The Washington Post had a news quiz that included the results of a survey showing how much money people thought we had given to Ukraine. What is striking is not just that people were wrong, but rather they were insanely wrong. (Post readers thankfully did considerably better than the people responding to the poll.)

The first question asked people how much aid we gave to Ukraine measured as a share of GDP. The correct number is around 0.5 percent of GDP, or $140 billion. (I haven’t tried to add it up carefully, so I am taking the Post at its word here.) According to the Post, 46 percent of people answered that we had spent close to 10 percent of GDP, which would come to $2.8 trillion. The piece reported that 23 percent answered that we spent an amount that was more than 20 percent of GDP, or $5.6 trillion.

The second number asked how Ukraine spending compared to Social Security spending. Forty two percent said we spend about the same on Ukraine as on Social Security and 28 percent said 18 times more. We spend roughly $1.4 trillion a year on Social Security, which means that over the last two years we have spent close to 20 times as much on Social Security as on Ukraine.

No one can expect the average person to know with any precision how much money the government is spending on Ukraine or anything else. People have jobs. They don’t have time to go digging through budget documents to figure out where the government’s money is going. But we might expect that they would be somewhere in the ballpark, maybe off by a factor of two or three, but not a factor of 20 or 40.

If people believe that we are spending twenty times as much on Ukraine as is actually the case, what does it mean when they say they are opposed to aiding Ukraine? Are they opposed to giving Ukraine the amount of money that is actually on the table or are they opposing giving an amount that is twenty times as large, which absolutely no one is proposing?

Part of this story is that the politicians opposed to aiding Ukraine have reason to lie about the money being spent. To advance their case they would like people to believe that the money going to Ukraine is preventing the government from spending money on popular domestic items. For this reason, they are happy to talk about Ukraine aid as though it is twenty or even forty times larger than is actually the case.

However, part of the blame for this extreme ignorance can be laid at the doorstep of the media. They routinely refer to spending amounts in the billions or tens of billions of dollars, sums that are meaningless to almost everyone who sees them.

It would be a very simple matter to refer to these numbers as shares of the budget. For example, the $60 billion proposal current on the table is equal to approximately 0.9 percent of this year’s budget. If the media routinely reported budget numbers in a way that provided some context, it is less likely that we would find that the vast majority of the public overstates spending on Ukraine or other items by an order of magnitude.

For what it’s worth, people in the media do recognize this problem. However, for some reason they refuse to do anything to address it. I will also add that there are entirely legitimate reasons that people may oppose aid to Ukraine, however being 10 percent of GDP is not one of them.

The Washington Post had a news quiz that included the results of a survey showing how much money people thought we had given to Ukraine. What is striking is not just that people were wrong, but rather they were insanely wrong. (Post readers thankfully did considerably better than the people responding to the poll.)

The first question asked people how much aid we gave to Ukraine measured as a share of GDP. The correct number is around 0.5 percent of GDP, or $140 billion. (I haven’t tried to add it up carefully, so I am taking the Post at its word here.) According to the Post, 46 percent of people answered that we had spent close to 10 percent of GDP, which would come to $2.8 trillion. The piece reported that 23 percent answered that we spent an amount that was more than 20 percent of GDP, or $5.6 trillion.

The second number asked how Ukraine spending compared to Social Security spending. Forty two percent said we spend about the same on Ukraine as on Social Security and 28 percent said 18 times more. We spend roughly $1.4 trillion a year on Social Security, which means that over the last two years we have spent close to 20 times as much on Social Security as on Ukraine.

No one can expect the average person to know with any precision how much money the government is spending on Ukraine or anything else. People have jobs. They don’t have time to go digging through budget documents to figure out where the government’s money is going. But we might expect that they would be somewhere in the ballpark, maybe off by a factor of two or three, but not a factor of 20 or 40.

If people believe that we are spending twenty times as much on Ukraine as is actually the case, what does it mean when they say they are opposed to aiding Ukraine? Are they opposed to giving Ukraine the amount of money that is actually on the table or are they opposing giving an amount that is twenty times as large, which absolutely no one is proposing?

Part of this story is that the politicians opposed to aiding Ukraine have reason to lie about the money being spent. To advance their case they would like people to believe that the money going to Ukraine is preventing the government from spending money on popular domestic items. For this reason, they are happy to talk about Ukraine aid as though it is twenty or even forty times larger than is actually the case.

However, part of the blame for this extreme ignorance can be laid at the doorstep of the media. They routinely refer to spending amounts in the billions or tens of billions of dollars, sums that are meaningless to almost everyone who sees them.

It would be a very simple matter to refer to these numbers as shares of the budget. For example, the $60 billion proposal current on the table is equal to approximately 0.9 percent of this year’s budget. If the media routinely reported budget numbers in a way that provided some context, it is less likely that we would find that the vast majority of the public overstates spending on Ukraine or other items by an order of magnitude.

For what it’s worth, people in the media do recognize this problem. However, for some reason they refuse to do anything to address it. I will also add that there are entirely legitimate reasons that people may oppose aid to Ukraine, however being 10 percent of GDP is not one of them.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The New York Times had a piece on the tax code changes that will take effect next year unless Congress acts to extend current provisions. One of the items on this list is an increase in the amount of wealth exempted from the estate tax.

The piece lists the amount currently exempted as $13.6 million, with the possibility it will revert back to its pre-Trump level of $5 million (adjusted somewhat higher for inflation) if the Trump provision is not extended. It is important to point out that this is the exemption for a single individual. A couple would be able to pass on $27.2 million to their heirs without paying any tax whatsoever.

This tax applies to less than 2,000 estates a year, less than 0.1 percent of all estates. Even with the $5 million cutoff only around 5,000 estates paid the tax.

It is also important to recognize that the tax is marginal — it only applies to wealth above the cutoff. This means for example, that a couple with an estate of $27.5 million would only pay the 40 percent tax on the $300,000 above the cutoff. In this case the heirs would face a tax liability of $120,000, less than 0.5 percent of the estate.

The New York Times had a piece on the tax code changes that will take effect next year unless Congress acts to extend current provisions. One of the items on this list is an increase in the amount of wealth exempted from the estate tax.

The piece lists the amount currently exempted as $13.6 million, with the possibility it will revert back to its pre-Trump level of $5 million (adjusted somewhat higher for inflation) if the Trump provision is not extended. It is important to point out that this is the exemption for a single individual. A couple would be able to pass on $27.2 million to their heirs without paying any tax whatsoever.

This tax applies to less than 2,000 estates a year, less than 0.1 percent of all estates. Even with the $5 million cutoff only around 5,000 estates paid the tax.

It is also important to recognize that the tax is marginal — it only applies to wealth above the cutoff. This means for example, that a couple with an estate of $27.5 million would only pay the 40 percent tax on the $300,000 above the cutoff. In this case the heirs would face a tax liability of $120,000, less than 0.5 percent of the estate.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

That is effectively what the state of Texas and Florida are arguing before the Supreme Court this week. This argument goes under the guise of whether states can prohibit social media companies from banning material based on politics. However, since much of Republican politics these days involves promulgating lies, like the “Biden family” Ukraine bribery story, the Texas and Florida law could arguably mean that the state could require Facebook and other social media sites to spread lies.

There is a lot of tortured reasoning around the major social media platforms these days. The Texas and Florida laws are justified by saying these platforms are essentially common carriers, like a phone company.

That one seems pretty hard to justify. In principle at least, a phone company would have no control over, or even knowledge of, the content of phone calls. This would make it absurd for a state government to try to dictate what sort of calls could or could not be made over a telephone network.

Social media platforms do have knowledge of the material that gets posted on their sites. And in fact they make conscious decisions, or at least have algorithms that decide for them, whether to leave up a post, boost it so that it is seen by a wide audience, or remove it altogether.

The social media companies arguing against the Florida and Texas laws say that they have a First Amendment right to decide what material they want to promote and what material they want to exclude, just like a print or broadcast outlet. However, there is an important difference between the factors that print and broadcast outlets must consider in transmitting and promoting content and what social media sites need to consider.

Modifying Section 230

Print and broadcast outlets can be sued for defamation for transmitting material that is false and harmful to individuals or organizations. Social media sites do not have this concern because they are protected by Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act.

This means that not only are social media companies not liable for spreading defamatory material, they actually can profit from it. This is not only the case for big political lies. If some racist decides to buy ads on Facebook or Twitter falsely saying that they got food poisoning at a Black-owned restaurant, Mark Zuckerberg or Elon Musk get to pocket the cash.

The restaurant owner could sue the person who took out the ad, if they can find them (ads can be posted under phony names), but Facebook and Twitter would just hold up their Section 230 immunity and walk away with the cash. The same story applies to posts on these sites. These can also generate profits for Mr. Zuckerberg or Mr. Musk, since defamatory material may increase views and make advertising more valuable.

The ostensible rationale for Section 230 was that we want social media companies to be able to moderate their sites for pornographic material or posts that seek to incite violence, without fear of being sued. There is also the argument that a major social media platform can’t possibly monitor all of the hundreds of millions, or even billions, of posts that go up every day.

But removing protections against defamation suits does not in any way interfere with the first goal. Facebook or Twitter should not have to worry about being sued for defamation because they remove child pornography.

As far as the second point, while it is true that these sites cannot monitor every post as it goes up, they could respond to takedown notices that come from individuals or organizations claiming they have been defamed. There is an obvious model here. The Digital Millennium Copyright Act requires that companies remove material that infringes on copyright, after they have been notified by the copyright holder or their agent. If they remove the material in a timely manner, they are protected against a lawsuit. Alternatively, they may determine that the material is not infringing and leave it up.

We can have a similar process with allegedly defamatory material, where the person or organization claiming defamation has to spell out exactly how the material is defamatory. The site then has the option to either take the material down, or leave it posted and risk a defamation suit.

This would effectively be treating social media sites like print or broadcast media. These outlets must take responsibility for the material they transmit to their audience, even if it comes from third parties. (Fox paid $787 million to Dominion as a result of a lawsuit largely over statements by guests on Fox shows.) There is not an obvious reason why CNN can be sued for carrying an ad falsely claiming that a prominent person is a pedophile, but Twitter and Facebook get to pocket the cash with impunity.

We can also structure this sort of change in Section 230 in a way that favors smaller sites. We can leave the current rules for Section 230 in place for sites that don’t sell ads or personal information. Sites that support themselves by subscriptions or donations could continue to operate as they do now.

This would help to counteract the network effects that tend to push people towards the biggest sites. After all, if Facebook and Twitter were each just one of a hundred social media sites that people used to post their thoughts, no one would especially care what posts they choose to amplify or remove. If users didn’t like their editorial choices, they would just opt for a different one, just as they do now with newspapers or television stations.

It is only because these social media sites have such a huge share of the market that their decisions take on so much importance. If we can restructure Section 230 in a way that downsizes these giants, it will go far towards ending the problem.

Modifying Section 230 won’t fix all the problems with social media, but it does remove an obvious asymmetry in the law. As it now stands, print and broadcast outlets can get sued for carrying defamatory material, but social media sites cannot. This situation does not make sense and should be changed.

That is effectively what the state of Texas and Florida are arguing before the Supreme Court this week. This argument goes under the guise of whether states can prohibit social media companies from banning material based on politics. However, since much of Republican politics these days involves promulgating lies, like the “Biden family” Ukraine bribery story, the Texas and Florida law could arguably mean that the state could require Facebook and other social media sites to spread lies.

There is a lot of tortured reasoning around the major social media platforms these days. The Texas and Florida laws are justified by saying these platforms are essentially common carriers, like a phone company.

That one seems pretty hard to justify. In principle at least, a phone company would have no control over, or even knowledge of, the content of phone calls. This would make it absurd for a state government to try to dictate what sort of calls could or could not be made over a telephone network.

Social media platforms do have knowledge of the material that gets posted on their sites. And in fact they make conscious decisions, or at least have algorithms that decide for them, whether to leave up a post, boost it so that it is seen by a wide audience, or remove it altogether.

The social media companies arguing against the Florida and Texas laws say that they have a First Amendment right to decide what material they want to promote and what material they want to exclude, just like a print or broadcast outlet. However, there is an important difference between the factors that print and broadcast outlets must consider in transmitting and promoting content and what social media sites need to consider.

Modifying Section 230

Print and broadcast outlets can be sued for defamation for transmitting material that is false and harmful to individuals or organizations. Social media sites do not have this concern because they are protected by Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act.

This means that not only are social media companies not liable for spreading defamatory material, they actually can profit from it. This is not only the case for big political lies. If some racist decides to buy ads on Facebook or Twitter falsely saying that they got food poisoning at a Black-owned restaurant, Mark Zuckerberg or Elon Musk get to pocket the cash.

The restaurant owner could sue the person who took out the ad, if they can find them (ads can be posted under phony names), but Facebook and Twitter would just hold up their Section 230 immunity and walk away with the cash. The same story applies to posts on these sites. These can also generate profits for Mr. Zuckerberg or Mr. Musk, since defamatory material may increase views and make advertising more valuable.

The ostensible rationale for Section 230 was that we want social media companies to be able to moderate their sites for pornographic material or posts that seek to incite violence, without fear of being sued. There is also the argument that a major social media platform can’t possibly monitor all of the hundreds of millions, or even billions, of posts that go up every day.

But removing protections against defamation suits does not in any way interfere with the first goal. Facebook or Twitter should not have to worry about being sued for defamation because they remove child pornography.

As far as the second point, while it is true that these sites cannot monitor every post as it goes up, they could respond to takedown notices that come from individuals or organizations claiming they have been defamed. There is an obvious model here. The Digital Millennium Copyright Act requires that companies remove material that infringes on copyright, after they have been notified by the copyright holder or their agent. If they remove the material in a timely manner, they are protected against a lawsuit. Alternatively, they may determine that the material is not infringing and leave it up.

We can have a similar process with allegedly defamatory material, where the person or organization claiming defamation has to spell out exactly how the material is defamatory. The site then has the option to either take the material down, or leave it posted and risk a defamation suit.

This would effectively be treating social media sites like print or broadcast media. These outlets must take responsibility for the material they transmit to their audience, even if it comes from third parties. (Fox paid $787 million to Dominion as a result of a lawsuit largely over statements by guests on Fox shows.) There is not an obvious reason why CNN can be sued for carrying an ad falsely claiming that a prominent person is a pedophile, but Twitter and Facebook get to pocket the cash with impunity.

We can also structure this sort of change in Section 230 in a way that favors smaller sites. We can leave the current rules for Section 230 in place for sites that don’t sell ads or personal information. Sites that support themselves by subscriptions or donations could continue to operate as they do now.

This would help to counteract the network effects that tend to push people towards the biggest sites. After all, if Facebook and Twitter were each just one of a hundred social media sites that people used to post their thoughts, no one would especially care what posts they choose to amplify or remove. If users didn’t like their editorial choices, they would just opt for a different one, just as they do now with newspapers or television stations.

It is only because these social media sites have such a huge share of the market that their decisions take on so much importance. If we can restructure Section 230 in a way that downsizes these giants, it will go far towards ending the problem.

Modifying Section 230 won’t fix all the problems with social media, but it does remove an obvious asymmetry in the law. As it now stands, print and broadcast outlets can get sued for carrying defamatory material, but social media sites cannot. This situation does not make sense and should be changed.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Most people don’t keep up on the details of government policy. This is understandable because they have lives to live, and can’t spend all their time following the structure of various government programs. However, it is unfortunate when their lack of knowledge prevents them from using a government program that could benefit them greatly.

This is true of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) which created health care exchanges that allow tens of millions of people to get insurance with large subsidies. Many people who could benefit from these subsidies, which in many cases cover the full cost of a policy, don’t take advantage of the exchanges because they don’t know about the subsidies.

Apparently, this ignorance applies to New York Times columnists and editors. A New York Times column trashing the Biden economy (a regular feature of the paper) told readers about benefit cliffs that many moderate-income families face. The story is that many people lose Medicaid, food stamps, or other benefits when their income rises above certain thresholds.

While this is a real problem, the specific example given in the piece is not.

“A helpful starting point would be to address benefit cliffs — income eligibility cutoffs built into certain benefits programs. As households earn more money, they can make themselves suddenly ineligible for benefits that would let them build up enough wealth to no longer need any government support. In Kansas, for example, a family of four remains eligible for Medicaid as long as it earns under $39,900. A single dollar in additional income results in the loss of health care coverage — and an alternative will certainly not cost only a buck.”

There are two problems with this story. First, a family of four would almost certainly be eligible for the CHIP program, which in Kansas provides health insurance for children for families that earn up to 250 percent of the federal poverty level, which is $78,000 for a family of four.

The other problem is that this family would be eligible for a full subsidy for a silver plan (middle quality) in the exchanges created by the ACA as long as their income was under $45,000. Even with an income of $60,000 a year, they would only be paying $1,200 a year for their insurance.

It is unfortunate that people who could benefit from the Obamacare exchanges often don’t. If our country’s leading newspaper could be bothered to give correct information, maybe there would be fewer people in this category.

Most people don’t keep up on the details of government policy. This is understandable because they have lives to live, and can’t spend all their time following the structure of various government programs. However, it is unfortunate when their lack of knowledge prevents them from using a government program that could benefit them greatly.

This is true of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) which created health care exchanges that allow tens of millions of people to get insurance with large subsidies. Many people who could benefit from these subsidies, which in many cases cover the full cost of a policy, don’t take advantage of the exchanges because they don’t know about the subsidies.

Apparently, this ignorance applies to New York Times columnists and editors. A New York Times column trashing the Biden economy (a regular feature of the paper) told readers about benefit cliffs that many moderate-income families face. The story is that many people lose Medicaid, food stamps, or other benefits when their income rises above certain thresholds.

While this is a real problem, the specific example given in the piece is not.

“A helpful starting point would be to address benefit cliffs — income eligibility cutoffs built into certain benefits programs. As households earn more money, they can make themselves suddenly ineligible for benefits that would let them build up enough wealth to no longer need any government support. In Kansas, for example, a family of four remains eligible for Medicaid as long as it earns under $39,900. A single dollar in additional income results in the loss of health care coverage — and an alternative will certainly not cost only a buck.”

There are two problems with this story. First, a family of four would almost certainly be eligible for the CHIP program, which in Kansas provides health insurance for children for families that earn up to 250 percent of the federal poverty level, which is $78,000 for a family of four.

The other problem is that this family would be eligible for a full subsidy for a silver plan (middle quality) in the exchanges created by the ACA as long as their income was under $45,000. Even with an income of $60,000 a year, they would only be paying $1,200 a year for their insurance.

It is unfortunate that people who could benefit from the Obamacare exchanges often don’t. If our country’s leading newspaper could be bothered to give correct information, maybe there would be fewer people in this category.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

George Will used his Washington Post column to go on a diatribe against proposals for subsidizing local news outlets. After noting the plunge in the number of local newspapers, and an even sharper drop in the employment of journalists (down two-thirds since 2005), Will attacks the ideas for public support of journalism developed by Illinois Task Force on Local Journalism.

Will lists various forms of proposed subsidies and then tells readers:

“What could go wrong? Everything.

“Soon, government would mandate hiring and coverage quotas for “underrepresented” groups, would enforce government’s idea of editorial “balance,” would censor what government considers “misinformation” about public health, diversity, equity and inclusion, and would dictate all things pertinent to government’s ever-lengthening agenda. The task force’s recommendations — journalism throwing itself into government’s muscular arms — are a recipe for making local news sources as admired and trusted as government is.”

If Will is really this adverse to government subsidies, then it is bizarre that he is not also ranting against government subsidies for cultural institutions, charitable organizations, and churches through the charitable contribution tax deduction. This deduction, which is almost exclusively used by high-income people, allows people to reduce their taxable income by the amount of their contribution.

For a rich person who faces roughly a 40 percent marginal tax rate, this means that the government pays for 40 percent of their contribution. That means if a rich person chooses to give $1 billion to a think tank, a church, or some other qualifying organization, the taxpayers pick up $400 million of the tab, effectively meaning this $1 billion contribution only cost the rich person $600 million.

For some reason, we haven’t seen a George Will rant in the Washington Post against this very large government subsidy. Is he unconcerned that the government will mandate hiring quotas, have diversity, equity, and inclusion requirements and other things he views as evil as conditions for being the tax deduction?

If this is not a concern with the charitable contribution tax deduction, why would it be a concern with other forms of government subsidies for news organizations? In fact, many news outlets, such ProPublica, are now organized as charitable organizations and benefit directly from this tax deduction.

In fact, some forms of subsidies are explicitly modelled on the charitable contribution tax deduction. Proposals in Washington, DC and Seattle, Washington would effectively give each resident a tax credit (e.g. $100) to support the local news outlet of their choice. This is comparable to the tax deduction, except that it would give the same amount to everyone, even people who are not paying taxes.

If Will is comfortable that we can handle the charitable contribution tax deduction without serious abuses, it is difficult to see why he is so confident that a tax credit would be subject to massive abuse. (It’s also worth mentioning that government-granted copyright monopolies are an explicit subsidy, as readers of the constitution know well.)

Will has an important point in his column. We do want to encourage a press that is independent of government interference. This is a fair warning about how subsidies for local journalism should be structured. However, the track record shows that this turf can be, and is being, navigated well. That could change in the future (Donald Trump has explicitly indicated that he doesn’t give a damn about freedom of the press), but the risks here seem small relative to the potential benefits.

George Will used his Washington Post column to go on a diatribe against proposals for subsidizing local news outlets. After noting the plunge in the number of local newspapers, and an even sharper drop in the employment of journalists (down two-thirds since 2005), Will attacks the ideas for public support of journalism developed by Illinois Task Force on Local Journalism.

Will lists various forms of proposed subsidies and then tells readers:

“What could go wrong? Everything.

“Soon, government would mandate hiring and coverage quotas for “underrepresented” groups, would enforce government’s idea of editorial “balance,” would censor what government considers “misinformation” about public health, diversity, equity and inclusion, and would dictate all things pertinent to government’s ever-lengthening agenda. The task force’s recommendations — journalism throwing itself into government’s muscular arms — are a recipe for making local news sources as admired and trusted as government is.”

If Will is really this adverse to government subsidies, then it is bizarre that he is not also ranting against government subsidies for cultural institutions, charitable organizations, and churches through the charitable contribution tax deduction. This deduction, which is almost exclusively used by high-income people, allows people to reduce their taxable income by the amount of their contribution.

For a rich person who faces roughly a 40 percent marginal tax rate, this means that the government pays for 40 percent of their contribution. That means if a rich person chooses to give $1 billion to a think tank, a church, or some other qualifying organization, the taxpayers pick up $400 million of the tab, effectively meaning this $1 billion contribution only cost the rich person $600 million.

For some reason, we haven’t seen a George Will rant in the Washington Post against this very large government subsidy. Is he unconcerned that the government will mandate hiring quotas, have diversity, equity, and inclusion requirements and other things he views as evil as conditions for being the tax deduction?

If this is not a concern with the charitable contribution tax deduction, why would it be a concern with other forms of government subsidies for news organizations? In fact, many news outlets, such ProPublica, are now organized as charitable organizations and benefit directly from this tax deduction.

In fact, some forms of subsidies are explicitly modelled on the charitable contribution tax deduction. Proposals in Washington, DC and Seattle, Washington would effectively give each resident a tax credit (e.g. $100) to support the local news outlet of their choice. This is comparable to the tax deduction, except that it would give the same amount to everyone, even people who are not paying taxes.

If Will is comfortable that we can handle the charitable contribution tax deduction without serious abuses, it is difficult to see why he is so confident that a tax credit would be subject to massive abuse. (It’s also worth mentioning that government-granted copyright monopolies are an explicit subsidy, as readers of the constitution know well.)

Will has an important point in his column. We do want to encourage a press that is independent of government interference. This is a fair warning about how subsidies for local journalism should be structured. However, the track record shows that this turf can be, and is being, navigated well. That could change in the future (Donald Trump has explicitly indicated that he doesn’t give a damn about freedom of the press), but the risks here seem small relative to the potential benefits.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The media are pushing the economy is terrible story pretty much 24-7. They refuse to let the strong labor market and rapid real wage growth get in their way. They seem to want everyone to think things are really bad, in spite of a 24-month stretch of below 4.0 percent unemployment and a sharp reduction in wage inequality since the pandemic.

The latest item in this effort was a New York Times piece about how the economy is rigged. It told readers about the bad times exemplified by an explosion of credit card debt. While credit card debt is rising rapidly, it is not quite the horror story the piece would have you believe.

Credit card debt virtually stopped growing in 2020-22. There were two reasons. First, the pandemic checks meant that many households were flush with cash and had no reason to borrow on their credit card.

The second reason is that we had an unprecedented boom in mortgage refinancing, with more than 14 million people taking advantage of the low rates available during these years. Many of these households borrowed extra cash when they refinanced, meaning they had no reason to borrow on their credit cards.

Those who didn’t do cash-out refinancing saved an average of $2,500 a year on interest. Somehow this fact has gone almost unnoticed among those commenting on the economy.

With the cash people saved in the pandemic getting run down, and the refinancing window closed due to the jump in mortgage rates, people are again turning to credit cards. But we are just back to roughly our pre-pandemic trend, as shown below. (By the way, anyone who says that credit card debt is at a record high is just trying to tell you that they know nothing about the economy. Just like GDP and income, credit card debt is almost always hitting a record high.)

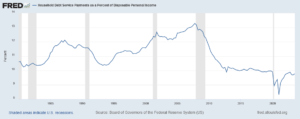

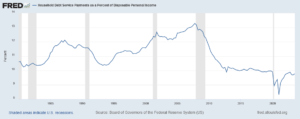

If we are worried about the burden of interest payments on family budgets, then we can look at the ratio of debt service to income, which includes the burden of all loans, not just credit cards. Here’s the picture.

As can be seen, instead of the horrible burden story, the ratio is near a four-decade low, with the pandemic years being the only time when it was lower.

To be clear, tens of millions of people are struggling to pay their rent and put food on the table, but that was also true when Donald Trump was in the White House. In those years, the NYT and other major media outlets did not feel the need to constantly run pieces saying how awful the economy was.

I will also add that the economy is in fact rigged, but not in ways that the New York Times will let people talk about in its pages. The government grants patent and copyright monopolies that make folks like Bill Gates incredibly rich and drugs incredibly expensive. Our system of corporate governance is a cesspool, with top executives making tens of millions annually at the expense of their companies and hugely skewing wage patterns throughout the economy. The bloated financial system siphons hundreds of billions annually from the rest of us and hands it to hedge fund and private equity tycoons.

We could structure the economy differently so that less of the benefits of growth go to those at the top. But the major media outlets do not want to have that sort of discussion. They just want to tell people that things are bad under Biden.

The media are pushing the economy is terrible story pretty much 24-7. They refuse to let the strong labor market and rapid real wage growth get in their way. They seem to want everyone to think things are really bad, in spite of a 24-month stretch of below 4.0 percent unemployment and a sharp reduction in wage inequality since the pandemic.

The latest item in this effort was a New York Times piece about how the economy is rigged. It told readers about the bad times exemplified by an explosion of credit card debt. While credit card debt is rising rapidly, it is not quite the horror story the piece would have you believe.

Credit card debt virtually stopped growing in 2020-22. There were two reasons. First, the pandemic checks meant that many households were flush with cash and had no reason to borrow on their credit card.

The second reason is that we had an unprecedented boom in mortgage refinancing, with more than 14 million people taking advantage of the low rates available during these years. Many of these households borrowed extra cash when they refinanced, meaning they had no reason to borrow on their credit cards.

Those who didn’t do cash-out refinancing saved an average of $2,500 a year on interest. Somehow this fact has gone almost unnoticed among those commenting on the economy.

With the cash people saved in the pandemic getting run down, and the refinancing window closed due to the jump in mortgage rates, people are again turning to credit cards. But we are just back to roughly our pre-pandemic trend, as shown below. (By the way, anyone who says that credit card debt is at a record high is just trying to tell you that they know nothing about the economy. Just like GDP and income, credit card debt is almost always hitting a record high.)

If we are worried about the burden of interest payments on family budgets, then we can look at the ratio of debt service to income, which includes the burden of all loans, not just credit cards. Here’s the picture.

As can be seen, instead of the horrible burden story, the ratio is near a four-decade low, with the pandemic years being the only time when it was lower.

To be clear, tens of millions of people are struggling to pay their rent and put food on the table, but that was also true when Donald Trump was in the White House. In those years, the NYT and other major media outlets did not feel the need to constantly run pieces saying how awful the economy was.

I will also add that the economy is in fact rigged, but not in ways that the New York Times will let people talk about in its pages. The government grants patent and copyright monopolies that make folks like Bill Gates incredibly rich and drugs incredibly expensive. Our system of corporate governance is a cesspool, with top executives making tens of millions annually at the expense of their companies and hugely skewing wage patterns throughout the economy. The bloated financial system siphons hundreds of billions annually from the rest of us and hands it to hedge fund and private equity tycoons.

We could structure the economy differently so that less of the benefits of growth go to those at the top. But the major media outlets do not want to have that sort of discussion. They just want to tell people that things are bad under Biden.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

There have been numerous stories in recent months about how housing is unaffordable for millions of people. This is certainly true. An inadequate supply of affordable housing is one of the major problems facing the country, and especially young people and minorities.

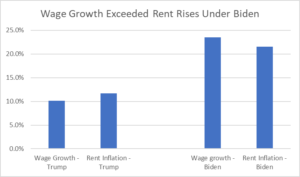

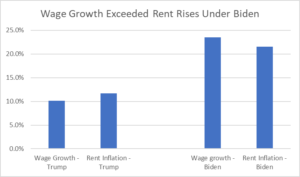

However, data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics indicate that rent on average has become more affordable for people now than it had been when Donald Trump was in the White House. Wage growth has actually exceeded the rate of rental inflation since President Biden took office.

Here’s the picture for the two presidents.

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics and author’s calculations.

The chart shows wage growth for production and non-supervisory workers. This group comprises roughly 80 percent of employees. It excludes managers and highly paid professionals, so it is not affected by rapid wage growth at the top end of the wage distribution. It closely tracks the median wage.

For Trump, I took the period from January of 2017, when he took office, until February of 2020, the last month before the pandemic began skewing the data. For Biden, I took the period from February 2020 to January 2024. This effectively compares current wages to their pre-pandemic level.

As can be seen, nominal wages grew by 10.1 percent under Trump. However, average rents increased 11.7 percent, meaning workers’ wages fell behind rental inflation under Trump.

Rental inflation jumped sharply during the pandemic, as people working from home needed more room. They also had the money saved from commuting-related expenses to pay for it. Rents rose by 21.6 percent under Biden. However, the average wage increased by 23.5 percent, almost 2.0 full percentage points more than rent.

Averages don’t tell us everything, there are many areas where rents rose more rapidly than the national average. And not all workers saw wage increases that kept pace with the average, although we do know that wage increases were more rapid for those at the bottom end of the distribution. This means that rent should be more affordable today for the typical worker than was the case when Donald Trump was in the White House.

This doesn’t mean that housing is not a serious problem. Tens of millions of people are inadequately housed, and hundreds of thousands are homeless altogether, living on streets and in shelters. In the short term measures like rent control, converting vacant office space to residential units, and restrictions on vacation rentals can help. In the longer term we need to relax zoning restrictions and take other measures to build more housing.

But the bottom line here is clear. It is hard to tell a story based on the data where affordable housing is a greater problem today than before President Biden took office. For some reason the media have chosen to highlight the problem today to a much greater extent than before the pandemic.

There have been numerous stories in recent months about how housing is unaffordable for millions of people. This is certainly true. An inadequate supply of affordable housing is one of the major problems facing the country, and especially young people and minorities.

However, data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics indicate that rent on average has become more affordable for people now than it had been when Donald Trump was in the White House. Wage growth has actually exceeded the rate of rental inflation since President Biden took office.

Here’s the picture for the two presidents.

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics and author’s calculations.

The chart shows wage growth for production and non-supervisory workers. This group comprises roughly 80 percent of employees. It excludes managers and highly paid professionals, so it is not affected by rapid wage growth at the top end of the wage distribution. It closely tracks the median wage.

For Trump, I took the period from January of 2017, when he took office, until February of 2020, the last month before the pandemic began skewing the data. For Biden, I took the period from February 2020 to January 2024. This effectively compares current wages to their pre-pandemic level.

As can be seen, nominal wages grew by 10.1 percent under Trump. However, average rents increased 11.7 percent, meaning workers’ wages fell behind rental inflation under Trump.

Rental inflation jumped sharply during the pandemic, as people working from home needed more room. They also had the money saved from commuting-related expenses to pay for it. Rents rose by 21.6 percent under Biden. However, the average wage increased by 23.5 percent, almost 2.0 full percentage points more than rent.

Averages don’t tell us everything, there are many areas where rents rose more rapidly than the national average. And not all workers saw wage increases that kept pace with the average, although we do know that wage increases were more rapid for those at the bottom end of the distribution. This means that rent should be more affordable today for the typical worker than was the case when Donald Trump was in the White House.

This doesn’t mean that housing is not a serious problem. Tens of millions of people are inadequately housed, and hundreds of thousands are homeless altogether, living on streets and in shelters. In the short term measures like rent control, converting vacant office space to residential units, and restrictions on vacation rentals can help. In the longer term we need to relax zoning restrictions and take other measures to build more housing.

But the bottom line here is clear. It is hard to tell a story based on the data where affordable housing is a greater problem today than before President Biden took office. For some reason the media have chosen to highlight the problem today to a much greater extent than before the pandemic.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

When it comes to economic issues, you can reliably count on the NYT opinion pages (except Paul Krugman) to be behind the times. In keeping with its reputation, the NYT had a column by Adelle Waldman about workers not being able to control their hours of work, and often getting fewer hours than they need to support themselves and their families.

To be clear, this is a very real problem. It matters if workers can’t count on a regular schedule and it certainly is a big deal if a worker who needs to put in 40 hours a week can only get 30 hours, or even less.

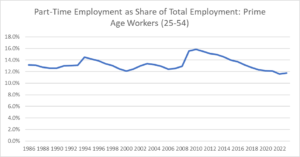

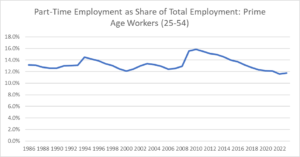

The problem with Waldman’s piece is that this issue of not controlling hours is almost certainly less of a problem in the current strong labor market than it has been in the past. The graph below shows the percentage of prime-age (25 to 54) workers who work part-time (less than 35 hours a week) as a share of total employment.

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics and author’s calculations.

There are a few things to note about this graph. First, I’m showing the shares for prime-age workers because many younger and older workers choose to work part-time. The second point is that the share moves counter-cyclically, it rises when the economy falls into recession, as it did in the early 1990 and the Great Recession and falls when the labor market is strong. This brings up the third point, that the part-time share is now near a record low.

In other words, the news about part-time employment is that the story today is relatively good, exactly the opposite of the thrust of this piece. This is likely one reason why workplace satisfaction is at a record high.

This is not to say that control over work hours is not an important issue. Millions of workers still can’t work as many hours as they need to support their families. Also, workers are often forced to work overtime, at risk of losing their jobs, or irregular hours that conflict with family obligations.

However, what is most bizarre about the piece is the ignorance it displays about battles over these issues:

“One of the most surprising aspects of this movement toward part-time work is how few white-collar people — including economists and policy analysts — have seemed to notice or appreciate it. So entrenched is the assumption that full-time work is on offer for most people who want it that even some Bureau of Labor Statistics data calculate annual earnings in various sectors by taking the hourly wage reported by participating employers and multiplying it by 2,080, the number of hours you’d work if you worked 40 hours a week, 52 weeks a year. Never mind that in the real world few workers in certain sectors are given the option of working full-time.”

The reason economists tend to focus on hourly wages is that many people opt to work part-time employment. (Roughly 80 percent of part-time employment is voluntary.) There is nothing wrong with people opting to work less than a full-time job if they want to have time to deal with family responsibilities, go to school, or simply pursue other activities. We usually want to distinguish between people seeing a fall in annual pay because they are paid less, as opposed to working fewer hours.

As far as economists ignoring involuntary part-time, as someone who has been writing about monthly employment reports for more than three decades, I always look at the number of people who report working part-time involuntarily. The same is true for most of the other people writing on these reports. It is hard to imagine a claim further from the truth.

And the issue of not controlling hours has been well-tread ground for decades. The same is the case with irregular and bad hours. This has long been a topic for labor activism, most notably efforts to impose restrictions of “clopening,” requiring workers to come in early to open a restaurant after they stayed late to close it the night before.

In short, control over work hours is in fact a very important issue. Unfortunately, Adelle Waldman’s piece has little to contribute to the debate.

When it comes to economic issues, you can reliably count on the NYT opinion pages (except Paul Krugman) to be behind the times. In keeping with its reputation, the NYT had a column by Adelle Waldman about workers not being able to control their hours of work, and often getting fewer hours than they need to support themselves and their families.

To be clear, this is a very real problem. It matters if workers can’t count on a regular schedule and it certainly is a big deal if a worker who needs to put in 40 hours a week can only get 30 hours, or even less.

The problem with Waldman’s piece is that this issue of not controlling hours is almost certainly less of a problem in the current strong labor market than it has been in the past. The graph below shows the percentage of prime-age (25 to 54) workers who work part-time (less than 35 hours a week) as a share of total employment.

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics and author’s calculations.

There are a few things to note about this graph. First, I’m showing the shares for prime-age workers because many younger and older workers choose to work part-time. The second point is that the share moves counter-cyclically, it rises when the economy falls into recession, as it did in the early 1990 and the Great Recession and falls when the labor market is strong. This brings up the third point, that the part-time share is now near a record low.

In other words, the news about part-time employment is that the story today is relatively good, exactly the opposite of the thrust of this piece. This is likely one reason why workplace satisfaction is at a record high.

This is not to say that control over work hours is not an important issue. Millions of workers still can’t work as many hours as they need to support their families. Also, workers are often forced to work overtime, at risk of losing their jobs, or irregular hours that conflict with family obligations.

However, what is most bizarre about the piece is the ignorance it displays about battles over these issues:

“One of the most surprising aspects of this movement toward part-time work is how few white-collar people — including economists and policy analysts — have seemed to notice or appreciate it. So entrenched is the assumption that full-time work is on offer for most people who want it that even some Bureau of Labor Statistics data calculate annual earnings in various sectors by taking the hourly wage reported by participating employers and multiplying it by 2,080, the number of hours you’d work if you worked 40 hours a week, 52 weeks a year. Never mind that in the real world few workers in certain sectors are given the option of working full-time.”

The reason economists tend to focus on hourly wages is that many people opt to work part-time employment. (Roughly 80 percent of part-time employment is voluntary.) There is nothing wrong with people opting to work less than a full-time job if they want to have time to deal with family responsibilities, go to school, or simply pursue other activities. We usually want to distinguish between people seeing a fall in annual pay because they are paid less, as opposed to working fewer hours.

As far as economists ignoring involuntary part-time, as someone who has been writing about monthly employment reports for more than three decades, I always look at the number of people who report working part-time involuntarily. The same is true for most of the other people writing on these reports. It is hard to imagine a claim further from the truth.

And the issue of not controlling hours has been well-tread ground for decades. The same is the case with irregular and bad hours. This has long been a topic for labor activism, most notably efforts to impose restrictions of “clopening,” requiring workers to come in early to open a restaurant after they stayed late to close it the night before.

In short, control over work hours is in fact a very important issue. Unfortunately, Adelle Waldman’s piece has little to contribute to the debate.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Yes, I am serious. Today’s “Dealbook Newsletter,” is headlined “Rethinking the Prospects of a Soft Landing.” The piece makes the case that the higher-than-expected January CPI, coupled with other data points, raises questions whether inflation is under control.

In making this case one section tells readers:

“Worry extends beyond the markets. The prospect of higher inflation is weighing on consumers and small-business owners.

“Meanwhile, Krispy Kreme, Coca-Cola and Heineken each warned this week that stubborn inflation could hurt their earnings.”

Just to say the obvious (I guess not obvious to Dealbook writers and editors), if these big consumer product companies are worried that they are going to be hurt by inflation, it means that they think they lack the pricing power to raise their prices further. As many have noted, part of the pandemic inflation story has been large companies taking advantage of their market power to jack up profit margins.

The story here, insofar as it is accurate, is that the economy has changed enough that big firms no longer have the pricing power they did one or two years ago. That is good news in the battle against inflation, not the bad news we are being told here.

Yes, I am serious. Today’s “Dealbook Newsletter,” is headlined “Rethinking the Prospects of a Soft Landing.” The piece makes the case that the higher-than-expected January CPI, coupled with other data points, raises questions whether inflation is under control.

In making this case one section tells readers:

“Worry extends beyond the markets. The prospect of higher inflation is weighing on consumers and small-business owners.

“Meanwhile, Krispy Kreme, Coca-Cola and Heineken each warned this week that stubborn inflation could hurt their earnings.”

Just to say the obvious (I guess not obvious to Dealbook writers and editors), if these big consumer product companies are worried that they are going to be hurt by inflation, it means that they think they lack the pricing power to raise their prices further. As many have noted, part of the pandemic inflation story has been large companies taking advantage of their market power to jack up profit margins.

The story here, insofar as it is accurate, is that the economy has changed enough that big firms no longer have the pricing power they did one or two years ago. That is good news in the battle against inflation, not the bad news we are being told here.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

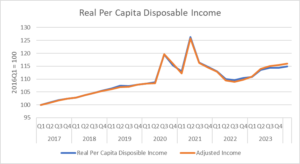

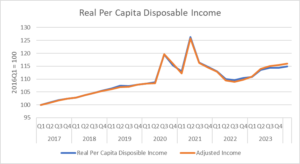

Nate Silver had a piece in the New York Times Monday arguing that people had good reason to be upset about the economy under Biden, and that it was not just perceptions that were out of touch with economic reality. Silver tells us:

“But it’s a mistake to assume that consumers have just been reacting to news accounts of high gasoline or fast-food prices instead of actually observing the impact on their bottom lines. People’s pocketbooks really aren’t in great shape — income growth has struggled to keep up with inflation.”

To make his point, he includes a graph of real (inflation-adjusted) per capita disposable income. This is a reasonable measure of people’s income, although it doesn’t quite show the story Silver claims. I have included the same graph but taken it back a bit further to the start of the Trump administration so that people can get a better sense of what is going on.

Source: NIPA Tables 2.1 and Table 1.7.5 and author’s calculations, see text.

As can be seen, there are big jumps in 2020 and 2021. These are primarily due to the pandemic checks that we got, first in the CARES Acts, passed while Trump was still president, but then a second round of $1,400 a person after Biden’s recovery package took effect. Income was also boosted by other pandemic relief programs such as expanded unemployment benefits and the expanded child tax credit.

These programs mostly went away after 2021, which explains most of the drop in 2022. That was also a year of sharp inflation, which outpaced wage growth for most workers. That further lowered real income.

However, we see a reversal in 2023. Wages substantially outpace inflation for the year. In addition, the rapid pace of job creation meant that a larger share of the population was working. As a result, real disposable income was considerably higher in the 4th quarter of 2023 than in the 4th quarter of 2019, before the pandemic hit.

To be precise, real per capita disposable income was 6.0 percent higher in the 4th quarter of 2023 than in the fourth quarter of 2019. We can debate what “struggled to keep pace with inflation means,” but we can also do a simple comparison. Between the 4th quarter of 2016, before Trump took office, and the 4th quarter of 2019, real per capita disposable income rose by 8.3 percent.

Now, 8.3 percent is obviously larger than 6.0 percent, and we’re looking at three years rather than four, but it is hard to believe that 6.0 percent growth over four years is serious hardship, while 8.0 percent over three years is great. It is also worth noting in passing that we had a worldwide pandemic that, in addition to killing tens of millions of people, disrupted economies and led to inflation everywhere.

If people were willing to accept a pandemic excuse for the ten million extra unemployed workers at the end of the Trump administration, it seems they would be willing to buy that the pandemic may have slowed income growth somewhat. If not, that sounds more like a story of perceptions than reality.

In any case, there are some other factors that make the story of the Biden economy look better than the 6.0 percent growth figure. First, I have included an “adjusted” line for per capita disposable income alongside the line with the published data from the Bureau of Economic Analysis.

This adjustment takes account of the fact that there has been an unusual gap between measured GDP growth and measured growth in gross domestic income over the last couple of years. This is unusual since in principle we are measuring the same thing.

We can either measure GDP by adding up the goods and services produced, or we can add up the incomes generated in the production process (wages, profits, interest, etc.). The two numbers are never exactly the same, but they usually end up being pretty close.

In the last two years they have grown far apart, with GDP measured on the output side exceeding the income measure by 2.4 percent in the third quarter. (We don’t have fourth quarter data available yet, so I have assumed the same gap persisted into the fourth quarter.)

Revisions to the data usually bring the two measures closer in line, but given the data we have, it is normal to assume that the true figure will be somewhere in the middle. For my adjusted line, I assume that the true measure of GDP and income growth is halfway between the two reported measures. Making this assumption raises real per capita income growth under Biden to 7.0 percent. That is still less than under Trump but seems pretty far from a struggle to keep pace with inflation.

I’ll add two other important issues that are often overlooked in these discussions of living standards.

Mortgage Refinancing

There was a massive mortgage refinancing boom during the pandemic with 14 million households refinancing their mortgages. The New York Fed estimated that the 9 million households who refinanced without taking out additional money are saving an average of more than $2,500 a year.

The other five million took advantage of low interest rates and rising house prices to borrow more money against their home. The end of the refinancing boom brought an end to this channel of credit, leading to the increase in credit card debt that has gotten many analysts worried.

The savings on mortgage payments do not show up as an increase in disposable income in the GDP accounts. The reduction in mortgage interest payments translates into less interest income among lenders. However the lenders in this story tend to have higher income than the borrowers, so we might think this is in general a good story.

It is striking that this massive wave of refinancing is rarely mentioned in reporting on the economy, while the higher mortgage rates facing potential new home buyers are a frequent topic of reporting. There are many more people in the refinancing camp than potential first-time homebuyers.

Working from Home

There has been an explosion in the number of people working from home as an enduring effect of the pandemic. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, 38 million people worked from home on an average day last year. That’s an increase of more than 11 million from before the pandemic.

This is a huge benefit for these workers. The average amount of time spent commuting in 2019 was 27.6 minutes for a one-way trip, or 55.2 minutes for the round-trip. If we assume an eight-hour workday, time spent commuting added an average of 11.5 percent to the length of the workday. We can think of this as equivalent to an 11.5 percent reduction in the hourly pay rate, compared to a situation where no time is spent commuting.

Commuting to work doesn’t just take time, it is expensive. The average commuting distance to work is more than 15 miles. That means 30 miles for the round-trip. At the federal government’s mileage reimbursement rate of 62.5 cents per mile, this comes to $18.75 a day or almost $4,900 a year. That is 7.0 percent of the annual pay of a worker earning $70,000 a year.

It’s not just travel expenses that people save by being able to work at home. They can save on paying for business clothes, dry cleaning, and buying a purchased lunch at work. For many families, working from home may also save on childcare, insofar as they are able to care for young children without seriously disrupting their work.

In short, the option to work from home can mean large savings in time and money. Also avoiding traffic jams may mean a major quality of life improvement. It is true that the option to work from home is available primarily to the top half of earners, and especially the top fifth, but this is still a very large number that extends far beyond just the rich.

The Data Don’t Support the Complaints About the Economy

The basic story here is that we have seen improvement in living standards for most of the population during Biden’s term in office. Even if we just take Silver’s measure of real per capita disposable income, there were healthy gains, even if not as rapid as during the Trump presidency.

We have also seen substantial reductions in wage inequality in the Biden years. The wage gains were strongest at the bottom end of the wage distribution.

It seems implausible that anger about the economy can be based on the somewhat slower rate of income growth in the Biden year. This is especially the case when we consider that the economy was whacked by a worldwide pandemic, which ended up hurting other economies far more than the U.S.

The public was largely willing to forgive Trump for the high unemployment created by the pandemic, if it’s not willing to forgive Biden for its negative impact on the economy that reflects something other than objective reality. In other words, the media is failing to point out the impact of the pandemic on inflation and growth.

And the Silver measure of income does not include the gains to tens of millions of households from refinancing mortgages and the increased ability to work from home. We know from polling that people are not happy about the economy, but contrary to what Silver would have us believe, there is not a case for their unhappiness in the economic data.

Nate Silver had a piece in the New York Times Monday arguing that people had good reason to be upset about the economy under Biden, and that it was not just perceptions that were out of touch with economic reality. Silver tells us:

“But it’s a mistake to assume that consumers have just been reacting to news accounts of high gasoline or fast-food prices instead of actually observing the impact on their bottom lines. People’s pocketbooks really aren’t in great shape — income growth has struggled to keep up with inflation.”

To make his point, he includes a graph of real (inflation-adjusted) per capita disposable income. This is a reasonable measure of people’s income, although it doesn’t quite show the story Silver claims. I have included the same graph but taken it back a bit further to the start of the Trump administration so that people can get a better sense of what is going on.

Source: NIPA Tables 2.1 and Table 1.7.5 and author’s calculations, see text.

As can be seen, there are big jumps in 2020 and 2021. These are primarily due to the pandemic checks that we got, first in the CARES Acts, passed while Trump was still president, but then a second round of $1,400 a person after Biden’s recovery package took effect. Income was also boosted by other pandemic relief programs such as expanded unemployment benefits and the expanded child tax credit.

These programs mostly went away after 2021, which explains most of the drop in 2022. That was also a year of sharp inflation, which outpaced wage growth for most workers. That further lowered real income.

However, we see a reversal in 2023. Wages substantially outpace inflation for the year. In addition, the rapid pace of job creation meant that a larger share of the population was working. As a result, real disposable income was considerably higher in the 4th quarter of 2023 than in the 4th quarter of 2019, before the pandemic hit.

To be precise, real per capita disposable income was 6.0 percent higher in the 4th quarter of 2023 than in the fourth quarter of 2019. We can debate what “struggled to keep pace with inflation means,” but we can also do a simple comparison. Between the 4th quarter of 2016, before Trump took office, and the 4th quarter of 2019, real per capita disposable income rose by 8.3 percent.

Now, 8.3 percent is obviously larger than 6.0 percent, and we’re looking at three years rather than four, but it is hard to believe that 6.0 percent growth over four years is serious hardship, while 8.0 percent over three years is great. It is also worth noting in passing that we had a worldwide pandemic that, in addition to killing tens of millions of people, disrupted economies and led to inflation everywhere.

If people were willing to accept a pandemic excuse for the ten million extra unemployed workers at the end of the Trump administration, it seems they would be willing to buy that the pandemic may have slowed income growth somewhat. If not, that sounds more like a story of perceptions than reality.

In any case, there are some other factors that make the story of the Biden economy look better than the 6.0 percent growth figure. First, I have included an “adjusted” line for per capita disposable income alongside the line with the published data from the Bureau of Economic Analysis.

This adjustment takes account of the fact that there has been an unusual gap between measured GDP growth and measured growth in gross domestic income over the last couple of years. This is unusual since in principle we are measuring the same thing.

We can either measure GDP by adding up the goods and services produced, or we can add up the incomes generated in the production process (wages, profits, interest, etc.). The two numbers are never exactly the same, but they usually end up being pretty close.

In the last two years they have grown far apart, with GDP measured on the output side exceeding the income measure by 2.4 percent in the third quarter. (We don’t have fourth quarter data available yet, so I have assumed the same gap persisted into the fourth quarter.)

Revisions to the data usually bring the two measures closer in line, but given the data we have, it is normal to assume that the true figure will be somewhere in the middle. For my adjusted line, I assume that the true measure of GDP and income growth is halfway between the two reported measures. Making this assumption raises real per capita income growth under Biden to 7.0 percent. That is still less than under Trump but seems pretty far from a struggle to keep pace with inflation.

I’ll add two other important issues that are often overlooked in these discussions of living standards.

Mortgage Refinancing

There was a massive mortgage refinancing boom during the pandemic with 14 million households refinancing their mortgages. The New York Fed estimated that the 9 million households who refinanced without taking out additional money are saving an average of more than $2,500 a year.

The other five million took advantage of low interest rates and rising house prices to borrow more money against their home. The end of the refinancing boom brought an end to this channel of credit, leading to the increase in credit card debt that has gotten many analysts worried.

The savings on mortgage payments do not show up as an increase in disposable income in the GDP accounts. The reduction in mortgage interest payments translates into less interest income among lenders. However the lenders in this story tend to have higher income than the borrowers, so we might think this is in general a good story.

It is striking that this massive wave of refinancing is rarely mentioned in reporting on the economy, while the higher mortgage rates facing potential new home buyers are a frequent topic of reporting. There are many more people in the refinancing camp than potential first-time homebuyers.

Working from Home

There has been an explosion in the number of people working from home as an enduring effect of the pandemic. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, 38 million people worked from home on an average day last year. That’s an increase of more than 11 million from before the pandemic.

This is a huge benefit for these workers. The average amount of time spent commuting in 2019 was 27.6 minutes for a one-way trip, or 55.2 minutes for the round-trip. If we assume an eight-hour workday, time spent commuting added an average of 11.5 percent to the length of the workday. We can think of this as equivalent to an 11.5 percent reduction in the hourly pay rate, compared to a situation where no time is spent commuting.

Commuting to work doesn’t just take time, it is expensive. The average commuting distance to work is more than 15 miles. That means 30 miles for the round-trip. At the federal government’s mileage reimbursement rate of 62.5 cents per mile, this comes to $18.75 a day or almost $4,900 a year. That is 7.0 percent of the annual pay of a worker earning $70,000 a year.

It’s not just travel expenses that people save by being able to work at home. They can save on paying for business clothes, dry cleaning, and buying a purchased lunch at work. For many families, working from home may also save on childcare, insofar as they are able to care for young children without seriously disrupting their work.

In short, the option to work from home can mean large savings in time and money. Also avoiding traffic jams may mean a major quality of life improvement. It is true that the option to work from home is available primarily to the top half of earners, and especially the top fifth, but this is still a very large number that extends far beyond just the rich.

The Data Don’t Support the Complaints About the Economy

The basic story here is that we have seen improvement in living standards for most of the population during Biden’s term in office. Even if we just take Silver’s measure of real per capita disposable income, there were healthy gains, even if not as rapid as during the Trump presidency.

We have also seen substantial reductions in wage inequality in the Biden years. The wage gains were strongest at the bottom end of the wage distribution.

It seems implausible that anger about the economy can be based on the somewhat slower rate of income growth in the Biden year. This is especially the case when we consider that the economy was whacked by a worldwide pandemic, which ended up hurting other economies far more than the U.S.

The public was largely willing to forgive Trump for the high unemployment created by the pandemic, if it’s not willing to forgive Biden for its negative impact on the economy that reflects something other than objective reality. In other words, the media is failing to point out the impact of the pandemic on inflation and growth.

And the Silver measure of income does not include the gains to tens of millions of households from refinancing mortgages and the increased ability to work from home. We know from polling that people are not happy about the economy, but contrary to what Silver would have us believe, there is not a case for their unhappiness in the economic data.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión