October 03, 2024

In August 2021, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) made its largest-ever allocation of Special Drawing Rights (SDRs) — $650 billion worth. Two months before the allocation took place, the G7 (comprising some of the world’s wealthiest countries, including the US), committed to rechanneling $100 billion of the SDRs they would receive to developing countries. Yet three years later, wealthy nations have effectively rechanneled only a tiny portion of their SDRs.

SDRs are an international reserve asset created by the IMF and allocated directly to member governments without any debt or conditions. They are convertible to hard currency, and are distributed according to the Fund’s quota system, which is why rich countries received almost two-thirds of the 2021 SDR allocation while low- and middle-income countries received only around 30 percent. However, it is low- and middle-income countries that have actually used their SDRs, and have done so predominantly, unlike rich countries that have no real use for SDRs. Yet, because of the differences in SDR usability, even this current lopsided distribution is actually progressive and favorable to low- and middle-income countries. The distribution asymmetry has led to the question: what if rich countries transferred their unusable SDRs to poor countries that could put them to good use?

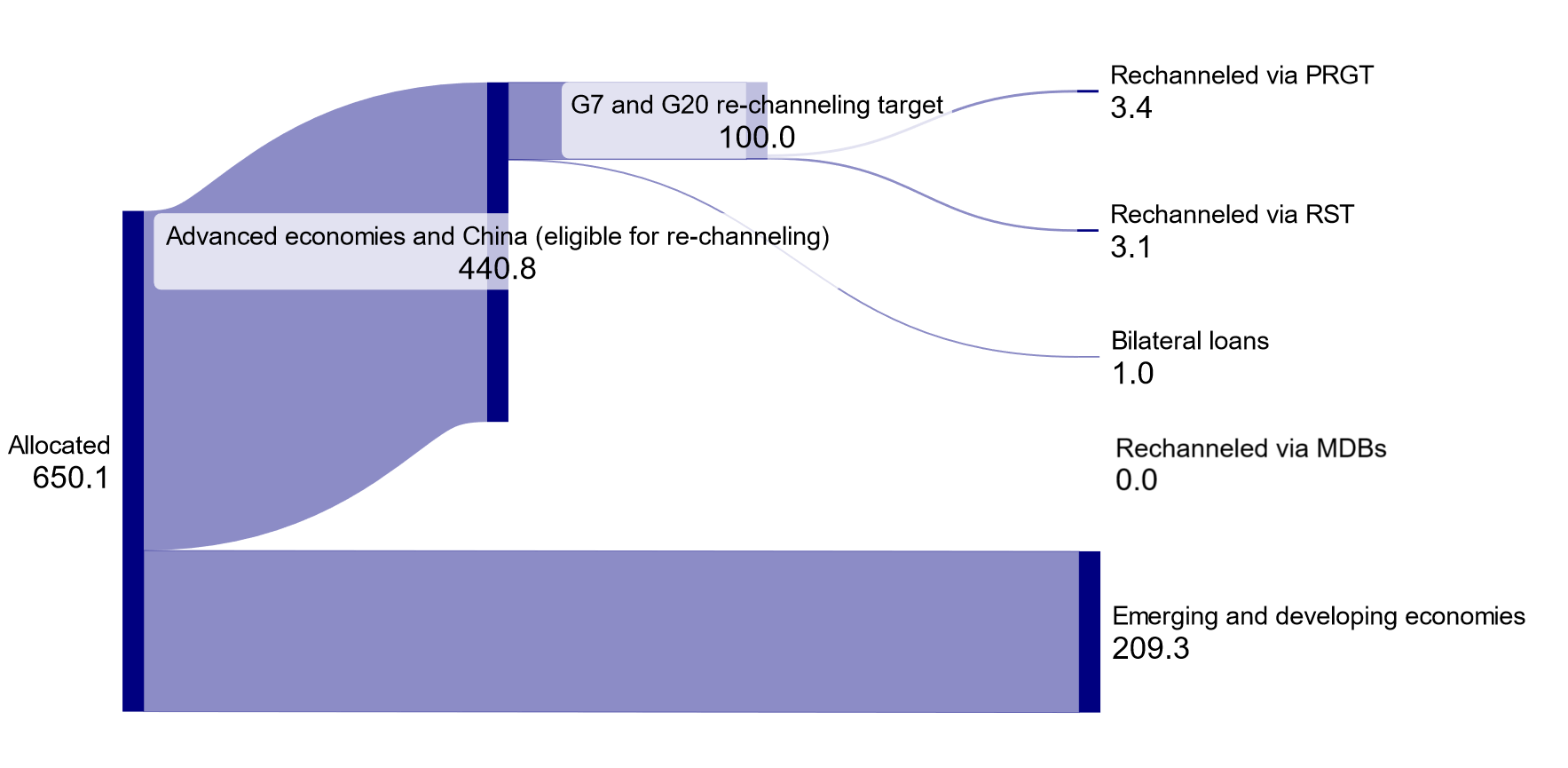

Despite rich countries’ grandiloquent pledges, only an estimated $6.5 billion in SDRs have been effectively rechanneled — see Figure 1 — through the IMF’s Resilience and Sustainability Trust (RST) and Poverty Reduction and Growth Trust (PRGT) facilities. These are loans with stringent and often harmful policy conditions attached. By contrast, the original $650 billion-worth SDR issuance in 2021 has proven to be over 30 times more effective in getting funds to developing countries than the IMF’s rechanneling efforts.

Figure 1: Effective SDR Rechanneling Compared to SDR Issuance in USD Billions as of September 23, 2024

Note: Effective rechanneling is actual disbursements of SDRs (and not other currencies) from the IMF trusts that increase countries’ SDR holdings in that same period. Source: updated reproduction from Vasic-Lalovic (2022).

“Rechanneling” has become a euphemism for more debt. However, it can signify both SDR donations and SDR loans. The potential for SDR donations is huge: just a quarter of rich countries’ unused SDRs can pay for the entire debt of what all — more than 90 — developing countries owe to the IMF. However, the IMF’s current statistical manuals on SDR accounting and its formula for the SDR interest rate make donations a nearly impossible feat. So far, no SDRs have been donated to countries, though in the last three years rich countries have granted $800 million in SDRs to subsidize the interest rate of the PRGT.

Given that bilateral SDR loans in the last three years amount to only $1 billion, the only significant available are loans through the IMF trusts or through designated multilateral development banks (MDBs). The largest MDB is the World Bank, and its president has said he’s “not signing on” to using SDRs. This leaves select regional development banks (RDBs) that have been pushing for (and were recently granted) an unnecessary IMF authorization for a hybrid capital proposal for SDR deposits. This was unnecessary because the RDBs were already SDR designated holders and their asset-liability treasury management and their solvency standards are up to the RDBs themselves. It would have been enough for the RDBs to adopt and adapt the RST’s treasury standards, as we proposed two years ago. Yet in the worst-case outcome, not only has the IMF board become a de facto financial regulator of RDBs, it has set an arbitrary ceiling for rechanneling through RDBs at 15 billion SDRs ($20 billion). This means that with encashment requirements, only $13 billion would be effectively disbursed to countries.

After three years, exactly zero SDRs have been effectively rechanneled to developing countries through RDBs. Even in the most optimistic scenario for rechanneling, a new issuance would provide 15 times as many SDRs to developing countries as this $13 billion. While lending through RDBs would have significantly less conditionality than the IMF’s RST, it would still result in more debt in the midst of a chronic debt crisis in the developing world.

But even worse, European Union countries have been forbidden from rechanneling SDRs through RDBs. Nor has the US Congress authorized any SDR rechanneling. The African Development Bank and the Inter-American Development Bank, the main proponents of the hybrid capital proposal, have to go in search of SDRs deposits from a few rich countries and — you guessed it — from other developing countries.

In addition to all this, given that rechanneling has, aside from exchange rate volatility, become a euphemism for more debt, it really doesn’t matter in what currency the loan is denominated. It is just more debt, and there is nothing special about using SDRs for conventional loans. Most damning is that for each rechanneled SDR, the investor country invests a previously existing asset and expects sufficient returns to at least cover its interest rate obligation to the IMF SDR department, i.e., currently about 4 percent. But rich countries like the US can instead lend in their own currencies — newly created liabilities — at any rate above zero. In other words, if the lending rate for a US loan is 5 percent with SDRs, the profit on the loan is 1 percent per annum, but if the loan is in US dollars, then the profit is 5 percent. This means that there is no incentive for rich countries, which usually lend in their own currencies, to engage in lending SDRs. If this is what rechanneling looks like, then rechanneling is dead.

The international community should get its priorities straight: when it comes to SDRs, the focus should be on debt-free financial support, not more debt. In terms of rechanneling, reform efforts should be centered on fine-tuning the legal, economic, and accounting policies so that SDR donations can take place. But under the current rules of the game, it is undeniable that the most obvious path forward, in terms of relief for developing countries, would be a new issuance of SDRs.