, the 940 votes plausibly at issue in coal country could matter, but it’s not likely.

What could have a much greater effect is if the Washington Post and other major media outlets can keep up a drumbeat that Biden is indifferent to the plight of ordinary workers. That is how this article is best understood.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Even though we have had the longest streak of below 4.0 percent unemployment in 70 years, and real wages are rising, especially at the bottom end of the wage distribution, the major media outlets insist the economy is terrible. The Washington Post is setting the pace with the lead story on its homepage headlined “Millennials had it bad financially, but Gen Z may have it worse.”

This one gets pretty creative in telling us how Gen Z has it awful. My favorite is a graph that shows that recent college grads now have a higher unemployment rate than the overall average for all workers. Yeah, that is really horrible. Think of how young college grads must be suffering because older people and those who didn’t graduate college have jobs. Can you feel the hardship?

If we look at the graph, we see that the unemployment rate for recent college grads is actually relatively low at 4.3 percent. This is lower than it was for much of the 1990s, the 2000s, and most of the decade before the pandemic. So, does the Post want us to believe that young college grads are suffering not because they face high unemployment, but because other workers face low unemployment?

The other part of this story that the Post chose not to point out is that, given the relatively low unemployment rate for young people as a whole, the slightly higher rate for college grads means that those without college degrees have unusually low rates. Since most young people don’t have college degrees, this sounds like a good story for Gen Z.

The piece also features a graph showing that inflation adjusted insurance costs and housing costs have outpaced real wage growth, while real food prices have roughly kept even. There are a few points to be made on this graph.

First, it is not clear what housing index they are using. The graph shows real housing costs rising by 115 percent since 1985. The CPI rent index shows real rent increasing by less than 30 percent over this period.

The second point is that it shows real auto insurance costs rising by 145 percent over this period. This is a gross measure of what people pay for insurance, it does not subtract out what they get paid back in claims. The Commerce Department uses a net measure, which shows a still substantial, but considerably smaller 63 percent real increase.

Much of the reason that insurance premiums have gone up so much is that insurers are seeing more and larger claims. Some of this is due to more expensive cars and some of it is due to more climate-related claims, like vehicles being destroyed by fires or flooding. Anyhow, if we have to pay more for insurance because climate change is imposing more damage, that is probably not inflation as we conventionally think of it.

The final point is that the graph shows real wages have risen (as in up) by 33 percent since 1985. Remember, this is a piece that is telling us how bad young people have it today compared to their elders, but it shows us that their real wages are one-third higher than what people got four decades ago.

I would be happy to support the argument that we should have seen faster wage growth. That would have been the case if there had not been so much upward redistribution over the last four decades, but let’s not get caught up in the which-way-is-up problem. Higher real wages mean, as a first approximation, people are better off. That is the wrong direction for the Washington Post’s suffering Gen Z story.

One final point, while the piece spends considerable time on the debt of Generation Z, it chose not to mention President Biden’s income-driven repayment plan for student loan debt. Under this plan, a single person earning less than $32k a year would pay nothing back on their loans and a person earning $40k a year would pay just $60 a month. This should ensure that student loan debt is not a major burden for most borrowers.

For some reason, reporters writing on student debt almost never seem to mention the income-driven repayment plan. This is a bit mind-boggling, but I suppose if you’re trying to pitch the suffering Gen Z story, it is a convenient fact to ignore.

Even though we have had the longest streak of below 4.0 percent unemployment in 70 years, and real wages are rising, especially at the bottom end of the wage distribution, the major media outlets insist the economy is terrible. The Washington Post is setting the pace with the lead story on its homepage headlined “Millennials had it bad financially, but Gen Z may have it worse.”

This one gets pretty creative in telling us how Gen Z has it awful. My favorite is a graph that shows that recent college grads now have a higher unemployment rate than the overall average for all workers. Yeah, that is really horrible. Think of how young college grads must be suffering because older people and those who didn’t graduate college have jobs. Can you feel the hardship?

If we look at the graph, we see that the unemployment rate for recent college grads is actually relatively low at 4.3 percent. This is lower than it was for much of the 1990s, the 2000s, and most of the decade before the pandemic. So, does the Post want us to believe that young college grads are suffering not because they face high unemployment, but because other workers face low unemployment?

The other part of this story that the Post chose not to point out is that, given the relatively low unemployment rate for young people as a whole, the slightly higher rate for college grads means that those without college degrees have unusually low rates. Since most young people don’t have college degrees, this sounds like a good story for Gen Z.

The piece also features a graph showing that inflation adjusted insurance costs and housing costs have outpaced real wage growth, while real food prices have roughly kept even. There are a few points to be made on this graph.

