In the last-half century, productivity has outpaced the growth of real compensation for the median worker by more than 40 percent. This means that if workers’ pay had kept pace with productivity, as it did in the three decades after World War II, it would be roughly 40 percent higher than it is today.

This would mean that instead of a typical worker earning $34 an hour, they would be earning close to $48 an hour. That implies an annual wage of $96,000 a year for a worker putting in 40 hours a week for 50 weeks a year.

Getting workers their fair share should be, and to some extent has been, a central issue in political debates. However, there is a continual effort by the media to pull the focus away from within generation inequality, and instead tell young people that their problems stem from their parents and grandparents getting too much money from Social Security, Medicare, and other government programs.

The major media outlets love to highlight absurd stories of generational inequality, with baby boomers ripping off their children and grandchildren through Social Security and Medicare. A New York Times column by Gene Steurele and Glenn Kramon is the latest effort.

Their basic story here is that baby boomers are getting far more back from Social Security and Medicare than they paid into these programs. It turns out that this is not especially true, even by Steurele’s own calculation.

If we look at a lifetime average wage earner who turns 65 in 2025, Steurele and his co-author Karen Smith, calculate they will have paid Social Security taxes with a present value of $391,000 and will be getting back benefits with a present value of $394,000. If we move up the income scale to someone who earned the Social Security maximum (currently $160,000), the present value of taxes would be $953,000, compared to benefits of $634,000.

If we look at couples the story looks better for beneficiaries, especially one-earner couples (a rarity) and also for moderate-income workers. However, in a world where raising taxes on people earning less than $400k seems to be beyond the pale, I’m not sure too many politicians will be anxious to take away benefits from low-earning retirees.

Steurele and Smith find a much larger subsidy from Medicare. There are some technical issues here but the most important point is that the supposed “subsidy” is primarily due to the fact that we pay twice as much per person for our health care as people in other wealthy countries without having much to show in terms of better outcomes.

The reason is that we pay drug companies, medical equipment suppliers, doctors and other providers twice as much as in other wealthy countries. The subsidies really are for these actors in the healthcare industry, not for retirees.

Insofar as young people are having difficulty getting ahead the problem is all the money going to people at the top end of the income distribution. The money going to retirees for Social Security and Medicare is a trivial part of this story, regardless of how much the NYT wants to tell us otherwise.

In the last-half century, productivity has outpaced the growth of real compensation for the median worker by more than 40 percent. This means that if workers’ pay had kept pace with productivity, as it did in the three decades after World War II, it would be roughly 40 percent higher than it is today.

This would mean that instead of a typical worker earning $34 an hour, they would be earning close to $48 an hour. That implies an annual wage of $96,000 a year for a worker putting in 40 hours a week for 50 weeks a year.

Getting workers their fair share should be, and to some extent has been, a central issue in political debates. However, there is a continual effort by the media to pull the focus away from within generation inequality, and instead tell young people that their problems stem from their parents and grandparents getting too much money from Social Security, Medicare, and other government programs.

The major media outlets love to highlight absurd stories of generational inequality, with baby boomers ripping off their children and grandchildren through Social Security and Medicare. A New York Times column by Gene Steurele and Glenn Kramon is the latest effort.

Their basic story here is that baby boomers are getting far more back from Social Security and Medicare than they paid into these programs. It turns out that this is not especially true, even by Steurele’s own calculation.

If we look at a lifetime average wage earner who turns 65 in 2025, Steurele and his co-author Karen Smith, calculate they will have paid Social Security taxes with a present value of $391,000 and will be getting back benefits with a present value of $394,000. If we move up the income scale to someone who earned the Social Security maximum (currently $160,000), the present value of taxes would be $953,000, compared to benefits of $634,000.

If we look at couples the story looks better for beneficiaries, especially one-earner couples (a rarity) and also for moderate-income workers. However, in a world where raising taxes on people earning less than $400k seems to be beyond the pale, I’m not sure too many politicians will be anxious to take away benefits from low-earning retirees.

Steurele and Smith find a much larger subsidy from Medicare. There are some technical issues here but the most important point is that the supposed “subsidy” is primarily due to the fact that we pay twice as much per person for our health care as people in other wealthy countries without having much to show in terms of better outcomes.

The reason is that we pay drug companies, medical equipment suppliers, doctors and other providers twice as much as in other wealthy countries. The subsidies really are for these actors in the healthcare industry, not for retirees.

Insofar as young people are having difficulty getting ahead the problem is all the money going to people at the top end of the income distribution. The money going to retirees for Social Security and Medicare is a trivial part of this story, regardless of how much the NYT wants to tell us otherwise.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Yes, I am serious. The media have no intention of allowing the data to get in the way of their bad economy stories. So now that food prices have pretty much stopped rising, the Guardian is coming to the rescue to tell readers how they can cope with rising food prices.

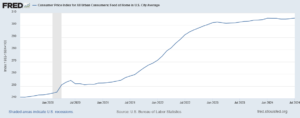

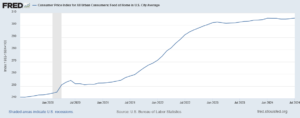

Here’s the picture on food prices over the last five years.

As can be seen, food prices did rise rapidly in 2021 and 2022, but then slowed sharply. In the last year and a half, they have risen by a total of just over one percent. This might have been a reasonable piece for the Guardian to have run in January of 2023, it does not make sense to run it now.

Yes, I am serious. The media have no intention of allowing the data to get in the way of their bad economy stories. So now that food prices have pretty much stopped rising, the Guardian is coming to the rescue to tell readers how they can cope with rising food prices.

Here’s the picture on food prices over the last five years.

As can be seen, food prices did rise rapidly in 2021 and 2022, but then slowed sharply. In the last year and a half, they have risen by a total of just over one percent. This might have been a reasonable piece for the Guardian to have run in January of 2023, it does not make sense to run it now.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

E.J. Dionne is a decent person and offers reasonable takes on most policy issues, but he really is enmeshed in the right’s view of the world. In the middle of a piece praising Vice-President Harris’ coalition building and economic agenda, Dionne tells readers:

“She champions the new economic consensus that President Joe Biden began to bring to life, replacing the view that markets alone, spurred by low taxes and deregulation, can save us.”

It is totally understandable that the right wants people to believe that “markets alone” were responsible for the massive upward redistribution of income of the last half century. But it happens to be total crap.

Starting with my favorite, government-granted patent and copyright monopolies are not “markets alone.” This concept is apparently hard for people who write in elite media outlets to understand.

The market alone does not threaten to arrest people who make copies of Pfizer’s Covid boosters without its permission or Ozempic without the permission of Novo Nordisk. Nor does the market alone threaten to arrest people who make copies of Microsoft’s software without Bill Gates’ permission.

Patent and copyright monopolies are the GOVERNMENT. Again, it’s understandable that the rich people who benefit from these government-granted monopolies like to pretend this is just the free market. It sounds much better to say “I’m rich and you’re poor because my skills are more valued by the market,” than “I’m rich and you’re poor because I rigged the market to give me all the money.” But why does an ostensibly liberal columnist go along with this blatant lie?

And there is huge money at stake here. In the case of prescription drugs and other pharmaceutical products alone we will pay over $650 billion a year for items that would likely cost us less than $100 billion in a FREE MARKET (see Line 121). If we add in the higher prices we pay for medical equipment, computers, software, and other items where these government-granted monopolies are a large share of the price, we are almost certainly well over $1 trillion a year and possibly close to $1.5 trillion. This would be roughly half of after-tax corporate profits. (See chapter 5 of Rigged [it’s free].)

These inflation-causing monopolies are far from the only way the government intervenes in the economy to make the rich richer. The supposed “free trade” deals of the last four decades all included provisions that required our trading partners to make these monopolies longer and stronger in their own countries.

The “free trade” deals also did little or nothing to reduce barriers to trade in highly paid professional services like physicians’ services or dentists’ services. As a result, these professionals get paid more than twice as much as their counterparts in other wealthy countries, even though our manufacturing workers get paid less. Again, we get why the winners want to call it “free trade,” but that is a lie.

Bailing out the big financial institutions when they did themselves in by their own greed and incompetence in the housing crash and more recently with the run-up in interest rates was also not “the market.” Many of the very rich got their hundreds of millions or billions as a result of the government’s coddling of the financial industry. Why don’t we call out the government assistance instead of pretending it is the free market?

Similarly, our CEOs get paid many times more than their counterparts in Europe or Japan. That’s not because they are smarter or harder working, it’s because we have a corrupt corporate government structure that largely allows top management to set their own pay and rip-off the companies they work for. If it’s too complicated for our great intellectuals, the market did not write the rules of corporate governance.

To take one more example, the market did not give us Section 230 which protects Mark Zuckerberg and Elon Musk from being held liable for spreading defamatory material in the same way that the New York Times or CNN is held liable.

I could go on, but the point should be obvious to anyone who does not write columns for a leading news outlet, the government has rigged the deck. Extreme inequality is not the result of a free market, it is a result of how the government has structured the market.

The market is just a tool, like the wheel. It makes as much sense to rant against the free market as to complain about the wheel. Unfortunately, the right has managed to get the bulk of the left in this country screaming at the wheel. As long as that remains the case, it will be difficult to make much progress in reducing inequality.

E.J. Dionne is a decent person and offers reasonable takes on most policy issues, but he really is enmeshed in the right’s view of the world. In the middle of a piece praising Vice-President Harris’ coalition building and economic agenda, Dionne tells readers:

“She champions the new economic consensus that President Joe Biden began to bring to life, replacing the view that markets alone, spurred by low taxes and deregulation, can save us.”

It is totally understandable that the right wants people to believe that “markets alone” were responsible for the massive upward redistribution of income of the last half century. But it happens to be total crap.

Starting with my favorite, government-granted patent and copyright monopolies are not “markets alone.” This concept is apparently hard for people who write in elite media outlets to understand.

The market alone does not threaten to arrest people who make copies of Pfizer’s Covid boosters without its permission or Ozempic without the permission of Novo Nordisk. Nor does the market alone threaten to arrest people who make copies of Microsoft’s software without Bill Gates’ permission.

Patent and copyright monopolies are the GOVERNMENT. Again, it’s understandable that the rich people who benefit from these government-granted monopolies like to pretend this is just the free market. It sounds much better to say “I’m rich and you’re poor because my skills are more valued by the market,” than “I’m rich and you’re poor because I rigged the market to give me all the money.” But why does an ostensibly liberal columnist go along with this blatant lie?

And there is huge money at stake here. In the case of prescription drugs and other pharmaceutical products alone we will pay over $650 billion a year for items that would likely cost us less than $100 billion in a FREE MARKET (see Line 121). If we add in the higher prices we pay for medical equipment, computers, software, and other items where these government-granted monopolies are a large share of the price, we are almost certainly well over $1 trillion a year and possibly close to $1.5 trillion. This would be roughly half of after-tax corporate profits. (See chapter 5 of Rigged [it’s free].)

These inflation-causing monopolies are far from the only way the government intervenes in the economy to make the rich richer. The supposed “free trade” deals of the last four decades all included provisions that required our trading partners to make these monopolies longer and stronger in their own countries.

The “free trade” deals also did little or nothing to reduce barriers to trade in highly paid professional services like physicians’ services or dentists’ services. As a result, these professionals get paid more than twice as much as their counterparts in other wealthy countries, even though our manufacturing workers get paid less. Again, we get why the winners want to call it “free trade,” but that is a lie.

Bailing out the big financial institutions when they did themselves in by their own greed and incompetence in the housing crash and more recently with the run-up in interest rates was also not “the market.” Many of the very rich got their hundreds of millions or billions as a result of the government’s coddling of the financial industry. Why don’t we call out the government assistance instead of pretending it is the free market?

Similarly, our CEOs get paid many times more than their counterparts in Europe or Japan. That’s not because they are smarter or harder working, it’s because we have a corrupt corporate government structure that largely allows top management to set their own pay and rip-off the companies they work for. If it’s too complicated for our great intellectuals, the market did not write the rules of corporate governance.

To take one more example, the market did not give us Section 230 which protects Mark Zuckerberg and Elon Musk from being held liable for spreading defamatory material in the same way that the New York Times or CNN is held liable.

I could go on, but the point should be obvious to anyone who does not write columns for a leading news outlet, the government has rigged the deck. Extreme inequality is not the result of a free market, it is a result of how the government has structured the market.

The market is just a tool, like the wheel. It makes as much sense to rant against the free market as to complain about the wheel. Unfortunately, the right has managed to get the bulk of the left in this country screaming at the wheel. As long as that remains the case, it will be difficult to make much progress in reducing inequality.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Yes folks, like other major news outlets the Washington Post is perfectly happy to ignore the data to tell you the economy is bad under Biden. Past entries in this series included the many pieces telling us young people have given up ever being able to own a home, even though the number of young people who are homeowners is considerably higher than before the pandemic, the CNN classic telling us about the retirement crisis even though the net worth of near retirees is up almost 50 percent from 2019, and the Washington Post and New York Times pieces telling us new college grads couldn’t find jobs even though their unemployment rate is near a twenty year low.

The media are absolutely determined to tell everyone the economy is awful in spite of the longest stretch of low unemployment in more than 70 years, healthy real wage growth, especially at the bottom, in spite of the pandemic, and record levels of job satisfaction. The media will not be deterred by good news in its effort to tell its audience that the Biden-Harris economy is awful.

Today’s entry in the data be damned awful Biden economy saga is an opinion piece that tells us in its title, “A big problem for young workers: 70- and 80-year-olds who won’t retire.” The story is that younger workers are being blocked in their career paths by old-timers who refuse to retire. (The observant ones out there might recall that we were supposed to be bothered by the flood of retirees who had to be supported by younger people still in the workforce. Oh well, both situations are awful.)

Anyhow, the punch line in the piece is a graph that purportedly shows an increase in the ratio of the wages of older workers to younger workers. The problem is the graph actually doesn’t show a continual increase in the ratio of the pay of older workers to younger workers.

It does show a rise from the 1970s until around 2010. It then levels off and then has trended down slightly from 2012 until 2018, which is the last year in graph. At that point, it was roughly back to its 2000 level.

There may have been a story in these data, but that was a decade ago when the ratio was peaking. It is more than a bit bizarre that the Washington Post would choose to highlight this trend now. But when you have an economy that is doing great by almost every standard measure, I guess it’s necessary to dig deep to tell the bad economy story. The Washington Post deserves a big hand MAGA for this one!

Yes folks, like other major news outlets the Washington Post is perfectly happy to ignore the data to tell you the economy is bad under Biden. Past entries in this series included the many pieces telling us young people have given up ever being able to own a home, even though the number of young people who are homeowners is considerably higher than before the pandemic, the CNN classic telling us about the retirement crisis even though the net worth of near retirees is up almost 50 percent from 2019, and the Washington Post and New York Times pieces telling us new college grads couldn’t find jobs even though their unemployment rate is near a twenty year low.

The media are absolutely determined to tell everyone the economy is awful in spite of the longest stretch of low unemployment in more than 70 years, healthy real wage growth, especially at the bottom, in spite of the pandemic, and record levels of job satisfaction. The media will not be deterred by good news in its effort to tell its audience that the Biden-Harris economy is awful.

Today’s entry in the data be damned awful Biden economy saga is an opinion piece that tells us in its title, “A big problem for young workers: 70- and 80-year-olds who won’t retire.” The story is that younger workers are being blocked in their career paths by old-timers who refuse to retire. (The observant ones out there might recall that we were supposed to be bothered by the flood of retirees who had to be supported by younger people still in the workforce. Oh well, both situations are awful.)

Anyhow, the punch line in the piece is a graph that purportedly shows an increase in the ratio of the wages of older workers to younger workers. The problem is the graph actually doesn’t show a continual increase in the ratio of the pay of older workers to younger workers.

It does show a rise from the 1970s until around 2010. It then levels off and then has trended down slightly from 2012 until 2018, which is the last year in graph. At that point, it was roughly back to its 2000 level.

There may have been a story in these data, but that was a decade ago when the ratio was peaking. It is more than a bit bizarre that the Washington Post would choose to highlight this trend now. But when you have an economy that is doing great by almost every standard measure, I guess it’s necessary to dig deep to tell the bad economy story. The Washington Post deserves a big hand MAGA for this one!

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

I don’t have time to do an exhaustive analysis of the implication of the downward revisions to the jobs numbers today, but I will make a few quick points.

First, the people complaining that this downward revision exposes cooked jobs data in prior months need to get their heads screwed on straight. Let’s just try a little logic here.

If the Biden-Harris administration had the ability to cook the job numbers, do we think they are too stupid to realize that they should keep cooking them at least through November? Seriously, do we think they are total morons? If you’ve been cooking the numbers for twenty months, wouldn’t you keep cooking them until Election Day?

Okay, but getting more serious here, the staff of the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) is a professional outfit that does exactly what we want it to do. They produce the data about the economy as best they can in a completely objective way. And they use methods that are completely transparent.

People can go to the BLS website and read as much as they like about the nature of the survey that produces the monthly jobs number and large revision we saw today. The basic story is that the monthly survey goes to hundreds of thousands of employers who are supposed to be representative of the millions of employers in the economy. Generally, the survey gives us a pretty accurate job count, but it will never be exact.

Every year the BLS adjusts the data from the survey based on state unemployment insurance (UI) filings which have data from nearly every employer in the country. These UI filings are a near census for all payroll employment. If the UI data gives a different picture than the survey of employers, then the filings are almost certainly right and BLS revises it data accordingly.

For reasons that we can only speculate about, there was an unusually large gap this year. Many economists and statisticians will spend many hours trying to figure out why this is the case. But one thing we should be confident of is that no one cooked the data. BLS did the best they could in structuring their survey of employers. If they can find ways to improve it, they will, as they have in the past.

What Does This Tell Us About the Economy?

Turning briefly to the substance of the revision, I realize many people will be quick to say that this is bad news for our picture of the economy. That is not clear at all.

First, we should be clear that even with the revision the economy still created jobs at a very rapid pace in the period covered, from March 2023 to March 2024. While BLS had previously reported that we created 2.9 million jobs over this period, or 242,000 a month. The revision means we created 2.1 million jobs or 172,000 jobs a month. By comparison, in the three years prior to the onset of the pandemic, we created jobs at a rate of 179,000 a month. Even with the downward revision, we were still creating jobs at a very healthy pace.

To put these numbers in a larger context, it is necessary to have a broader picture of the labor market. Every month we look at two independent surveys in the BLS Employment Report. One is the establishment survey which will be revised based on today’s report from the UI filings. The other is the survey of households, the Current Population Survey (CPS), which tells us the percentage of the workforce that is employed and unemployed.

The CPS also has a measure of employment, but we generally pay it much less attention, since on a monthly basis it is highly erratic. For example, in October of 2017, when the economy seemed to be growing at a healthy pace, the CPS showed a loss of 677,000 jobs. It is implausible there actually was a job loss anything like that in the month, just as it was implausible there was a job gain like the 783,000 reported for the prior month.

Over longer periods of time, the erratic jumps and plunges tend to average out, but even here there are problems. The CPS gives us ratios for the percent of people who are employed and unemployed and the characteristics of their employment, such as whether their job is full-time or part-time, the industry they are employed in, their race, gender, education, and other factors.

However, the total employment figure depends on population controls that come indirectly from the decennial Census. The population controls take the total number of people found in the Census and then adjust based on estimates of births, deaths, immigration, and emigration. This process is imperfect and can often lead to large errors.

For example, at the end of the decade of the 1990s, more than two million people were added into the population controls for the survey because of an underestimate of population growth in the decade. In recent years, the employment growth in the CPS has seriously lagged job growth in the CES. This is true even after today’s downward revision to the CES.

The most plausible explanation for the large gap between the two surveys is that the population controls are underestimating the impact of immigration. A recent paper from the Brookings Institution calculates that undercounting immigration may have led the CPS to understate employment growth by more than 1 million a year.

While we may not be able to use the CPS to get a more accurate count of the actual number of jobs generated by the economy, what it does give us is actually more important. It tells us the share of the population that is employed, unemployed, employed part-time, and even gives us data on wages.

These factors are more important because these factors tell us more directly how well people are doing. The number of jobs in itself doesn’t answer that question. It is not like runs in a baseball game. We care about jobs because people who want to work should be able to get a job. If it turns out that we are generated somewhat fewer jobs than we thought, but most people who want jobs have jobs, then this is a pretty good story.

That looks like the situation today. The unemployment rate was 4.3 percent in July. That is higher than the 3.4 percent low hit in April of last year, but it is still quite low by historical standards. It was only this low for three months of the George W. Bush administration, it only got down to 4.3 percent or lower for the last two years of the late 1990s boom. It never got close to 4.3 percent during the Reagan “boom” years.

To be clear, the rise in the unemployment rate since last April is cause for concern. If that continues, unemployment will definitely be a serious issue. But if we just take the snapshot for the unemployment rate for July of this year, it is hard to see much cause for complaint.

We can also flip this over and ask the opposite question of what share of the population is employed. Here we have a very good story. If we look at the prime age population, people between the ages of 25 and 54, the employment to population ratio stood at 80.9 percent in July. We would have to go back to April of 2001 to find a higher rate.

It is reasonable to look at prime-age employment to control for the effect of the aging of the population. Most of us would not consider it a bad thing that people in their sixties and seventies opt to retire rather than work. As the huge baby boom cohorts age, we are seeing a growing share of the population in retirement. Looking just at the prime age population allows us to see the share of the population that we think would want to work, who can actually get jobs.

We can also look at other factors like the share of the population who are working part-time, but want full-time jobs, which is now very low. And we can look at the growth rate of real wages (wages adjusted for higher prices), which has been good overall and especially for those at the lower end of the wage distribution.

How Do the Revisions Change the Economic Picture?

Nothing about the revisions to the CES change the story of an economy where jobs are relatively plentiful, and workers are seeing wage increases in excess of inflation. What they tell us is that the economy is creating fewer jobs than we had previously believed. But if we have high levels of employment with fewer jobs, what exactly is the problem?

In fact, there is a very positive side to this story. Assuming that we have accurately measured output (there are issues here too), if we generated this output with fewer jobs than we had previously estimated, this means productivity growth has been faster than had previously been estimated.

Productivity growth is the change in output per hour of work. If the economy created fewer jobs than we thought, then the growth in hours of work was less than we had previously believed. This means that productivity growth was stronger than had been reported.

This is a big deal since productivity growth ultimately determines how rapidly living standards can improve. There are huge issues of distribution, and also measurement (much of what affects living standards will not be picked up in productivity), but if productivity is growing at a 2.0 percent annual rate, this means that we can in principle see more rapid gains in living standards than if it is growing at just a 1.5 percent annual rate.

The one-year change doesn’t matter much, but over time this difference is substantial. In the case of a gap between a 2.0 percent growth rate versus a 1.5 percent growth rate, after a decade it would be almost 6.0 percent. For a worker near the median wage this would be the difference between taking home $53,000 a year versus $50,000 a year.

After 20 years, the gap would grow to almost 14 percent. This would amount to a wage gap of close to $7,000 for a worker earning near the median annual wage.

The lower job growth resulting from the revisions today would imply that hours grew by 0.5 percent less from the first quarter of 2023 to the first quarter of 2024. Productivity growth for this period is currently reported as 2.9 percent. A reduction in hours growth of 0.5 percent would mean that productivity growth is 0.5 percentage points faster than had been reported, or 3.4 percent over this period.

Before celebrating this extraordinary rate of productivity growth (we had averaged just 1.1 percent in the decade prior to the pandemic) it is important to realize that the data are highly erratic, especially in the period following the pandemic. Productivity had actually fallen 0.5 percent in the prior year.

So, it’s far too early to celebrate a pickup in productivity growth, but the downward revision to hours growth implied by today’s revision to the jobs data unambiguously raises the pace of productivity growth over the last year. In that sense, it is good news. But as with all economic data, it’s part of a big picture, and we can’t make too much of any specific data release in isolation.

Take Away from Revision—More Fears of Weakness and Hope for Faster Productivity

The rise in unemployment since its recovery low has caused many to fear a new recession. This is definitely a cause for concern, but most other data, including very current data on items like road and air travel and restaurant reservations, do not give evidence of a recession. Nonetheless, the report showing that we were creating jobs at a slower pace than previously reported, albeit still very rapid, points in the direction of weakness.

On the other hand, the revision is encouraging in that it bolsters the case for a productivity upturn. It is far too early to declare the upturn is here, but it’s great to get another data point in the right direction. For this reason, the slower job growth indicated by this revision should be seen as more good than bad.

I don’t have time to do an exhaustive analysis of the implication of the downward revisions to the jobs numbers today, but I will make a few quick points.

First, the people complaining that this downward revision exposes cooked jobs data in prior months need to get their heads screwed on straight. Let’s just try a little logic here.

If the Biden-Harris administration had the ability to cook the job numbers, do we think they are too stupid to realize that they should keep cooking them at least through November? Seriously, do we think they are total morons? If you’ve been cooking the numbers for twenty months, wouldn’t you keep cooking them until Election Day?

Okay, but getting more serious here, the staff of the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) is a professional outfit that does exactly what we want it to do. They produce the data about the economy as best they can in a completely objective way. And they use methods that are completely transparent.

People can go to the BLS website and read as much as they like about the nature of the survey that produces the monthly jobs number and large revision we saw today. The basic story is that the monthly survey goes to hundreds of thousands of employers who are supposed to be representative of the millions of employers in the economy. Generally, the survey gives us a pretty accurate job count, but it will never be exact.

Every year the BLS adjusts the data from the survey based on state unemployment insurance (UI) filings which have data from nearly every employer in the country. These UI filings are a near census for all payroll employment. If the UI data gives a different picture than the survey of employers, then the filings are almost certainly right and BLS revises it data accordingly.

For reasons that we can only speculate about, there was an unusually large gap this year. Many economists and statisticians will spend many hours trying to figure out why this is the case. But one thing we should be confident of is that no one cooked the data. BLS did the best they could in structuring their survey of employers. If they can find ways to improve it, they will, as they have in the past.

What Does This Tell Us About the Economy?

Turning briefly to the substance of the revision, I realize many people will be quick to say that this is bad news for our picture of the economy. That is not clear at all.

First, we should be clear that even with the revision the economy still created jobs at a very rapid pace in the period covered, from March 2023 to March 2024. While BLS had previously reported that we created 2.9 million jobs over this period, or 242,000 a month. The revision means we created 2.1 million jobs or 172,000 jobs a month. By comparison, in the three years prior to the onset of the pandemic, we created jobs at a rate of 179,000 a month. Even with the downward revision, we were still creating jobs at a very healthy pace.

To put these numbers in a larger context, it is necessary to have a broader picture of the labor market. Every month we look at two independent surveys in the BLS Employment Report. One is the establishment survey which will be revised based on today’s report from the UI filings. The other is the survey of households, the Current Population Survey (CPS), which tells us the percentage of the workforce that is employed and unemployed.

The CPS also has a measure of employment, but we generally pay it much less attention, since on a monthly basis it is highly erratic. For example, in October of 2017, when the economy seemed to be growing at a healthy pace, the CPS showed a loss of 677,000 jobs. It is implausible there actually was a job loss anything like that in the month, just as it was implausible there was a job gain like the 783,000 reported for the prior month.

Over longer periods of time, the erratic jumps and plunges tend to average out, but even here there are problems. The CPS gives us ratios for the percent of people who are employed and unemployed and the characteristics of their employment, such as whether their job is full-time or part-time, the industry they are employed in, their race, gender, education, and other factors.

However, the total employment figure depends on population controls that come indirectly from the decennial Census. The population controls take the total number of people found in the Census and then adjust based on estimates of births, deaths, immigration, and emigration. This process is imperfect and can often lead to large errors.

For example, at the end of the decade of the 1990s, more than two million people were added into the population controls for the survey because of an underestimate of population growth in the decade. In recent years, the employment growth in the CPS has seriously lagged job growth in the CES. This is true even after today’s downward revision to the CES.

The most plausible explanation for the large gap between the two surveys is that the population controls are underestimating the impact of immigration. A recent paper from the Brookings Institution calculates that undercounting immigration may have led the CPS to understate employment growth by more than 1 million a year.

While we may not be able to use the CPS to get a more accurate count of the actual number of jobs generated by the economy, what it does give us is actually more important. It tells us the share of the population that is employed, unemployed, employed part-time, and even gives us data on wages.

These factors are more important because these factors tell us more directly how well people are doing. The number of jobs in itself doesn’t answer that question. It is not like runs in a baseball game. We care about jobs because people who want to work should be able to get a job. If it turns out that we are generated somewhat fewer jobs than we thought, but most people who want jobs have jobs, then this is a pretty good story.

That looks like the situation today. The unemployment rate was 4.3 percent in July. That is higher than the 3.4 percent low hit in April of last year, but it is still quite low by historical standards. It was only this low for three months of the George W. Bush administration, it only got down to 4.3 percent or lower for the last two years of the late 1990s boom. It never got close to 4.3 percent during the Reagan “boom” years.

To be clear, the rise in the unemployment rate since last April is cause for concern. If that continues, unemployment will definitely be a serious issue. But if we just take the snapshot for the unemployment rate for July of this year, it is hard to see much cause for complaint.

We can also flip this over and ask the opposite question of what share of the population is employed. Here we have a very good story. If we look at the prime age population, people between the ages of 25 and 54, the employment to population ratio stood at 80.9 percent in July. We would have to go back to April of 2001 to find a higher rate.

It is reasonable to look at prime-age employment to control for the effect of the aging of the population. Most of us would not consider it a bad thing that people in their sixties and seventies opt to retire rather than work. As the huge baby boom cohorts age, we are seeing a growing share of the population in retirement. Looking just at the prime age population allows us to see the share of the population that we think would want to work, who can actually get jobs.

We can also look at other factors like the share of the population who are working part-time, but want full-time jobs, which is now very low. And we can look at the growth rate of real wages (wages adjusted for higher prices), which has been good overall and especially for those at the lower end of the wage distribution.

How Do the Revisions Change the Economic Picture?

Nothing about the revisions to the CES change the story of an economy where jobs are relatively plentiful, and workers are seeing wage increases in excess of inflation. What they tell us is that the economy is creating fewer jobs than we had previously believed. But if we have high levels of employment with fewer jobs, what exactly is the problem?

In fact, there is a very positive side to this story. Assuming that we have accurately measured output (there are issues here too), if we generated this output with fewer jobs than we had previously estimated, this means productivity growth has been faster than had previously been estimated.

Productivity growth is the change in output per hour of work. If the economy created fewer jobs than we thought, then the growth in hours of work was less than we had previously believed. This means that productivity growth was stronger than had been reported.

This is a big deal since productivity growth ultimately determines how rapidly living standards can improve. There are huge issues of distribution, and also measurement (much of what affects living standards will not be picked up in productivity), but if productivity is growing at a 2.0 percent annual rate, this means that we can in principle see more rapid gains in living standards than if it is growing at just a 1.5 percent annual rate.

The one-year change doesn’t matter much, but over time this difference is substantial. In the case of a gap between a 2.0 percent growth rate versus a 1.5 percent growth rate, after a decade it would be almost 6.0 percent. For a worker near the median wage this would be the difference between taking home $53,000 a year versus $50,000 a year.

After 20 years, the gap would grow to almost 14 percent. This would amount to a wage gap of close to $7,000 for a worker earning near the median annual wage.

The lower job growth resulting from the revisions today would imply that hours grew by 0.5 percent less from the first quarter of 2023 to the first quarter of 2024. Productivity growth for this period is currently reported as 2.9 percent. A reduction in hours growth of 0.5 percent would mean that productivity growth is 0.5 percentage points faster than had been reported, or 3.4 percent over this period.

Before celebrating this extraordinary rate of productivity growth (we had averaged just 1.1 percent in the decade prior to the pandemic) it is important to realize that the data are highly erratic, especially in the period following the pandemic. Productivity had actually fallen 0.5 percent in the prior year.

So, it’s far too early to celebrate a pickup in productivity growth, but the downward revision to hours growth implied by today’s revision to the jobs data unambiguously raises the pace of productivity growth over the last year. In that sense, it is good news. But as with all economic data, it’s part of a big picture, and we can’t make too much of any specific data release in isolation.

Take Away from Revision—More Fears of Weakness and Hope for Faster Productivity

The rise in unemployment since its recovery low has caused many to fear a new recession. This is definitely a cause for concern, but most other data, including very current data on items like road and air travel and restaurant reservations, do not give evidence of a recession. Nonetheless, the report showing that we were creating jobs at a slower pace than previously reported, albeit still very rapid, points in the direction of weakness.

On the other hand, the revision is encouraging in that it bolsters the case for a productivity upturn. It is far too early to declare the upturn is here, but it’s great to get another data point in the right direction. For this reason, the slower job growth indicated by this revision should be seen as more good than bad.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

A couple of decades ago a candidate for Copenhagen’s city council ran on a platform that if he won, the wind would always be at bicycle riders’ backs. In a country where many people use bicycles for commuting and shopping, this was an attractive promise. The proposal was put forward as a joke by a comedian running a farcical campaign for office. In the U.S., the media would likely have taken the idea seriously.

This is pretty much what we have in the continuing drumbeat of inflation stories where reporters acknowledge that inflation has fallen back to its pre-pandemic pace, but then tell us that “prices are still high.” While we would all like to pay less money for food, clothes, and other items, wages are 23 percent higher than before the pandemic. (Prices have risen 20 percent.) The idea that prices will somehow fall back to where they were four and a half years ago makes about as much sense as saying the wind will always be at bicycle riders’ back.

To be clear, there is some room for price declines or at least for inflation to lag wages by more than usual. Profit margins did increase in the pandemic, and it would be reasonable to expect that margins would shrink as the economy returns to normal. But the reduction in margins would be reducing prices by 1-2 percentage points, not returning prices to their pre-pandemic levels or anything close to them. (There may be larger declines for some items.)

The real question is why would people come to believe that something so obviously absurd is plausible? I’m sure that no one in Copenhagen went to the polls thinking that the comedian candidate was going to ensure that the wind was always at their back, why do people in the United States somehow think it makes sense that prices would fall back to their pre-pandemic level?

I can’t monitor people’s thought processes, but I do remember back to our last serious bought of inflation in the 1970s and 1980s. I do not recall anyone discussing the idea that prices would fall back to the levels they were at before inflation took off.

I’m sure there were some number of people in the country who thought something like that, but if a reporter doing a person on the street interview came across them, they likely would have thanked them for their opinion and gone on to find someone with a minimal grasp of economics. Then, as now, it simply was not plausible that prices were going to fall back to some prior level, in the absence of a catastrophic depression that sent wages tumbling. Since that was not in the cards, and almost no one wanted to see a catastrophic depression, public discussion focused on getting the rate of inflation down to an acceptable level.

However, that has not been the story of coverage of inflation under Biden. When inflation was high in 2021 and 2022 reporters anxiously highlighted the situations of people who consumed extraordinary amounts of whatever item (e.g. milk and gas) was rising rapidly in price. They also rarely mentioned government programs, like the expanded child tax credit, which would substantially or completely offset the impact of higher prices.

As inflation has come down and wage growth again outpaced prices the media have fixated on the assertion that people are upset that prices have not come back down. I assume that no one who reports on politics for a major media outlet is so ignorant to think that this is a plausible story. The question then is why do they keep feeding it by repeating the complaint endlessly like it is a serious way to talk about the economy?

We then get political figures like President Biden and Vice-President Harris who are pressed on why they can’t do the impossible. I suppose it would be bad politics, but they really should tell any reporter posing a question about prices still being high to go learn a little bit of economics and then come back and ask a more serious question.

Unfortunately, the media are dominated by unserious reporters who ask unserious questions which gives us an absurd national debate about bringing about the impossible. If the Danish comedian had run for office here, given the state of our media, he might have won.

A couple of decades ago a candidate for Copenhagen’s city council ran on a platform that if he won, the wind would always be at bicycle riders’ backs. In a country where many people use bicycles for commuting and shopping, this was an attractive promise. The proposal was put forward as a joke by a comedian running a farcical campaign for office. In the U.S., the media would likely have taken the idea seriously.

This is pretty much what we have in the continuing drumbeat of inflation stories where reporters acknowledge that inflation has fallen back to its pre-pandemic pace, but then tell us that “prices are still high.” While we would all like to pay less money for food, clothes, and other items, wages are 23 percent higher than before the pandemic. (Prices have risen 20 percent.) The idea that prices will somehow fall back to where they were four and a half years ago makes about as much sense as saying the wind will always be at bicycle riders’ back.

To be clear, there is some room for price declines or at least for inflation to lag wages by more than usual. Profit margins did increase in the pandemic, and it would be reasonable to expect that margins would shrink as the economy returns to normal. But the reduction in margins would be reducing prices by 1-2 percentage points, not returning prices to their pre-pandemic levels or anything close to them. (There may be larger declines for some items.)

The real question is why would people come to believe that something so obviously absurd is plausible? I’m sure that no one in Copenhagen went to the polls thinking that the comedian candidate was going to ensure that the wind was always at their back, why do people in the United States somehow think it makes sense that prices would fall back to their pre-pandemic level?

I can’t monitor people’s thought processes, but I do remember back to our last serious bought of inflation in the 1970s and 1980s. I do not recall anyone discussing the idea that prices would fall back to the levels they were at before inflation took off.

I’m sure there were some number of people in the country who thought something like that, but if a reporter doing a person on the street interview came across them, they likely would have thanked them for their opinion and gone on to find someone with a minimal grasp of economics. Then, as now, it simply was not plausible that prices were going to fall back to some prior level, in the absence of a catastrophic depression that sent wages tumbling. Since that was not in the cards, and almost no one wanted to see a catastrophic depression, public discussion focused on getting the rate of inflation down to an acceptable level.

However, that has not been the story of coverage of inflation under Biden. When inflation was high in 2021 and 2022 reporters anxiously highlighted the situations of people who consumed extraordinary amounts of whatever item (e.g. milk and gas) was rising rapidly in price. They also rarely mentioned government programs, like the expanded child tax credit, which would substantially or completely offset the impact of higher prices.

As inflation has come down and wage growth again outpaced prices the media have fixated on the assertion that people are upset that prices have not come back down. I assume that no one who reports on politics for a major media outlet is so ignorant to think that this is a plausible story. The question then is why do they keep feeding it by repeating the complaint endlessly like it is a serious way to talk about the economy?

We then get political figures like President Biden and Vice-President Harris who are pressed on why they can’t do the impossible. I suppose it would be bad politics, but they really should tell any reporter posing a question about prices still being high to go learn a little bit of economics and then come back and ask a more serious question.

Unfortunately, the media are dominated by unserious reporters who ask unserious questions which gives us an absurd national debate about bringing about the impossible. If the Danish comedian had run for office here, given the state of our media, he might have won.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

No one expects serious economic analysis from the Washington Post’s conservative columnists and Mark Theissen doesn’t let us down.

Theissen starts off by reminding of one of Larry Summers’ most embarrassing moments:

“Nonetheless, as president of the Senate, Harris cast the deciding vote to pass the catastrophically misnamed ‘American Rescue Plan’ with only Democratic votes — a reckless $1.9 trillion social spending bill that even former treasury secretary Lawrence H. Summers, who served in both the Clinton and Obama administrations, warned would ‘set off inflationary pressures of a kind we have not seen in a generation.’”

Summers almost certainly regrets this warning. He recently commented that the Biden-Harris administration has a “remarkable record” on the economy. Summers’ main concern was that we would get a wage-price spiral like we had in the 70s. This upward spiral only ended when the Fed pushed interest rates through the roof, and we got double-digit unemployment.

As it turned out, Summers was wrong. Inflation has largely fallen back to its pre-pandemic pace. We have not seen a wage-price spiral. While unemployment has risen from its 2023 low, its current 4.3 percent rate is still quite low by historical standards.

But this is only the beginning of Theissen’s shoddy economics. He tells readers that the saving rate has fallen to a near record low. Theissen actually can find support for this in the data, but only because he apparently does not understand it.

Saving is defined as the portion of household disposable income that is not consumed. In the last two years there has been a large gap between GDP as measured on the output side and GDP as measured on the income side. The two measures are by definition equal.

At this point, we don’t know which is close to the mark, but for calculating the saving rate it doesn’t matter. If output has been overstated that it almost certainly means consumption has been overstated. If true consumption is less than reported consumption then the saving rate is higher than is now reported.

On the other side, if income is understated then disposable income will be understated, which would also mean that the saving rate will be understated. When we adjust for this gap between output side GDP and income side GDP, the current saving rate is roughly the same as before the pandemic.

Theissen then tells us:

“Meanwhile, consumer debt has reached a record high of $17.8 trillion — a $3.15 trillion increase since Biden and Harris took office.”

The trick here is that, unless we are in a recession, household debt is almost always hitting record highs, as it did throughout the Trump administration, until the pandemic. Economists usually focus on net worth, which are assets minus debt, which is at a record high far above the pre-pandemic level.

He notes the rise in grocery prices, but somehow can’t get data on wage increases, which for production and non-supervisory workers have been roughly the same. Theissen also highlights the great economy when we were still in the pandemic recession and mortgage rates were low, but unemployment was high.

Anyhow, I realize no one expects serious economic analysis from Mark Theissen, and he didn’t let anyone down.

No one expects serious economic analysis from the Washington Post’s conservative columnists and Mark Theissen doesn’t let us down.

Theissen starts off by reminding of one of Larry Summers’ most embarrassing moments:

“Nonetheless, as president of the Senate, Harris cast the deciding vote to pass the catastrophically misnamed ‘American Rescue Plan’ with only Democratic votes — a reckless $1.9 trillion social spending bill that even former treasury secretary Lawrence H. Summers, who served in both the Clinton and Obama administrations, warned would ‘set off inflationary pressures of a kind we have not seen in a generation.’”

Summers almost certainly regrets this warning. He recently commented that the Biden-Harris administration has a “remarkable record” on the economy. Summers’ main concern was that we would get a wage-price spiral like we had in the 70s. This upward spiral only ended when the Fed pushed interest rates through the roof, and we got double-digit unemployment.

As it turned out, Summers was wrong. Inflation has largely fallen back to its pre-pandemic pace. We have not seen a wage-price spiral. While unemployment has risen from its 2023 low, its current 4.3 percent rate is still quite low by historical standards.

But this is only the beginning of Theissen’s shoddy economics. He tells readers that the saving rate has fallen to a near record low. Theissen actually can find support for this in the data, but only because he apparently does not understand it.

Saving is defined as the portion of household disposable income that is not consumed. In the last two years there has been a large gap between GDP as measured on the output side and GDP as measured on the income side. The two measures are by definition equal.

At this point, we don’t know which is close to the mark, but for calculating the saving rate it doesn’t matter. If output has been overstated that it almost certainly means consumption has been overstated. If true consumption is less than reported consumption then the saving rate is higher than is now reported.

On the other side, if income is understated then disposable income will be understated, which would also mean that the saving rate will be understated. When we adjust for this gap between output side GDP and income side GDP, the current saving rate is roughly the same as before the pandemic.

Theissen then tells us:

“Meanwhile, consumer debt has reached a record high of $17.8 trillion — a $3.15 trillion increase since Biden and Harris took office.”

The trick here is that, unless we are in a recession, household debt is almost always hitting record highs, as it did throughout the Trump administration, until the pandemic. Economists usually focus on net worth, which are assets minus debt, which is at a record high far above the pre-pandemic level.

He notes the rise in grocery prices, but somehow can’t get data on wage increases, which for production and non-supervisory workers have been roughly the same. Theissen also highlights the great economy when we were still in the pandemic recession and mortgage rates were low, but unemployment was high.

Anyhow, I realize no one expects serious economic analysis from Mark Theissen, and he didn’t let anyone down.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

In an effort to promote hysteria, the media have jumped on the proposals laid out by Vice-President Harris, telling their audience that they will increase the deficit by $1.7 trillion over the next decade. This estimate comes from the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget and includes a lot of guesswork, like the cost of Harris’ proposal for a first-time homebuyer tax credit, which is not well-defined at this point.

However, the key point here is that almost no one knows how much money $1.7 trillion is over the next decade. When the media present this figure, they are essentially telling their audience nothing.

It would take all of ten seconds to write this number in a way that would be meaningful to most people. GDP is projected to be $352 trillion over the next decade, so this sum will be a bit less than 0.5 percent of projected GDP. The country is projected to spend $84.9 trillion over this period, so Harris’ proposals would increase total spending by roughly 2.0 percent.

If the point is to inform their audience, it is hard to understand why the media would not take the few seconds needed to put large budget numbers in context. On the other hand, if the point is to promote fears of exploding deficits, they are going a good route.

In an effort to promote hysteria, the media have jumped on the proposals laid out by Vice-President Harris, telling their audience that they will increase the deficit by $1.7 trillion over the next decade. This estimate comes from the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget and includes a lot of guesswork, like the cost of Harris’ proposal for a first-time homebuyer tax credit, which is not well-defined at this point.

However, the key point here is that almost no one knows how much money $1.7 trillion is over the next decade. When the media present this figure, they are essentially telling their audience nothing.

It would take all of ten seconds to write this number in a way that would be meaningful to most people. GDP is projected to be $352 trillion over the next decade, so this sum will be a bit less than 0.5 percent of projected GDP. The country is projected to spend $84.9 trillion over this period, so Harris’ proposals would increase total spending by roughly 2.0 percent.

If the point is to inform their audience, it is hard to understand why the media would not take the few seconds needed to put large budget numbers in context. On the other hand, if the point is to promote fears of exploding deficits, they are going a good route.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The July Consumer Price Index report showed a slightly lower inflation rate than had generally been expected. Coupled with a good report on the Producer Price Index on Tuesday, it seems very likely the Federal Reserve Board will now begin cutting interest rates, as the inflation rate is approaching its 2.0 percent target.

In the face of what seems like unambiguously good economic news, NPR chose to feature two people who are struggling in the economy. This is a bit hard to understand.

There are always tens of millions of people who are struggling in the economy even in the best of times, but the recent news is that inflation is slowing sharply and real wages are rising. Why would this be a good opportunity to highlight people showing the opposite story. It might have been more reasonable to feature some of the record number of people traveling by air or taking vacations by car this summer.

This decision by NPR is similar to a decision by the New York Times, which chose on July 4th weekend to highlight an admittedly atypical worker to advance its claim that we are seeing an increasingly bifurcated economy. In fact, the data show the economy has been getting less bifurcated since the pandemic, with the lowest-paid workers experiencing extraordinarily rapid wage growth over the last four years.

To be clear, low-wage workers are still struggling. Even if their wages outpaced inflation by 10 percentage points over the last four years, they still would have difficulty making ends meet. It is just odd that major media outlets would choose to highlight their plight when they are doing relatively well rather than when they are doing relatively poorly.

The July Consumer Price Index report showed a slightly lower inflation rate than had generally been expected. Coupled with a good report on the Producer Price Index on Tuesday, it seems very likely the Federal Reserve Board will now begin cutting interest rates, as the inflation rate is approaching its 2.0 percent target.

In the face of what seems like unambiguously good economic news, NPR chose to feature two people who are struggling in the economy. This is a bit hard to understand.

There are always tens of millions of people who are struggling in the economy even in the best of times, but the recent news is that inflation is slowing sharply and real wages are rising. Why would this be a good opportunity to highlight people showing the opposite story. It might have been more reasonable to feature some of the record number of people traveling by air or taking vacations by car this summer.

This decision by NPR is similar to a decision by the New York Times, which chose on July 4th weekend to highlight an admittedly atypical worker to advance its claim that we are seeing an increasingly bifurcated economy. In fact, the data show the economy has been getting less bifurcated since the pandemic, with the lowest-paid workers experiencing extraordinarily rapid wage growth over the last four years.

To be clear, low-wage workers are still struggling. Even if their wages outpaced inflation by 10 percentage points over the last four years, they still would have difficulty making ends meet. It is just odd that major media outlets would choose to highlight their plight when they are doing relatively well rather than when they are doing relatively poorly.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The Trump campaign has made “drill everywhere” one of its main campaign slogans, implying that it will radically weaken environmental and other restrictions on oil drilling. This is supposed to be good for both the economy, since it would in principle mean lower gas and energy prices more generally, but also the oil industry since it won’t have to worry about government regulations in deciding where and how to drill. Increased oil production would be bad news for the environment since it likely means more local contamination, but more importantly, it will increase greenhouse gas emissions which will accelerate global warming.

The bizarre aspect to this story is that somehow lower oil prices is supposed to be a good thing for the oil industry. Predicting oil prices is not an easy thing to do, and as a practical matter the U.S. is already producing oil at record levels, so “drill everywhere” may not mean much additional oil production. But if the campaign’s promise comes true, and oil prices do fall sharply, that is not likely to be good news for the industry.

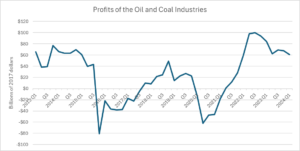

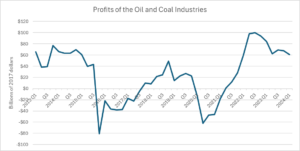

The figure below shows the combined profits for the oil and coal industry (the bulk of this oil) since 2013. The numbers are in 2017 dollars, so they are adjusted for inflation.

Source: NIPA Table 6.16D, Line 25.

As can be seen, profits fell from over $60 billion in 2014 to massive losses in 2016 and 2017. Profits recovered modestly in 2018 and 2019 but were still less than half the levels of 2014. The industry again took large losses with the pandemic shutdowns in 2020. Profits recovered in 2021, soaring to record highs in 2022 following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. In more recent quarters profits have fallen back to roughly their 2014 levels.

This pattern closely tracks oil prices. Oil was selling for over $100 a barrel at the start of 2014. Prices fell sharply in the second half of the year, bottoming out at $44 a barrel in the middle of 2015. After briefly leveling off, they plunged again at the end of the year, bottoming out at less than $30 a barrel in early 2016. Prices then edged up staying mostly over $60 a barrel until the pandemic hit.

The pandemic shutdowns sent prices to record lows. They then recovered with the economy, before soaring to peaks of more than $120 a barrel following the invasion of Ukraine. Prices have since fallen back to the $70-$80 a barrel range, which is comparable to pre-pandemic prices after adjusting for inflation.

Again, the future path of oil prices is not easy to predict, but there does seem a contradiction between the idea that allowing the industry to drill everywhere will both be a profits bonanza and also mean cheap gas for consumers. If a large increase in U.S. production does send oil prices sharply lower, the oil industry is not likely to be very happy.

The Trump campaign has made “drill everywhere” one of its main campaign slogans, implying that it will radically weaken environmental and other restrictions on oil drilling. This is supposed to be good for both the economy, since it would in principle mean lower gas and energy prices more generally, but also the oil industry since it won’t have to worry about government regulations in deciding where and how to drill. Increased oil production would be bad news for the environment since it likely means more local contamination, but more importantly, it will increase greenhouse gas emissions which will accelerate global warming.

The bizarre aspect to this story is that somehow lower oil prices is supposed to be a good thing for the oil industry. Predicting oil prices is not an easy thing to do, and as a practical matter the U.S. is already producing oil at record levels, so “drill everywhere” may not mean much additional oil production. But if the campaign’s promise comes true, and oil prices do fall sharply, that is not likely to be good news for the industry.

The figure below shows the combined profits for the oil and coal industry (the bulk of this oil) since 2013. The numbers are in 2017 dollars, so they are adjusted for inflation.

Source: NIPA Table 6.16D, Line 25.

As can be seen, profits fell from over $60 billion in 2014 to massive losses in 2016 and 2017. Profits recovered modestly in 2018 and 2019 but were still less than half the levels of 2014. The industry again took large losses with the pandemic shutdowns in 2020. Profits recovered in 2021, soaring to record highs in 2022 following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. In more recent quarters profits have fallen back to roughly their 2014 levels.

This pattern closely tracks oil prices. Oil was selling for over $100 a barrel at the start of 2014. Prices fell sharply in the second half of the year, bottoming out at $44 a barrel in the middle of 2015. After briefly leveling off, they plunged again at the end of the year, bottoming out at less than $30 a barrel in early 2016. Prices then edged up staying mostly over $60 a barrel until the pandemic hit.

The pandemic shutdowns sent prices to record lows. They then recovered with the economy, before soaring to peaks of more than $120 a barrel following the invasion of Ukraine. Prices have since fallen back to the $70-$80 a barrel range, which is comparable to pre-pandemic prices after adjusting for inflation.

Again, the future path of oil prices is not easy to predict, but there does seem a contradiction between the idea that allowing the industry to drill everywhere will both be a profits bonanza and also mean cheap gas for consumers. If a large increase in U.S. production does send oil prices sharply lower, the oil industry is not likely to be very happy.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión