April 30, 2015

The NYT has a column today by Uki Goni, warning of the bad things that will face Greece if it defaults. The default by Argentina in December of 2001 provides the basis for his warnings.

“Economic activity was paralyzed, supermarket prices soared and pharmaceutical companies withdrew their products as the peso lost three-quarters of its value against the dollar. With private medical insurance firms virtually bankrupt and the public health system on the brink of collapse, badly needed drugs for cancer, H.I.V. and heart conditions soon became scarce. Insulin for the country’s estimated 300,000 diabetics disappeared from drugstore shelves.

“With the economy in free fall, about half the country’s population was below the poverty line.”

There is no doubt that the people of Argentina suffered serious hardship due to the default. However it is important to recognize that they were suffering severe hardship even before the default. The economy contracted by 8.4 percent since its peak in 1998, and contracted by 4.4 percent in 2001 alone. The unemployment rate had risen to more than 19.0 percent. Even worse, there was no end in sight.

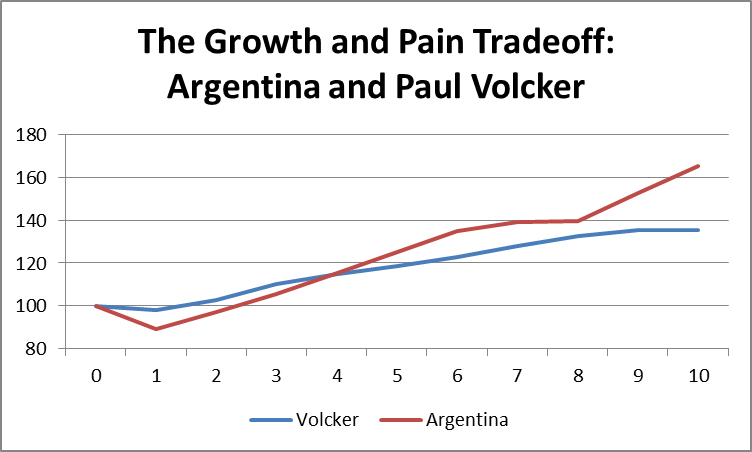

There is no doubt that 2002 was worse for the people of Argentina as a result of the default, but by the second half of the year the economy returned to growth and grew strongly for the next seven years. (There are serious issues about the accuracy of the Argentine data, but this is primarily a question for more recent years, not the initial recovery.) By the end of 2003 Argentina had made up all of the ground loss due to the default and was clearly far ahead of its stay the course path.

Source: International Monetary Fund.

This raises the question of whether the pain associated with the default was justified by the subsequent recovery. Clearly Mr. Goni thinks it is not. In this respect it is worth bringing in a hero among American policy wonks, Paul Volcker. Volcker is given enormous praise by economists (not me) for bringing on a recession in 1981 that brought inflation down from near double digit levels. This recession caused enormous pain of the sort described by Mr. Goni (people lost their houses and farms and couldn’t pay for necessary health care, unemployment rose to almost 11.0 percent), but the economy did bounce back in 1983. The vast majority of policy types think this pain was well worth it as a price to bring down inflation.

For further background, it is worth noting that the economy had been growing prior to Volcker’s decision to bring on a recession. Argentina’s economy was already contracting and virtually certain to continue to contract prior to the decision to default. In other words, there was no pain free path available to Argentina, whereas the U.S. economy likely would have continued to grow, albeit with higher inflation, without Volcker’s actions. (For cheap fun look at this paper showing the I.M.F. consistently over-projecting growth prior to default and then hugely under-projecting growth post default.)

Clearly Greece looks much more like Argentina than the United States in 1981. Its economy has already contracted by more than 20 percent, with unemployment now over 25 percent. And, there is little hope for improvement any time soon under the stay the course scenario. This should make the default route look more attractive, since the country has little to lose.

That doesn’t mean default will be pretty. People will suffer as a result, but at least default offers a better path forward. The striking takeaway from Goni’s piece is how the notion of short-term pain for long-term gain can be made to look so appalling in a case where it was almost certainly necessary, whereas a similar choice is widely applauded in the United States in a case where it almost certainly was not. (For any Brits reading this, plug in “Thatcher” for Volcker.) It would probably be rude to point out that the 1981-82 recession was associated with a sharp upward redistribution of income away from workers at the middle and bottom of the wage distribution.

Note: Typos fixed, thanks folks.

Comments