First, it is not clear what housing index they are using. The graph shows real housing costs rising by 115 percent since 1985. The CPI rent index shows real rent increasing by less than 30 percent over this period.

The second point is that it shows real auto insurance costs rising by 145 percent over this period. This is a gross measure of what people pay for insurance, it does not subtract out what they get paid back in claims. The Commerce Department uses a net measure, which shows a still substantial, but considerably smaller 63 percent real increase.

Much of the reason that insurance premiums have gone up so much is that insurers are seeing more and larger claims. Some of this is due to more expensive cars and some of it is due to more climate-related claims, like vehicles being destroyed by fires or flooding. Anyhow, if we have to pay more for insurance because climate change is imposing more damage, that is probably not inflation as we conventionally think of it.

The final point is that the graph shows real wages have risen (as in up) by 33 percent since 1985. Remember, this is a piece that is telling us how bad young people have it today compared to their elders, but it shows us that their real wages are one-third higher than what people got four decades ago.

I would be happy to support the argument that we should have seen faster wage growth. That would have been the case if there had not been so much upward redistribution over the last four decades, but let’s not get caught up in the which-way-is-up problem. Higher real wages mean, as a first approximation, people are better off. That is the wrong direction for the Washington Post’s suffering Gen Z story.

One final point, while the piece spends considerable time on the debt of Generation Z, it chose not to mention President Biden’s income-driven repayment plan for student loan debt. Under this plan, a single person earning less than $32k a year would pay nothing back on their loans and a person earning $40k a year would pay just $60 a month. This should ensure that student loan debt is not a major burden for most borrowers.

For some reason, reporters writing on student debt almost never seem to mention the income-driven repayment plan. This is a bit mind-boggling, but I suppose if you’re trying to pitch the suffering Gen Z story, it is a convenient fact to ignore.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The media have told us endlessly how people can no longer afford things due to higher prices and the fact that wages have risen more doesn’t matter. I wouldn’t want to disagree with the experts, but suppose we just did a little calculation about how much time it takes a typical worker to earn enough money to buy a gallon of gas.

Here’s the picture going back a decade.

This takes the price of a gallon of gas and divides it by the average hourly earnings for production and non-supervisory workers. This is a category that covers roughly 80 percent of the workforce, but excludes most high-end earners like managers, professionals, and Wall Street types. This means that it cannot be skewed by the big bucks going to the top.

As can be seen, gas prices did jump a lot relative to wages in the spring of 2022, following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. At the peak, in June of 2022, it took 0.179 hours of work (10.7 minutes) to pay for a gallon of gas.

That was more than twice as high as low hits during the pandemic when the economy was shut down, although it was not that high by historical standards. Gas cost more than 0.20 hours of work (12 minutes) at points in 2011 and it peaked at 0.224 hours of work (13.5 minutes) in July of 2008.

But June 2022 was two years ago, and the oil markets have largely stabilized since then. The most recent figure is 0.12 hours (7.2 minutes). That’s still a lot higher than when the economy was shut down. (Donald Trump seems to think those were glory days – gas was less than $2.00 a gallon, but we couldn’t leave our homes.) But the current 0.12 hours cost of gas doesn’t look bad compared to prior periods.

For example, in 2018, it took as much as 0.128 hours (7.7 minutes) to pay for a gallon of gas. In 2019 gas peaked at 0.122 hours (7.3 minutes) of labor in May. It’s understandable people would want cheaper gas, just like they want higher pay. But the reality is that it is not especially high by historical standards, including what we saw in the recent past.

The spread of electric cars in the U.S. and elsewhere is likely to send gas prices lower in the years ahead. Electric car buyers will of course not especially care about gas prices, but more people buying electric cars will mean cheaper gas prices for those who don’t. (No, that’s not especially fair, just the reality.) Anyhow, the basic story is gas prices are actually pretty low today compared to what people earn, but that doesn’t mean the media should not yell about gas being unaffordable.

The media have told us endlessly how people can no longer afford things due to higher prices and the fact that wages have risen more doesn’t matter. I wouldn’t want to disagree with the experts, but suppose we just did a little calculation about how much time it takes a typical worker to earn enough money to buy a gallon of gas.

Here’s the picture going back a decade.

This takes the price of a gallon of gas and divides it by the average hourly earnings for production and non-supervisory workers. This is a category that covers roughly 80 percent of the workforce, but excludes most high-end earners like managers, professionals, and Wall Street types. This means that it cannot be skewed by the big bucks going to the top.

As can be seen, gas prices did jump a lot relative to wages in the spring of 2022, following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. At the peak, in June of 2022, it took 0.179 hours of work (10.7 minutes) to pay for a gallon of gas.

That was more than twice as high as low hits during the pandemic when the economy was shut down, although it was not that high by historical standards. Gas cost more than 0.20 hours of work (12 minutes) at points in 2011 and it peaked at 0.224 hours of work (13.5 minutes) in July of 2008.

But June 2022 was two years ago, and the oil markets have largely stabilized since then. The most recent figure is 0.12 hours (7.2 minutes). That’s still a lot higher than when the economy was shut down. (Donald Trump seems to think those were glory days – gas was less than $2.00 a gallon, but we couldn’t leave our homes.) But the current 0.12 hours cost of gas doesn’t look bad compared to prior periods.

For example, in 2018, it took as much as 0.128 hours (7.7 minutes) to pay for a gallon of gas. In 2019 gas peaked at 0.122 hours (7.3 minutes) of labor in May. It’s understandable people would want cheaper gas, just like they want higher pay. But the reality is that it is not especially high by historical standards, including what we saw in the recent past.

The spread of electric cars in the U.S. and elsewhere is likely to send gas prices lower in the years ahead. Electric car buyers will of course not especially care about gas prices, but more people buying electric cars will mean cheaper gas prices for those who don’t. (No, that’s not especially fair, just the reality.) Anyhow, the basic story is gas prices are actually pretty low today compared to what people earn, but that doesn’t mean the media should not yell about gas being unaffordable.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

That’s what readers must conclude after reading this Washington Post’s piece on President Biden’s plans to increase corporate taxes and taxes on the rich. At one point, the piece reports the response to these plans from Rep. Steven Scalise (R-La), the second-ranking Republican in the House:

“He tries to act like it’s not going to affect certain people, but when you raise taxes, it hits everybody, especially low-income families. Look at what his energy policies have done. The people hit the hardest are low-income families paying higher gas prices, paying more at the grocery store and more for their household electricity bills all because of bad Biden policies.”

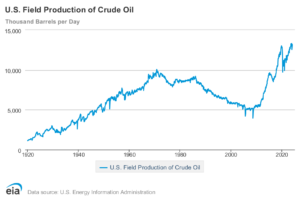

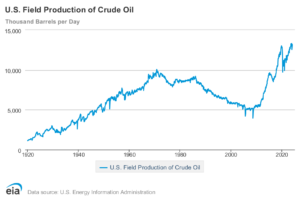

While it then turns back to people discussing the merits of Biden’s proposals for taxing corporations and the rich, it neglects to point out that Biden’s energy policies have resulted in record levels of oil production.

This is a dubious accomplishment for those of us concerned about global warming, but it points out that Scalise’s complaint that Biden’s policies have led to higher gas prices is a lie. The rise in world oil prices, and the resulting increase in gas prices, is primarily due to the robust recovery from the pandemic recession, not Biden’s energy policies.

That’s what readers must conclude after reading this Washington Post’s piece on President Biden’s plans to increase corporate taxes and taxes on the rich. At one point, the piece reports the response to these plans from Rep. Steven Scalise (R-La), the second-ranking Republican in the House:

“He tries to act like it’s not going to affect certain people, but when you raise taxes, it hits everybody, especially low-income families. Look at what his energy policies have done. The people hit the hardest are low-income families paying higher gas prices, paying more at the grocery store and more for their household electricity bills all because of bad Biden policies.”

While it then turns back to people discussing the merits of Biden’s proposals for taxing corporations and the rich, it neglects to point out that Biden’s energy policies have resulted in record levels of oil production.

This is a dubious accomplishment for those of us concerned about global warming, but it points out that Scalise’s complaint that Biden’s policies have led to higher gas prices is a lie. The rise in world oil prices, and the resulting increase in gas prices, is primarily due to the robust recovery from the pandemic recession, not Biden’s energy policies.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

As we enter the fourth decade of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), and now its successor, the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA), it is worth taking a quick look at the track record. Folks who can remember back to the debate around the agreement might recall that it was supposed to spur growth in Mexico and allow it to close the income gap with the United States. It hasn’t turned out that way.

The graph below shows the ratio of per capita GDP in Mexico to per capita GDP in the United States going back to 1980.

Source: International Monetary Fund.

At the start of this period, Mexico’s per capita GDP was well over half of the per capita GDP in the United States. It then fell sharply over the course of the decade, bottoming out at 38.6 percent in 1989.

There is a simple story here. The price of oil collapsed. Mexico’s economy was booming in the late 1970s as the Iranian revolution sent world oil prices soaring. As oil producing nations sought to ramp up production and the world economy went into recession, oil prices plummeted. Countries like Mexico, which were heavily dependent on oil exports, took a huge hit.

By 1990 the economy had turned the corner and was making at least moderate progress relative to the US, but that ended with a currency crisis at the start of 1994. While the crisis was at most indirectly related to NAFTA, Mexico never recovered the lost ground and continued on a downward relative course.

The ratio of Mexico’s GDP to US GDP had fallen to 35.9 percent by the 10th anniversary of NAFTA in 2004. It dropped further to 34.4 percent by 2014 on the 20th anniversary. The IMF’s projection for 2024 puts Mexico’s per capita GDP at just 30.4 percent of US GDP. Its per capita income grew by 20.3 percent over the last 30 years, an average annual rate of just over 0.6 percent.

GDP growth is not everything. If income is more evenly distributed or the government has prioritized meeting social needs like education and health care, then income gains may understate the benefits to society. But that story does not seem likely with Mexico. In any case, the promise of NAFTA that it would lead to convergence between Mexico and the two richer countries in the pact clearly has not been fulfilled.

As we enter the fourth decade of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), and now its successor, the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA), it is worth taking a quick look at the track record. Folks who can remember back to the debate around the agreement might recall that it was supposed to spur growth in Mexico and allow it to close the income gap with the United States. It hasn’t turned out that way.

The graph below shows the ratio of per capita GDP in Mexico to per capita GDP in the United States going back to 1980.

Source: International Monetary Fund.

At the start of this period, Mexico’s per capita GDP was well over half of the per capita GDP in the United States. It then fell sharply over the course of the decade, bottoming out at 38.6 percent in 1989.

There is a simple story here. The price of oil collapsed. Mexico’s economy was booming in the late 1970s as the Iranian revolution sent world oil prices soaring. As oil producing nations sought to ramp up production and the world economy went into recession, oil prices plummeted. Countries like Mexico, which were heavily dependent on oil exports, took a huge hit.

By 1990 the economy had turned the corner and was making at least moderate progress relative to the US, but that ended with a currency crisis at the start of 1994. While the crisis was at most indirectly related to NAFTA, Mexico never recovered the lost ground and continued on a downward relative course.

The ratio of Mexico’s GDP to US GDP had fallen to 35.9 percent by the 10th anniversary of NAFTA in 2004. It dropped further to 34.4 percent by 2014 on the 20th anniversary. The IMF’s projection for 2024 puts Mexico’s per capita GDP at just 30.4 percent of US GDP. Its per capita income grew by 20.3 percent over the last 30 years, an average annual rate of just over 0.6 percent.

GDP growth is not everything. If income is more evenly distributed or the government has prioritized meeting social needs like education and health care, then income gains may understate the benefits to society. But that story does not seem likely with Mexico. In any case, the promise of NAFTA that it would lead to convergence between Mexico and the two richer countries in the pact clearly has not been fulfilled.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Everyone knows that the Washington Post is owned and controlled by people who will pay lower taxes if Donald Trump gets back into the White House, but couldn’t it at least pretend to be a newspaper?

In a piece discussing the political debate over electric vehicles, the Post told readers: “Trump has vowed to roll back Biden’s electric vehicle efforts and warned ‘you’re not going to be able to sell those cars’ if he becomes president.

…

“It is an easy attack line for Trump, however, who called the Biden regulations ‘ridiculous’ in a recent meeting with oil industry executives who he brazenly asked to raise $1 billion for his campaign.

“At a rally in Las Vegas earlier this month, Trump went on a lengthy rant against electric-powered boats, saying he would have trouble knowing what to do if the boat was sinking in shark-infested waters. ‘Do I get electrocuted if the boat is sinking, water goes over the battery, the boat is sinking? Do I stay on top of the boat and get electrocuted, or do I jump over by the shark and not get electrocuted?’ he asked.

“’I’ll take electrocution every single time,’ he said. ‘I’m not getting near the shark.’”

Contrary to what the Post tells readers, it really should not be “an easy attack line” for Trump. He is on record saying that there will be a “bloodbath” in the auto industry if we allow Chinese EVs to be sold in the United States without high taxes.

This might be too difficult for Donald Trump to understand, but ordinary people can figure out that you would not need high taxes to keep people from buying cars they don’t want. Donald Trump is making the absurd argument that people don’t want to buy EVs, but we need very high taxes to keep them from buying them.

That sort of contradiction on a major political issue would be highly embarrassing for a presidential candidate, if the media could find out about it.

Everyone knows that the Washington Post is owned and controlled by people who will pay lower taxes if Donald Trump gets back into the White House, but couldn’t it at least pretend to be a newspaper?

In a piece discussing the political debate over electric vehicles, the Post told readers: “Trump has vowed to roll back Biden’s electric vehicle efforts and warned ‘you’re not going to be able to sell those cars’ if he becomes president.

…

“It is an easy attack line for Trump, however, who called the Biden regulations ‘ridiculous’ in a recent meeting with oil industry executives who he brazenly asked to raise $1 billion for his campaign.

“At a rally in Las Vegas earlier this month, Trump went on a lengthy rant against electric-powered boats, saying he would have trouble knowing what to do if the boat was sinking in shark-infested waters. ‘Do I get electrocuted if the boat is sinking, water goes over the battery, the boat is sinking? Do I stay on top of the boat and get electrocuted, or do I jump over by the shark and not get electrocuted?’ he asked.

“’I’ll take electrocution every single time,’ he said. ‘I’m not getting near the shark.’”

Contrary to what the Post tells readers, it really should not be “an easy attack line” for Trump. He is on record saying that there will be a “bloodbath” in the auto industry if we allow Chinese EVs to be sold in the United States without high taxes.

This might be too difficult for Donald Trump to understand, but ordinary people can figure out that you would not need high taxes to keep people from buying cars they don’t want. Donald Trump is making the absurd argument that people don’t want to buy EVs, but we need very high taxes to keep them from buying them.

That sort of contradiction on a major political issue would be highly embarrassing for a presidential candidate, if the media could find out about it.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The belief in free-market fundamentalism runs very deep. When I say that, I don’t mean that support for the concept runs deep, I mean the belief that we had been pursuing free-market policies in the years before the Trump and Biden presidency runs very deep. I was reminded of this fact in a New York Times column by Farah Stockman, touting the development of a new post-free-market fundamentalist paradigm.

To be clear, the period of so-called free-market fundamentalism was one in which we saw a massive upward redistribution of wealth and income as has been extensively documented in numerous studies. It is understandable that the people who are happy about this upward redistribution would like to attribute it to the natural workings of the market.

The story goes, yeah Elon Musk and Bill Gates are very rich, and lots of ordinary workers are kind of screwed, but shit happens. If we feel bad enough about it, we can toss some dimes to the left behind. After all, Bill Gates started a big foundation to help the world’s poor.

That’s a far more generous story for the rich than the reality. It was not just a case of “shit happens,” where the natural workings of the market gave them all the money. It was a story where they actively rigged the rules to ensure that a huge amount of money would be redistributed upward.

The place where I always begin is with government-granted patent and copyright monopolies. It is mind-boggling that serious people can think that these massive forms of government intervention are somehow the “free market.”

And to be clear, there is huge money at issue. In the case of prescription drugs alone the gap between the patent-protected prices we pay and the price drugs would sell for in a free market is likely more than $600 billion a year.

This is more than 2.2 percent of GDP. By comparison, after-tax corporate profits in 2023 were less than $2.7 trillion. And this $600 billion figure is just for drugs. Add in medical devices, software, computers, video games and all the other items where patents or copyrights account for a large share of the price, and we are almost certainly far over $1 trillion a year. Yet we are supposed to believe that this is just the free market here?

It is also important to recognize that we could use other mechanisms than these monopolies for supporting innovation and creative work. We can and do have direct public funding or tax credits in various forms. We can also make the patent and copyright protections we have shorter and weaker, rather than longer and stronger, as has been the case over the last half-century.

This is far from the only area where the government has played a huge role under “free-market fundamentalism.” While we were ostensibly pushing a free trade agenda, we did little or nothing to reduce the trade barriers that protect our most highly paid professionals, like doctors and dentists, from international competition.

As a result, these professionals are paid more than twice as much here as their counterparts in other wealthy countries. We would save close to $150 billion a year (more than $1000 per family) if we paid our doctors the same salaries they get in Germany or Canada.

Our policies were never about free trade. They were about selective protectionism, where we expose manufacturing workers to direct competition with low-paid workers in the developing world, but we protect our most highly-paid professionals from the same sort of competition.

Again, it’s not surprising that the winners from this policy would like to call it “free trade.” That sounds much better than structuring trade to make the rich richer. But why would opponents of this policy accept this dishonest terminology?

The UAW strike last fall highlighted the huge disparity in pay between the CEOs at the Big Three auto companies and the pay of top execs at the major auto companies in Europe and Japan. Our top execs get roughly four times the pay of their counterparts at European car companies and, in the extreme case, ten times as much as their pay at Japanese companies.

This gap in pay is not explained by differences in size and profitability. The European and Japanese car companies are every bit as big and profitable as the U.S. companies. They just have different rules of corporate governance that make it more difficult for the CEOs and other top executives to rip off the companies they work for. And rules of corporate governance are not set by the free market, they are set by governments.

The massive fortunes in the financial sector are only possible because the government has rigged the rules to encourage a bloated financial sector. If there was a tax on financial transactions, similar to the sales tax most of us pay when we buy food or clothes, the sector would be far smaller and there would be many fewer Wall Street millionaires and billionaires. The free market didn’t tell us to exempt the financial sector from the taxes most other sectors pay.

Similarly, tax rules, like the carried interest deduction, along with bankruptcy laws that are very favorable to corporate debtors, provide much of the basis for the fortunes earned by hedge fund and private equity partners. These were given to us by the lobbying of powerful interests, not the free market.

Facebook, X, TikTok, and other social media giants are able to thrive in large part because of their Section 230 protections. Here also Section 230 came to us from corporate lobbyists, not the free market.

It is hard to understand why we have this obsession in intellectual circles that we have been living through a long period of market fundamentalism. It is a lie and it should not be perpetuated, especially now that people are declaring its demise.

This is not just a semantic point. It speaks to the issue of how we want to structure the economy. If we fail to recognize that there is no such thing as a “free market,” then we are not thinking seriously about the economy.

The government always must structure the market. It is literally infinitely malleable. If we think of the options as government versus the free market, then we don’t understand what we are dealing with and it is likely to end badly.

(Yes, this is my book Rigged [it’s free]. There’s also the video version.)

The belief in free-market fundamentalism runs very deep. When I say that, I don’t mean that support for the concept runs deep, I mean the belief that we had been pursuing free-market policies in the years before the Trump and Biden presidency runs very deep. I was reminded of this fact in a New York Times column by Farah Stockman, touting the development of a new post-free-market fundamentalist paradigm.

To be clear, the period of so-called free-market fundamentalism was one in which we saw a massive upward redistribution of wealth and income as has been extensively documented in numerous studies. It is understandable that the people who are happy about this upward redistribution would like to attribute it to the natural workings of the market.

The story goes, yeah Elon Musk and Bill Gates are very rich, and lots of ordinary workers are kind of screwed, but shit happens. If we feel bad enough about it, we can toss some dimes to the left behind. After all, Bill Gates started a big foundation to help the world’s poor.

That’s a far more generous story for the rich than the reality. It was not just a case of “shit happens,” where the natural workings of the market gave them all the money. It was a story where they actively rigged the rules to ensure that a huge amount of money would be redistributed upward.

The place where I always begin is with government-granted patent and copyright monopolies. It is mind-boggling that serious people can think that these massive forms of government intervention are somehow the “free market.”

And to be clear, there is huge money at issue. In the case of prescription drugs alone the gap between the patent-protected prices we pay and the price drugs would sell for in a free market is likely more than $600 billion a year.

This is more than 2.2 percent of GDP. By comparison, after-tax corporate profits in 2023 were less than $2.7 trillion. And this $600 billion figure is just for drugs. Add in medical devices, software, computers, video games and all the other items where patents or copyrights account for a large share of the price, and we are almost certainly far over $1 trillion a year. Yet we are supposed to believe that this is just the free market here?

It is also important to recognize that we could use other mechanisms than these monopolies for supporting innovation and creative work. We can and do have direct public funding or tax credits in various forms. We can also make the patent and copyright protections we have shorter and weaker, rather than longer and stronger, as has been the case over the last half-century.

This is far from the only area where the government has played a huge role under “free-market fundamentalism.” While we were ostensibly pushing a free trade agenda, we did little or nothing to reduce the trade barriers that protect our most highly paid professionals, like doctors and dentists, from international competition.

As a result, these professionals are paid more than twice as much here as their counterparts in other wealthy countries. We would save close to $150 billion a year (more than $1000 per family) if we paid our doctors the same salaries they get in Germany or Canada.

Our policies were never about free trade. They were about selective protectionism, where we expose manufacturing workers to direct competition with low-paid workers in the developing world, but we protect our most highly-paid professionals from the same sort of competition.

Again, it’s not surprising that the winners from this policy would like to call it “free trade.” That sounds much better than structuring trade to make the rich richer. But why would opponents of this policy accept this dishonest terminology?

The UAW strike last fall highlighted the huge disparity in pay between the CEOs at the Big Three auto companies and the pay of top execs at the major auto companies in Europe and Japan. Our top execs get roughly four times the pay of their counterparts at European car companies and, in the extreme case, ten times as much as their pay at Japanese companies.

This gap in pay is not explained by differences in size and profitability. The European and Japanese car companies are every bit as big and profitable as the U.S. companies. They just have different rules of corporate governance that make it more difficult for the CEOs and other top executives to rip off the companies they work for. And rules of corporate governance are not set by the free market, they are set by governments.

The massive fortunes in the financial sector are only possible because the government has rigged the rules to encourage a bloated financial sector. If there was a tax on financial transactions, similar to the sales tax most of us pay when we buy food or clothes, the sector would be far smaller and there would be many fewer Wall Street millionaires and billionaires. The free market didn’t tell us to exempt the financial sector from the taxes most other sectors pay.

Similarly, tax rules, like the carried interest deduction, along with bankruptcy laws that are very favorable to corporate debtors, provide much of the basis for the fortunes earned by hedge fund and private equity partners. These were given to us by the lobbying of powerful interests, not the free market.

Facebook, X, TikTok, and other social media giants are able to thrive in large part because of their Section 230 protections. Here also Section 230 came to us from corporate lobbyists, not the free market.

It is hard to understand why we have this obsession in intellectual circles that we have been living through a long period of market fundamentalism. It is a lie and it should not be perpetuated, especially now that people are declaring its demise.

This is not just a semantic point. It speaks to the issue of how we want to structure the economy. If we fail to recognize that there is no such thing as a “free market,” then we are not thinking seriously about the economy.

The government always must structure the market. It is literally infinitely malleable. If we think of the options as government versus the free market, then we don’t understand what we are dealing with and it is likely to end badly.

(Yes, this is my book Rigged [it’s free]. There’s also the video version.)

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

If we wanted to know what the job market looks like for recent college graduates, we would probably start by looking at their unemployment/employment rates. On the other hand, if we wanted to try to make the labor market for recent college grads look bad, we could follow the Washington Post’s lead and look at the re-employment rates for college grads who report being unemployed.

While the latter statistic is interesting, it only tells us about the employment prospects for the roughly 4.0 percent of college grads who report being unemployed in any given month. It tells us nothing about the job prospects for the 96 percent of college grads in the labor market who have jobs.

As it turns out, the prospects for recent college grads who end up being unemployed are not very good. This is what the Washington Post chose to highlight in a piece headlined, “Degree? Yes. Job? Maybe Not Yet.”

The article starts out by talking about the re-employment rate for new entrants to the workforce and shows us that it is far lower than for more experienced workers. This is shown with a large graph.

Next in the piece we do get the employment rate for all young people, not just recent grads, which has fallen in recent months back to levels reached in 2016, after previously reaching levels that were close to pre-pandemic peaks.

It is only towards the bottom of the piece that we get the unemployment rate for recent grads (4.3 percent). This is up slightly from the 3.9 percent low hit in 2022, but still low by most standards and very comparable to the rates we saw just before the pandemic.

As a practical matter, it is hard to imagine that someone could look at a 4.3 percent unemployment rate and say college grads are having a hard time finding jobs. Oddly, this is the second time in two weeks we saw this re-employment rate for recent grads highlighted as meaning that college grads are having trouble getting jobs.

The market for recent college grads continues to look pretty good, but the market for bad news on the economy is red hot.

If we wanted to know what the job market looks like for recent college graduates, we would probably start by looking at their unemployment/employment rates. On the other hand, if we wanted to try to make the labor market for recent college grads look bad, we could follow the Washington Post’s lead and look at the re-employment rates for college grads who report being unemployed.

While the latter statistic is interesting, it only tells us about the employment prospects for the roughly 4.0 percent of college grads who report being unemployed in any given month. It tells us nothing about the job prospects for the 96 percent of college grads in the labor market who have jobs.

As it turns out, the prospects for recent college grads who end up being unemployed are not very good. This is what the Washington Post chose to highlight in a piece headlined, “Degree? Yes. Job? Maybe Not Yet.”

The article starts out by talking about the re-employment rate for new entrants to the workforce and shows us that it is far lower than for more experienced workers. This is shown with a large graph.

Next in the piece we do get the employment rate for all young people, not just recent grads, which has fallen in recent months back to levels reached in 2016, after previously reaching levels that were close to pre-pandemic peaks.

It is only towards the bottom of the piece that we get the unemployment rate for recent grads (4.3 percent). This is up slightly from the 3.9 percent low hit in 2022, but still low by most standards and very comparable to the rates we saw just before the pandemic.

As a practical matter, it is hard to imagine that someone could look at a 4.3 percent unemployment rate and say college grads are having a hard time finding jobs. Oddly, this is the second time in two weeks we saw this re-employment rate for recent grads highlighted as meaning that college grads are having trouble getting jobs.

The market for recent college grads continues to look pretty good, but the market for bad news on the economy is red hot.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

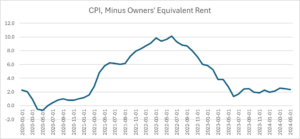

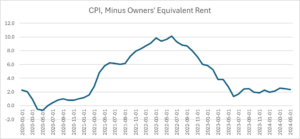

That’s a bit of an exaggeration, but the Consumer Price Index (CPI), excluding owners’ equivalent rent (OER) fell to 1.4 percent in June 2023 and has remained pretty close, but mostly above 2.0 percent ever since. We all know the Fed targets the Personal Consumption Expenditure Deflator, where the OER has a smaller weight, but it is still worth seeing how much this one category affects the CPI.

OER is not just a major expenditure category, it is also unusual in the sense that literally no one pays it. This is the rent that homeowners would be paying themselves if they had to rent the home they lived in. For this reason, it’s probably fair to say that no one considers themselves worse off because OER has risen. (They may consider themselves poorer because the cost of buying a home has increased, but that is a somewhat different question.)

Anyhow, here is the picture since the start of 2020.[1]

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics and Author’s Calculations.

As can be seen, just before the pandemic inflation minus OER was actually slightly above the Fed’s 2.0 percent target. With the pandemic shutdowns, it plunged and even briefly turned negative. It then accelerated sharply in early 2021 as supply chain issues sent inflation soaring. OER actually dampened inflation somewhat as it was peaking in the spring of 2022. It would have scraped into the double-digits in June 2022. It then fell sharply over the next year, bottoming out at 1.4 percent in June of 2023. Since then, it has bounced around some but remained reasonably close to 2.0 percent.

Apart from the issue that no one pays OER, there is a reason to be interested in the CPI excluding both the current OER measure as well as the measure of rent proper. We know that inflation in both measures will be headed sharply lower in the months ahead because the indexes that measure the rents on units that change hands are showing sharply lower rents.

The CPI rental indexes are being held up now by leases signed one or more years ago. When these leases are up for renewal, they will show much lower increases, and many may report rent declines. As these new leases get incorporated into the CPI, the inflation shown in its rental indexes will fall sharply, possibly near zero. Instead of being a factor pushing up the overall inflation rate, rent may be a factor pulling it down.

[1] To calculate the CPI without OER, I averaged the relative importance of January of each year and January of the following year and applied it as the weight assigned to year-over-year OER inflation in each month of that year. For 2024, I just used the January relative importance for the first five months of the year.

That’s a bit of an exaggeration, but the Consumer Price Index (CPI), excluding owners’ equivalent rent (OER) fell to 1.4 percent in June 2023 and has remained pretty close, but mostly above 2.0 percent ever since. We all know the Fed targets the Personal Consumption Expenditure Deflator, where the OER has a smaller weight, but it is still worth seeing how much this one category affects the CPI.

OER is not just a major expenditure category, it is also unusual in the sense that literally no one pays it. This is the rent that homeowners would be paying themselves if they had to rent the home they lived in. For this reason, it’s probably fair to say that no one considers themselves worse off because OER has risen. (They may consider themselves poorer because the cost of buying a home has increased, but that is a somewhat different question.)

Anyhow, here is the picture since the start of 2020.[1]

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics and Author’s Calculations.

As can be seen, just before the pandemic inflation minus OER was actually slightly above the Fed’s 2.0 percent target. With the pandemic shutdowns, it plunged and even briefly turned negative. It then accelerated sharply in early 2021 as supply chain issues sent inflation soaring. OER actually dampened inflation somewhat as it was peaking in the spring of 2022. It would have scraped into the double-digits in June 2022. It then fell sharply over the next year, bottoming out at 1.4 percent in June of 2023. Since then, it has bounced around some but remained reasonably close to 2.0 percent.

Apart from the issue that no one pays OER, there is a reason to be interested in the CPI excluding both the current OER measure as well as the measure of rent proper. We know that inflation in both measures will be headed sharply lower in the months ahead because the indexes that measure the rents on units that change hands are showing sharply lower rents.

The CPI rental indexes are being held up now by leases signed one or more years ago. When these leases are up for renewal, they will show much lower increases, and many may report rent declines. As these new leases get incorporated into the CPI, the inflation shown in its rental indexes will fall sharply, possibly near zero. Instead of being a factor pushing up the overall inflation rate, rent may be a factor pulling it down.

[1] To calculate the CPI without OER, I averaged the relative importance of January of each year and January of the following year and applied it as the weight assigned to year-over-year OER inflation in each month of that year. For 2024, I just used the January relative importance for the first five months of the year.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión